If you spend as much time as I do crawling around the internet arguing with extremists, you quickly learn the “that source is biased” move. You present a piece of evidence, and the person won’t even look at it because, they say, that source is biased.

Let’s start with that isn’t what you do with a biased source. You don’t reject it; you look at it skeptically–you check its sources. Right now, a lot of people are refusing to look at claims that Trump hasn’t been as successful as he claims because, they say, that argument is from the Hillary camp. That’s called the genetic fallacy–it doesn’t matter where the claim originated; it matters if it’s true. Whether it originated with Hillary camp or not, it’s possible to check whether they are using Trump’s numbers about his own wealth. If they are, it’s a claim to take seriously.

But, for a lot of people, that isn’t how it works. They believe that you can reject anything said by what social psychologists call the “outgroup.” The basic premise is that the “ingroup” is “objective” and the “outgroup” is “biased,” so, to determine if someone is “objective,” you just ask yourself if they’re in the in or outgroup.

Let me explain a little about in and outgroups. An ingroup isn’t necessarily powerful—it’s the group you’re in. So, if someone asked you to talk about yourself, you would describe yourself in terms of various group memberships—you’re a Pastafarian, Sooner, essentialist feminist, neoliberal, knitter. Social psychologists call that group (the one you’re in) the “ingroup” and various groups you’re not in (it’s important to your self of identity that you’re not like Them) “outgroups.”

We all have a lot of ingroups, and we have a lot of outgroups, and the importance of any given one can heighten or lower depending on the situation. We are made aware of those many (even contradictory) group memberships when they’re under threat, unusual, or interesting. If you are an American, and you find yourself in a space where American is an outgroup, you’ll likely bond with other Americans. Sitting in a group of people in a classroom in Tilden, Texas, if asked to say something about yourself, you wouldn’t say, “I’m an American.” Sitting in a group of people in a classroom of mixed national origin in Belgium, you’d be pretty likely to say, “I’m an American.” If, in Tilden, another American said something critical about Americans, you’d be more likely to listen than if a non-American said it in Belgium. If you’re already feeling a little marginalized for your group membership, you’re more likely to be at least a little defensive.

And here is a funny thing about ingroup membership. There is a kind of circular relationship between your sense of your self and your sense of the ingroup—you think of yourself as good partially because you see yourself as a member of a group you think is good, and you think that group is good partially because you think it’s made up of people like you, and you think you’re good. Your group is good because you’re a good person, and you’re a good person because your group is good.

Because you’re good, and because your group is good, then you and other ingroup members necessarily have good motives. Duh.

Thus, we have a tendency to attribute good motives to members of the ingroup, and bad motives to members of the outgroup, for exactly the same behavior. An ingroup member who works long hours in order to make a lot of money is a hard worker; an outgroup member who does that is greedy. An ingroup member who gives a lot of advantages to family members is loyal; an outgroup member who does that is motivated by prejudice against outsiders. An ingroup member who says something untrue is mistaken; an outgroup member is deliberately lying. Politicians we like are motivated by a desire to benefit their community or country; politicians we don’t like are driven by a lust for power.

An example I use in teaching a lot is how we respond to a driver in a car with a lot of bumper stickers who cuts us off on the road. If the bumper stickers suggest the person is a member of an ingroup important to us—we like the politician they endorse, for instance—we’re likely to find excuses for what they’re doing. We might think to ourselves that they’re running late, or didn’t see us, or perhaps (as I once thought to myself) it’s actually an outgroup member who borrowed a car. If the bumper stickers show it’s someone we think of as an outgroup, we’ll think, “Typical.”

In other words, we rationalize or explain away bad behavior on the part of ingroup members as a temporary aberration, an accident, or something caused by external circumstances. But, bad behavior on the part of someone in an outgroup is proof that they are all like that—it’s an example of how they are essentially bad people.

If a member of the ingroup behaves well, then we say it’s the consequence of internal qualities—their essence. If the driver with all those bumper stickers we like does something really nice, we’ll think, “Typical.” It’s proof that ingroup members are essentially good people. If a member of the outgroup behaves well, then we say it was done for bad reasons, or done by accident.

So, if an ingroup political figure kicks a puppy, she was mistaken, or meant well, the puppy deserved it, or we might even try to find ways to say it wasn’t really kicking. If an outgroup political figure kicks a puppy, it’s proof that he is evil and hateful and that’s what they’re all like.

If an outgroup political figure saves a drowning puppy, she just did it get votes. If an ingroup political figure does it, that incident is proof that people like us are just plain better.

We are more likely to empathize (or, in rhetorical terms, identify) with people who persuade us they’re members of an ingroup important to us. We’re more likely to be persuaded by them—that’s why salespeople immediately try to find some point of shared identification. They’ll also often try to bond by claiming to share an outgroup—rhetoricians call this “identification through division.” That is, the salesperson tries to get you to identify with her by sharing your dislike of “them.”

In Texas, where I live, there is a notorious rivalry between Texas A&M (the “Aggies”) and University of Texas (the “Longhorns”). My husband went to A&M, and wears an “Aggie” ring. When we go shopping for big-ticket items, the salespeople will often notice his ring and start talking trash about Longhorns, and how awful the University of Texas is. They’re trying to bond with us by showing that they share the Longhorns as an outgroup. Since I’m a professor at UT, it doesn’t generally go over very well.

If I get you to identify with me, to see yourself as like me in some important way, I’ve persuaded you that you and I are in the same ingroup. If I’m really successful, I get you to identify with me so much that you will perceive an attack on me as an attack on you. I now have your ego attached to my success. That’s an important part of demagoguery (but not every time someone does that is demagoguery—it’s a part, but not the whole).

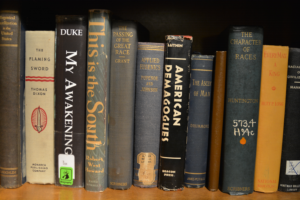

One of the main goals of demagoguery is to persuade people not to listen to the outgroup (basically because the claims of the ingroup would fall apart if people looked at them critically). And it does so by saying, “They are biased; we are objective.”

But, again, you don’t reject a biased source; you look at it more carefully. Whether claims about his wife’s immigration status, his wealth, the lawsuits against him, his hiring of illegal immigrants, his screwing over little people, his poor financial record, his lying originated with the Clinton camp doesn’t matter–what matters is whether they’re true. And that can be determined by drilling deep into the sources of those “biased” sources. That is how you assess evidence.