In Deliberate Conflict I ridiculed a particular kind of assignment as not teaching argumentation. Since I’m retired, I can make the stronger argument: this kind of assignment teaches students to think they know what good argumentation is, when it it isn’t teaching argumentation at all. It’s like telling students you’re teaching them how to play chess, when you give good grades to students who tip over the board. It does so because it puts teachers into a false dilemma when it comes to grading terrible arguments.

Here’s the assignment prompt:

Write a well-organized five page argument for a policy about which you care, and use four credible sources to support your claims. Use [MLA, APA, Ancient Sumerian] method of citation, and [this font that I happen to like], have a summary or funnel introduction, put your thesis at the end of your introduction, and use correct English.

Having directed a Writing Center for six years, I can say that this is the fallback writing assignment for people all over the university. Sometimes the last three criteria aren’t mentioned, but are simply assumed as included in the “well-organized” criterion.

You get this paper from your student Josef. The introduction is:

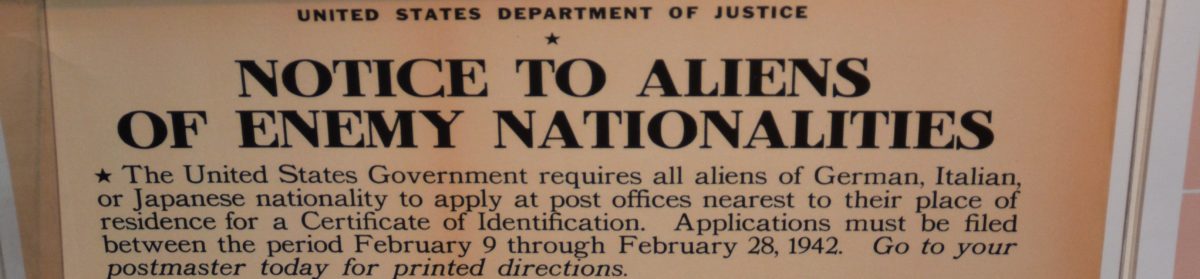

Since the dawn of time there has been a problem with Jews. Now, more than ever, Germans are faced with the question of what to do with Jews. Making Germany great again requires expelling Jews because Jewish leftists agreed to the Versailles Treaty, leftist revolts made the major political figures believe they had to surrender, and Marx was a Jew.

The paper has three body paragraphs showing that each of those minor premises (his data) are true. They are, so he has no problem citing credible sources to support those claims. There are no grammar errors, and his citation is faultless.

What grade does this paper get?

On a rubric model, assuming the prompt implies the rubric, he could easily get a good grade. He cares about this issue, he has four credible sources, he uses the correct method of citation, the right font, his thesis is right there, he could easily have the kind of “organization” that student writing is supposed to have (which is specific to student writing, but that’s a different post), and he meets whatever idiosyncratic grammar rules the teacher has.

Josef might have worked a long time on this paper—should he get a good grade on the labor contract model?

If a teacher abides by the criteria implied by that assignment, they seem to be faced with giving him a bad grade because of his argument being awful (and it is)—which is a criterion not mentioned in the prompt–, or giving him a good grade because he met the criteria.

If we give him a bad grade because his argument is awful, we’ve introduced a new criterion, and one that only applies to him. Since Josef’s (false) narrative about him and his group is that they are persecuted by “leftists,” we seem to have given him evidence to support that claim of persecution. He would definitely get invited to go on Tucker Carlson’s show.

If we give him a good grade, we’re saying this is a good argument, and it isn’t.

So, what do we do with Josef’s paper?

This will take me several posts, but the short answer is: the problem is the prompt. It doesn’t ask that students engage in argumentation. We don’t do anything about Josef’s paper because we don’t give that prompt.

It’s fine if we choose to have an fyc program that doesn’t have the goal of teaching argumentation. FYC is overloaded with things it’s supposed to do, and it’s great if programs choose to do one or two things well rather than a lot of things badly. And those one or two things aren’t necessarily argumentation. What’s not fine is claiming that we’re teaching argumentation when we aren’t.

It’s also not fine to set teachers up for the false dilemma of how to deal with Josef’s argument, but that’s what we’re doing. There are many ways that we can write prompts that don’t put us (or teachers of fyc) in that false dilemma, and even many ways that do so while actually teaching argumentation.

“If we give him a good grade, we’re saying this is a good argument, and it isn’t.”

Well, no. That’s not necessarily what we’re saying. You mention labor contract grading, a model that (to varying degrees depending on how the contract is designed) explicitly divorces the grade from the quality of the submitted product.

You could argue that we OUGHT to ensure that our students’ grades reflect the actual quality of their finished assignments, but that’s precisely what labor-based grading proponents dispute. And if a labor-based grading contract is written at all well, then it should be clear what a grade does and does not indicate about a student’s performance.

You could also argue that Josef might be able to point to his transcript to make a deliberately misleading argument that he was a good writer based on his grade in my class, but if I have been clear about what my rubric (and therefore his grade) does and does not reflect, then that deception is not within my responsibility (I can’t single-handedly change the reductive way universities and others use grades), and if I’ve done my job at all well, such an argument at least won’t fool his classmates.

Labor grading contracts aren’t new, and, unfortunately, in my experience, students draw the conclusion that they’re good at this kind of labor. I think you’re describing practices that make it clear that you are not making qualitative assessments. But, you’re also saying that he could get a good grade.

So, teachers either need to be comfortable with giving appallingly unethical arguments a good grade, or they’re going to introduce a new criterion. In other words, and I probably said this badly, labor model grading doesn’t get you out of the false dilemma presented by that prompt.