I’ve known a lot of people, both personally and virtually, who were Followers. Sometimes they changed churches multiple times, sometimes philosophies, political ideologies, identities (like the guy I knew in college who flailed around from preppie to Che-Marxist to tennis fanatic—each with an entirely new wardrobe), with each new identity/community the one to which they were fully committed.

I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with changing wardrobes, identities, churches, even religions. People should change. What made (and makes) these people different is how they talk(ed) about each new conversion—this group was perfect, this group made them feel complete, this group/ideology answered all their questions, gave meaning to their lives, was something to which they could commit with perfect certainty.

That they went through this process multiple times, and kept failing to find a community/ideology that continued to satisfy them never made them doubt the quest, nor doubt that this time they found it. And I thought that was interesting. Each of these people was just someone in my circle of acquaintance for a few years, and I eventually lost track of them—in three cases because they’d joined cults.

There were (are) a lot of interesting things about these people, not just that their continued disenchantment never made them reconsider their goals, but also that they didn’t see themselves as followers at all, let alone Followers. They saw themselves as independent people, critical thinkers, autonomous individuals of good judgment—who were continually searching for, and temporarily finding, a group or ideology that enabled them to surrender all judgment and doubt. That’s a paradox.

In the mid-thirties, Theodore Abel, an American sociologist, offered a prize of 400 German marks for “the best” personal narrative of someone who had joined the Nazis prior to 1933—essentially a conversion narrative. In 1938, he published a book about it. The Nazis sounded like my various acquaintances, not in terms of being Nazis, but as far as simultaneously seeing (and representing) themselves as autonomous individuals of purely independent judgment who were seeking a totalizing group experience—one that demanded pure loyalty and complete submission.

They were Followers.

In the Platonic dialogue Gorgias, Socrates gets into an argument with two people who want to study rhetoric so that they can control the masses and thereby become powerful, perhaps even a tyrant. When Socrates asks why, one of them answers, more or less, “For the power. D’uh.” And Socrates says, “Does the tyrant really have the power?” Socrates points out that the tyrant is, in a way, being controlled by the masses he’s trying to control. He can’t, for instance, advocate what he really thinks is best, but only what he thinks his base will go along with.

It’s a typically paradoxical Socratic argument, but there’s something to it. The tyrant can only succeed as long as he (or she—not an option Socrates and the others considered) gives the Followers what they want. In other words, if we care about tyrants, we should see the source of power as Followers. Instead of asking why tyrants (or demagogues) do, we should ask what Followers want. So, what do Followers want?

Here’s the short version. They want a leader who speaks and acts decisively for them, who is a “universal genius,” and whose continued success at crushing and shaming opponents not only gives them “agency by proxy” in that shaming and crushing, but confirms the followers’ excellent judgment in having chosen to follow, and who is supported by total loyalty.

That’s the short version. Here’s the longer.

They want a leader who is a “universal genius,” not in the sense of a polymath (someone trained or educated in multiple fields), but in the sense of a person who has a capacity for seeing the right answer in any situation, without training, or expertise, or prior knowledge. This genius can lecture actual experts on those experts’ fields, correct their errors, see solutions they’ve overlooked simply because of his extraordinarily brilliant ability to see.

Followers’ model of leaderhips assumes that there is a right answer, and that’s something else that the followers want—the erasure of a particular kind of uncertainty. They don’t mind the uncertainty of a gamble, as long as the leader expresses confidence in his ability to succeed at what is obviously to him the right course of action. They mind the uncertainty of a situation that might not have a single right answer, or in which an answer isn’t obvious to them, or, even more triggering, in which the right answer isn’t obvious to anyone. That anger and anxiety are heightened if they are responsible for making the choice, since now they face the prospect of being shamed if they turn out to be wrong.

Avoiding shame is important to Followers, and they often associate masculinity with decisiveness. Not just the decisiveness of making a decision quickly (they don’t always require quick decisions), but of deciding to take action, to do something, powerful, dramatic, clear. Followers like things to be black and white, and they want a leader whose actions are similarly stark, and who advocates those actions in similarly stark terms. Followers don’t like nuance, hedging, or subtlety, but that doesn’t mean they reject all kinds of complexity.

They don’t mind complexity of a particular kind. Followers can enjoy if the leader explains things in ways that don’t quite make sense, or endorse an incoherently complicated conspiracy theory—the leader’s ability to understand things they can’t confirms their faith that he is a genius. That the leader is confidently saying something that doesn’t quite sense is taken by Followers to mean that, while things might seem complicated to the follower, they are clear to the leader. Thus, the leader has a direct connection to the ways of the universe–universal genius. Not quite making sense confirms that perception of the leader as a person who clearly sees what is unclear to others, but hedging or nuance would suggest that the leader does not perceive things perfectly clearly, and that is unacceptable in the leader.

Followers’ sense of themselves as people with excellent judgment—autonomous thinkers who are completely submitting their judgment to the leader–requires that the leader always be confident, clear, and describe issues in black and white terms.

