Trump is commonly accused of being a demagogue. So were Obama, Reagan, FDR, Lincoln, and, well, pretty much every rhetorically effective President, and so are Keith Olbermann, Rush Limbaugh, Rachel Maddow, Bill O’Reilly, Ann Coulter, Michael Moore, Louis Farrakhan, Alex Jones. MLK was frequently condemned as a demagogue, which is interesting, since he’s now presented as the civil and moderate choice. I’ll come back to that.

In other words, the term “demagogue” is what scholars of rhetoric would call a “devil term”—it’s a term meaning you don’t like that person.

Using it that way is profoundly factional—demagogues are the political leaders of that party. That use of the word demagogue, I’ll argue, fuels demagoguery. In this talk, I want to consider what it would mean to think about demagoguery in a way that would enable us to identify demagoguery in our leaders, in our way of thinking about politics, in how we argue. And I want to point to some more productive ways to do all of those.

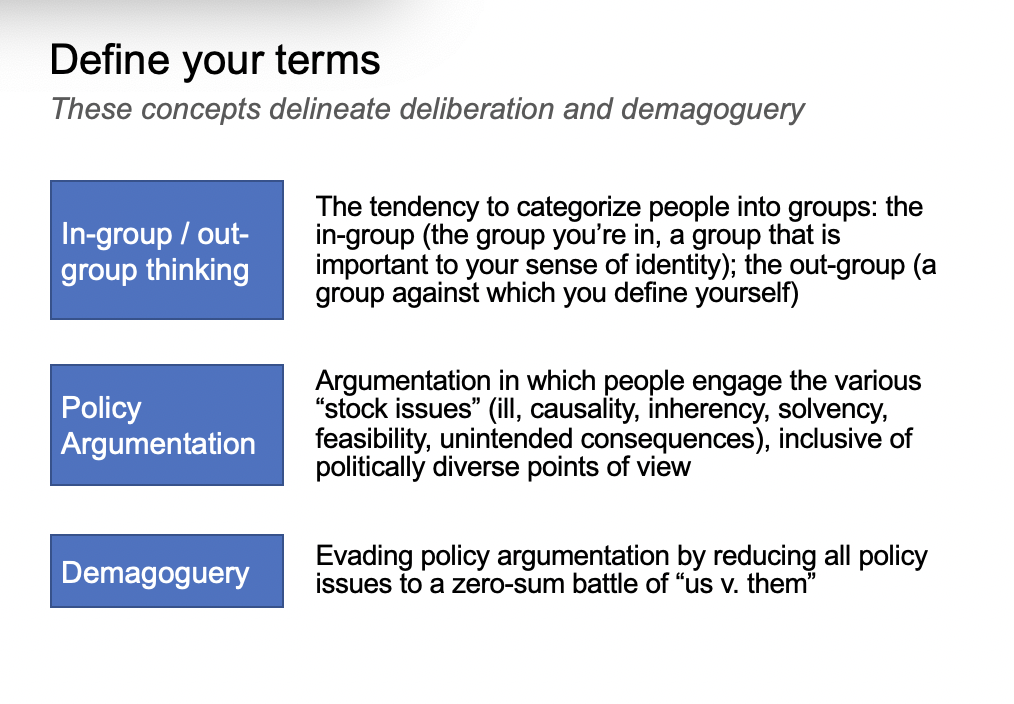

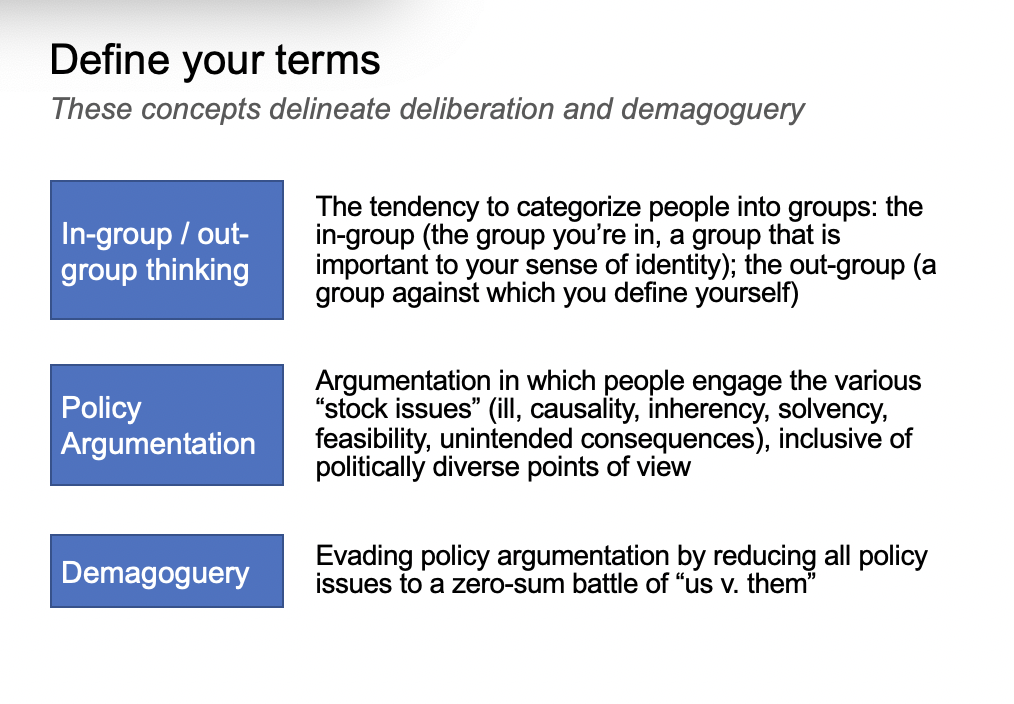

In this talk, I’m going to emphasize three concepts: in-group/out-group thinking; policy argumentation; and demagoguery.

When I began this talk, or perhaps even when you heard I would give this talk, you paid attention to cues as to whether I agree or disagree with your politics. If you decided, on the basis of various cues about my group identity (I’ll explain that in a bit), that I’m in your in-group, then you relaxed, your shoulders might have dropped, and you prepared to listen to what I have to say. If you decided I’m in an out-group, you invoked all of your critical thinking apparatus, you sat up straighter, making even your body reject what I was going to say.

That’s called in-group/out-group thinking.

In social psychology, the “in-group” is not the group in power; it’s the group you’re in. If being vegan is important to your sense of identity—if it’s something you tell others about yourself—then “vegans” is one of your “in-groups.” (We all have many in-groups.) It doesn’t matter that, in terms of cultural and political power “vegans” is a very marginal groups; it’s an in-group for you.

If being a “vegan” is an important identity for you (an in-group) then you probably have some group (or groups) you think of as being opposed to you—an out-group. Perhaps it’s omnivores, Romaine eaters, Nancy Pelosi, Republicans, people you’ve decided are “unhealthy,” lizard men. What matters is whether the pro-vegan groups in which you hang out share a sense that you are an “us.” And that “us” implies some “them” Sometimes there is more than one out-group. At U of Texas, it’s the Aggies (Texas A&M) and Sooners (U of Oklahoma). At A&M, it’s the Longhorns (U of Texas) and the Tigers (LSU). So, they aren’t always perfectly symmetrical.

