If, like me, you have spent your life arguing with assholes, then you find yourself in the same kind of argument. It doesn’t matter if they’re Stalinists, Maoists (my least favorite interlocutors), crude Freudians, raw food for dog cultists, or, now, anti-maskers. Assholes aren’t restricted to any one place on the political spectrum, or even necessarily restricted to the “political” spectrum at all. By “asshole,” I don’t mean people who are unpleasant or aggressive, but people who can’t defend their position rationally, and feel no obligation to do so. Although they can’t defend their position rationally, they are certain that they are right because 1) they can find data to support them, and 2) they feel certain that they’re right.

In general, you find someone like this on every issue, but there are some issues on which everyone is like this. What I’ve found by drifting around and trying to read the best anti-mask/anti-vaccine posts is that none of them can defend their position rationally, so those are in that latter category.

When pushed to support their case rationally (e.g, hold all data to the same standards, have an internally consistent argument, be able to name the data that would cause them to change their mind, represent opposition arguments fairly, avoid fallacies) they get mad. They get mad if asked to support their case rationally, and they try to shift the burden of proof–their position is true because it can’t be proven wrong. Once again, that isn’t a rational argument.

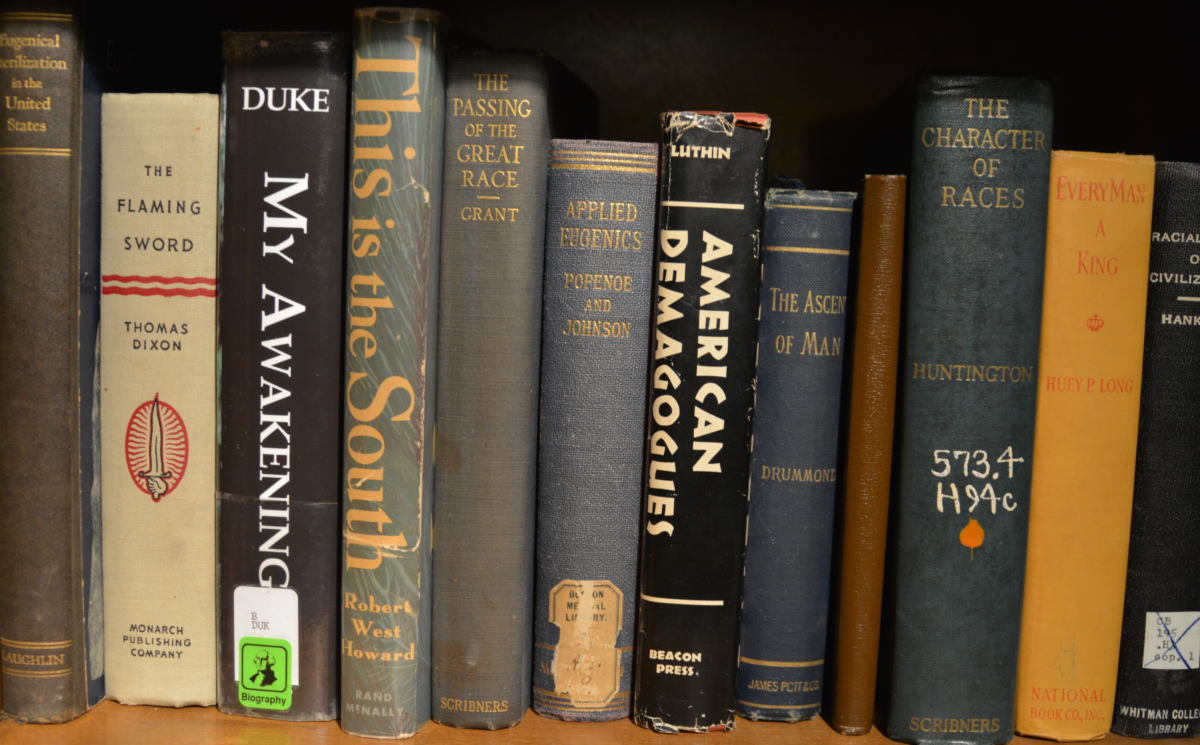

Making a rational argument isn’t about your tone, whether you have evidence, or whether it feels true to you–anyone can cherrypick the data to make any case. I learned this watching someone present a lot of data that Stephen King and Richard Nixon conspired together to kill John Lennon–lots of data, all of it cherrypicked, none of it rationally related to the overall claim. That guy had done too much speed, and ended up in jail for stalking Stephen King. Having data that to you proves a point doesn’t mean you have a rational argument. You might have done too much speed.

