Here is a Nazi poster–the loose translation is, “This patient with a hereditary disease costs the people 60000 Reichsmarks for life. That is your money.”

Retired Professor, Writing Center Director, Scholar of train wrecks in public deliberation

Here is a Nazi poster–the loose translation is, “This patient with a hereditary disease costs the people 60000 Reichsmarks for life. That is your money.”

Like many teachers trying to shift to online teaching and still provide a useful experience for students, I’m got way too much to do this week, and so I don’t have the time I’d like for writing about Trump’s putting a “strong” economy over the health of the people he is supposed to care for. I don’t even have the time to point out that his first moves were not to protect the economy, but the stock market. (They are not the same thing.)

All I have time for is to make a few quick points that others have already said. There are lots of ways that Trump could help the economy that would, in fact, raise all boats (something that boosting the stock market does not do)—FDR figured them out. This isn’t about fixing the economy; this is about fixing the perception of the economy (since so many people do associate “the economy” with “the stock market”).

I’m about to give an example of how that way of thinking of things worked out for another world leader in order to make the point that it isn’t a good way to approach the situation. I want to give an example in order to make a claim about process—whether this way or approaching a situation is a good one.

My rhetorical problem is that a lot of people (especially authoritarians) have trouble making that shift to the more abstract question of process. It has nothing to do with how educated someone is—I’ve known lots of people with many advanced degrees who couldn’t grasp the point, and many people with no degrees who could. It’s about authoritarian thinking, not education. (Expert Political Opinion and Superforecasting are two books about this phenomenon.)

To complicate things further, authoritarians (who exist all over the political spectrum) not only have trouble thinking about process, but understand an example as a comparison, and a comparison as an analogy, and an analogy as an equation.

For instance, imagine that you and I are arguing about whether Chester’s proposal that we pass a law requiring that everyone tap dance down the main street of town is a good one, and you point out that the notoriously disastrous leader of the squirrels, Squirrely McSquirrelface, passed a similar law, and it ended disastrously. If I’m an authoritarian, then I’ll sincerely believe that you just said that Chester is Squirrely McSquirrelface, and, in a sheer snitfit of moral outrage, I will point out all the ways he isn’t. For extra points, I will accuse you of being illogical.

All that I will have thereby shown is that I don’t understand how examples about processes work.

I’ll give one more example. I often get into disagreements with people about “protest voting” (or “protest nonvoting”). I think that’s a bad way to think about voting, since I don’t know of any example of a time it’s worked to get the kinds of political changes the people who advocate it want. And, instead of providing me with examples, the people with whom I’m disagreeing dismiss me for not having sufficient faith (a Follower move). They only argue about process deductively (from a presumption that purity of intent is not only necessary but sufficient for a good outcome—a premise I think is indefensible historically).

So, let’s get back to the question of privileging the stock market and “the economy” over what experts on health say. And there’s an example of that way of thinking. (There are a lot, but I’ll pick one.)

I think Trump, who didn’t want to be President, now can’t stand the idea of not being re-elected, because he is ego first and foremost (as indicated by all his lies, even on stupid stuff, like his height). And he believes that he can’t get reelected if the economy sucks in October. And that’s a reasonable assumption. People will vote against a President (Carter) or party (GOP in 2008) if the economy sucks at that moment, regardless of whether it sucks because the President did the right thing (Carter), or the economy tanked because of processes in which both Dems and GOP were complicit (2008). Hell, people vote on the basis of shark attacks.

There are many problems with Trump, but one is that he sincerely believes he is a “universal genius”—a person so smart he can see the right course of action, regardless of having no training in it. This is important to his sense of self, and that’s why he keeps firing people who make it clear that they are more knowledgeable than he is about anything. Not only can’t he be wrong, but he can’t have anyone in his administration smarter than he is.

This isn’t the first administration like that. It doesn’t end well. It can’t end well. The notion of “universal genius” is nonsense. Intelligent (as opposed to raging narcissist) people know that they don’t know everything, and so need people around them who know more than they do about all sorts of thing.