We attribute far too much importance to in-group and out-group identities—we’re more likely to trust someone we perceive as “in-group” even if the issue at hand has nothing to do with that group. Whether someone else is vegan shouldn’t influence your willingness to buy a car from them, find their stance on immigration more credible, rely on their judgment about technical issues, but perception of shared group membership does exactly that: a person who shares one in-group with us is likely to be more trusted on irrelevant topics. People are more likely to trust and prefer others who share a birthday (Finch &Cialdini 1989; Burger et al. 2004; Walton et al. 2013), a first name (Burger et al. 2004), first-letters of a name (Hodson et al. 2005), facial similarities (Bailenson et al. 2008), even an invented category like sharing a rare “fingerprint type” (Burger et al. 2004) when deciding how to vote, how to distribute money, whether to invest with or buy something from a person—and those shared characteristics are all completely irrelevant.

The in-group is partially constituted by the out-group (we are who we are because we are not them). And someone can activate in-group favoritism by signaling that they feel animosity toward an out-group. My husband is an Aggie, and I teach at U of Texas. More than once a salesperson has seen my husband’s Aggie ring, and said something to both of us about how awful the Longhorns are. One of the more entertaining times this happened, it was when we were buying a car for me. The salesman simply assumed my husband hated Longhorns, and that my husband did the thinking for both of us.

We have a tendency to reason from identity—to look at someone and make a quick assessment as to whether they are reliable, credible, intelligent, ethical. And then, having made that determination, we process other information about them differently. That determination, however, is likely to be largely on the basis of in-group favoritism. And, once we’ve decided they’re in-group and reliable and so on, then we’ll use what social psychologists call “motivated reasoning” in order to try to confirm our initial perception. Our sense of ourselves as good people, and a good judge of people, is now tied up in confirming that our initial assessment of them was correct.

It would be uncomfortable to admit that we were wrong in our assessment of our in-group; it is pleasurable to feel that we (and people like us) are, if not always entirely right, at least never as bad as the out-group.

