Despite the fact that invoking Hitler in arguments is so kneejerk that there’s even a meme about it, a surprising number of people misunderstand the situation. They misunderstand, for instance, that he was elected; he was even voted into dictatorship. So, why was he elected?

I want to focus on four factors that are commonly noted in scholarship but often absent from or misrepresented in popular invocations of Hitler: widespread resentment effectively mobilized by pro-Nazi rhetoric, an enclave-based media environment, authoritarian populism, agency by proxy/charismatic leadership.

I. Resentment

Resentment is often defined as a sense of grievance against a person, but grievances can be of various kinds, including motivating positive personal change or political action. Resentment is grievance drunk on jealousy. It’s common to distinguish jealousy from envy on the grounds that, while both involve being unhappy that someone has something we don’t, jealousy means wanting it taken from the other. If I envy someone’s nice shirt, I can solve that problem by buying one for myself; jealousy can only be satisfied if they lose that shirt, they are harmed for having the shirt, or the shirt is damaged. My jealousy can even be satisfied without my getting a shirt—as long as they lose theirs. Jealousy is zero-sum, but envy is not.

Resentment is a zero-sum hostility toward others whom I think look down on me. Although I feel victimized that they have something I don’t, I don’t necessarily want what they have. I do, however, want them to lose it; I want them crushed and humiliated for even having it. Resentment relies on a sense that others have things to which I am entitled, and they are not. In addition, resentment always has a little bit of unacknowledged shame.

Many Germans (most? all?) resented the Versailles Treaty, and they resented losing the Great War. They resented the accusation that they were responsible for the war, they resented that they lost a war they believed they were entitled to win, and they resented a treaty as punitive as the kind they were accustomed to impose on others.

Certainly, the Versailles Treaty was excessively punitive, but it was, oddly enough, fair—at least in the sense that it was an eye for an eye. Germans didn’t condemn equally punitive treaties they had imposed on others (e.g., the Treaty of Frankfurt or the 1918 Brest-Litvosk Treaty. They resented being treated as they felt entitled to treat others.

The war guilt clause was a particular point of resentment, and yet it was partially true. The notion that one nation and one nation only can cause a world war is implausible—few wars are monocausal—but certainly Germany held a large part of the responsibility. Yet Germans liked to see themselves as forced into a war they didn’t want—they were the real victims and completely blameless. Were the Germans actually truly blameless, I don’t think the Treaty of Versailles would have been as useful a tool for mobilizing resentment.

Sloppy pan-Germanism mixed with the even sloppier Social Darwinism promoted a narrative that victory always goes to the strongest, and that therefore whoever win deserved it. The German defeat in the Great War therefore was a massive blow to German ideology—if the best always win, and the winners are always the best, that loss was stuck in the craw. People who enjoyed Nazi rhetoric resented that they lost a war they felt entitled to win.

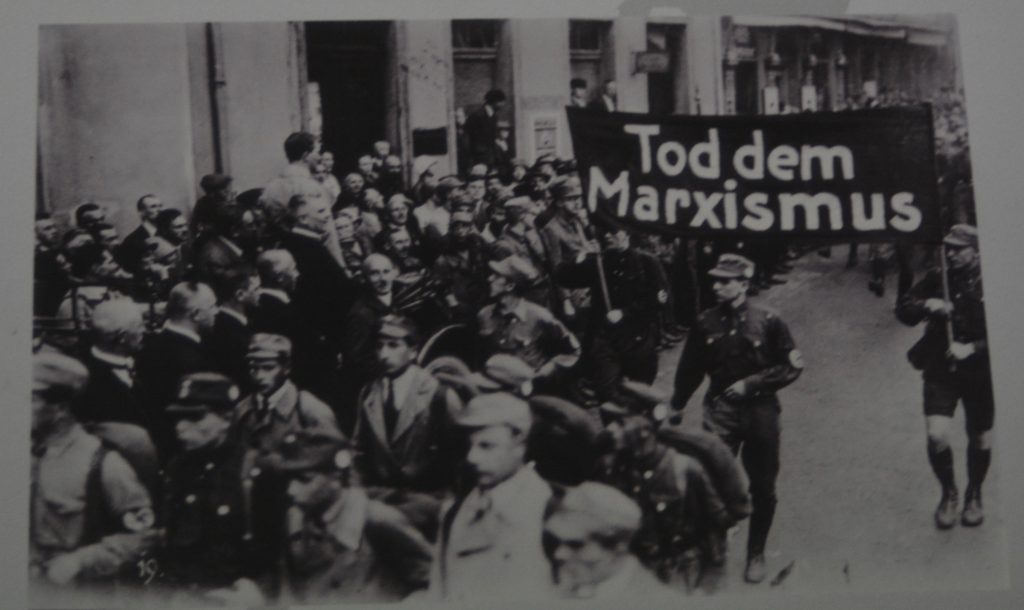

Important to Nazi mobilization of that resentment was continually reminding audiences of it—there are few (any?) Hitler speeches in which he didn’t remind his audience of the humiliation of the Versailles Treaty, and of the way that other nations looked down on and victimized Germany.

