I am hopeful about the last week, and that might seem odd.

Train wrecks in public deliberation happen when political issues become factional ones, so that decisions are weighed entirely in terms of whether the ingroup or outgroup wins. And decisions that hurt the outgroup, even if they hurt the ingroup more, are seen as wins. In those moments, it’s common for some narcissist to arise and become the object of a charismatic leadership relationship.

Under those circumstances, the leader’s claims about policies are irrelevant—all that matters are his (almost always) performances of decisive leadership. It doesn’t matter whether his decisions turn out to be right—what matters is that they were decisive. In these circumstances, rejecting expert advice, refusing to take time to come to a decision, refusing to listen to anyone who disagrees, turning away from disconfirming evidence—all those things contribute to the sense that the leader is decisive, and therefore good.

Of course, as far as actual evidence about that kind of leadership, it’s a disaster. (https://hbr.org/2012/11/the-dark-side-of-charisma) Stalin, Hitler, Pol Pot, Mussolini—all got their power from charismatic leadership. Not all people who draw power from the charismatic leadership are disasters for their countries (or regions) but everyone who only draws power from charismatic leadership is.

Here’s the difference. Every effective leader in the media-dominated world must be charismatic. But having charisma, and drawing power exclusively from charismatic leadership are not points on a continuum—they are orthogonal (despite what writing on leadership says). A charismatic leader is one who’s power comes entirely from his (again, almost always his) presenting himself as supernaturally wise and powerful and therefore above the normal standards of fairness, consistency, or reason. The charismatic leader being inconsistent, being unable to give reasons, violating all promises—all those things increase his power.

So, how do you know if a charismatic leader is following bad policies? You don’t. You can’t. That he appears to be following risky and unwise policies enhances his positions as a charismatic leader, and calls on you to demonstrate your commitment to him by continuing to believe him despite his engaging in policies all the experts say is wrong, that contradict what he said he’d do, and that might seem ill-considered. You must like that he is playing from the gut.

Once someone has entered in the charismatic leadership relationship, there is no way to admit that he is a shitty leader without your admitting that you’re a shitty judge of character. Charismatic leadership is inherently toxic in that it connects the followers sense of self-worth to the possibly arbitrary policy agenda of the person they have decided really represents them.

In really nasty situations—ones in which demagoguery has become the norm for political discourse–, than all the ambitious political figures try to enact charismatic leadership. Anyone who doesn’t is seen as not “Presidential” (aka, media coverage of the 2016 Presidential election). One problem we have to admit is that the dominant media love themselves some charismatic leadership—it’s great for ratings.

