Cicero, in De Inventione, said that, if you are presenting an argument with which your audience already agrees, you land your thesis in the introduction. If you are arguing for something your audience disagrees, you delay your thesis. Oddly enough, as I’ve taught a lot of workshops across the disciplines for scholarly writing, I’ve found that Cicero is right. When people are making an argument their audience doesn’t want to hear, they delay their thesis, even in scholarly arguments (they have a partition instead, or sometimes a false thesis).

I have always required that my students write to a reasonable and informed opposition, and that means delaying their thesis, delaying their claims till after they’ve given evidence, beginning by fairly representing the opposition, getting evidence from sources their opposition would consider reliable, giving a lot of evidence, and explaining it well. I don’t have those requirements because I think this is what all teachers should teach–we shouldn’t. Since student writing requires announcing a thesis, giving minimal explanation, starting paragraphs with main claims, and various other non-persuasive strategies, it is responsible for people teaching the genre of college writing to teach students how to do that. I’m describing that pedagogy because I want it clear that I understand the value of reaching out to an audience and trying to find common ground.

The hope of rhetoric is that we can avoid violence by talking.

We use violence when we believe that we are in a world of existential threat, when we believe that the out-group is engaging in actions that might exterminate us. Sometimes that belief is an accurate assessment of our situation—Native Americans through the entire nineteenth century, Jews in Nazi Germany, free African Americans in the antebellum era, powerful African Americans in most of the nineteenth and twentieth century, Armenians in Turkey, and so on. Whether violence or non-violence is the most strategic choice for the people being threatened with extermination is an interesting argument. For me, whether third-party groups should use violence to stop the extermination is not an interesting argument. The answer is yes.

Sometimes the rhetoric of in-group extermination is simultaneously right and irrational. Antebellum white supremacists correctly understood that abolition would mean that their political monopoly would end were African Americans allowed to vote. Their sense of existential threat was the consequence of so closely and irrationally identifying with white supremacy–with believing that losing that system was essentially extermination. It wasn’t; it was just losing the monopoly of power. Racist demagoguery enabled them to persuade themselves that, because they were threatened with extermination, they were not held by any bounds of ethics, Christianity, legality.

That’s how demagoguery about existential threat works, and that’s what it’s intended to do. It’s designed to get people to overcome normal notions that we should follow the law, be fair to others, listen to others, treat children well, be compassionate, behave according to the ethical requirements of the religion we claim to follow, and so on by saying that, while we are totally ethical people, right now we have to set all that aside–because we’re faced with extermination. When, actually, we’re just faced with losing privilege. That connection is sheer demagoguery.

Republicans now correctly understand that allowing everyone to vote would end their political monopoly. White evangelicals correctly realized that they were losing the political power they had with Bush and Reagan. Coal miners are faced with a world that doesn’t need a lot of people to have that job. Racists, homophobes, and bigots of various kinds are being told they need to STFU. None of these groups are faced with being actually exterminated, but they are faced with their political power being lessened. And too many people in those groups listen to media that has taken the Two-Minute Hate to 24/7 demagoguery about existential threat.

Trump supporters have spent years drinking deep from the Flavor-Aid of the pro-GOP Outrage Machine, and so they believe a lot of things. They believe they’re the real victims here, that the media is against them, that white people are about to be persecuted, that there is no legitimate criticism of their position, that libruls have nothing but contempt for them and think they’re racist,that they are so threatened with extermination that anything done on their behalf is justified.

And here I have to stop and say that authoritarians (regardless of where they are on the political spectrum, and authoritarians are all over the place, but at any given time they tend to congregate on a few spots) misunderstand the concept of analogy. If, for instance, I say that supporters of Hitler reasoned the same way that squirrel haters are now reasoning, I am not saying that they are the same people (or dogs) in every way. I am not making an identity argument; I am making an argument about reasoning.

But, all over the political spectrum, people who are, actually, reasoning the way that people who supported the Nazis reasoned, are outraged at the comparison. It isn’t a comparison about identity; it’s a comparison about methods of reasoning.

We aren’t in a crisis of facts. Everyone has facts. We’re in a crisis of meta-cognition. We have a President who is severely cognitively impaired and obviously declining rapidly, fires people who disagree with him, can’t make a coherent argument for his policies, doesn’t argue from a consistent set of principles. Trump supporters can find ways to support him, but none of those ways fit all the other ways, let alone are ways that explain their opposition to out-group members. The debacle about ingesting disinfectants is just the latest.

We are at a point when the defenses of Trump are that he doesn’t have the skills to be President–he is thin-skinned (he was so obsessed with impeachment that he couldn’t pay attention to anything else), lies all the time (his height, weight, the number of people at his inauguration, whether he was talking to Birx), forces other people to lie on his behalf (such as Trump supporters lying that he was so obsessed with impeachment he couldn’t do anything else, although he also said that wasn’t true), refuses to listen to anyone (which his supporters defend by blaming the disloyal people), gives briefings when he doesn’t actually know what he’s talking about (every briefing), and often says things that aren’t what he meant (every defense of Trump).