Intelligent people know that disagreement is useful. Raging narcissists fire people for disloyalty if they dissent, and then they make bad decisions. Firing people for “disloyalty” (i.e., dissent) doesn’t play out well in the business world (e.g., Enron, Theranos) in the long run (although it can in the short run), nor does it in the political world, nor the military.

Making decisions about the economy purely on the basis of how it will play out for a regime also doesn’t lead to good long-term outcomes. How Democracies Die shows how authoritarians shift from democracy to authoritarianism through disastrous manipulation of the economy.

There’s another example.

Germans, on the whole, never really admitted that they’d lost WWI. The dominant narrative was that they were winning, and could have won had people been willing to stick it out, but the willingness to stick it out collapsed for two reasons. First, there was the “stab in the back” myth—the notion that Jewish media lied to the Germans and said they couldn’t win. Second was the narrative that people on the homefront lost hope because they were suffering in basic ways, such as food, housing, and coal. And they were.

It’s important to note that the dominant narrative was wrong on both points. There wasn’t a stab in the back, and Germany didn’t lose the war because of homefront morale. The homefront morale could have stayed strong, and they would still have lost. It just would have taken longer and cost even more lives.

But Hitler believed that narrative, and both its points.

As Adam Tooze shows in his thorough book (that I can’t recommend highly enough), Hitler’s economic (and military) decisions were gambles. And those decisions were also at odds. He wanted to prevent the stab in the back by, as much as possible, ensuring that his base was comfortable. He made bad decisions about the economy because he wanted to preserve his support and win a war he probably shouldn’t have taken on.

Hitler’s way of deliberating was bad. He wanted outcomes he wasn’t smart enough to realize were incompatible. And by “smart enough,” I mean “willing to listen to people more expert than he.” Hitler’s rejection of his military experts’ advice is infamous, as is his firing anyone who disagreed with him.

What matters about Hitler, from the perspective of thinking about process, about the way an administration or leader deliberates, is how he decided. As Albrecht Speer said, Hitler sincerely believed himself to be a universal genius, and the paradoxical consequence was that he only allowed around him third-rate intellects. Hitler was obsessed with world domination and purifying the Germans. But he was even more obsessed with being the smartest person in the room, with having around him people who flattered him, with silencing dissent (on the grounds that it was disloyalty), with firing anyone who actually knew more than he did. He hired and fired on the basis of loyalty, not expertise.

That ended with people huddled in bomb shelters like the one in the photo.

When has it ended well?

Research on businesses says it doesn’t end well; I can’t think of a single historical example when it’s turned out well.

I’m making a falsifiable claim. I’m saying that Trump’s way of handling decision making is bad, and I’m using Hitler as an example.

When I pose this question to people who support the model of a “universal genius” who silences dissent, relies on his (almost always his) gut instinct, and who only get their information from in-group media, the response is always some version of “Hey, I’m winning—screw you for asking.” They say I’m biased for criticizing Trump, Obama was worse, abortion is bad. They say, in other words, because they like what they’re getting, they don’t care whether this has never worked out well in the past.

Guess who else thought that way.

What they don’t say is “here is an example of a leader who claimed to be a universal genius, who fired anyone who criticized him, who wouldn’t allow anyone in the room who was more an expert than he, who made every issue about him, who lied about big and small things, who used his power to reward people and states who were loyal to him and punish ones who weren’t, who openly declared himself above the law, and it worked out great.”

That’s because there is no such example.

In other words, they can’t come up with an example of a time when an administration that reasons that way has been successful. They are committed to a way that has never worked. They are committed to the way that people supported Hitler.

When Germany was finally conquered, 25% of the population thought it was right to have followed Hitler, and that he had been badly served by the people below him. 25% of the German population were so committed to believing that Hitler was their savior that no evidence could prove them wrong.

I’m not saying that Trump is Hitler.