The dominant model of how we reason is what is often called “naïve realism.” It says that, if we’re going to make a decision, we should first try not to have any preconceptions (this isn’t possible, by the way). We should first look at the data, perceive the information, then reason. You can make sure that you’re right by going through this process again.

The dominant model of how we reason is what is often called “naïve realism.” It says that, if we’re going to make a decision, we should first try not to have any preconceptions (this isn’t possible, by the way). We should first look at the data, perceive the information, then reason. You can make sure that you’re right by going through this process again.

That isn’t how it actually works.

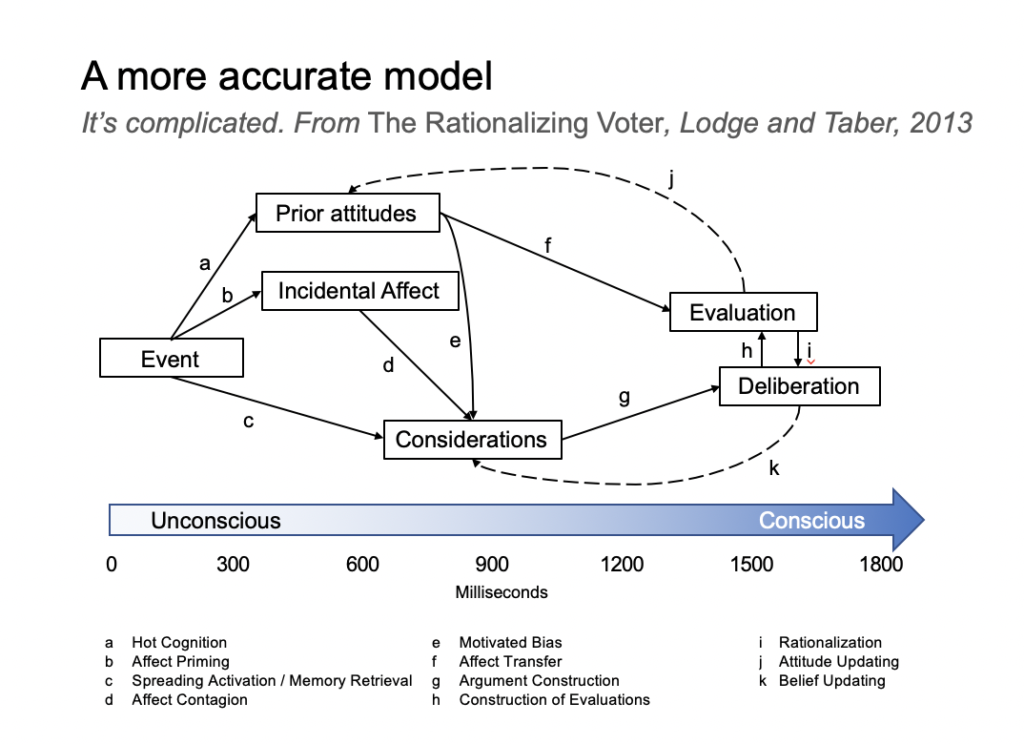

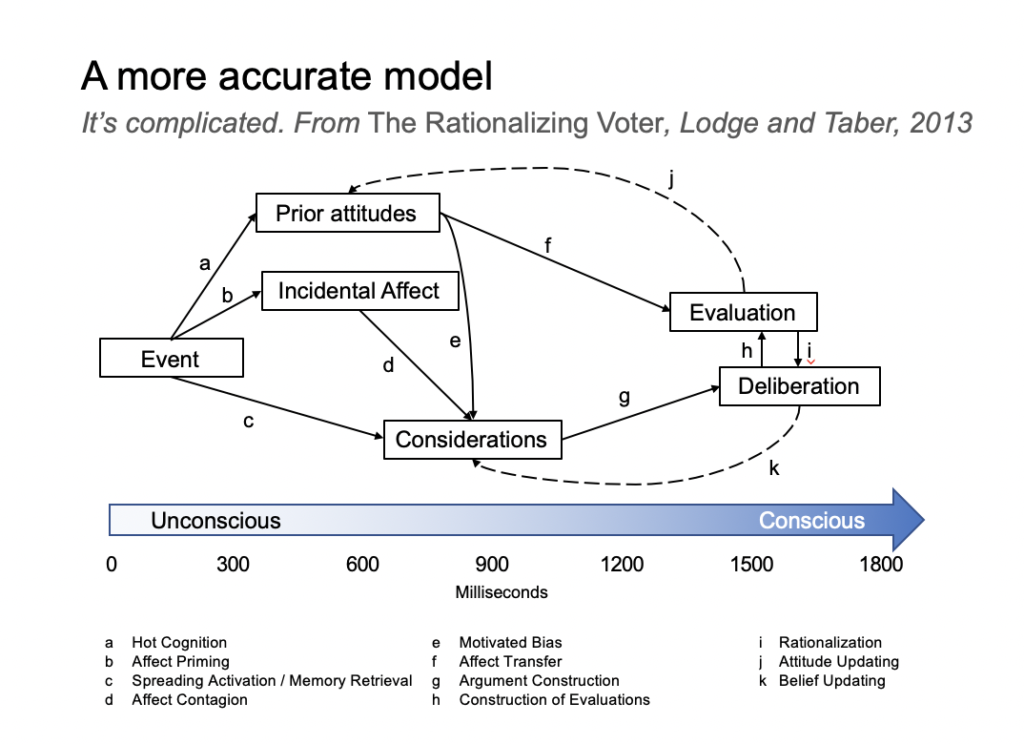

Imagine that we meet someone, call him Chester, and we want to figure out if he is ethical and reliable.

This is probably what the process is.

Something happens—you meet Chester. You have various prior attitudes—such as your beliefs about the topics Chester brings up, and the affect you’ll have about Chester/the incident that are incidental (that he reminds you of someone you like, that he looks like you, shares your birthday, you are hangry). These non-conscious factors lead to considerations about which you might be aware (Chester seems nice; Chester seems like a jerk; Chester seems to have the opposite of your politics). You might deliberate about Chester, all the time unaware of the way that your evaluation of Chester is so heavily influenced by those non-conscious factors.

Our determination isn’t emotional, exactly—it’s closer to what Aristotle called “intuition” and what many cognitive psychologists call “System 1” thinking.

Research is clear that we can’t suppress or ignore those non-conscious factors because we can’t do anything about them as long as they are non-conscious. Some cognitive psychologists (including Lodge and Taber) have tried telling people to think carefully, to take their time, to check their reasoning, and yet they still find that people are still significantly (and non-consciously) relying on motivated reasoning that is largely confirming the beliefs and affects that come from the non-conscious signals (triggers, or frames, depending on what metaphor you want to use). I’m much more hopeful about it, because I think Lodge and Tabor are right insofar as they are testing whether people will quickly give up important beliefs—that is, in a single sitting—but that isn’t how political reasoning necessarily works.