Did everyone else really look down on Germany? The French probably did, but that’s just because they looked down on everyone. Some British and Americans did; some didn’t. But the Germans certainly looked down on everyone. So, like the resentment about punitive treaties, they weren’t on principle opposed to people looking down on others; they just resented when they thought they were being looked down on.

The Versailles Treaty didn’t actually end the fighting. Pogroms, forced emigration, violent clashes, and genocides raged through Eastern and Central Europe well after the war, causing a massive immigration crisis. And, as often happens, people resented the immigrants. They also resented liberals, intellectuals, Jews, and various other groups that they imagined looked down on them.

Resentment is an act of projection and imagination.

II. Enclave-based media environment

Weimar Germany had a lot of political parties (around forty, depending on how you count them), which can loosely be categorized as: Catholic, communist, conservative, fascist, liberal (in the European sense), and socialist. They all had their own media (mostly newspapers), and many of them were rabidly partisan in terms of coverage but without admitting to the partisan coverage. [The antebellum era in the US was much the same.]

The important consequence of this factionalized media landscape was that it was possible for a person to remain fully within an informational enclave: foundational narratives, myths, premises, and outright lies were continually repeated. Repetition is persuasive. Since factional media wouldn’t present criticism or even critics fairly (or at all), it was possible for someone to feel certain about various events and yet be completely wrong. Germany was not about to win the war when it capitulated.

Sometimes the narratives were specific (e.g.,The Protocols of the Elders of Zion documents the plot of international Jewry ), and sometimes about broader historical events, or history itself. One of the most important narratives was the shape-shifting “stab in the back” myth about the Great War. This myth said that Germany was just about to win the war, and would have, but the nation was stabbed in the back, and therefore had to accept a humiliating treaty. As Richard Evans has shown, just who stabbed the back, or when, or why, or even what back, varied considerably. Like a lot of myths, it was simultaneously detailed and inconsistent.

Another important narrative was a similarly specific and vague narrative about the course of history, as a survival of the fittest conflict undermined by liberal democracy. This narrative typically cast Jews as intractably incapable of patriotism, assimilation, or German identity. German exceptionalism denied the actual heterogeneity of

Of those six kinds of political parties, three were explicitly and actively hostile to democracy, either advocating a return to the monarchy (Catholic) or a new system entirely (fascist, communist). Some “conservatives” parties advocated a return to monarchy, some advocated some other kind of authoritarian government, and some at least seemed willing to accommodate democratic decision-making practices. Only the liberals and socialists actively supported democracy (communists wanted a Marxist-Leninist revolution and dictatorship of the proletariat, whereas socialists agreed with Marxist critiques of unconstrained capitalism, but wanted reform via democratic processes; “liberals” believed in a free market and democratic processes of decision-making).

What’s important about this kind of media environment is that it undermines democratic practices because it enables the demonization or dismissal of anyone who significantly disagrees. Repetition is persuasive. If you are repeatedly told that socialists want to kick bunnies, and never hear from socialists what they actually advocate, then you’ll believe that socialists want to kick bunnies. That makes them people who shouldn’t be included in the decision-making process at all; it personalizes policy disagreements. Policy disagreements, rather than being opportunities for arguing about the ads/disads, costs, feasibility, and so on of our various policy options (even vehemently arguing) is a contest of groups.

Tl;dr If you only get your information from in-group sources, then chances are that you never hear the most reasonable arguments for out-group policies; therefore everyone who is not in-group will seem unreasonable. Not hearing the arguments leads to refusing to listen to the people.

Repetition coupled with isolation from reasonable counterarguments radicalizes.

III. Authoritarian populism

One way to misunderstand how persuasion works is to imagine out-groups and their leaders as completely and obviously evil—by refusing to understand what some people find/found attractive about such leaders, we make ourselves feel more secure (“I would never have supported Hitler”), and thereby ignore that we might get talked into supporting someone like that.

Nazism is a kind of “authoritarian populism.” Populism is a political ideology that posits that politics is a conflict between two kinds of people: a real people whose concerns and beliefs are legitimate, moral, and true; a corrupt, out-of-touch, illegitimate elite who are parasitic on the real people. Populism is always anti-pluralist: there is only one real people, and they are in perfect agreement about everything. (Muller says populism is “a moralized form of antipluralism” 20).

Populism become authoritarian when the narrative that the real people have become so oppressed by the “elite” that they are in danger of extermination. At that point, there are no constraints on the behavior of populists or their leaders. This rejection of what are called “liberal norms” (not in the American sense of “liberal” but the political theory one) such as fairness, change from within, deliberation, transparent and consistent legal processes is the moment that a populist movement becomes authoritarian (and Machiavellian).

