A quote attributed to Margaret Mead is going around, which she may or may not have said. People sharing that quote have had various commenters disagree with Mead about her implicit definition of civilization—as far as I can tell, none of them cultural anthropologists or sociologists. (I’ll come back to that.)

While the quote is very badly sourced, it’s possible that she said something along the lines of the quote, since it’s in line with other things she said. And, if she said it, it was not an invitation to debate the distinction between civilized and non-civilized cultures but her attempt to show that distinction is always grounded in the wrong goals. This is, after all, among the scholars who advocated “cultural relativism.” She was never in favor of anthropology as a justification for imperialism. And it often was, and the civilized v. non-civilized binary was crucial to various projects of imperialism and extermination.

When that binary was popular, and (for complicated reasons) I happen to have read a lot of “scholars” and “experts” who endorsed that binary, none of them put their favored cultures in the “non-civilized” category. That’s one sign that a binary is part of a set of paired terms, in which everything good is associated with the in-group, and everything bad is associated with the out-group. The entry from the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences shows why it isn’t a concept much used by scholars (except for understanding rhetorics of exploitation):

“Thus, the significations accruing to civilization have been the following: European/Western; urban and urbane; secular and spiritual; law-abiding and nonviolent (i.e., limited to legalized violence, both within and between states); polished, courteous, and polite; disciplined, orderly, and productive; laissez faire, bourgeois, and comfortable; respectful of private property; fraternal and free; cultured, knowledgeable, and the master of nature. The uncivilized conversely are: non-Western; rural, or worse, savage; idolatrous, fanatical, literalist, and theocratic; unlawful and violent (i.e., given to violence outside juridical procedure); crude or rude; lazy, anarchic, and unproductive; communistic, poor, and inconvenienced or beleaguered; piratical and thievish; fratricidal (or, indeed, cannibalistic) and unfree; uncultured, ignorant, illiterate, superstitious, and at nature’s mercy. Given this stark set of binaries, it is not surprising that the civilizing mission (a related concept that emerged in the nineteenth century) has often been the ideological counterpart of projects of colonial domination and genocide, especially in the non-Western world, but also in the European hinterland and vis-à-vis European minorities and subaltern classes.” “Civilization.” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, edited by William A. Darity, Jr., 2nd ed., vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2008, pp. 557-559. Accessed 29 Nov. 2020.

As an aside, I have to note that I keep telling people that what is kind of a throwaway in Perelman and Olbrecths-Tyteca’s The New Rhetoric is actually crucial to understanding public discourse, especially as that discourse crawls up the ladder of demagoguery: the concept of paired terms. The civilized/non-civilized distinction is a great example of why the notion of paired terms is so useful. For each good term, there is a bad one, and so it reinforces the notion that there are two kinds of groups: good (in-group) and bad (out-group).

But, back to the Mead quote. The whole notion that there is some kind of line between civilized and uncivilized cultures is self-serving nonsense, and that was a point she often made. At the time that Mead was working, it would have been easy to notice that genocidal projects relied on this binary, even when it made no sense (Nazi rhetoric framed Slavs and Jews as uncivilized; genocides of indigenous peoples depended on pretending that they didn’t have organized cultures). And she noticed. There are problems with her research, and she was no saint, but, for her era, she was surprisingly aware of the political uses of cultural anthropology, and she tried to resist some of the nastiest uses.

The groups thrown into the “uncivilized” category were actually wildly different from each other. In other words, the distinction itself is demagogic—it’s saying that the complicated and nuanced world of cultures is really a binary. That binary, which was really just a strategically incoherent us v. them binary, “justified” violence against out-groups–all out-groups. Because this out-group is like that out-group, and that out-group is dangerous, all out-groups are dangerous in all the ways any individual out-group is. That’s what this binary does. The whole project of defining a culture as civilized or not is about rationalizing the exploitation, oppression, and/or extermination of some group.