A lot of the experiments on these issues about people changing their minds involve bringing people into a psych lab, determining their hot commitments, giving them disconfirming information of those beliefs, and then noting that people don’t change their beliefs (or don’t change them on the basis of rational argumentation). But it wouldn’t be rational to abandon an important belief because someone in a pysch lab gave you new information. People do change our beliefs, for all sorts of reasons and in all sorts of ways, and some of those narratives of personal change involve rational argumentation (such as those in How I Changed My Mind About Evolution).

Let’s set that aside, and talk about demagoguery.

Demagoguery works by appealing purely to those kinds of non-conscious considerations, ratcheting them up with dog whistles, claims of existential threat to the in-group, reframing all policy issues into a war between the in- and out-group that is best won by pure loyalty to the in-group (and whatever leaders happen to best embody the in-group).

Politics is about policies. Ultimately, political determinations are decisions about which policies we should pursue, and it’s relatively clear what is a helpful way to argue about policies—policy argumentation.

Policy argumentation can (and probably should) happen any time people are deliberating a new course of action. There are, loosely, two kinds of cases that participants might make: affirmative (arguing for a particular course of action) or negative (arguing against a course of action someone else has advocated).

The affirmative case has two parts: the “need” (showing we have a problem and need a solution), and the “plan” (where a plan is described and defended.)

Within each part, there are certain “stock issues” (sometimes called “stases”—the traditional term for them).

Need:

-

-

- there is a problem (ill or need);

- it’s very serious;

- it is caused by X;

- it will not go away on its own.

Plan:

-

-

- here is my plan;

- my plan solves the problem (ill or need) I identified in the first part of my argument (solvency);

- my plan is feasible (feasibility);

- my plan will not cause more problems than it solves, or cause a worse problem than it solves.

A negative case refutes the argument on any (or all) of those stases.

What happens in a culture of demagoguery is that rhetors spend a lot of time on the need part of the case—and the “ill” (or problem) is that there is an out-group who is the cause of our problems. They are dangerous. We are, this argument runs, faced with extermination, and we don’t have time to deliberate (this is what the philosopher Giorgio Agamben calls “the state of exception”).

Because the problem is the presence and power of an out-group, the solution is, at least, their exclusion from policy discourse, and perhaps their exclusion from our community, or even their extermination.

The “plan” such as it is (and it isn’t much) is that you should throw all of your support behind me, or behind my party, or behind the plan I propose. Instead of arguing solvency or feasibility, demagoguery shifts back to need, or attacking critics as necessarily “them.”

Let me give an example.

