[The introduction to this argument is here.]

Many people look back at Hitler and believe someone like him could never sucker them because, they believe, he pounded on a podium shouting for the extermination of Jews on the basis of what everyone could recognize as rabid and irrational racism. They recognize that Hitler relied on charismatic leadership, but they think they’re immune to it.

Hitler didn’t begin by arguing for extermination of the Jews. He told his audience that Germany, which should be great, was in a state of political, economic, and moral collapse because it was weakened by the presence of those people. He said we’re weakened by disagreement, and the disagreement is purely the consequence of them. He said the solutions to the major problems of the era were simple, and he could (and would) enact them immediately. Germany was trapped by procedural quibbling, “parliamentarianism” (by which he meant that everything had to be argued in the equivalent of Congress), liberals who just want to slow everything down, experts who try to tell people like you and me that our beliefs are wrong, Marxists who want to destroy what we have, and Jews who are all terrorists.

Weimar Germany was (like most of Europe) profoundly antisemitic, ranging from “they’re okay as neighbors, but I wouldn’t want my daughter to marry one” through “it sure would be nice if they all went away” to “we should kill them all.” That last group wasn’t especially large, but the other versions were widespread. (And, as history would show, the “milder” ones could be morphed into exterminationist.) The Jewish stereotype (in literature, film cartoons, even songs) was that Jews were clubby, greedy, crude, and damned to Hell. Sometimes that stereotype was presented as though it were positive (G.K. Chesterton’s antisemitism fits into this category, and Wyndham Lewis’ Are Jews Human is another apt example).

Many people decide that a claim must be true if it’s repeated in their informational world a lot, if it’s repeated by people they respect, unanimously supported by their in-group, and especially if it’s contested by one of their out-groups. This process is sometimes called “social knowing” (you know something because it’s taken as a given in your social group). Basically, this whole long discussion of Hitler could be compressed in my saying that approaching decisions purely through social knowing is what enabled Hitler (and Stalin), and so anyone who approaches decisions that way doesn’t get to pretend s/he would have recognized Hitler or Stalin as evil. Nope. Congratulations: if you reason that way about politics, here is your death’s head symbol!

Karl Marx was Jewish, and many of the people in Lenin’s close circle were Jewish, and almost all of the Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda equated being Jewish and being Bolshevik. Thus, and this is important to remember, the Nazis presented their policies of exclusion and disenfranchisement (and, eventually, extermination) as politically necessary–this wasn’t religious bigotry, but a necessary response to the terrorism that necessarily came about if Jews were part of the community.

Of course, most Jews weren’t Bolshevik, and not all Bolsheviks were Jews, but people engage in very sloppy reasoning when it comes to an out-group. Since we have a tendency to assume the out-group is essentially evil, then the bad behavior of some of them seems to typify all of them. By the early twentieth century most of the major financiers were not Jewish, but the Rothschild family came to be the symbol of international finance.

Thus, a large number of people were willing to blame Jews for Bolshevism, capitalism, the loss of WWI, entry into WWI, and anything else that needed a scapegoat. Sometimes that stereotype was presented by an author as though it wasn’t unreasonable—a hero or narrator might grant that not all Jews were involved in a worldwide conspiracy, but assert that all conspiracies were Jewish (an assumption so widespread that it amounted to a cliche in thrillers). A fair number of people also blamed Jews for draining blood from Christian boys, killing Jesus (a particularly pernicious claim), stealing consecrated hosts. Many people, especially those who had made it through the near Soviet-style revolts in some German cities, were deeply opposed to Soviet-style communism (a not unreasonable concern) but a lot of anti-communist propaganda equated Bolshevism (as it was called) and Jews. It’s important to understand that connection, otherwise it’s easy to miss why Nazism was so successful.