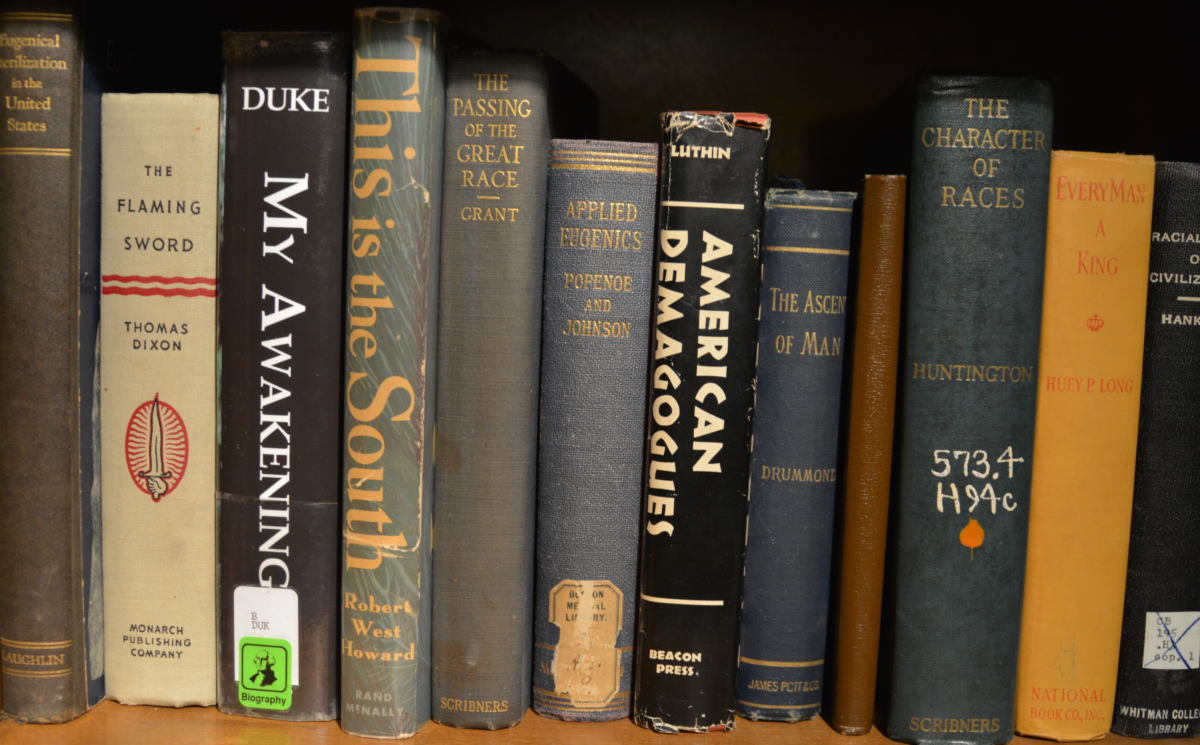

Communities in which charismatic leadership is the dominant relationship between voters and a leader don’t generally end well. They usually end up in an unnecessary war (the Sicilian Expedition, Napoleonic wars, or WWII) if there is a single leader who is mastering all the available energy. If it’s a situation with a lot of rhetors drawing power from the charismatic leadership relationship you might have tremendous cultural commitment to an obviously unwise policy (the US commitment to slavery and, later, segregation, or current homophobic policies).

Trump is in the former category. He is not a person to give up power, and he doesn’t play well with others (and that’s what his base likes about him). He has already shown that he will enact policies that harm his base, and they have shown they don’t care. This isn’t about some kind of rational commitment on their part to his policy agenda. You can tell that because, if you ask them, they say, BUT THE DEMS DID SOMETHING. This isn’t about policies—this is about being on the winning side.

That’s an interestingly irrational argument. Let’s say that the question is whether Trump fired Comey because Comey was pursuing Trump’s reliance on Russia’s having interfered with the election. True believers will say, THIS DEM FIRED SOMEONE. That’s completely irrelevant. It doesn’t matter if Clinton or Obama engaged in human sacrifice at every full moon and therefore fired someone. For Trump true believers, the question (every question) is an opportunity to prove that Trump is better than others, and so any bad (even if irrelevant) action on the part of THEM is proof that he is good.

And so they don’t see that doesn’t answer the question at all. Clinton might have kicked puppies and fired someone, and that’s actually irrelevant to whether Trump fired Comey because Comey was going to expose Trump’s reliance on Russia having interfered with the election. Both could be true.

In a charismatic leadership relationship, the followers don’t care if their leader did something bad; they only care whether (in some weird calculus in their minds) their leader can be positioned as better than the other.

And that’s how charismatic leaders screw over their followers. And they always do. Trump has done it faster than most, and his followers have shown themselves to be the most charismatic followers ever since they haven’t balked. He said he would release his returns, and didn’t. He said he would jail Hillary, and he didn’t. He said Obama’s birth certificate was an issue, and then he said it wasn’t. He said he would rid the government of lobbyists, and he filled his administration with them. He said he would end corruption, and he and his family are explicitly using his position to profit them more. He said he didn’t fire Comey because of Russia, and he said he did.

And his base stands by him.

They were thrown under the bus long ago, and there is no circumstance under which they will admit that. And you know that because, those of you with them in your FB feed know that they don’t even try to defend him. They say, BUT THE DEMS….

And they can’t defend what he’s done in terms of what he said he’d do, or what they said he’d do. They can’t only say his team is better than that team.

So, how do we get out of it?

Unhappily, one way is war. The charismatic leader (again, not the leader who is charismatic, but the leader whose power comes entirely from the charismatic relationship) leads people into a stupid war (and, given enough power, they always do) and it’s a disaster (because leaders who depend entirely on charismatic leadership are disastrous in war). The war is a disaster, and many people (not all) decide that was bad. Unfortunately, they generally either say the leader wasn’t wrong, or they pretend they never supported the guy in the first place.