I’m saying something much more troubling: I’m saying that the people who support Trump reason the way that people supported Hitler. I’m not talking about Trump. I’m talking about his supporters. I’m not saying they would have supported Hitler. I’m asking them to consider whether their way of supporting Trump is a good way to support a political figure.

This is two-part: can they give examples of times when this kind of support for this kind of leader has worked out well? And, can they identify the evidence that would persuade them their support for Trump is wrong? What is it?

And, if their answer is that there is nothing that would make them question their loyalty to Trump, and nothing that would persuade them to venture outside of the pro-Trump media, then they aren’t just admitting their political position is irrational, but they’re committing to a way of thinking about politics that has never ended well.

It wasn’t that long ago that that way of thinking about politics ended up with Germans huddled in concrete balls.

In another post, I mentioned that we don’t know what we don’t know.

This is the central problem in rational deliberation, and why so many people (such as anti-vaxxers) sincerely believe their beliefs are rational. They know what they know, but they don’t know what they don’t know. People have strong beliefs about issues, about which they sincerely believe they are fully informed because all of the places they live for information tell them that they’re right, and those sites provide a lot of data (much of which is technically true), and also provide a lot of information (much of which is technically true). But, that information is often incomplete—out of context, misleading, outdated, not logically related to the policy or argument being proposed.

There is a way in which we’re still the little kid who thinks that something that disappears ceases to exist—the world consists of what we can see.

I first became dramatically aware of this when I was commuting to Cedar Park, or Cedar Fucking Park, as I called it. I saw people talking on their cell phones drift into other lanes, and other drivers would prevent an accident, and the driver would continue with their phone call. They didn’t know that they had been saved from an accident by the behavior of people not on the phone. They thought that they were good at talking on the phone and driving because they never saw themselves in near-accidents. They never saw those near accidents because they were distracted by their conversation.

I have had problems with students who think they’re parallel-processing in class—who think they can be playing a game on their computer and pay attention to class—but they aren’t. We really aren’t as good at parallel-processing as we think. The problem is that the students would miss information, and not know that they had because, like the distracted drivers, they never saw the information they’d missed. They couldn’t—that’s the whole problem.

I eventually found a way to explain it. I took to asking students how many of them have a friend whom they think can safely drive and text at the same time—that, as they’re sitting in the passenger seat, and the driver is texting and driving, they feel perfectly safe. None of them raise their hands. Sometimes I ask why, and students will describe what I saw on the drive to Cedar Park—the driver didn’t see the near-misses. Then I ask, how many of you think you can text and drive safely? Some raise their hands. And I ask, “Do any of your friends who’ve been passengers while you text and drive think you can do it safely?”

That works.

For years, I’ve begun the day by walking the dogs up to a walkup/drivethrough coffee place (in a converted 24-hour photo booth—remember those?), and used to get there very early while it was still dark. There was one barista who didn’t notice me (the light was bad, in her defense). I would let her serve two cars before I’d tap on the window. She would say, “Be patient! I’m helping someone!” She sincerely thought that I arrived at the moment she noticed me, and immediately tapped on the window. It never occurred to her that I was there long before she noticed me.

When I talk to people who live in informational enclaves, and mention some piece of information their media didn’t tell them, they’ll far too often say something along the lines of, “That can’t be true—I’ve never heard that.”

That’s like the bad drivers who didn’t notice the near misses and so thought they were good drivers.

That you’ve never heard something is a relevant piece of information if you live in a world in which you should have heard it. If, however, you live in an informational in-group enclave, that you’ve not heard something is to be expected. There’s a lot of stuff you haven’t heard.

What surprises me about that reaction is that it’s generally an exchange on the internet. They’re connected to the internet. I’ve said something they haven’t heard. They could google it. They don’t; they say it isn’t true because they haven’t heard it.

That they haven’t heard it is fine; that they won’t google it is not. And, ideally, they’ll google in such a way that they are getting out of their informational enclave (a different post yet to be written).

