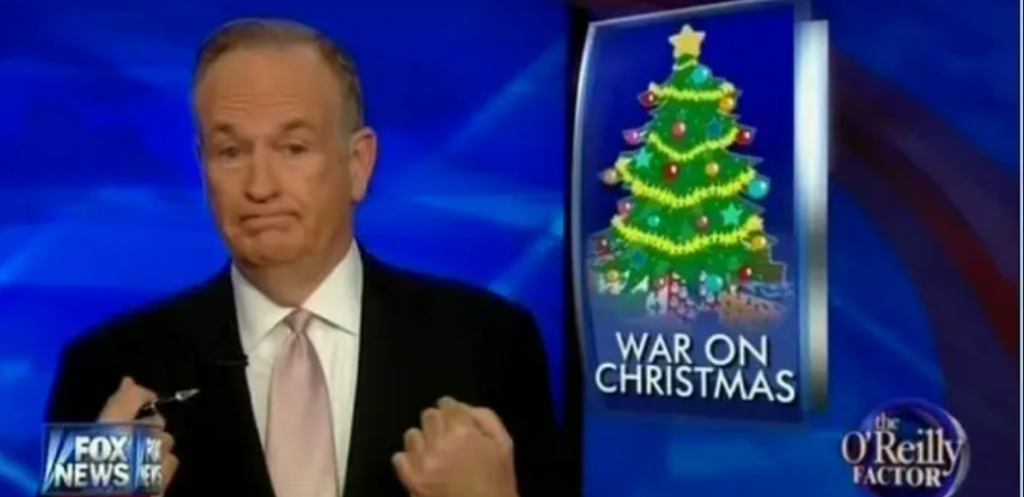

[I’m back to working on a book I started almost ten years ago, that came out of the “Deliberating War” class. I’m hoping for a book that is about 40k words, so twice the length of my two books with The Experiment, but half the length of any of my scholarly books. It starts with “The Debate at Sparta,” goes to this (hence the comment about a previous chapter), moves to wankers in Congress in the 1830s, and then I think the appeasement rhetoric, Hitler’s deliberations with his generals, Falklands, and then metaphorical wars (like the “War on Christmas”). I wanted to post this section for reasons that are probably obvious.]

When I had students read Adolf Hitler’s speech announcing the invasion of Poland, they often expressed surprise—not that he had invaded Poland, but that he bothered to try to rationalize it as self-defense, that he presented Germany as a perpetual victim of aggression. They were surprised because they expected that Hitler wouldn’t try to claim that Germany was a victim, let alone that he was forced into war by others—they thought he would openly warmonger. He had been quite open in Mein Kampf about his plans for German world domination, and he wasn’t the first leader of Germany to plan to achieve European hegemony through war—why claim victim status now?

And I explained that, regardless of their motives or plans or desires, people generally don’t like to see ourselves as exploiting others, or engaged in unjust behavior. And even Hitler needed to maintain the goodwill of a large number of his people—while actual motives might have been a mixture of a desire for vengeance, doing-down the French, relitigating the Great War, making Germany great again, racism and ethnocentrism, German exceptionalism, Germans (just like everyone else) wanted to believe that right and justice were on their side. It’s rare, in my experience, that people explaining why they should go to war (or, as in the case of Hitler and Poland, why he has gone to war) will claim anything other than that they were forced into war, they tried to negotiate their concerns reasonably, and that their actions are sheer self-defense. One of the functions of rhetoric is legitimating a policy decision; in the case of arguing for immediate maximum military action, that position considered most legitimate is self-defense. So, almost everyone claims self-defense. Even the “closing window of opportunity” line of argument for war is (including when used by both sides, as in the Sparta-Athens conflict) an assertion of a sort of “pre-emptive self-defense”—we are not in immediate danger of extermination, but the enemy will exterminate us some day, and this is our best opportunity to prevent that outcome, so it is self-defense to exterminate them.

There is an interesting exception. According to Arrian of Nicomedia (a Greek historian probably writing in the second century AD), in 326 BCE Alexander the Great faced resistance from his army. He was on the Beas River, considering conquering the Indian region just past Hyphasis, but his army was less than enthusiastic. Arrian says, “the sight of their King undertaking an endless succession of dangerous and exhausting enterprises was beginning to depress them,” and they were grumbling. Scholars argue about whether the incident should be properly called a mutiny, but of more interest rhetorically is that the speech that Arrian reports is one of few instances of a genuinely “pro-war” speech, in which the rhetor doesn’t base the case on self-defense.

Alexander begins his speech by observing that his troops seem less enthusiastic than they had been for his previous adventures, and goes on to remind them of how successful those ventures have been.