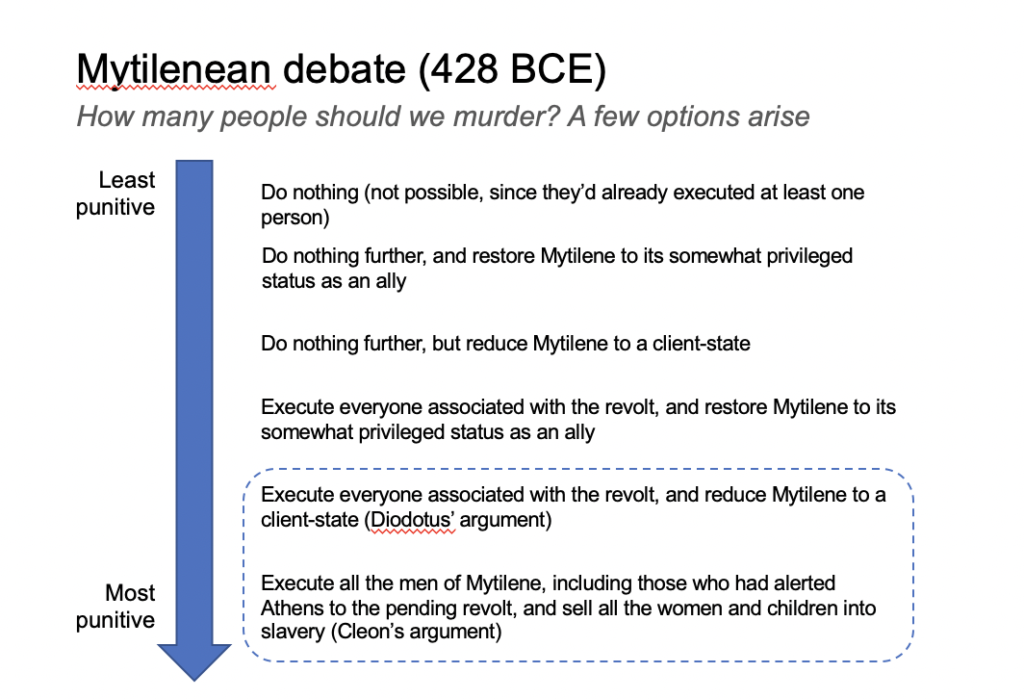

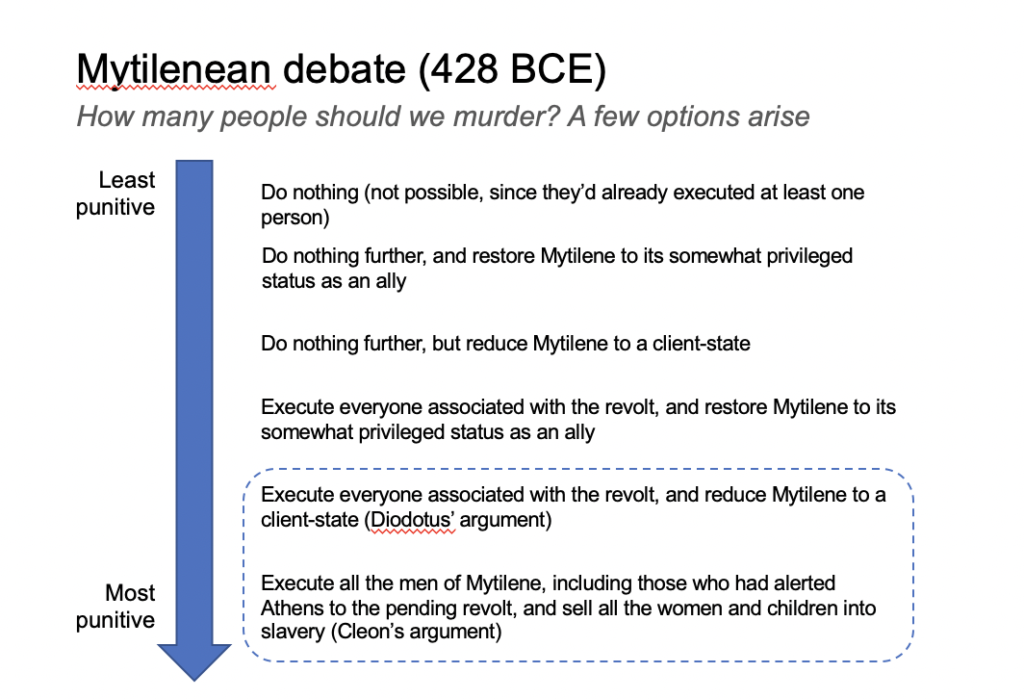

In 428 BCE, Athens was in the midst of a long and nasty war with Sparta. Mytilene, a city-state on the island of Lesbos some distance from Athens, was an Athenian ally that had a pro-Sparta revolt. Athenian had been warned that a revolt would happen (by pro-Athenian Mytileneans), and was able to send Paches, a general, with a fleet to put down the revolt. He succeeded. The leader of the revolt was executed. Paches took prisoner people that seemed to have been the main ones involved in the revolt. The question was what Athens should do.