Jews were thoroughly marginalized in Czarist Russia, and, so, compared to the number of Jews in the general population, it could be argued that there was a disproportionate number of Jews in Lenin’s immediate circle. But he also had a disproportionate number of close advisors from Georgia, and no one wonders about the disproportionate number of New Yorkers in the official and unofficial cabinet of a New York President. We expect that people will rely heavily and work with people in their social circle; it’s only if that circle is marked by out-group membership (especially by race or religion) then we decide there is a causal correlation. Since Jews were marked as out-group, then the Jewishness of any participant in Lenin’s revolution or cabinet was marked and assumed to have some kind of causal relationship to Bolshevism. (That most supporters of Lenin were not Jewish is ignored.)

Here’s one way to think about that. If a person wearing a t-shirt showing they support a politician, religion, or sports team you loathe treats you badly in line at the grocery store, you’ll attribute their being a jerk to their being in your out-group. They did that jerky thing because they’re Wisconsin Synod Lutherans, and we all know how they are. That incident will confirm your sense that Wisconsin Synod Lutherans are inherently evil. If someone behaved exactly the same way but had a t-short that showed they shared some kind of identity important to you, if you are Wisconsin Synod Lutheran for instance, then you would attribute their behavior to something else (they’re wearing someone else’s shirt, they’re having a bad day). Unhappily, therefore, a depressing number of people who self-identified as Christian equated “Jewish” with “atheist Bolshevism” (the same way that many people now equate “Muslim” with “politically motivated terrorists”).

Thus, in Weimar Germany, many people were willing to believe that Bolshevism was Jewish, and while people were willing to grant that not all Jews were Bolshevists, they believed that enough of them were that the entire “race” (and keep in mind, Judaism isn’t a race) should be removed from Germany. It was the peanut analogy—if you know that some peanuts are poison, you would throw out the whole bowl, or at least keep more from entering.

Let’s be clear: the attempt to “cleanse” Europe of all sorts of identities (Jews, Romas, Sintis, Poles, intellectuals, Marxists, union leaders, liberals, homosexuals) began as an argument that was framed as “it’s best for all of us if they go elsewhere.”

Hitler’s policies regarding stigmatized groups could be framed as reasonable throughout his career because he would appear to have been just on the edge of acceptable racist discourse. He would have appeared crude to a lot of people, but also a lot of of his followers would have found his “honesty” on “what they all knew” to be refreshing. And he didn’t immediately call for extermination; he called for refusing to allow more immigrants. Initially, his claim was that Germany needed to protect itself against parasites (takers), immigrants, peoples not capable of being really German, groups that were inherently criminal, his political opponents, and that meant more purity in the culture, more rigid actions on the part of police, less concern about due process and fairness, and a more open equation of German-ness and a particular political group.

Hitler persuaded a large number of people that he was them, that he cared about them, and they needed to throw all their faith onto him, and he persuaded others (who were appalled at the liberalism of Weimar Germany) that he was their only choice to undo the liberal policies of Weimar politics. Many people voted for him for those reasons, even ones really uncomfortable with his tendency to engage in bigoted claims about various races and religions. They believed that democracy was dead, as was shown by the inability of the Weimar democracy to make the situation better (it actually had done a pretty good job, but the main problem was that compromise and deliberation were demonized, but that’s a tangent I’ll avoid).

My point is that Hitler’s genocidal policies wouldn’t have seemed to his audience as purely racial; it would have seemed to his audience as though the groups he was targeting really were political and economic threats. A lot of people really did believe that Jews were intent on imposing communism everywhere and they could name acts of terrorism and revolution in which Jews participated, and they could point to all sorts of media, common discourse, and “walking down the street” experience to say that some groups are just useless takers—Polack jokes, getting “gypped” by someone.

There were terrorists who were Jewish; there were criminals who were Sintis. Therefore, “normal” people could “know” that a group of Jews or Romas would include terrorists and criminals, and so they defined the essence of Jews and Romas as terrorist and criminal. Germany had a lot of terroristic violence, with a lot of it (most?) committed by Nazis and other volkisch groups. But many people wrote off that violence as either justified (as self-defense against the Jews) or inessential. The US, right now, has a lot of terrorism, most of it committed by white males who self-identify as Christian. Yet, how many people worried about terrorism are worried about white male Christians? They engage in the no true Scotsman defense, and only worry about out-group violence, and, as too many people in Weimar Germany did, they are willing to generalize about the essence of another religion, while engaging in considerable cognitive work to keep from admitting that most terrorism is in-group.