“[T]hrough your courage and endurance you have gained possession of Ionia, the Hellespont, both Phrygias, Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, Lydia, Caria, Lycia, Pamphylia, Phoenicia, and Egypt; the Greek part of Libya is now yours, together with much of Arabia, lowland Syria, Mesopotamia, Babylon, and Susia; Persia and Media with all the territories either formerly controlled by them or not are in your hands; you have made yourselves masters of the lands beyond the Caspian Gates, beyond the Caucasus, beyond the Tanais, of Bactria, Hyrcania, and the Hyrcanian sea; we have driven the Scythians back into the desert; and Indus and Hydaspes, Acesines and Hydraotes flow now through country which is ours.”

It is an impressive set of accomplishments, but Alexander goes on to make an odd (and highly fallacious) sort of slippery slope argument—since we’ve accomplished so much, he says, why stop now? Is Alexander really proposing to keep conquering until they start losing? If people have gained territory in war, the cognitive bias of loss aversion (we hate to let go of anything once we’ve had it in our grasp—the toddler rule of ownership) means we will go to irrational lengths to keep from losing it, or to get it back. Since that bias will kick in as soon as he stops winning, he is in effect, arguing for endless war. It’s one thing to say that we have to fight till we exterminate a specific threatening enemy, but another to argue for world conquest, for an endless supply of enemies.Yet, that does seem to be his argument: “to this empire there will be no boundaries but what God Himself has made for the whole world.”

He says that the rest of Asia will be “a small addition to the great sum of your conquests,” easily achieved because “these natives either surrender without a blow or are caught on the run—or leave their country undefended for your taking and when we take it.” But, if they stop now, “the many warlike peoples” may stir the conquered areas to revolt. In other words, he has the problem of the occupation (it’s always the occupation). That argument is the closest that he gets to a self-defense argument, and he isn’t claiming that Macedonia faces extinction unless they try to conquer India; he’s saying that they might lose what they’ve gained. And it’s a vexed argument. Are the people in Asia to be feared or not—they seem both easy to conquer, but threats to the Macedonians? Second, and more important, he has established an “ill” (there might be revolt) that isn’t solved by his plan (conquering all of Asia). No matter how much he conquers, unless he conquers the entire world, there will always be a border that has to be defended. And conquering more territory doesn’t make it easier to occupy existing conquered areas.

I mentioned in the previous chapter that the complicated range of options available to one country in regard to provocative action on the part of another tend to get reduced into the false binary of pro- or anti-war. Rhetors engaged in demagoguery do the same thing.

There were rhetors opposed to the Bush plan for invading Iraq who were not opposed to war in general, or even invading Iraq in principle, but they wanted to wait till the action in Afghanistan was completed, or they wanted UN approval, or they wanted to begin with more troops. Yet, they were often portrayed as “anti-war.” Similarly, Alexander’s troops can hardly be called “anti-war”—they’ve spent the last eight years fighting Alexander’s wars. They don’t want this war, at this time.

This tendency to throw people opposed to this war plan into the anti-war bin is ultimately a pro-war move because it makes the issue seem to be war, rather than the specific plan a rhetor is proposing. It isn’t really possible to deliberate about war in the abstract; we can only deliberate about specific wars, and specific plans for those wars. And, since being opposed to war in the abstract is an extreme position, the tendency to describe the problem as pro- v. anti-war puts the harder argument on anyone objecting to this war—they look like they’re pacifists or cowards or they don’t recognize the risks the enemy presents. They can easily be framed as though they are arguing for doing nothing (which is how they’re almost always framed). I’m not saying that the general public should deliberate all the possible options and military strategies—in this chapter I’ll talk about some ways such open deliberation can contribute to unnecessary wars—but that we should remember that it’s rarely (never?) a question of war or not. We have options.

If another country has done something provocative, we can respond with: immediate maximum military response (going to war immediately); careful mobilization of troops, resources, and allies that might delay hostilities (but we fully intend them to happen); limited military response; a show of force intended to improve our negotiating position when we are genuinely willing to go to war; a show of force that we have no intention of escalating into war (a bluff); economic pressures; shaming; nothing. Even the last option isn’t necessarily an anti-war position—it might simply mean that this provocation doesn’t merit war.

But notice that Alexander doesn’t have all those options because the countries he wishes to conquer have done nothing provocative, other than to exist. If there is a legitimate casus belli—that is, if a country has strategic or political goals other than sheer conquest—then negotiation is possible, and the threat of war can add rhetorical weight to one side or another in that negotiation. If conquest is the goal, however, then the “negotiations” are simply determining the conditions of surrender (or, as in the case of the “Melian Dialogue,” allowing the choice between slavery and extermination).

In the case of Hitler, he tried to look like someone who had negotiable strategic and political goals, and he succeeded for quite some time. His rhetoric about the invasion of Poland was part of that rhetorical strategy, of looking as though he didn’t have sheer conquest as his goal, and was simply using negotiating as a way of keeping his window of opportunity open as long as possible. Alexander makes no such move, perhaps because the rhetorical situation meant he wasn’t constrained by the need to establish some kind of legitimacy for his hostilities. His troops didn’t need to be told that this was anything other than a war of conquest. They’d known that for eight years.