Athens had various options. One option not on the table was to do nothing—they’d already enacted execution. They could, however,

-

-

- Do nothing further, and restore Mytilene to its somewhat privileged status as an ally

- Do nothing further, but reduce Mytilene to a client-state

- Execute everyone associated with the revolt, and restore Mytilene to its somewhat privileged status as an ally

- Execute everyone associated with the revolt, and reduce Mytilene to a client-state (Diodotus’ argument)

- Execute all the men of Mytilene, including those who had alerted Athens to the pending revolt, and sell all the women and children into slavery (Cleon’s argument)

Thucydides, a historian living at the time, gives us his version of the debate that occurred in Athens. He says that, initially, the Athenians opted for the third, but woke up the next morning from a kind of rhetorical hangover, like texts from last night on papyrus, and had doubts. The debate was reopened.

Thucydides’ work is the beginning of a shift in the word “demagogue,” from a neutral term (leader of the demes—essentially the middle and working classes) to a negative term meaning a rhetor who argues a particular way. Thucydides didn’t much like Cleon, but he had no objection to leaders of the demes—the hero of his history is Pericles, who was also a leader of the demes. Thucydides’ opposition to Cleon came from his belief that Cleon’s way of arguing was disastrous for democratic deliberation. Aristophanes and Aristotle seem to have thought so too, and they have the same criticisms of how Cleon argued.

Cleon’s argument for mass killing relies on five claims:

-

- Athenians are soft, spend too much time deliberating, think too much, and don’t understand that an empire is based in terror;

- mass killing will terrorize all the other Athenian city-states into submission (the first recorded instance of genocide conceived as a rhetorical act). Once they see how brutally Athens responds to revolt, no one will ever dare revolt again;

- the Mytileneans hurt Athens and the only way to respond to injury is violence; to do nothing (which he claims is what his opposition is advocating) is to reward Mytilene for hurting Athens;

- his argument is so obvious that the only explanation for people arguing against it is that they are secretly in the pay of enemies of Athens;

- Athenians might be tempted to fall for those corrupt rhetors’ arguments out of feeling compassion for people who want to kill them.

If you map this argument back on to the “stock issues” of policy argumentation, you can see the problems with his argument.

Need:

-

-

- there is a problem (ill or need); his ill isn’t about the Mytileneans—it’s about how Athenians are weak-willed, too kind, too moved by argument, too prone to thinking about things, don’t act from anger (in other words, Cleon is telling a democracy that their problem is that they are a democracy);

- it’s very serious; he says Athens will lose its empire unless it toughens up and terrorizes everyone;

- it is caused by X; it’s caused by Athens having people who like deliberation;

- it will not go away on its own; he never mentions this.

Plan:

-

-

- here is my plan; he can assume that people know his plan from the arguments on the previous day—mass killing and enslavement;

- my plan solves the problem (ill or need) I identified in the first part of my argument (solvency); his plan does nothing as far as solving what he identified as the “ill”—that Athenians like to deliberate—the implied solution to that problem is that Athens should become a tyranny with him the tyrant; as far as the problem Athens is actually facing—what to do about its allies and client-states in the long war, he asserts, but doesn’t argue, that mass killing will terrorize the client-states;

- my plan is feasible (feasibility); nothing;

- my plan will not cause more problems than it solves, or cause a worse problem than it solves; nothing.

In other words, Cleon isn’t engaged in policy argumentation. Not even a little. Cleon isn’t even really arguing about the case at hand—he just asserts he’s right, and that anyone who disagrees with him is a traitor. Cleon’s argument isn’t about Mytilene—it’s about how Athenians should deliberate, and, he says, they shouldn’t—they should stop thinking and just listen to him. And notice that Cleon makes people who want to deliberate—the basis of democracy—a traitor to a democracy. That’s what demagoguery always does.

His argument isn’t about policy, but about identity. He divides the issue into an us (angry, manly, dominating, clear, decisive, realistic) and them (dithering, too compassionate, wanting to do nothing, deliberating). The first kind of person is right; the second has no legitimate argument to make, and should be silenced.

Cleon is arguing that politics isn’t about policies, but is a zero-sum battle between good (strong, manly, punitive, angry and yet in control, decisive, realistic) people who think in black and white terms and bad (people who believe in the processes of democracy). Cleon’s argument is an argument against democracy itself.

