April 26, 1933, the British Ambassador to Germany (Horace Rumbold) wrote a long (5k words) telegram about Hitler. It was not only prescient about Hitler’s plans and strategies, but smart about authoritarianism. What follows are some excerpts.

The Chancellor has been busy gathering all the strings of power into his hands, and he may now be said to be in a position of unchallenged supremacy. The parliamentary regime has been replaced by a regime of brute force, and the political parties have, with the exception of the Nazis and Nationalists, disappeared from the arena. For that matter Parliament has ceased to have any raison d’etre. The Nazi leader has only to express a wish to have it fulfilled by his followers.

Hitherto I have dealt in despatches with the internal changes and the events of the moment. Now that Hitler has acquired absolute control, at any rate till the 1st April, 1937, it may be advisable to consider the uses to which he may put his unlimited opportunities during the next four years. The prospect is disquieting, as the only programme, apart from ensuring their own stay in office, which the Government appear to possess may be described as the revival of militarism and the stamping out of pacifism. The plans of the Government are far-reaching, they will take several years to mature and they realise that it would be idle to embark on them if there were any danger of premature disturbance either abroad or at home. They may, therefore, be expected to repeat their protestations of peaceful intent from time to time and to have recourse to other measures, including propaganda, to lull the outer world into a sense of security.

The new regime is confident that it has come to stay. At the same time it realises that the economic crisis which delivered Germany into its hands is also capable of reversing the process. It is, therefore, determined, to leave no stone unturned in the effort to entrench itself in power for all time. To this end it has embarked on a programme of political propaganda on a scale for which there is no analogy in history. Hitler himself is, with good reason, a profound believer in human, and particularly German, credulity. He has unlimited faith in propaganda. In his autobiography he describes with envy and admiration the successes of the Allied Governments, achieved by the aid of war propaganda. He displays a cynical and at the same time very clear understanding of the psychology of the German masses. He knows what he has achieved with oratory and cheap sentiment during the last fourteen years by his own unaided efforts. Now that he has the resources of the State at his disposal, he has good reason to believe that he can mould public opinion to his views to an unprecedented extent.

Dr. Goebbels is engaged on a two-fold task, to uproot every political creed in Germany except Hitlerism and to prepare the soil for the revival of militarism. The press has been delivered into his hands, and he has declared that it is his intention “to play upon it as on a piano.”

The outlook for Europe is far from peaceful if the speeches of Nazi leaders, especially of the Chancellor, are borne in mind. The Chancellor’s account of his political career in Mein Kampf contains not only the principles which have guided him during the last fourteen years, but explains how he arrived at these fundamental principles. Stripped of the verbiage in which he has clothed it, Hitler’s thesis is extremely simple. He starts with the assertions that man is a fighting animal; therefore the nation is, he concludes, a fighting unit, being a community of fighters. Any living organism which ceases to fight for its existence is, he asserts, doomed to extinction. A country or a race which ceases to fight is equally doomed. The fighting capacity of a race depends on its purity. Hence the necessity for ridding it of foreign impurities. The Jewish race, owing to its universality, is of necessity pacifist and internationalist. Pacifism is the deadliest sin, for pacifism means the surrender of the race in the fight for existence. The first duty of every country is, therefore, to nationalise the masses: intelligence is of secondary importance in the case of the individual; will and determination are of higher importance. The individual who is born to command is more valuable than countless thousands of subordinate natures. Only brute force can ensure the survival of the race. Hence the necessity for military forms. The race must fight; a race that rests must rust and perish. The German race, had it been united in time, would now be master of the globe to-day. The new Reich must gather within its fold all the scattered German elements in Europe. A race which has suffered defeat can be rescued by restoring its self-confidence. Above all things, the army must be taught to believe in its own invincibility. To restore the German nation again ” it is only necessary to convince the people that the recovery of freedom by force of arms is a possibility.”

Intellectualism is undesirable. The ultimate aim of education is to produce a German who can be converted with the minimum of training into a soldier. The idea that there is something reprehensible in chauvinism is entirely mistaken. ” Indeed, the greatest upheavals in history would have been unthinkable had it not been for the driving force of fanatical and hysterical passions. Nothing could have been effected by the bourgeois virtues of peace and order. The world is now moving towards such an upheaval, and the new (German) State must see to it that the race is ready for the last and greatest decisions on this earth ” (p. 475, 17th edition of Mein Kampf). Again and again he proclaims that fanatical conviction and uncompromising resolution are indispensable qualities in a leader.

