[This is from a book I’m writing about how we deliberate about war]

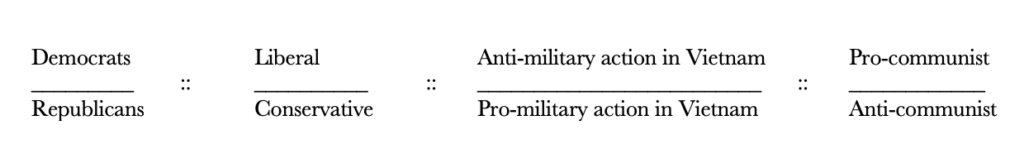

In this book I’ve emphasized “paired terms” because (too) much public discourse presumes that issues can be thought of in terms of a set of associations and opposition as though: 1) those characteristics are necessarily associated or opposed, and 2) are necessarily epitomized in the association/opposition of liberal v. conservative, democrat/republican, and 3) these relationships are causal. That is, we too often talk as though Martin Luther King opposed the Vietnam War because he was liberal, and liberals opposed the Vietnam War because of their liberalism. This way of thinking about politics depoliticizes public discourse, in the sense that we don’t argue about whether, for instance, the policies regarding Vietnam are sensible, likely to get a good outcome, worth the costs, and other policy issues—instead, we argue (or, more accurately, fling assertions) about whether “liberals” or “conservatives” are better people. The false assumption is that, if we can prove that our group is good (or that the out-group is bad), we have thereby proven that our policies are good. That way of thinking about politics in terms of associations and oppositions is false at every step, and the public discourse about Vietnam exemplifies how inaccurate and damaging it is to displace policy argumentation with paired terms.

For instance, we now use the term “conservative” as though it were interchangeable with “Republican,” even when the Republican Party advocates a policy that is a striking violation with past practices (such as Romneycare, the adoption of preventive war in regard to Iraq, the level of governmental surveillance allowed by the USAPATRIOT Act ). Many people use the term “liberal” as though it were interchangeable with “democratic socialist,” “progressive,” and “communist” (when those are four different political philosophies). Democrats are not consistently “liberal,” and Republicans are not consistently “conservative.” In fact, it is simply not possible to define either “liberal” or “conservative” as a political philosophy that either the Democrats or Republicans consistently pursue in terms of policies—both parties advocate small government, big government, low taxes, high taxes, military intervention, states’ rights, federalism, and so on at different points, for different reasons, and generally because of short-term election strategies. Sometimes one party takes a stance simply because it is the opposite of what the other party is advocating—as when the GOP flipped on Romneycare. This observation is not a criticism of either party—that’s what political parties do–, but it is a criticism of thinking that partisanship is an intelligent substitution for policy argumentation.

Martin Luther King and Henry Steele Commager criticized US policies in regard to Vietnam, and both did so from what might usefully be called a “liberal” and Christian perspective, both believing that American foreign policy had to be grounded in moral principles. Hans Morgenthau, conservative, Jewish, and a “realist” in regard to international relations, was also a severe critic of American policies in Vietnam, and on April 18, 1965, The New York Times published a long editorial he wrote in which he argued that, while he appreciated a recent statement of LBJ about Vietnam, on the whole, he thought that “the President reiterated the intellectual assumptions and policy proposals which brought us to an impasse and which make it impossible to extricate ourselves.”

Although Morgenthau had a very different philosophical perspective from either HSC or MLK, his criticisms of American policies in Vietnam had some overlap with theirs. While he agreed that China should be contained, he argued that it was a wrongheaded fantasy to think that it could be contained in the same way that the USSR had been in Europe–that is, through “erecting a military wall at the periphery of her empire.” Like HSC and MLK (and as even Robert McNamara would later admit was true), he insisted that the Vietnam situation was a civil war, not “an integral part of unlimited Chinese aggression.” Ho Chi Minh “came to power not courtesy of another Communist nation’s victorious army but at the head of a victorious army of his own.” Ho Chi Minh had considerable popular support, whereas Diem did not, and therefore this was not a military, but a political, problem. Morgenthau argued that, “People fight and die in civil wars because they have a faith which appears to them worth fighting and dying for, and they can be opposed with a chance of success only by people who have at least as strong a faith.” Supporters of Diem did not have at least a strong a faith because Diem’s policies resulted in his being unpopular (“on one side, Diem’s family, surrounded by a Pretorian guard; on the other, the Vietnamese people”). Morgenthau pointed out that trying to treat such situations in a military way–counter-insurgency–had not worked. The French tried it in Algeria and Indochina (i.e., Vietnam), and it didn’t work, and it wasn’t working for the US in Vietnam. Like HSC and MLK, he emphasized that Diem (and the US, by supporting Diem) had violated the Geneva agreement, especially in terms of refusing to have an election—a refusal that was an open admission that communism was not imposed on an unwilling populace, but a popular policy agenda (he notes, largely because of land reform).