I’m not saying that the Jews of the 1917-1933 are just like Muslims of 1996-now. I’m not making a claim about facts; I’m making a claim about how people in a moment understand things. And how they understand things largely depend on the media they consume. In Weimar Germany, a time of highly factionalized media, people were really worried because of events that had actually happened (the communist uprisings), but also ones that hadn’t (desecrations of the host, Jews having killed Jesus, but they decided those events were the consequence of identity (Jews) and not policy (the German commitment to winning WWI) or process (that there was no way for the country as a whole to get good information about the war or influence decision-making). Weimar Germany media was, all at the same time, rabidly factionalized (if you read this newspaper, you only heard about terrible things they did and never about terrible things your group did), agreed that the mistakes of WWI wouldn’t be usefully debated (but just factionalized), and agreed that significant dissent is unpatriotic.

Hitler accepted a narrative about civilization and race that was popular in some circles and also accepted among many experts (especially the new science of genetics). The idea was that evolution is progressive, so that a “more evolved” species is better in every way than a less evolved one (Gould’s Mismeasure of Man remains a really good introduction to all that discourse, even with some disagreements as to his argument on brain size measurements). In this view, “immorality” is more common among “lower” species, so that higher animals (like humans) behave in a more moral way than lower animals (like apes). In addition, dominant genetics said that there were sometimes “throwbacks” in evolution (called atavism), so that humans are sometimes born with characteristics genetically connected to earlier (and lower) stages in our evolution, such as babies born with tails. Races, many of these people argued, functioned as species, and so there are races that are closer to animals, and they are more inherently criminal, and essentially incapable of autonomy. This version of genetics was simultaneously deeply flawed and very popular. And it’s important to understand both parts to understand Hitler’s popularity.

Since morality is just as much genetic as a tail, this argument ran, and the more genetically advanced are more moral, then immorality is also an evolutionary throwback. Groups that are more immoral are more like animals in every way, and it’s because of their genetics.

The last bad idea in this cornucopia of bad ideas is that we should think about human genetics the way we think about breeding racehorses, bunnies, or chickens. Notice that throughout this discussion I haven’t defined “morality,” nor terms like “higher” or “better.” Here I’m following how geneticists wrote–they began their research by assuming that there was perfect agreement on those terms, and thereby enabled themselves not to see the circularity in their arguments. Most people charged with crimes were recent immigrants or criminalized ethnicities, and, since crime is immoral, they concluded that those ethnicities were genetically criminal. (We still make this mistake, by assuming that rates of arrest are perfect representations of rates of commission of crime.)

So, what they didn’t notice in their own research was that their own standards of “better” were actually pretty odd. They tended to equate, without noticing, market value with better. A racehorse is “better” than a drafthorse insofar as you pay more for the former than the latter, but a racehorse is a terrible draft horse. To get the fastest horse, breeding two fast horses is a good choice, but a fast horse is not always the better horse. The research on chickens and bunnies is unintentionally hilarious (with horror about the monstrosity of a bunny with one ear upright and the other floppy). It’s also contradictory, since, as mentioned above, market value was often taken as a pure measure of goodness, and market value is often enhanced by genetic oddities. Or, in other words, purebred, and inbred are pretty similar, as shown in the Hapsburg Jaw. I love Great Danes, and even I will admit that a purebred Great Dane is not a better dog than a mutt–it’s much more likely to have terrible problems. But early twentieth-century genetics assumed that purity is always better, except when it didn’t.

What’s odd to a rhetorician about the genetics rhetoric is that it was so obviously wrong, even in its era. Anthropologists, linguists, and even a lot of biologists took issue with geneticists’ arguments in the first decade of the 20th century (that’s why geneticists had to form their own organizations–they couldn’t stand the critiques). Anyone familiar with the Habsburgs knew purity wasn’t good, and genetics simultaneously assumed that purity was better AND condemned inbreeds like the Jukes family.

