Over time, I have evolved to having students submit “microthemes” (the wrong word) before class, and I use them for class prep. I keep getting asked about that practice, so this is my explanation.

Here’s what I tell students in my syllabus.

———

Microthemes. Microthemes are exploratory, informal, short (300-700 words) responses to the reading (they can be longer if you want). They have a profound impact on your overall grade both directly and indirectly; doing all of them (even turning in something that says you didn’t one) can help your grade substantially. Since the microthemes are on the same topics as the papers, they also serve as opportunities to brainstorm paper ideas.

The class calendar gives you prompts for the microthemes, but you should understand those are questions to pursue in addition to your posing questions. That is, you are always welcome to write simply about your reaction to the reading (if you liked or disliked it, agreed or disagreed, would like to read more things like it). Students find the microthemes most productive if you use the microtheme to pose any questions you have–whether for me, or for the other students. They’re crucial for me for class preparation. So, for instance, you might ask what a certain word, phrase, or passage from the reading means, or who some of the names are that the author drops, or what the historical references are. Or, you might pose an abstract question on which you’d like class discussion to focus. I’m using these to try to get a sense whether students understand the rhetorical concepts, so if you don’t, just say so.

A “minus” (-) is what you get if you send me an email saying you didn’t do the reading; you get some points for that and none for not turning one in at all. So failure to do a bunch of the microthemes will bring your overall grade down. If you do all the microthemes, and do a few of them well, you can bring your overall grade up. (Note that it is mathematically possible to get more than 100% on the microthemes—that’s why I don’t accept late microthemes; you can “make up” a microtheme by doing especially well on another few.)

Microthemes are very useful for letting me know where students stand on the reading–what your thinking is, what is confusing you, and what material might need more explanation in class (that’s why they’re due before class). In addition, students often discover possible paper topics in the course of writing the microthemes. Most important, good microthemes lead to good class discussions. The default “grade is √, except for ones in which you say that didn’t do the reading, or check plusses, plusses, or check minus. (So, if you don’t get email back, and it wasn’t one saying you hadn’t done the reading, assume it got a √.)

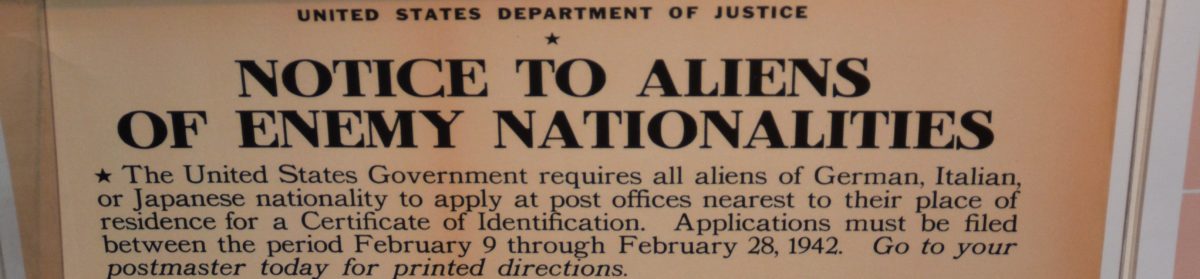

If you get a plus or check plus (or a check minus because of lack of effort), I’ll send you email back to that effect. (I won’t send email back if it’s a minus because you said you didn’t do the reading—I assume you know what the microtheme got.) If you’re uncomfortable getting your “grade” back in email, that’s perfectly fine—just let me know. You’ll have to come to office hours to get your microtheme grade. You are responsible for keeping track of your microtheme grade. There are 26 microtheme prompts in the course calendar; up to a 102 will count toward your final grade. There are five possible “grades” for the microthemes [the image at the top of this page].

Please put RHE330D and micro or microtheme in the subject line (it reduces the chances of the email getting eaten by my spam filter). Please, do not send your microthemes to me as email attachments–just cut and paste them into a message. Cutting and pasting them from Word into the email means that they’ll have weird symbols and look pretty messy, but, as long as I can figure out what you’re saying, I don’t really worry about that on the microthemes. (I do worry about it on the major projects, though.) Also, please make sure to keep a copy for yourself. Either ensure that you save outgoing mail, or that you cc yourself any microtheme you send me (but don’t bcc yourself, or your microtheme will end up in my spam folder).

=========

I find that I can’t explain microthemes without explaining how I came around to them.

I have three degrees in Rhetoric from Berkeley, for complicated reasons, none of which my ever involved deciding at the beginning of one degree that I would get the next. I always had other plans. And, for equally complicated reasons, I ended up not only tutoring rhetoric but acting as an informal TA (what we now call a Teaching Fellow) for rhetoric classes at some point (perhaps junior or senior year). And then I was the TA (a person who grades something like 3/5 of the papers and taught 1/5 of the course—a great practice) for two years, and then the Master Teacher (graded 2/5 of the papers and taught 4/5 of the course). Berkeley, at that point, was a very agonistic culture, and so “teaching” involved waking into class and asking what students thought of the reading, I was just a kind of ref at soccer game.

The disadvantage of all that time at one place and in one department was that I was very accustomed to a particular kind of student. Teaching rhetoric at Berkeley at that moment in time (rhetoric was not the only way to fulfill the FYC requirement and drew the most argumentative students) meant managing all the students who wanted to argue. And, given my Writing Center training, I spent a lot of time in individual conferences. My teaching load as a graduate student was one class per quarter.