Cleon was trying to pretend his argument was rational, realistic, and clear-thinking, and that the opposition argument was fuzzy and compassionate. He was wrong on both counts.

Cleon’s entire argument was based on two fallacies: a false binary, and straw man (two fallacies often connected in demagoguery). [Go back to slide 7] As I mentioned earlier, Athens had many possible options in regard to Mytiline—no one was arguing for the position Cleon represents as “the opposition.” And Cleon never answers the argument that Diodotus actually makes.

That’s typical of demagoguery—turn a complicated array of possible policy options into a binary of “my way or nothing.”

Diodotus’ argument was for a more punitive position than anything done previously by Athens. Cleon represents it as doing nothing. That’s the straw man fallacy.

It’s also lying about his opposition. In general, when people engage in straw man fallacy, it’s either because they’re ignorant of the opposition argument (that is, they live in an informational enclave) or they know what it is and they choose to lie about it. And, if they lie about it, it’s because they don’t really have a good argument against what the argument actually is.

There was nothing compassionate or soft about the opposition argument. Personally, I find it heartless. Diodotus, his opponent, was arguing for execution of the people plausibly associated with the revolt. Diodotus, argued entirely on the grounds of policy argumentation (he hit the marks, which Cleon didn’t).

And, at least as Thucydides tells us, and is reasonable to infer from history, Cleon was wrong and his opponents were right. As Athens became increasingly punitive and authoritarian toward other members of its empires, it created enemies for itself, and allies for its enemies.

More important, Cleon’s kind of rhetoric became the norm. The most disturbing passage in Thucydides is his description of how the zero-sum factionalism of Greek city-states corrupted deliberation.

Thucydides says that the things previous valued in democracies—fairmindedness, inclusive deliberation, being willing to compromise, listening to various points of view, trying to argue well, striving to think things through, making party less important than polis—have all been lost. Instead, all that anyone cares about is their faction (we’d use the term “party”) winning, at any cost. Things we would find outrageous behavior if done by them we think perfectly fine if we do them; compromise, looking at various sides—that’s just dismissed as being a girly girl; wanting to take the time to think things through and get information, that’s just cowardice; not wanting to take the most extreme action right now—that’s just wanting to do nothing at all. They wanted leaders who were angry, unwilling to compromise, committed to the most extreme proposals, and refusing to work with anyone who disagreed. Blocking the actions of your opponent was just as good as actually getting anything done.

The democracies of this era had become cultures of demagoguery.

This tendency to frame all policy issues as a zero-sum choice between the two major factions would lead to Athens’ just plain dumb decision to invade Sicily, and to do so in such a way that it opened itself up to attack from Sparta. It would be the end of the Golden Age of Athens. That’s what happens in a culture of demagoguery. That’s what it did in Rome; that’s what it did in the various Italian republics; that’s what it’s done in many other democracies—from Germany in the 1930s to Venezuela now—abandoning inclusive policy argumentation in favor of reducing every argument to how your party can trounce the other destroys democracies. And we’re in that culture, and we have been for at least twenty years.

So, what do we do?

Well, there are a few things.

The notion that we can do anything useful about this by creating a third or fourth party won’t work. I used to think that, but reading more about Weimar Germany (which had over six parties) nipped that notion in the bud. Nor will ending straight-ticket voting do anything useful. It isn’t the parties that matter—I’m not even sure it’s how people vote that matters.

It’s how people argue that matters. It’s how you argue.

If you listen to me and think, “Oh, yeah, Those People do this all the time—they’re just Cleon,” you’re missing my point. You’re still engaged in demagogic reasoning. What matters is whether you are engaged in demagogic reasoning.

So, how do you stop that?

First, stop putting all issues into left v. right. That’s like trying to categorize all people as at this moment using their left hand v. at this moment speaking French. Some people are doing both, most people are neither, and it varies from moment to moment.

Second, get out of your informational enclave, and, when you put that with the first recommendation, that means don’t just flip between Maddow and Hannity, or Mother Jones and the Drudge Report. Toggling between highly partisan media doesn’t make you more informed; it just makes you more angry. Every reasonable political position has someone smart making a smart argument for it—find those smart arguments.

Instead of thinking left v. right, think about the array in regard to the relevant axes. For instance, for some issues this is my set of go-to sites.

I’d have a slightly different list for something about immigration, or religion, or the environment.

Third, simply asking yourself if you have reasons for your position doesn’t make you reasonable. Thinking you are not motivated by feelings doesn’t make you rational. It’s more useful if we think about a rational stance as one that meets two standards:

-

- you can imagine the circumstances under which you would change your mind—could your mind be changed by new data? what would that data be?