Early twentieth century genetics was just a muck of contradictory assumptions. For instance, it was a convention to say that a cross between a higher and lower was halfway between the two, but, of course, even royal families had their “lower” babies–epileptics, hemophiliacs, homosexuals. And anyone even a little familiar with breeding dogs or horses knew that not only did you often get a dud from two great individuals, but that there were always surprises from less than stellar lines. That it was muddled is an important point, because when a particular sustained conversation (that is, a bunch of people who have created a kind of argumentative ingroup—a subreddit, Fox News, DailyKos, analytic philosophers, native plant gardeners—sometimes called a “discourse community”) have an argument that doesn’t have internally consistent arguments, then you know you’ve got an ideologically-driven discourse community.

That point might seem a little pedantic, and it’s important for understanding when the Hitler analogy is and isn’t relevant, so I should explain it a little more. In rhetoric, it’s common to talk about enclaves, which are little safe spaces in which like-minded people can huddle together and do nothing but agree how awesome they all are.

Enclaves are great, and we all need them, and so every life should have at least one. Enclaves are places where we all agree, and we go to feel that we are part of a group that is entirely right, and entirely good, and entirely powerful.

Enclaves are useful for motivation, and, really, it’s just lovely to be in an enclave. Everything is clear, and everything is comfortable and no one will tell you that you might have fucked up.

Enclaves can be politically important. Lefty women relegated to making coffee and working the mimeograph literally got together and discovered they all shared similar experiences. Our Bodies, Our Selves came out of an enclave. The Tea Party is an enclave-based movement, as was Earth First. Within your enclave, deciding that loyalty to that group is important makes perfect sense. The institutional goal of an enclave is to make people feel safe within a group. Enclaves are also good for motivation—before putting on a show, or playing a competitive sport, and in those circumstances it wouldn’t be helpful for someone to say, “Well, maybe the other team is better, and really should win.”

But all the research on decision-making is clear that it isn’t good for a large institution or community to make decisions from within an enclave, largely because of that enclave emphasis on loyalty to the group being such a high value. Good decisions require good disagreement, and criticism of the in-group is generally perceived as disloyalty. And, so, while it’s common for political agenda to be brainstormed within an enclave, and it’s healthy for all of us to retreat to one from time to time, political agenda should be subject to criticism, worst-case scenario thinking, assessment of weaknesses and challenges, and honest assessments of previous failures. So, at some point, that political agenda needs to be shared outside of an enclave.

Determining processes and policies within an enclave is challenging, because of the value on loyalty, and so it’s common for enclaves either to splinter into sub-communities on which everyone agrees, or to begin threatening dissenters with violence and exclusion. Unhappily, the more that an enclave values loyalty, the more likely it is to devolve into smaller communities, or become a community in which people can’t disagree.