As Muller says, “Populists claim that they, and they alone, represent the people” (Muller 3). Therefore, any election that populists lose is not legitimate, any election they win is, regardless of what strategies they’ve used to win. Violence on the part of the in-group is admirable and always justified, purely on the grounds that it is in-group violence. The in-group is held to lower moral standards while claiming the moral highground.

Authoritarian populism always has an intriguing mix of victimhood, heroism, strength, and whining. Somehow whining about how oppressed “we are” and what meany-meany-bo-beanies They are is seen as strength. And that is what much of Hitler’s rhetoric was—so very, very much whining.

And that is something else that authoritarian populism promises: a promise of never being held morally accountable, as long as you are a loyal (even fanatical) member of the in-group (the real people).

In authoritarian populism, the morality comes from group membership, and the values the group claims to have—values which might have literally nothing to do with whatever policies they enact or ways they behave.

IV. Charismatic leadership/agency by proxy

Authoritarian populism needs an authority to embody the real people. It’s fine if they’re actually elite (many people were impressed by Hitler’s wealth). Kenneth Burke talked about the relationship in terms of “identification”—they saw him as their kind of guy. They imagined a seamless connection with him. In charismatic leadership relationships, the followers attribute all sorts of characteristics to their leader (which the leader may or may not actually have): extraordinary health, almost superhuman endurance, universal genius, a Midas touch, infallible and instantaneous judgment, and a perfect understanding of what “normal” people like and want.

In general, people engage in intention/motive-based explanations for good behavior on the part of the in-group and bad behavior on the part of non in-group leaders and members, and situational explanations for good behavior on the part of the non in-group and bad behavior for the in-group.

So, if Hubert (in-group) and Chester (out-group) give a cookie to a child (good behavior), then it shows that Hubert is good and generous (motive/intention), but Chester only did so because he was forced by circumstances (situational).

If Hubert (in-group) and Chester (out-group) both steal a cookie from a child (bad behavior), then it was because Hubert didn’t see the child, the child shouldn’t have been eating the cookie, he had no choice (situational explanations), but Chester stealing the cookie was deliberate and because Chester is evil.

One sign, then, of a charismatic leadership relationship is whether the follower holds a leader to the same standards of behavior as non in-group leaders, or if they flip the intention/situation explanations in order to hold on to the narrative that the in-group is essentially good.

What we get from a charismatic leadership relationship is a fairly simple way of understanding good and bad—it reduces moral complexity and uncertainty. Since our group is essentially good, we are guaranteed moral certainty simply by being a loyal member. And that is what Hitler promised.

Because Hitler is like us, and really gets us, then we are powerful—we take pride in everything he does; we have agency by proxy.

But, because we identify with him, then our attachment to him means we will not listen to criticism of him—criticism of him is an attack on our goodness. Our support becomes non-falsifiable, and therefore outside the realm of a reasonable disagreement about him, his actions, or his policies.

Charismatic leadership is authoritarian. But oh so very, very pleasurable.

Sources:

There are still lots of arguments among scholars about Hitler, the Germans, and the Nazis, but nothing I’m saying here is either particularly controversial or something I’ve come up with on my own.

While it is a mistake to attribute magical qualities to Hitler’s rhetoric, and to attribute the various genocides and disasters to him personally (as though his personal magnetism was destroyed agency on the part of Germans), it is also a mistake to think the rhetoric was powerless. Germans elected him because they liked what he had to say.

There was a time when scholars were insistent that Hitler’s rhetoric wasn’t that great (an argument that Ryan Skinnell’s forthcoming book will show was an accusation made at the time, one that completely misses the rhetorical force of Hitler’s strategies), but that was partially a reaction to the immediate post-war deflecting of German responsibility for the war, the Holocaust, the various genocides (the argument was that Germans were overwhelmed by Hitler’s rhetoric, or secretly hated him—neither was true).

There are many excellent biographies of Hitler, the ones written after the opening of the records captured by the Soviets are the most useful. Kershaw’s writings are especially readable, but Volker Ullrich’s and Peter Longerich’s biographies have been able to take advantage of more recent research (If I were asked to recommend just one biography, it would be Longerich’s). Richard Evans’ three-volume study of Nazism (coming to power, in power, at war) is thorough and makes clear the enthusiastic participation of various other leaders.

Adam Tooze’s Wages of Destruction is a compelling and detailed analysis of the economy under the Nazis, and Nicholas Stargardt’s The German War shows the considerable support Nazis had throughout the war. There are a lot of books about the media and Hitler, but I think the best place to start is Despina Stratigakos’ Hitler at Home. Robert Gerwarth’s The Vanquished is a powerful discussion of the aftermath of the Great War.