In that earlier post apparently about anti-vaxxers, but really about all of us, I mentioned several questions. One of them is: If the out-group was right in an important way, or the in-group wrong in an important way, am I relying on sources of information that would tell me?

And that’s important now.

If you live in informational worlds that are profoundly anti-Trump, and he did something really right in regard to the covid-19 virus, would you know? To answer: he couldn’t have, or, if he did, it was minor is to say no.

And the answer is also no if you’re relying on the arguments that Rachel Maddow says his supporters are making, as well as on your dumbass cousin on Facebook. Unless you deliberately try to find pro-Trump arguments made by the smartest available people, you don’t.

If you live in a pro-Trump informational world, and Trump really screwed up in regard to the covid-19 virus, would you know? To answer: no, or perhaps there were some minor glitches with his rhetoric is to say no.

And the answer is also no if you’re relying on the arguments that Fox, Limbaugh, Savage and so on say critics of Trump are making, as well as the dumbass arguments your cousin on Facebook makes. Unless you unless you deliberately try to find arguments critical of Trump made by the smartest available people, you don’t.

People are dying. We need to know what we don’t know, and remaining in an informational enclave will make more people die.

You can’t know what you don’t know. You can’t know what you weren’t told. You can’t know what you didn’t notice.

You can’t know what you don’t know. You can’t know what you weren’t told. You can’t know what you didn’t notice.

A lot of people outraged about anti-vaxxers think they’re ignoring facts. But they aren’t. I’ve argued with them, and they have a lot of facts, and a lot of those facts are true. The problem isn’t in their facts, but in how they think about what makes a good argument. Anti-vaxxers are a great example of how not to think about having a good argument—one shared by a lot of people.

Their argument is: “We shouldn’t require that people get vaccines because [this vaccine] is bad because [fact].” And so they know that they’re right because they live in a world in which they are continually “shown” that they are right. They are given lots of facts (which might even be true) and lots of information about what their opponents believe (most of which is straw man). If you don’t drift into the world of anti-vaxxers, you don’t know that.

Just to be clear: I think anti-vaxxers are full of shit. I sincerely believe that anti-vaxxers believe they are truthful. And they also have a lot of facts, many of which are true. But their fullofshitness isn’t about whether they have facts, or whether they are truthful. It’s about their logic. It isn’t about whether they have facts, but about how they reason, and about the informational worlds they choose to inhabit.

Here’s an anti-vaxxer argument I’ve come across more than once. It’s something along the lines of, “If you look at the ingredients for this vaccine, you can see it has this ingredient, and, if you look up that ingredient on the internet, you can see that it’s really dangerous.”

That argument is a series of claims, each of which is factually true. It really does have that ingredient, and you really can look it up, and you really can see that it is harmful. The facts are true, but the logic is dumb.

If we step away from whether people have “facts” to how they’re arguing, then you can see that those claims don’t lead to each other.

Dihydrogen Monoxide (DHMO) is a notoriously dangerous chemical. It is responsible for thousands of deaths every year, and it’s in biological and chemical weapons. There’s a list here of its dangers, and they are many. So, if the logic of the argument above is good—this vaccine is dangerous because it has an ingredient that’s dangerous–, then the person making that argument has to support the claim that any medications containing DHMO are dangerous.

If it’s a bad way to argue in regard to DHMO, then it’s a bad way to argue about any of the chemicals in vaccines.

DHMO is water.

It’s a bad way to argue.

When I try to point this out to people, they often say something like, “But water is different. Water is okay—this stuff isn’t.” And they can’t understand that they’re arguing in a circle. They have an unfalsifiable belief. They believe what they believe because they believe it and can find supporting evidence. That’s motivated reasoning.