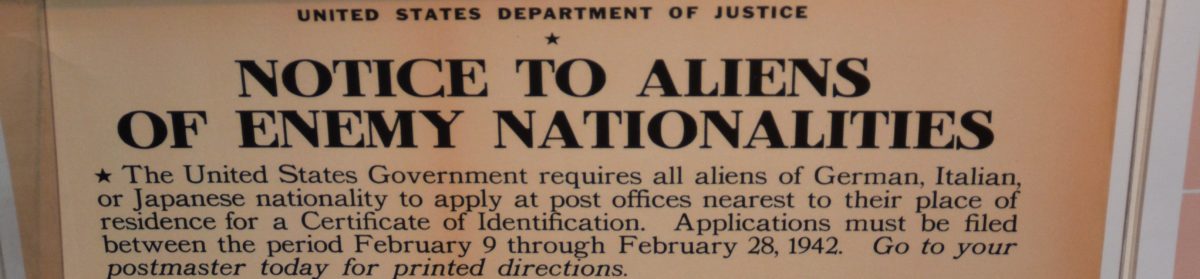

Genetics ended up being an enclave expert discourse. Instead of respond to the serious objections and criticism of eugenics made by contemporaries, they created their own journals and departments (and as in the case of Franz Boas, tried to get really threatening critics fired). And what eugenics had to say could be defended with complicated charts and statistics (which was a relatively new field at that point), and it confirmed everyday and very popular racism. But it was popular, and it was powerful–even college textbooks endorsed it. That science was used to rationalize the US forced sterilization of 60k people, the extraordinarily restrictive 1924 Immigration Act, Japanese internment, anti-Asian immigration/naturalization rules and statutes, antimiscegenation laws, and segregation in the US. Every claim of that kind of genetics was rejected by methodologically sound research in anthropology, linguistics, and biology, but my point is that it was easy for racists to find apparently expert support for their racist policies (see Science for Segregation).

The most problematic claims of eugenics were that “race” is a biological category (the history of debates over “whiteness” show that isn’t true); that races exist on a hierarchy of civilization (some races are essentially more gifted with intelligence, morality, strength, and all the virtues that merit higher status and pay–other races are given the virtues, such as being good with children, that are connected to lower status and pay); that the “mixing” of races results in children who are closer to the “lower” than the “higher” race; and that the “white” race (sometimes Nordic, sometimes Aryan) is responsible for all the great civilizations in the history of humanity, and those civilizations fail when the white/Nordic/Aryan race stops being pure. Race-mixing, these people say, weaken civilizations. Hitler used this narrative to argue that “lesser” races had to be exterminated, and that punishing ‘race-mixing’ with death was justified. Even after the war, supporters of segregation cited the same shitty “science” that justified Hitler’s genocide–that line of argument figured into the lower courts’ rulings on Loving v. Virginia in the 60s.

So, while we look back at Hitler’s racism and see it as insane, and while the most methodologically sound scholarship of the era had long since shown it to be ideologically driven, people who wanted to believe that some racial groups were inherently more dangerous, more criminal, more prone to terrorism, more genetically driven to be poor could find experts who would tell them that they were right. Hell, they could find entire departments at some universities who would tell them that.

What made Hitler’s “science” bad wasn’t that it now looks bad to us, nor that it was a fringe science, nor that it didn’t have supporting evidence—it did. What made it bad was the logic of their arguments—their failure to define terms, to put forward internally consistent arguments, and to define the conditions that would falsify their claims. For instance, eugenicists never came up with a definition of “race” that they used consistently—sometimes they meant nationality, sometimes language group, sometimes, as in the case of “the Jews,” they talked about a religion as though it were a race (the same thing is happening now with people who refer to the “Muslim race” or who assume that “Muslim” and “Arabic” are the same).

In Germany, the “science” was slightly different, as was the religious rhetoric. In the US, there was a lot of support for “science” that said that African Americans, Latinx, Native Americans, and Asians deserved their economic, political, and cultural situation because it was the natural situation. In Germany, there wasn’t as much political need to rationalize the oppression of African Americans, Latinx, Native Americans, or Asians, but Jews, Sintis, Romas, various central and eastern European groups filled that same role, and there was the same rhetorical need to naturalize their oppression. Hitler’s long-term plan was to establish the same kind of plantation system in eastern Europe that England had in places like Rhodesia (Kershaw’s biographies of Hitler are especially good on this).

Although he called himself national socialist (meaning not the international socialists–that is, Marxist socialism), what he meant was European colonialism. In his era “socialism” meant redistribution of wealth, and he imagined a racial redistribution of wealth. Central and eastern Europe would become the Rhodesia of Germany. So, once Europe was Jew-free, then the other lesser races would behave in the ways British colonialism used Africans. Poles, for instance, would act as workers, perhaps even managers, for the large estates run by Aryans.

Hitler’s plans were more extreme that most of the dominant rhetoric of the era (which was still pretty racist), and so he was clever about keeping it out of the larger public sphere. But he meant it, as is shown by his deliberations with his generals (a different post entirely). Briefly, his military decisions were grounded in his understandings of races, and since his understandings of race were wrong, they were bad decisions. Again, that’s a different post (involving the Hitler Myth).