Unlike HSC and MLK, Morgenthau spelled out a plan that went beyond simply negotiating with North Vietnam. His plan had four parts:

(1) recognition of the political and cultural predominance of China on the mainland of Asia as a fact of life; (2) liquidation of the peripheral military containment of China; (3) strengthening of the uncommitted nations of Asia by nonmilitary means; (4) assessment of Communist governments in Asia in terms not of Communist doctrine but of their relation to the interests and power of the United States.

In other words, the US should be prepared to ally itself with communist regimes, as long as they were hostile to China. This plan was similar to the policy the US justified as “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”–how we rationalized supporting unpopular authoritarian regimes with appalling human rights records rather than allow elections that might lead to socialist or communist (even if democratic) regimes–but with a more realistic assessment of the varieties of communism and the possible benefits of those alliances. As Morgenthau says, “In fact, the United States encounters today less hostility from Tito, who is a Communist, than from de Gaulle, who is not.”

Just to be clear: Morgenthau had no sympathy for communism. His argument that we should ally ourselves with some communist regimes was, as I said, exactly the same one used for rationalizing our alliances with authoritarian–even fascistic–regimes. His argument that communists should be included in the group that might be the enemy of our enemies was grounded in realism. Realism, as a political theory, values putting the best interests of the nation above “moral” considerations, and strives to separate moral assessments of the “goodness” of allies from their potential utility to the US. We were, after all, closely allied with Israel, Sweden, and various other highly socialistic countries; why not add North Vietnam to that list, as long as it would be an ally?

If we think about the point of public discourse as debating various reasonable arguments, rather than a realm in which we will strive to silence all other points of view, then his is an argument that should be considered. Since support for Diem was grounded in the assumption that we should tolerate mass killings, corruption, incompetence, and authoritarianism if the regime is useful to the US, why not try to assess utility without assuming that an unpopular and incompetent anti-Chinese anti-communist is necessarily and inevitably more useful than a competent, popular, anti-Chinese communist?

Because of paired terms. Because, as Morgenthau says, public discourse, and especially the PR about how Vietnam was being handled, was based in an obviously flawed binary:

It is ironic that this simple juxtaposition of “Communism” and “free world” was erected by John Fuster Dulles ‘s crusading moralism into the guiding principle of American foreign policy at a time when the national Communism of Yugoslavia, the neutralism of the third world and the incipient split between the Soviet Union and China were rendering that juxtaposition invalid.

After all, Nixon decided that China could be treated as an ally–why not North Vietnam? In other words, the foaming-at-the-mouth anti-communism was an act (or, as Morgenthau said, PR); it wasn’t grounded in a consistent set of criteria of assessment utility to the US, even about shared enemies. Morgenthau’s point was that we shouldn’t be alternately moralist and realist, and that is what American foreign policy was—“realist” (that is, thinking purely in terms of utility) when it came to authoritarian governments, but “moralist” when it came to self-identified “communist.”

Whether we should be more consistent about those criteria is an interesting argument, and Morgenthau makes the argument for a more consistent approach to other countries from a coherent realist position. I don’t agree with Morgenthau (I think it’s unrealistic, in a different sense of the term, to believe that power politics is amoral), but even I will say it’s an argument worth making, debating, and considering. To say that an argument is worth being taken seriously is not to say we think it’s true, but it’s plausible.

Defenders of LBJ’s policies neither debated nor refuted his argument. Instead, they shifted the stasis to Morgenthau’s motives and identity, pathologizing him, misrepresenting his arguments, and depoliticizing debate about Vietnam. They shifted the stasis away from defending LBJ’s Vietnam policies to whether Morgenthau was a good person whose view should be considered.

On April 23, 1965, Joseph Alsop responded (sort of) to Morgenthau’s argument in an editorial in the Los Angeles Times called “Expansionism Is a Continuing Theme in the History of China.”