For this post, I’ll talk about the strongest argument I’ve seen against masks (since it cited a study). And the first point I’ll make is that no anti-mask or anti-vax person has read this far. They do not read anything that might complicate, let alone disconfirm, their point of view. So, they fail the absolutely lowest level of having a rational position–being able to engage the smartest opposition. They don’t even engage dumb oppositions. They run away from opposition information the way I run away from snakes. It isn’t rational, but it’s what I do. If you refuse to read opposition arguments (and not what your in-group tells you are the opposition arguments) then you don’t have a rational position–it doesn’t matter what the issue is.

Anti-maskers often claim that 1) masks are ineffective, and 2) they reduce oxygen intake and exhalation of carbon monoxide. The “and” is important. On its face (prima facie) this is an irrational argument. Both of those claims cannot be true at the same time. If masks significantly inhibit inhalation and exhalation, then they would definitely inhibit the spread of and threat of infection from covid.

I recently pointed this out, and someone responded by citing this study.

This is typical. They found a study that says that masks do inhibit inhalation and exhalation. That study doesn’t solve the basic contradiction–if masks are extremely effective at restricting inhalation/exhalation, they are extremely effective at preventing the spread of COVID.

But, let’s set aside that contradiction (one present in the cited study). I’m not an epidemiologist, but I am an expert in argumentation, and one of the most salient aspects of an irrational position is cherry-picking data. (As I said, this is true of irrational positions on all issues.)

The most prominent characteristic of an irrational position–whether it’s about masks, tax breaks, raw food for dogs, my desire for a camper, whether your boss is a jerk– is that it’s about finding data to support our position, and not taking one step above, and thinking about our position in terms of whether it relies on premises and data you’d think valid if they led to opposite conclusions.

Irrational people on the internet find a study that supports what they believe, on the basis of the abstract. (They reject all studies that don’t support them, also based on the abstract.) I read the study. The person who cited it obviously didn’t. (This is typical.) But, if one study proves you right, then one study proves you wrong.

And this study didn’t even prove them right. Most of the study looked at research regarding N95 mask use among medical workers. As the study says, “Thirty papers referred to surgical masks (68%), 30 publications related to N95 masks (68%), and only 10 studies pertained to fabric masks (23%).” The study says that surgical and N95 masks are effective for preventing the spread of COVID (see especially pages 20-21), so the person cited a study as an authority that contradicts the anti-mask talking point. That’s also typical of someone who can’t support their case rationally (because they don’t read the studies they cite).

Most important, the negative consequences were associated with N95 masks, not fabric ones. So, how many people out in public are wearing N95 masks? I asked the person who posted this study what she thought of the following paragraph. She never responded. Also typical of someone defending a position irrationally.

“In addition, we found a mathematically grouped common appearance of statistically significant confirmed effects of masks in the primary studies (p < 0.05 and n ≥ 50%) as shown in Figure 2. In nine of the 11 scientific papers (82%), we found a combined onset of N95 respiratory protection and carbon dioxide rise when wearing a mask. We found a similar result for the decrease in oxygen saturation and respiratory impairment with synchronous evidence in six of the nine relevant studies (67%). N95 masks were associated with headaches in six of the 10 studies (60%). For oxygen deprivation under N95 respiratory protectors, we found a common occurrence in eight of 11 primary studies (72%). Skin temperature rise under masks was associated with fatigue in 50% (three out of six primary studies). The dual occurrence of the physical parameter temperature rise and respiratory impairment was found in seven of the eight studies (88%). A combined occurrence of the physical parameters temperature rise and humidity/moisture under the mask was found in 100% within six of six studies, with significant readings of these parameters (Figure 2).”

To be clear, the study expresses skepticism about mask-wearing generally, but their meta-research doesn’t support that skepticism. When they get to the part of the argument in which they want to say that wearing masks is harmful, the authors abandon their meta-research (because meta-research wouldn’t support their position) and start citing various individual studies that suggest that fabric masks might not be very effective. So, on the whole, the study shows that fabric masks might not be effective but aren’t harmful, and N95 are effective but might be harmful. Not an argument against wearing masks.

And the “harms” the study identifies for the N95 masks are far preferable to the harms of getting COVID. When it gets to the harms of fabric masks, the study starts arguing syllogistically, and seems to be assuming that people are not washing their masks. (Yeah, if you wear a fabric mask and don’t wash it on a daily basis, you’re likely to get acne. If this is news to you, we need to talk about your underwear.)

