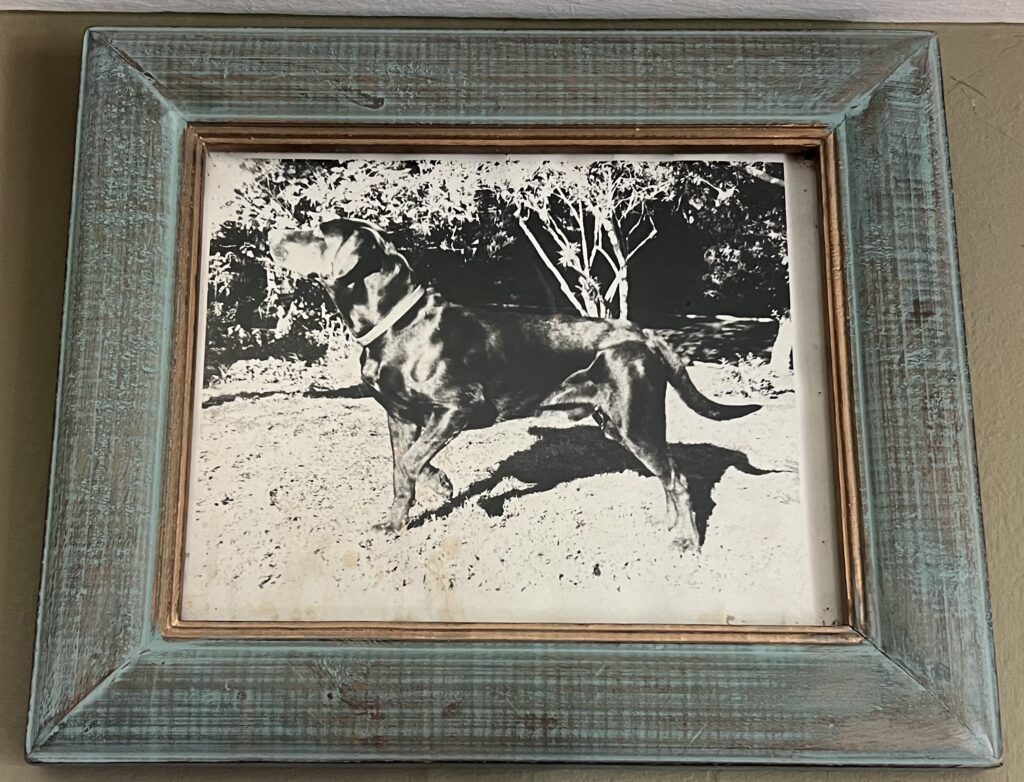

When I was a kid, my family got a dog, and I got sent to doggy training school with this dog. This was in the day when you didn’t start training your dog till it was six month old, since the training consisted of yanking it around with a choke collar. (I’ve since been told that this method was actually popularized by literal Nazis. I choose to believe that’s true.) Since the dog weighed as much as I did, it didn’t go well. Or maybe it did. During the whole training, he was the least well-behaved dog in the class (with some kind of shepherd a close second). On the day of the final exam, it was windy and there were bits of paper, bags, and leaves blowing around. Almost every other dog in the class was out of their minds running after the flotsam. Jack got first place, since he was the least badly-behaved dog in the class. (The Shepherd got second.) Jack went on to be a wonderfully well-behaved dog, within reason. (Where he found all those bras he placed on the front lawn I don’t know.)

When I was an adult, I got a Malamute mix, and went to a dog training class. The trainer, who had a Sheltie, gave us lots of advice, and had us do things like teach a long recall by having the dog attached by a long length of clothesline. The scar between my fingers is no longer visible. For complicated reasons, I also ended up with a Dane/Shepherd mix (Chester Burnette). So I trained both dogs. Chester was so good he became a demo dog, and I flirted with the idea of becoming a dog trainer. After all, I had done such a great dog with Chester. This is called post hoc ergo propter hoc. Meanwhile, the Malamute mix (named Hoover) would take off if the door was opened more than two inches. I dismissed that training failure as my not having been experienced enough. Nah. He was a Malamute.