- you have listened to smart versions of opposition arguments. can you summarize your opposition’s argument in a way they would say was fair and accurate? have you looked at the data they’ve provided?

And a rational argument is one that argues in a way that you apply consistently– so, if your argument about one Constitutional amendment is grounded in the intentions of the people who wrote it, is that how you read all of them? If not, your argument isn’t rational.

Would you consider your way of arguing rational if made by your opposition—if you think your argument must be accepted because you can describe a personal experience to support it, would you abandon it if your interlocutor told you a personal experience of theirs to refute it? In other words, are you consistently treating personal experience as sufficient support?I’ve been going on a long time, so I’ll just mention a few resources that can be helpful. I really like the ten rules of two philosophers—Fran van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst (1984).

-

- Parties must not prevent each other from advancing standpoints or casting doubt on standpoints.

- A party that advances a standpoint is obliged to defend it if the other party asks him to do so.

- A party’s attack on a standpoint must relate to the standpoint that has indeed been advanced by the other party.

- A party may defend his standpoint only by advancing argumentation relating to that standpoint.

- A party may not falsely present something as a premise that has been left unexpressed by the other party or deny a premise that he himself has left implicit.

- A party may not falsely present a premise as an accepted starting point nor deny a premise representing an accepted starting point.

- A party may not regard a standpoint as conclusively defended if the defense does not take place by means of an appropriate argumentation scheme that is correctly applied.

- In his argumentation, a party may only use arguments that are logically valid or capable of being validated by making explicit one or more unexpressed premises.

- A failed defense of a standpoint must result in the party that put forward the standpoint retracting it, and a conclusive defense of the standpoint must result in the other party retracting his doubt about the standpoint.

- A party must not use formulations that are insufficiently clear or confusingly ambiguous and he must interpret the other party’s formulations as carefully and accurately as possible.

By the way, this isn’t saying that you have to treat everyone discussion this way—it’s just the set of rules for a rational argument. If you’re talking to someone who consistently violates the rules, you aren’t in a rational argument, regardless of what you do. This is a relationship that takes two. In addition, there are really worthwhile conversations that aren’t like this—a time you can’t persuade each other, but you can learn from each other.

The book Superforecasting has a great list of how to counteract the various cognitive biases we have. Philip Tetlock has listed those rules as the “Ten Commandments for Aspiring Superforecasters.” One of the most important premises of his work is that there is not a binary between being certain and being clueless. Pure certainty is a personal feeling, not a cognitive state—be willing to acknowledge that we live in a world in which we range from being able to be pretty certain to not at all certain, and we need to think about where on that continuum a decision is ranges. Tetlock says, there is a big difference between the amount of justifiable confidence we can have about who will win the 2019 World Series than who will win the 2050 one.

The last point I’ll mention is something that Diodotus says. Diodotus began his speech, not by talking about Mytilene, but by talking about talking. Diodotus said, “The good citizen ought to triumph not by frightening his opponents but by beating them fairly in argument.”

[slides by Alexander Fischer]

Citations

Applegate, Kathryn et al. (2016) How I Changed My Mind About Evolution: Evangelicals Reflect on Faith and Science. IVP Academic.

Bailenson, Jeremy N., et al. (2008). “Facial similarity between voters and candidates causes influence.” Public Opinion Quarterly 72.5, 935-961.

Burger, J. M., Messian, N., Patel, S., Prado, A. del, & Anderson, C. (2004). “What a Coincidence! The Effects of Incidental Similarity on Compliance.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(1), 35–43.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: A pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hodson, G., & Olson, J. M. (2005). “Testing the generality of the name letter effect: Name initials and everyday attitudes.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(8), 1099-1111

Kahneman, Daniel. (2013). Thinking Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Poehlman, T. et al. (2013). “The name-letter-effect in groups: sharing initials with group members increases the quality of group work” PLoS one, Vol. 8 , Issue 11

Tetlock, Philip. https://fs.blog/2015/12/ten-commandments-for-superforecasters/

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian Wars. (1998). Trans. Steven Lattimore. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Walton, G. M., Cohen, G. L., Cwir, D., & Spencer, S. J. (2012). “Mere belonging: The power of social connections.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 513-532.

The dominant model of how we reason is what is often called “naïve realism.” It says that, if we’re going to make a decision, we should first try not to have any preconceptions (this isn’t possible, by the way). We should first look at the data, perceive the information, then reason. You can make sure that you’re right by going through this process again.

The dominant model of how we reason is what is often called “naïve realism.” It says that, if we’re going to make a decision, we should first try not to have any preconceptions (this isn’t possible, by the way). We should first look at the data, perceive the information, then reason. You can make sure that you’re right by going through this process again.