Foreign policy may be unscrupulous. It is not the task of diplomacy to allow a nation to founder heroically but rather to see that it can prosper and survive. There are only two possible allies for Germany—England and Italy (p. 699). No country will enter into an alliance with a cowardly pacifist State run by democrats and Marxists. So long as Germany does not fend for herself, nobody will fend for her. Germany’s lost provinces cannot be gained by solemn appeals to Heaven or by pious hopes in the League of Nations, but only by force -of arms (p. 708).

Germany must not repeat the mistake of fighting all her enemies at once. She must single out the most dangerous in. turn and attack him with all her forces ” (p. 711). “I t is the business of the Government to implant in the people feelings of manly courage and passionate hatred.” The world will only “cease to be anti-German when Germany recovers equality of rights and resumes her place in the sun.

Hitler admits that it is difficult to preach chauvinism without attracting undesirable attention, but it can be done. The intuitive insight of the subordinate leaders can be very helpful. There must be no sentimentality, he asserts, about Germany’s foreign policy. To attack France for purely sentimental reasons would be foolish. What Germany needs is an increase in territory in Europe. Hitler even argues that Germany’s pre-war colonial policy must be abandoned, and that the new Germany must look for expansion to Russia and especially to the Baltic States. He condemns the alliance with Russia because the ultimate aim of all alliances is war. To wage war with Russia against the West would be criminal, especially as the aim of the Soviets is the triumph of international Judaism.

A number of the clauses of the original twenty-five-point programme have been abandoned as Utopian or out of date, but the campaign against the Jews goes to show that Hitler will only yield to energetic opposition even on comparatively unimportant points of policy. The brutal harshness with which he has overwhelmed his opponents of the Left and the ruthlessness with which he has muzzled the press are disquieting signs.