I read a lot of books and articles on dog training (and a fair amount on cat training), and it was all very emphatic, very clear, and contradictory. It was all in the genre of “You just have to [do this one thing] and you will have a perfectly behaved dog.” But, were that true, then there would only be one dog training book, or all the books would say the same thing. There’s more than one book, and they contradict each other. So, training a dog is not a simple thing that involves doing just this one thing.

I ended up deciding that all the advice was good. It had worked for the trainer, and their training of their dog. Almost all advice about dog training is good, but it isn’t all relevant to every situation. At that time, there was a big thing about dominance in dog training (the Monks of New Skete were big), and that worked with the Malamute. If I wanted him to sit, I needed to plant my feet, stand up straight, and say, “Sit” like I was a boot camp instructor. That was good advice. For Hoover.

If I did that with Chester, he would climb onto the couch and cover his eyes with his paws. It was bad advice for Chester.

At 38, I became a parent. I didn’t want to parent the way my parents had, so I read so very many books on parenting. And it was just like the dog training books. Every book said that you should do it this way because it worked for us. And, like the dog training books, they contradicted each other. I’m willing to believe it did work out for them. But, were raising a child easy and straightforward, there would be one parenting book, or they would all say the same thing, There isn’t and they don’t.

Almost all advice about parenting is good, insofar as I’m certain it works for some parents with some children, but it isn’t all relevant to every situation. One of the particularly rigid and doctrinaire books was written by someone who had to retract a lot of it when they had a special needs child.

In other words, I think a lot of both dog training and parenting advice is post hoc ergo proctor hoc. People engaged in certain practices (or believed they did), and they got a good outcome, so they believe that those practices led to those outcomes. And they told others to do it the way they believed they had done it. Maybe. Maybe not. Maybe the dominance-based practices of the Monks of New Skete worked despite what they did; maybe the “spare the rod” folks did more damage than good, but had enough kids enough not-damaged that they could claim success.

More important, even if those practices worked for them, that doesn’t mean that those practices will work for everyone.

I started working in a Writing Center when I was around 19. And I’ve been paying attention to advice about writing ever since. It’s almost all good, even Strunk and White, in that it’s almost all going to work for someone in some situation. Some writers get through a whole career by working themselves into a shame-filled panic. I have never met a successful writer who wrote a Ramistic outline before starting a draft, but I suspect Cotton Mather did, and he wrote a lot. I met a writer who claimed to write from beginning to end without substantial revising. I’m dubious, but maybe it worked for him. Some people write for two hours every morning; some people write late at night; some people find that binge-writing works for them; some people write a little every day.

So, I wish that people looking for advice on any of those things knew that just because someone thinks something worked for them doesn’t mean it actually did, although it might have, but that doesn’t mean you’re at fault if it doesn’t work for you.

Self-help rhetoric is pretty consistent. It has these steps:

1) You are failing at what you want to do;

2) You can succeed if you do this simple thing;

3) I know because this simple thing has worked for me, and the people with whom I’ve worked.

There are lots of great things about self-help rhetoric. It’s comforting. It’s hopeful. But the way in which it’s hopeful (“all you have to do is [this]”) can mean it’s shaming when it doesn’t work. And that’s the moment when the simplicity of self-help rhetoric becomes toxic.

Self-help advice is always true in that it has worked for someone. But it’s never always true. And it never makes writing, or training a dog, or raising a child, easy. Because none of them is an easy thing to do.

Unless you have a sheltie.

My best writing teachers in an MFA program in New York knew many things about writing (and life, too) and treated every piece of writing to undergo the workshop treatment as unique (as each writer deserves).

Needless to say you can’t fit brilliance in a formula, and I learned from them (I can name names) but not how to be brilliant