Another is that the leader is representing a minority group, and gets shut down by the legal or traditional authorities (the other two sources of power that Weber identified). That’s what happened with the various rhetors who tried to play charistmatic leadership on behalf of white supremacy in the US South. The Supreme Court shut them down.

We have a Supreme Court that has a majority that is fine with authoritarianism, so that will not play well for democracy.

One of the premises of charismatic leadership is that normal rules of fairness don’t apply. The narrative is that the ingroup has been SO victimized by all these fairness rules, or innovation has been SO hampered by all these rules about how to treat labor, not being able to destroy the environment, you can’t scam investors, and “political correctness” that means you can’t just buy your way into the policies you want! The whole notion that balancing innovation and fairness might involve complicated compromises can be rejected in favor of all the decisions being thrown into the lap of the charismatic leader whose judgment will instantly solve the dilemma. In other words, decisions are complicated—a good leader sees the instantly obvious answer. (Notice that Trump has backtracked even on this, without any fallout from his base.)

Short of a disastrous war that shows the leader wrong (and even that doesn’t always workd), the best way to undercut charismatic leadership is for ingroup rhetors to condemn the leader on procedural or policy grounds. That is, while outgroup rhetors should condemn the leader, it won’t work for too long because one of the first acts of the charismatic leader is to shut down or marginalize that criticism—ingroup members never hear it.

Trump has Fox and the GOP Noise Machine on his side. And the major argument that those sources make is that their listeners shouldn’t listen to any potentially disconfirming information. And you know how well it works. You all have friends or family members who repeat talking points from biased sources but who won’t look at anything that might disagree with them on the grounds that those sources must be biased.

They don’t care about biased sources—that’s all they listen to, read, or watch. The like biased sources.

They only object to sources that might complicate their biases. That’s important to note, as people can start to flip when they realize that they’re being suckered. And Fox suckers them. If Fox really were telling them the truth, then there’d be no harm in looking at other information. The more that Fox tries to tell people not to look at other sources, the more it’s acknowledging its version of the “truth” can’t withstand actual analysis of evidence.

Fox isn’t conservative. It has no coherent political philosophy other than being GOP (which, like the Dems, has flopped all over the place on policy). There are conservatives, and they’re beginning to fall away from Trump, and that gives me hope.

Oddly enough, what also gives me hope is that Trump is overplaying his hand. What sometimes undoes a charismatic leader is that his own belief in himself means that he doesn’t really believe he can permanently alienate any group, and so he just does whatever he wants thinking he can charm or bluff people back into his entourage regardless of his having screwed them over.

So, there are two hopeful signs in the last week. First, Trump has a problem is that many of the people on whom he relies hate him, and feel used by him. (https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/12/us/politics/trump-sean-spicer-sarah-huckabee-sanders.html?smid=pl-share)

And that number seems to be increasing. Trump, for all his ability to generate extraordinary public loyalty, doesn’t seem to have much ability to generate personal loyalty, and he never has.

That makes the actively bizarre relationship of him and his First Lady interesting. There has never been a First Lady who has signalled so much animosity toward her husband, and he has only one daughter who can manage to show public affection to him. It doesn’t matter because it shows he’s a bad person or blah blah blah. It matters because it shows that Trump, who will thrown anyone under the bus, has managed to gather around him people with his same ethics. That’s a good thing for democracy. When the time comes that it looks as though spilling the beans on him is a good choice, there will be many people willing to do it.

The second hopeful sign is that outlets like The Economist, Forbes, and Wall Street Journal are publishing scathing articles about his incompetence. Neoliberal free-market fetishists will put up with anything other than random incompetence. (They’ll even tolerate strategic incompetence, such as the Bush Administration.)

But here is one more unhappy point. What does in people like Trump is overreach. And so, at best, we have months of his continuing to behave badly, the GOP Propaganda Machine spinning it as fine, and the most of the GOP political figures selling their soul to Trump penny by penny. And they will try to consolidate their power (as every authoritarian government does) through voter suppression.

So, this is all about 2018, and every reasonable person voting against any figure who has supported Trump.