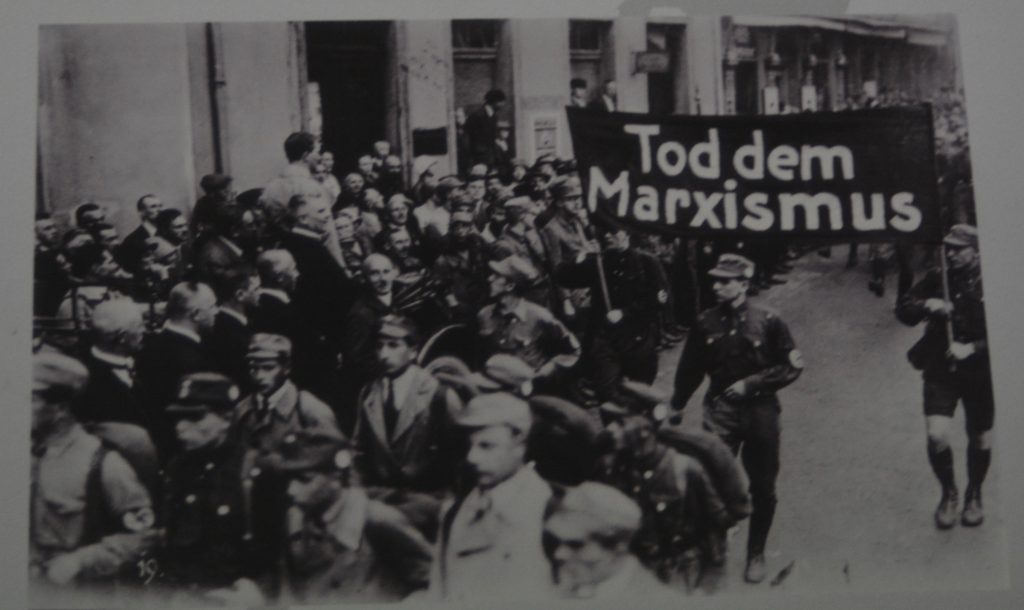

Not only is it a crime to preach pacificism or condemn militarism but it is equally objectionable to preach international understanding, and while politicians and writers who have been guilty of the one have actually been arrested and incarcerated, those guilty of the other have at any rate been removed from public life and of course from official employment. The Government are openly hostile to Marxism on the ground that it savours of internationalism, and the Chancellor in his electoral speeches has spoken with derision of such delusive documents as peace pacts and such delusive ideas as the “spirit of Locarno.” Indeed, the foreign policy which emerges from his speeches is no less disquieting than that which emerges from his memoirs. Even when allowance is made for the exaggerations attendant upon a political campaign, enough remains to make it highly probable that rearmament and not disarmament is the aim of the new Germany.

Representative government has been overthrown. Parliament has to all intents and purposes been abolished. A campaign of terror instituted by the authorities has not failed to have its effect on Democrats, Socialists and Communists alike. It is doubtful whether any real resistance would now be offered to a return to conscription. Still more serious is the fact that the resumption of the manufacture of war material by the factories can be undertaken to-day with much less fear of detection or denunciation than heretofore. Owing to the abolition of the press of the Left and the exemplary punishment of traitors and informers, it will be much easier in future to observe secrecy in the factories and workshops. I cannot help thinking that many of the measures taken by the new Government of recent weeks aim at the inculcation of that silence, or “Schwiegsamkeit,” which Hitler declares in his memoirs to be an essential to military preparations. In the introduction to my annual report last year I stated (paragraph 27) that militarism in the pre-war sense, as exemplified by the Zabern incident, no longer existed in Germany. I wrote (paragraph 29) that there had been a revival of nationalism, that nationalism, was not synonymous with militarism, but I added that, ” should nationalist feeling in Germany become exacerbated, it might well lead to militarism.” The present Government have, I fear, exacerbated national feeling, with the results which I anticipated.

Indeed, the political vocabulary of national socialism is already saturated with militarist terms. There is incessant talk of onslaughts and attacks on entrenched positions, of political fortresses which have been stormed, of ruthlessness, violence and heroism. Hitler himself has proclaimed that Germany is now to enter upon a ” heroic ” age, in which the individual is to count for nothing, and the weal of the State for everything.

They [German forces] have to rearm on land, and, as Herr Hitler explains in his memoirs, they have to lull their adversaries into such a state of coma that they will allow themselves to be engaged one by one. It may seem astonishing that the Chancellor should express himself so frankly, but it must be noted that his book was written in 1925, when his prospects of reaching power were so remote that he could afford to be candid. He would probably be glad to suppress every copy extant to-day. Since he assumed office, Herr Hitler has been as cautious and discreet as he was formerly blunt and frank. He declares that he is anxious that peace should be maintained for a ten-year period. What he probably means can be more accurately expressed by the formula : Germany needs peace until she has recovered such strength that no country can challenge her without serious and irksome preparations. I fear that it would be misleading to base any hopes on a return to sanity or a serious modification of the views of the Chancellor and his entourage. Hitler’s own record goes to show that he is a man of extraordinary obstinacy. His success in fighting difficulty after difficulty during the fourteen years of his political struggle is a proof of his indomitable character.

Herr von Papen, speaking in Breslau a few weeks ago, stated that Hitlerism in its essence was a revolt against the Treaty of Versailles. The Vice-Chancellor for once spoke unvarnished truth. Hitlerism has spread with extraordinary rapidity since the 5th March, and those who witnessed the celebration of Hitler’s birthday a few days ago must have been impressed by the astonishing popularity of the new leader with the masses. So far as the ordinary German is concerned, Hitler has certainly restored something akin to self-respect, which has been lacking in Germany since November 1918. The German people to-day no longer feel humiliated or oppressed. The Hitler Government have had the courage to revolt against Versailles, to challenge France and the other signatories of the treaty without any serious consequences. For a defeated country this represents an immense moral advance. For its leader, Hitler, it represents overwhelming prestige and popularity. Someone has aptly said that nationalism is the illegitimate offspring of patriotism by inferiority complex. Germany has been suffering from such a complex for over a decade. Hitlerism has eradicated it, but only at the cost of burdening Europe with a new outbreak of nationalism.

You have minor OCR errors – “to-clay” for example.