In rhetorical terms, Morgenthau’s argument was a “counter-plan.” Morgenthau agreed with the goal of constraining China, but argued that the current strategy was an ineffective means of achieving that goal. Thus, a reasonable response to Morgenthau’s argument would argue that these means (a military response in Vietnam supporting the unpopular Diem regime) are likely to work in these conditions. That wasn’t Alsop’s response. He characterized Morgenthau’s argument as an argument for appeasing China and letting it “gobble their neighbors at will, even though their neighbors happen to be our friends and allies.” Morgenthau never argued for allowing China to gobble up other countries; he argued that the current American strategy for trying to stop China was ineffective. Alsop was not an idiot; he knew what Morgenthau was arguing. He chose to misrepresent it.

And he chose to take swipes along the way at professors who don’t really know what they’re talking about—as though being a journalist makes someone more of an expert on foreign policy?

Alsop’s argument, in other words, never responded to Morgenthau’s, instead attributing to Morgenthau a profoundly dumb argument that had nothing to do with what he’d actually said. Alsop’s argument wouldn’t work with anyone who’d read Morgenthau’s argument, but it would work with someone who already believed that the only legitimate position in regard to Vietnam was the one advocating a military solution—that is, people unwilling to engage in argumentation about their policy preferences, who instead believed that the way to think about policy option is good (us) v. evil (every other position).

McNamara—the architect of the Vietnam War–would later decide that people like Morgenthau, MLK, and HSC were right. It was a civil war, Minh had considerable popular support, communism was not being forced on a completely unwilling populace by the Chinese, the situation was not amenable to a military solution. There were over 50,000 US deaths in the Vietnam conflict after Morgenthau made his argument. If even McNamara came around to Morgenthau’s position, doesn’t that suggest it was a position worth taking seriously in 1965?

I’m not saying Morgenthau’s policy should have been adopted in 1965; I’m saying it should have been argued.

Alsop (and others) did their best to ensure it wouldn’t be argued by making sure their audience never heard it, and instead heard a position too dumb to argue. And that is what partisans all over the political spectrum do—take all the various, nuanced, and sometimes smart critics of their position and homogenize them into the dumbest possible version, and they can count on an audience that never takes the time to figure out if they’re reading straw man versions of the various possible oppositions and critics. There are two lessons from Morgenthau’s treatment by people like Alsop. First, don’t be that audience.

We would never think we have been heard if people have only heard what our enemies say about us. Why should we think we have heard what others have to say if we only listen to what their enemies say about them?

Second, Morgenthau was conservative. He was a critic of how LBJ, a liberal, was handling the Vietnam conflict. MLK was liberal. He was a critic of how LBJ, a liberal, was handling the Vietnam conflict. Paired terms are wrong. It isn’t an accurate map of how beliefs and political affiliations and policies actually work. Good people endorse bad policies; our political options are not bifurcated into liberal v. conservative; being “conservative” (or atheist, Christian, democratic socialist, Jewish, liberal, libertarian, Muslim, progressive, reactionary, realist) doesn’t mean you necessarily endorse one of only two options in terms of policy agenda.

We need to argue policies.

McGeorge Bundy “debated” Han Morgenthau on CBS in June of 1965, and the scholar of rhetoric Robert Newman wrote a critique of Bundy’s rhetoric in the journal Today’s Speech. He said, and it’s worth quoting at length:

Much of the profound disquiet about Viet Nam policy results from the increasing and systematic distortion of official news. There are, of course, especially in academic circles, the “doves” who want peace and noninvolvement even if this means communist control of some distant land. Bundy was not talking to them; nor is Morgenthau one of them. But even those of us who are inclined to be “hawks” are not anxious to back losers. We have had enough of this with Chiang Kai-Shek. We are afraid that Viet Nam, also, is the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time. And we are tired of being lied to.

Newman goes on to list the post-war intelligence debacles of the CIA—the Bay of Pigs, wishful thinking about what the Chicoms would do in the Korean conflict, bad predictions about the Viet Cong in 1961. He mentions Secretary Rusk claiming in 1963 that the “strategic hamlet program was producing excellent results” when, actually, “this whole operation was a disastrous failure,” and, well, many other, if not outright lies, then instances of unmoored optimism that were quickly and unequivocally exposed as false. Newman concludes about Bundy’s treatment of Morgenthau, “Thus i[n] a situation where what was desperately needed was reinforcement of the shattered credibility of the government which Mr. Bundy represents, we got only ad hominem attack on a critical professor.”

And that is the problem with our political discourse, all over the political spectrum. That’s all we get, Two Minutes Hate about “the” opposition. What we need is policy argumentation. If you don’t read primary opposition sources, and you only rely on in-group sources for what “they” believe, you’re no better off than fans of Alsop.