That training prepared me badly in several ways. First, it was a rhetoric program, and the faculty were openly dismissive of research in composition. Second, I was only and always in classrooms in which the challenge was how to ref disagreement. Third, I adopted a teaching practice that relied heavily on individual conferences.

I went from that to teaching a 3/3 (or perhaps 3/2—I was always unclear on my teaching load) in the irenic Southeast. Students would not disagree with each other—if they had to, they would preface their disagreement with, “I don’t really disagree but…” In an irenic culture, people actually disagree just as much as they do in an agonistic one, but they aren’t allowed to say so.

Granted, we can never get students to give us some weird kind of audience-free reaction to the reading (if there is such a thing), but I had lost the ability to get a kind of almost visceral reaction to the reading, a sense of the various disagreements that people might have. I also didn’t have the time to meet with students individually as much.

I tried various strategies, such as students keeping a “sketchbook” (I can’t remember who suggested that), in which students responded to the reading, but I couldn’t read the book (since, in those days, it was a physical book) till after class, by which time it was too late for me to respond to what they’d said. But I did notice that students’ responses to the reading were more diverse than what ever happened in class. For one thing, students writing to me would say things they wouldn’t say in front of class.

Sometimes too much so. There was a problem with students telling me more about how the reading reminded them of very private issues. At some point I tried calling them “reading responses,” but that name flung students too often in the opposite direction, and they just summarized the readings.

I moved on to a place and time with more digital options—discussion boards, blogs—and found that they were great in lots of ways. Introverts who won’t talk in class will post on a blog, but there was an issue of framing. In discussions, of any kind, the first couple of speakers frame the debate, and future speakers generally respond from within that frame. So, as opposed to the “sketchbooks,” the blog posts were dialogic rather than diverse (although there weren’t as many plaints about a romantic partner). And even I recognized that a student could easily fake having done the reading, simply by piggybacking on other posts. The discussion board got me no useful information about how my students had reacted to the reading.

“Reading responses” was too private, but blogs were too much prone to in-group pressures.

I honestly don’t know where I found the term “microthemes,” and it’s still wrong (although less wrong than it used to be). Were I to do my career over, I would find a different term, but I don’t know what it would be.

The problem is that it has the term “theme” in it, and so students who have been trained to write a “theme” try to write a five-paragraph essay. Since fewer high school teachers ask for themes, this problem seems to be dissipating.

There are a lot of models of what makes for good teaching, and one is that a good teacher has students engage with each other—a good teacher is the teacher I was at Berkeley, just letting students argue with each other, and acting as a ref at a soccer game. And, to be honest, that was fine at Berkeley, because, while racists and misogynists and homophobes might have whined (and did) that people disagreed with them, people disagreed with them. Their whingeing was that someone disagreed with them.

It got more complicated in an irenic culture, when students didn’t feel comfortable disagreeing with anything. And, by the time I’d found about the disagreement, it was hard to figure out how to put into the class (I learned that you do it by your reading selections, but that’s a different post). The irenic culture meant that, if a student said something racist, other students didn’t feel comfortable saying anything about it (especially if the racist thing was within the norms of what I always think of as “acceptable racism”).

Behind all of this is that we are at a time when there is a dominant and incoherent model of what makes good teaching: it is about having a powerpoint (meaning you aren’t listening to what these students need, and you’re transmitting knowledge you already think they know) and having discussion in class in which all student views are equally valid.

That model is fine for lots of classes, but it’s guaranteeing a train wreck if you’re teaching about racism, or any issue about which a teacher is willing to admit that racism might have an impact. Since we’re in a racist world, asking that students argue with one another as though their positions are equally valid, when racism ensures they aren’t equally valid, is endorsing racism.

Yet, in a class about racism, it’s important to engage the various forms of racism that are plausibly deniable racism. Most racists don’t burn crosses or use the n word, but they make claims that they sincerely think aren’t racist. As I’ve said, this is rough work, and it really shouldn’t be on the shoulders of POC—white faculty should take on the work of explaining to white racists who think they aren’t racist that they are.

If we think of the discursive space of a class as the moment of the class, then this is almost impossible to do, and it’s racist to think that non-racist students should have to explain to racist students that they’re racist. It’s racist because the notion that a classroom is some kind of utopic space in which the hierarchies of our culture are somehow escaped enables the hierarches to skid past consideration, and thereby, those hierarchies are enabled by “free” discussion.

But, if you’re teaching a class in which you want to persuade people to think about racism, you have to have a class in which people can express attitudes that might be racist. Open discussion won’t work, and blogs still have a lot of discursive normativity, and so you need a way in which students can be open with you and say things they don’t want to say in front of other students.

And so you have microthemes.

Students feel more free to express views that they wouldn’t say in front of other students, and they’ll tell you if they haven’t done the reading, so I walk into class knowing how many students didn’t do the reading.

There are some disadvantages. You can’t reuse old lecture notes; you can’t prepare a powerpoint. And, since I’m the one presenting views that students have, there is a reduction in student to student conversation (it gets me hits on teaching observations but, since student to student interaction is deeply problematic in terms of power, I’m okay with that).

And, since undergraduate lives are, well, undergraduate lives, students don’t always remember what they’ve said in microthemes. And there is a tendency for students (especially graduate students) to feel that, since they’ve already told me what they think, they don’t need to say it in class.

But, still and all, I wish I’d adopted microthemes years before I did, but with a different name.

Why all the Warren/Sanders hate?

Why all the Warren/Sanders hate?