For this post, what matters is that German (European, to be blunt) cultural rhetoric provided a lot of support for essentializing the evil of those groups (lefties, homosexuals, Sintis anbd Romas, union leaders, Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, “mentally retarded”) because that rhetoric assumed that there was a clear distinction between “them” and “us” and that the differences were biological (that is, grounded in genes and incapable of genuine change).

But, as in the US, while people would support the lynching here and there of out-group members, disproportionate incarceration rates, polite racism (social exclusion, racist employment practices, shunning people in intergroup marriages), the same people who believed that that group is essentially evil balked at government-sponsored violence in front of their eyes (Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution is elegant on this). Prior to the war, most Germans didn’t want all the Jews in Europe to be killed, and they probably wouldn’t have supported Hitler in 1933 had he said that was what he would do. But he didn’t say it, and they supported his putting in place the systems, policies, and processes (especially one-party government, an openly politicized and authoritarian police force, and personal loyalty to him being the central value—more on all those below), because they were okay with the kind of expulsions and restrictions they thought Hitler had in mind for those kind of scary Others.

I’ve given so much background on eugenics/genetics because I think that one mistake that people make when they think they would recognize Hitler and resist (or believe that comparing their beloved authoritarian to Hitler is a ridiculous analogy) is that they think Hitler started off by calling for genocide based on wacky science. He didn’t initially explicitly call for genocide (or, at least, people didn’t hear him saying that, and he gave himself a lot of plausible deniability), and most of his intended audience wouldn’t have seen the science as wacky.

So, when we’re worried about whether this leader is like Hitler in troubling ways, we shouldn’t be looking for someone who will use early-twentieth century genetics to argue for exterminating Jews. We also shouldn’t be looking for someone who will cite obviously whackjob “science” or fringe experts to support the bizarre notions of some marginalized group. We should worry more about a leader who is citing experts whose “science” can’t withstand the rigors of academic argument, who have had to form their own journals and organizations, but whose claims are attractive both to authoritarian leaders and to most people because they confirm common beliefs. The most important failure of those experts (and the propaganda supporting and promoting them) is that neither they nor their supporters can make arguments that are both internally consistent and apply the same rhetorical/logical standards across groups.

[image from wikimedia commons: http://wikivisually.com/wiki/Ludwig_Cr%C3%BCwell]

A few years ago, I was talking to one of those young people raised to believe that Reagan was pretty nearly God, and he said to me, “At first I was mad when people said Reagan has Alzheimer’s but then I decided that it didn’t matter.”

A few years ago, I was talking to one of those young people raised to believe that Reagan was pretty nearly God, and he said to me, “At first I was mad when people said Reagan has Alzheimer’s but then I decided that it didn’t matter.”

A large number of the defendants in the Haymarket Trial (concerning a fatal bomb-throwing incident at a rally of anarchists–photo left) were immigrants or children of immigrants; by the early 20th century, people arguing that this group had dangerous individuals could (and did) cite examples like Emma Goldman (a Jewish anarchist imprisoned for inciting to riot), Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (Italian anarchists executed murder committed during a robbery), Jacob Abrams and Charles Schenck (Jews convicted of sedition), and Leon Czolgosz (the son of Polish immigrants, who shot McKinley). Even an expert like Harry Laughlin, of the Eugenics Record Office, would testify that the more recent set of immigrants were genetically dangerous (they weren’t—his math was bad).

A large number of the defendants in the Haymarket Trial (concerning a fatal bomb-throwing incident at a rally of anarchists–photo left) were immigrants or children of immigrants; by the early 20th century, people arguing that this group had dangerous individuals could (and did) cite examples like Emma Goldman (a Jewish anarchist imprisoned for inciting to riot), Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (Italian anarchists executed murder committed during a robbery), Jacob Abrams and Charles Schenck (Jews convicted of sedition), and Leon Czolgosz (the son of Polish immigrants, who shot McKinley). Even an expert like Harry Laughlin, of the Eugenics Record Office, would testify that the more recent set of immigrants were genetically dangerous (they weren’t—his math was bad).