Genesis Apologetics (GA) is a group that advocates what’s called “Young Earth Creation.” That is, they argue that the earth was created thousands of years ago, and that a correct reading of Scripture requires that we believe that: “The genealogies in Genesis clearly map to Adam who was created by God out of dust just thousands of years ago, and they are even affirmed by the New Testament writers.”

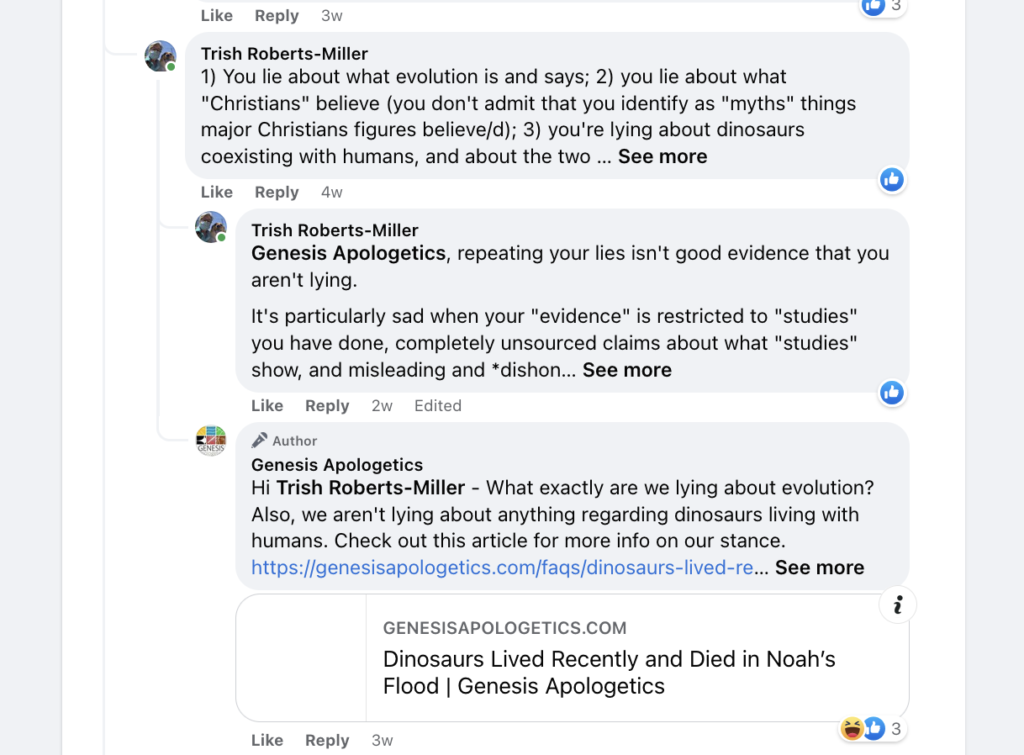

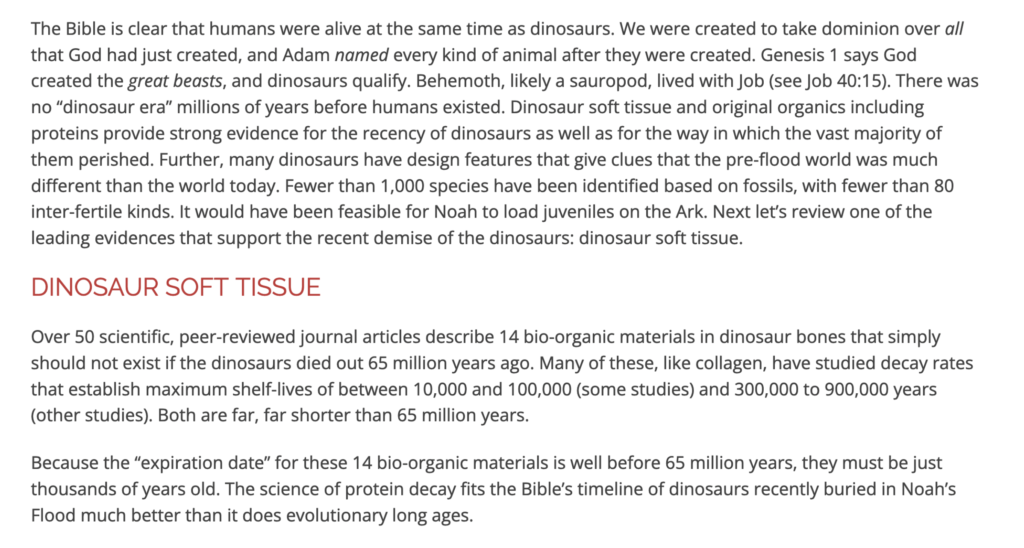

They posted something called the “Seven Myths” , and, as you can see above, I objected. (They’ve since deleted the whole thread for that posting, but they’ve reposted the link.) They recommended another page, one which claims that “Over 50 scientific, peer-reviewed journal articles described 14 bio-organic materials in dinosaur bones that simply should not exist if the dinosaurs died out 65 million years ago.”

They don’t cite any articles that show bio-organic materials that shouldn’t exist. They cite, as far as can tell, about five scientific studies, most of which are authored by Mary Schweitzer. And she says they misrepresent her work.

“Young-earth creationists also see Schweitzer’s work as revolutionary, but in an entirely different way. They first seized upon Schweitzer’s work after she wrote an article for the popular science magazine Earth in 1997 about possible red blood cells in her dinosaur specimens. Creation magazine claimed that Schweitzer’s research was “powerful testimony against the whole idea of dinosaurs living millions of years ago. It speaks volumes for the Bible’s account of a recent creation.”