What I’m saying is that Trump supporters grant all the criticisms of Trump–their argument is that he’s incompetent.

But their defenses of him show something about them–that they can’t put forward a rational defense of him. I mean “rational” in the way that theorists of argumentation use the term. They can’t put forward an argument for Trump without violating most of rules of rational-critical argumentation. (And, I’d love to be proven wrong on this, so if any Trump supporters want to show me an argument for him that follows that rules, I’d love to see it.)

In other words, support for Trump isn’t about any kind of rational support for his enhancing democratic deliberation, nor even his trying to ground his political decisions and rhetoric in a coherent ideology, but a “fuck libruls, we’re winning” rabid tribal loyalty that eats its own premises.

Trump happens to be the most obvious example right now, but, again, all over the political spectrum are people who can’t defend their positions in a coherent and consistent way. They can defend their positions—but by giving evidence that relies on a major premise they don’t believe, engaging in kettle logic, or whaddaboutism.

If we’re paying attention to Cicero, then we should find common ground with them, be fair to their representation of their own argument, and delay our theses. And, as I said, I think that is great advice.

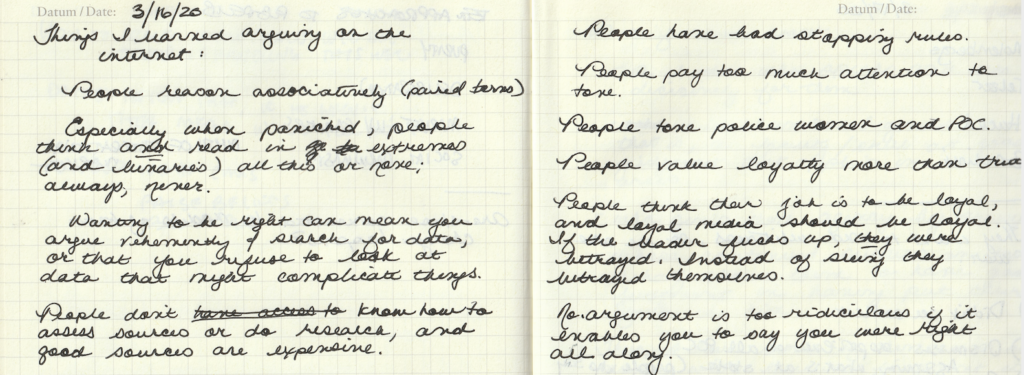

But it isn’t useful advice when we’re arguing with people who, as soon as they sense you are going to criticize them, refuse to listen because they think they know what you are going to argue, and they know they shouldn’t listen. People well-trained in what the rhetoric scholars Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrecths-Tyteca called “philosophical paired terms” just assume that, if you’re saying Trump isn’t the best, then you are part of the ruling elite–just as Stalinists used to say that Trotsky must be a capitalist, since he criticized Stalin; Nazis said that anyone who criticized Hitler must be a Jew; anyone who opposed McCarthy was a communist; slavers said that anyone who criticized slavery must want a race war. If you aren’t with us, you are against us.

In the 1830s, the major critics of slavery were predominantly Quakers and free African Americans who described slavery accurately, but that (accurate, it should be emphasized) description hurt the feelings of slavers.

Slavers and pro-slavery rhetors said that any criticism of slavery was an incitement to slave rebellion. Much like pro-Trump rhetoric that inadvertently gives away the game–their argument is that he doesn’t have the skillset to be a good President–this rhetoric gave away that slaves hated being slaves, and that the actual conditions of slavery were indefensible.

Many people tone-policed the anti-slavery rhetors (to the extent of having a gag rule in Congress, which is pretty amazing if you think about it). Oddly enough, some anti-slavery rhetors said that these (accurate) descriptions of individual slavers beating and raping slaves were inflammatory, and so some of them tried to write conciliatory anti-slavery tracts. They were accused of fomenting slave rebellion.

Individuals can be persuaded to change their ways on the basis of individual interactions, and there are a lot of anecdotes saying that can work. That’s how individuals leave cults, for instance. But conciliatory rhetoric to groups of people who are drinking deep from a propaganda well is a waste of time.

If you have a personal connection to someone who is a Trump supporter, then building on that personal connection might work, but it’s worth noting that the notion of being able to change people is why people stay in abusive relationships.

But, when we’re talking about relative strangers–the strange world of social media interlocutors–then I don’t think engaging the claims is as useful as pointing out the inability to follow the basic rules of rational-critical argumentation. When people are fanatically committed to an ideology that is internally incoherent and incapable of defended in rational-critical argumentation—and that’s where support of Trump is now—no level of “let’s be inviting to them” will persuade them. It’s worth the time to be precise in our criticisms of their position, but not because being precise will be more or less rhetorically effective. It’s worth the time to be right.

People in rhetoric need to understand that some people are engaged in good faith argumentation, and some aren’t, and we behave toward them differently.

It is impossible to defend Trump through rational-critical argumentation.

Shaming Trump supporters on that point is a good rhetorical strategy. Whether you do that through conciliation with individuals or through generally pointing it out is an audience choice.