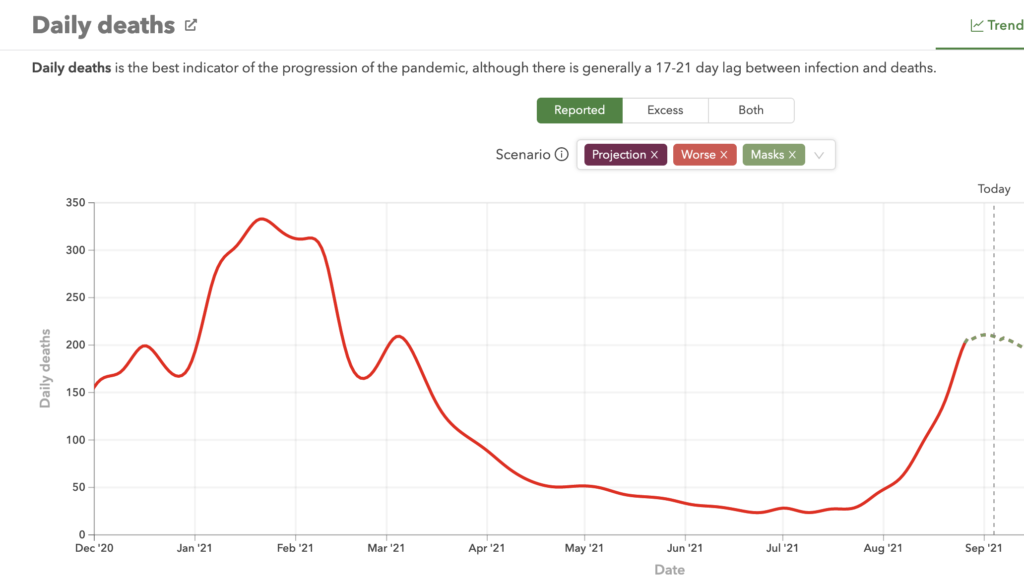

I could make other points about the study, such as that they didn’t include the variable of social distancing, none of the authors appears to be an epidemiologist, and it isn’t clear that anyone is a statistician, but the most important point is that the study as a whole doesn’t support the claim that masks are useless, let alone that masks are useless and harmful. What it does show is something that experts have been saying for a while: wearing a fabric mask (especially if, as the authors assume, one keeps wearing a fabric mask without washing it) is not a guarantee in and of itself (helllooooo, social distancing!) and might have problems. That is something that research has been saying for at least a year. Wearing a mask and engaging in social distancing is probably a good strategy:

“Evidence for efficacy of face masks against the first SARS virus, SARS-CoV-1, implies that they may be effective against the current outbreak of SARS-Cov-2 virus. This is important as mathematical modeling suggests that even small reductions of in transmission rates can make a large difference over time, potentially slowing the pace of viral pandemics and limiting their spread. Perhaps the strongest argument for the use of masks is that countries with early adoption of masks have tended to see flatter pandemic curves, even without strict nationwide lockdowns.[…] Improvised masks are less effective than medical masks, but may provide better protection than nothing at all.”

I picked this study because it’s over a year old, and pretty typical of what studies of fabric masks had and have been saying for a while. It also includes the issue of social distancing–a variable the anti-mask study didn’t include. This study says that a person wearing a non N95 mask can still expel droplets 20 cm. (That’s about eight inches.) So, social distancing is an important factor. This study doesn’t support a claim that masks are guaranteed to prevent infection, just as seat belts won’t magically prevent a person from injuries in a car wreck (and a person might be injured by the seat belt, albeit less injured than if they weren’t wearing one), but it does give good reason to think that wearing a mask, coupled with social distancing, will reduce COVID infection rates.

The anti-masker position is irrational because its advocates can’t put forward arguments that meet the lowest standards of a rational argument. They fail at the most basic level of: 1) having an internally consistent argument; 2) engaging the best opposition arguments; 3) holding themselves and their oppositions to the same standards of proof; 4) avoiding major fallacies.

Here’s how an anti-masker or anti-vaxxer could prove me wrong: identify the data that would cause you to admit you’re wrong; put forward an internally consistent argument that holds all data to the same standards; engage the best opposition arguments.

Beleaguered by facts (99.9% of covid hospitalisations are unvaccinated), increasingly the response of anti-vaxxers is, “I don’t care what you have to say. Leave me alone.”