This drives Schweitzer crazy. Geologists have established that the Hell Creek Formation, where B. rex was found, is 68 million years old, and so are the bones buried in it. She’s horrified that some Christians accuse her of hiding the true meaning of her data. “They treat you really bad,” she says. “They twist your words and they manipulate your data.””

In other words, her work does not support their claim. They’re being dishonest by suggesting it does.

Just to be clear: however you read Scripture is between you and God. You can, as does GA, jump among translations to get the reading that supports what you want to believe about Scripture, ignore all the passages that say you’re wrong (Paul said Scripture should be read allegorically), ignore all the many major figures in Christianity who didn’t and don’t read Scripture as does GA. You be you. But, if you want to impose this marginal reading of Scripture on students in schools by claiming it’s science, then suddenly the lies about the research (and Scripture) matter.

When I say this to individuals, they say, “They can’t be lying because they’re good people.” What that means is that they can’t be lying because I trust them. That’s how lying works. The most appalling, and un-Christian, lie is implicit—that their (incredibly cherry-picked and inconsistent) claims are things about which Scripture is “clear” (below I’ll mention the “great beasts” problem) . So, people feel that either they must believe what GA says, or they must reject Scripture as an authority.

Paul didn’t read Scripture literally; why should you?

I am really troubled by how many people I meet who were told, over and over, and so they believe that being Christian means believing, as GA says, that being a Christian requires that they believe their marginal, rigid, internally contradictory, ideologically driven cherry picking, and hermeneutically indefensible reading of Scripture. So, when they realize that much of what they have been told ranges from misleading to false, they think they can’t be Christian.

Honestly, I think that groups like GA create more atheists than Richard Dawkins ever could in his wildest dreams.

They create a falsely stark world of people who believe that Scripture is God’s Truth and Darwinists. There are three problems with that false binary. First, most people who believe that Scripture is God’s Truth don’t believe the claims that GA makes. Second, if what you’re saying is God’s Truth, you don’t have to be deceptive about what’s in Scripture (e.g., dinosaurs and “great beasts”—I’ll get to that). Third, Darwin didn’t invent evolution, but he proposed an explanation that made sense of what people were already observing. Evolutionary biology has evolved far beyond Darwin. Calling evolutionary biology Darwinism would be like calling Christianity “Origenism.”

As Christians, we would resent being characterized by what Origen said. He didn’t invent Christianity, and not all Christians believe everything he said. Origin of Species is not the Bible of evolutionary thinking. Scientists don’t have originary documents to which they refer deferentially.

I’m talking about Origen in order to make two points: there is not a world in which you are either a Christian or a Darwinist; when Christians characterize all believers in evolution as Darwinists we are doing something we would not want done unto us—that is, attributing to them beliefs they don’t have.

Here’s the bigger problem. GA claims that their claims are scientific, and supported by scientific studies. And, as indicated in the Schweitzer quote above, their position is not scientific and not supported by the five studies they cite, let alone the fifty the claim. I’ll just talk about the first three paragraphs of one page because otherwise this post would be way too long (these paragraphs are pretty indicative of how the whole post runs):

I’m not going to spend much time on their problematic Scriptural exegesis, but it’s worth considering. They claim that the Bible is “clear” except they jump around translations to get the reading they need. So “the Bible” isn’t “clear.”

I’ve asked, repeatedly, about their claim that Genesis 1’s mention of “great beasts” is proof of the existence of dinosaurs. As far as I can tell, the few translations that use that term are clear that those creatures are sea creatures.

But, unlike Genesis Apologetics, I’m open to correction on this. If they don’t correct me, then, as I suspect, they’re lying about Scripture. But, let’s go back to the third paragraph quoted above.

The most important claim has three parts: first, that there are bio-organic materials in dinosaur, and second, that these bio-organic materials should not exist, and that there are studies to support these two claims.

For the Genesis Apologetics argument to be true, all three claims have to be responsibly supported—that there are these materials, and that they shouldn’t exist, and that there are fifty peer-reviewed citations that support both of the previous claims. Just to drive home the point of how irresponsible their argument is, their claim is supported by “science” because “some studies” and “other studies” support [something? maybe the argument they’re making? maybe some part of it?]. That isn’t exactly support. That’s how some jerk next to you on an airplane argues. That’s a flunk first-year composition level of citation.

And they cite no studies that say what Schweitzer has found are proof that the standard narrative about evolution is wrong.

If you want to read Scripture in a way that can only be achieved by jumping around among translations, being dodgy about references, and deciding to ignore theologians whose Greek and Hebrew is probably better than yours, you be you.

Here’s the problem. If you take your personal and minority interpretation–even among Christians–reading, and try to make it the basis for public policy (what is taught in schools, what laws we as a public have), then, as someone claiming to be Christian, you should meet two standards. First, you should do unto others as you would do unto them. That is, you should enter the realm of policy argumentation, holding your opponents to the same standards of proof, rationality, civility, and so on as you hold yourself.

If you do that, which GA doesn’t, then this whole reading collapses. GA does not hold itself to the same standards of proof as it holds advocates of evolution. It does not treat them as it wants to be treated.

If you decide that it’s okay to hold your beliefs to different standards of proof than you hold believers in evolution (as GA does), then, someday, you’re going to have to look Jesus straight in the face and tell him that you decided what he very clearly told us to do didn’t apply to you. Good luck with that.

Second, let your yea be yea and your nay be nay. Christians should not be Machiavellians, deciding that dishonesty is okay if we do it because we have a higher truth, or we have a good cause.

Jesus doesn’t need liars on his side.