There are two other points I want to make. First, if you pay attention to pro-GOP rhetoric, then you might be aware that they try to employ this same set of paired terms against “liberals.” If, like me, you pay attention to pro-GOP talking points, then you can see that they frame “liberals” (just as much a phantasmagoric construction as “Jews”) as (from the entry above): “non-Western; […] fanatical […] violent (i.e., given to violence outside juridical procedure); crude or rude; lazy, anarchic, and unproductive; communistic, poor, and inconvenienced or beleaguered; piratical and thievish; fratricidal (or, indeed, cannibalistic) and unfree.”

You might notice that I’ve removed “rural, or worse, savage; idolatrous” “literalist, and theocratic” “uncultured, ignorant, illiterate, superstitious, and at nature’s mercy.” Pro-GOP is either silent on those characteristics or actively promotes them as virtues.

And that bring me to the fourth point, and the most complicated.

Many years ago, I was talking with someone who hadn’t taken a history class since high school, but who, on the basis of a paper he wrote in high school, thought he was an expert on Hitler, whose opinion about Hitler was as valid as any actual scholar. Once, in front of a colleague who was a devotee of Limbaugh, I said, “Were I Queen of the Universe, no one could make a Hitler analogy without citing two scholars in support,” and he said, “Oh, so you think common people should be silenced.”

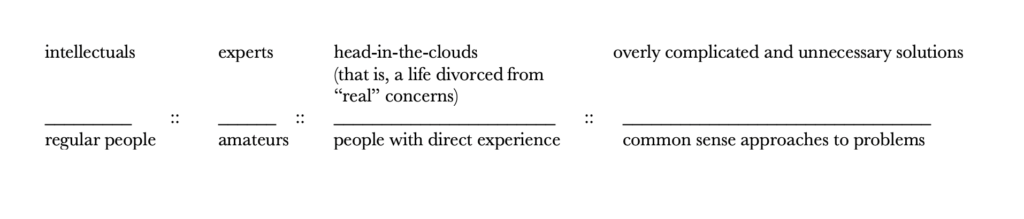

I was speechless. (That doesn’t often happen.) He was projecting his own tendency to think in binaries onto me—knowledge is either lay (true) or expert (head in the sky). That’s a Limbaugh talking point, but it had little to do with what I was saying. I was saying that lay claims about Hitler that were valid could be validated by appealing to experts. I didn’t (and don’t) see a binary of expert v. lay knowledge. After all, a lot of experts endorsed the notion of civilized v. non-civilized cultures. Experts aren’t always right, and they don’t always agree. If no expert supports a claim about Hitler (and there are lots of popular claims about Hitler that no expert supports, such as the notion that he was Marxist or even left-wing) then it’s probably a bad claim.

In addition, what does it mean to have lay knowledge of Hitler? This isn’t an issue for which there is direct experience v. expert (i.e., mediated) knowledge because I doubt there is anyone alive who had direct experience of Hitler. It’s all mediated. It’s all about what people have told us. All we have is what we have been told by teachers, articles we read, papers we wrote in high school. The reason this point matters is that it means that privileging lay knowledge on the grounds that it is more direct (less mediated) is nonsense.

If we acknowledge it’s mediated then we can talk about what mediates it. In other words, cite your sources, and then we can argue about your sources.

If we think about it this way—how good are your sources of information—then we can have a better argument about argument.

We aren’t in a world in which experts are right and non-experts are always wrong or vice versa. We’ve never been in that world because the whole project of responsible scholarship is not about being right, but about making the argument that looks the most right given the evidence we’ve got at this moment.

And here we’re back to people arguing that something that Mead may or may not have said is wrong because, although they aren’t cultural anthropologists, they have beliefs.

They can have those beliefs. And just because Mead has degrees they don’t doesn’t mean they’re wrong. They can engage in argumentation with Mead all they want (and there are a lot of reasons to engage in argumentation with Mead), but flicking Mead away because of something they assert to be true because it’s what they have been told without trying to understand why Mead (might have) said what she did or whether their sources were reliable is exactly what is wrong with our public discourse.

Showing that Mead is wrong in her definition of civilization requires understanding what she (might have) meant in that definition. She almost certainly meant that the civilized/non-civilized binary is nonsense, so saying her position was wrong because the civilized/non-civilized division should have been placed elsewhere doesn’t show she was wrong. It shows she was right.