This part is hard to explain. These Followers I knew kept looking for a system of belief that would mean they were not only never wrong, but never unsure, never in danger of being wrong, of being shamed. And, like many people, they equated clarity with certainty and certainty with being right, and they equated nuance and hedging with uncertainty, and uncertainty with being more likely to be wrong. Thus, a leader who says, “This is absolutely true–even if it isn’t– is more trustworthy than one who hedges because the first leader has more confidence. Being confident is more important than being accurate. (“It’s a higher truth,” Followers tell me.)

It’s interesting that, sometimes, a leader can take a while to make a decision, but, when he does make it, he has to announce his decision in unequivocal terms and enact it immediately, since that signals clarity of purpose and confidence. To put his decision into the world of deliberation and disagreement would be to allow the decision of a genius to be muddled, compromised, and dithered. Followers mistake quick action justified by over-confidence for a masculine and decisive response. They mistake recklessness for decisiveness–because they admire recklessness, since it signals faith, will, and commitment.

Followers need the leader to give them plausible narratives that guarantee success through strength, will, and commitment. So, what happens when the leader fails? At that point, we get scapegoating and projection. Oddly enough, Followers can tolerate complicated conspiracy narratives, even ones they can’t entirely follow, as long as the overall gist of the narrative is simple: we are good people entitled to everything we want, and They are the ones keeping us from getting it. We are blameless.

Followers don’t care if the leader lies. They like it. They don’t feel personally lied to, and they like that the leader can get away with lying—they admire that degree of confidence, and the shamelessness. They want a shameless leader. They want a leader who isn’t accountable; they want one without restraints. They don’t see the leader engaging in quid pro quo, violating the law, or even openly lining his pocket as a problem, let alone corruption. They think that’s what power is for. And, as with the lying, they admire the shamelessness.

They also like if the leader says ridiculously impossible things; they like the hyperbole. They think it signals passionate commitment to their cause because it is unrestrained.

They don’t expect the leader to be loyal to individuals, although the leader demands perfect loyalty from individuals, and Followers demand perfect loyalty from the leader’s subordinates. If leader’s aides betray the leader in any way, such as revealing that the leader is incompetent, Followers are outraged, even if everything the aide says is true.

This part is also hard to explain, so I’ll try to explain. A Follower I knew was on the edges of a cult run by a man who called himself various things, including Da Free John. At one point, Da Free John had followers who came forward and accused him of, among other things, egregious sexual harassment. Those accusations inspired my friend to get more involved with the cult. When I asked about the accusations, he was angry with the people who had made the accusations. His argument was something along the lines of, “They knew what they were getting into, and they betrayed him.” In other words, as far as I could tell, he was willing to grant the sexual harassment, but blamed the victims, not just for being victims, but for being disloyal enough to complain about it.

Albert Speer was condemned for his disloyalty, as though he should not have admitted to any flaws in Hitler (I think condemning him for his being a lying liar who lied is reasonable criticism, but not disloyalty). Victims of abuse by church officials are regularly condemned for their disloyalty, as though that’s the biggest problem.

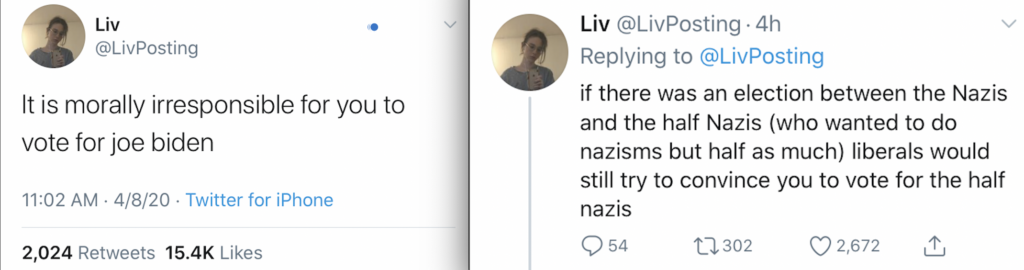

Followers pride themselves on their ability to be loyal, and they will remain loyal as long as the leader continues to be a beacon of confidence, certainty, decisiveness. That commitment can even withstand some serious failures on the part of the leader, for a few reasons. The most important, mentioned above, is they refuse to listen to any criticism of the leader, even if made by informed people (such as close aides). Followers only pay attention to pro-leader media, and they dismiss as “biased” any media (or figure) critical of their leader. This dismissing of criticism of the leader as “biased” is not only motivism, but ensures that Followers remain in informational enclaves, ones that will spiral into in-group amplification (aka, “rhetorical radicalization“).

If the leader does completely fail, they are likely to blame his aides, rather than him (as happened with a large number of Germans in regard to Hitler). To admit the leader was fallible would be to admit that the Follower had bad judgment, and that’s not acceptable.

So, what I’m saying is that Followers are people who put perfect faith in a leader, a faith that is impervious to disproof, and they refuse to look at any evidence that their loyalty might be displaced. The conventional way to describe that kind of relationship is blind loyalty, but they don’t think they have blind loyalty (they think the out-group does). They think their loyalty is rational and clear-eyed because they believe they have the true perception of the leader, one that comes from an accurate assessment of his traits and accomplishments. They believe the leader is transparent to them.

But, if this isn’t blind loyalty, since they refuse to look at anything outside of their pro-leader media, it’s certainly blindered loyalty. And it generally ends badly.