It doesn’t seem like a bad way to argue because people choose to live in worlds in which we only hear how great our beliefs are and how dumb the criticisms of our beliefs are. We don’t know that we’re getting a straw man. And we don’t know it because the most cunning (and damaging) versions of the straw man are something someone really said but edited, taken out of context, or not representative. So, for instance, a pro-vaccine article might point out that early vaccines were dangerous, and an anti-vaxxer could quote only that part, not making it clear that the comment was about the cowpox vaccine. Or, and I’ve had this argument, they quote someone associated with pharmaceuticals (such as Shkreli) and use that as proof that everyone involved with pharmaceuticals is a greedy villain who doesn’t really care about anyone’s health.

Once again, the claim (everyone involved with pharmaceuticals is a greedy villain who doesn’t really care about anyone’s health) is supported by facts I believe are true (I think most reasonable people would)—Shkreli really is a greedy villain, and he really was associated with pharmaceuticals. The facts are fine, but the logic is bad. If one person associated with pharmaceuticals can be taken to stand for everyone who advocates vaccines, then one person associated with anti-vax can be taken to stand for everyone opposed to vaccines.

And that should be the moment the person realizes it’s a bad way to argue, but they often don’t because their informational world is filled with dumb, hateful, and horrible things that “pro-vaxxers” have said. A person in the anti-vax world thinks it’s fair to take Shkreli to stand for everyone promoting pharmaceuticals because he is so much like all the other examples that slither through the anti-vax informational world. What that person wouldn’t know is that they are only seeing the most awful examples of the out-group, and they rarely (perhaps never) hear about bad behavior of in-group members.

They don’t know that they don’t know enough to have accurate stereotypes about the in- and out-groups. Because we can’t know what we don’t know (but that’s a different post).

Here I just want to point out that these two related problems (thinking we have a “good argument” just because it has true claims, and thinking it’s true because it confirms everything else we choose to hear) aren’t solved by looking for facts, or by asking ourselves if we’re reasoning rationally. And both of those ways of thinking about beliefs suck.

We can ask these questions:

• Am I open to persuasion on this issue, and, if so, what evidence would persuade me?

• If the out-group was right in an important way, or the in-group wrong in an important way, am I relying on sources of information that would tell me?

• Would I consider this an argument a good one if I flipped the identities in it? In other words, if the argument is “This thing [that I already believe is bad] is bad because [other claim]” would I be persuaded if the argument was “This thing [that I believe is good] is bad because [that same kind of claim]”?

That last one is hard for some people, so I’ll give some examples:

Let’s say that I, a fan of Hubert Sumlin, say, “Chester Burnette is a terrible President because he issues a lot of Executive Orders.” Would I be persuaded that “Hubert Sumlin is a terrible President because he issued a lot of executive orders”? If not, then I don’t really believe the logic of the argument I’m making.

If the answer to each of these questions is no, then regardless of how many facts I have, I have bad arguments.

57% of white Americans believe “that discrimination against whites is as big a problem today as discrimination against blacks and other minorities” (2) and 49% of Americans believe “discrimination against Christians has become as big a problem in America today as discrimination against other groups” (16, 77% of white evangelical Christians believe that, 17), It is a cliché in various circles that there is a “war on men,” and the organizers of “Straight Pride” events insisted that cis-het men (and, given that they often displayed Confederate flags—racists) are the real ones whose rights are under attack. Michelle Malkin and other have argued that there is a “war” on conservative speech, and Fox News positions itself as opposed to “mainstream media” (suggesting it is marginalized in some way).

The Congress elected in 2018 broke records in terms of diversity, yet the vast majority are still het, white, male Christians. 75% of Senators are men, as are 77% of members of the House. 78% of Congress is white, and only 10% are openly LGBTQ. 88% of Congress self-identifies as Christian. The 2019 list of Fortune 500 CEOs also broke records in terms of diversity, with 33 women (or 15%). 59 of the Fortune 500 and S&P 500 CEOs are non-white (around 12%). In 2017, the Republicans had all three branches of government; and both chambers in 32 states. 26 of US governors are Republican.

Fox News, relentlessly supportive of the Republican Party (and especially Donald Trump), had record numbers of viewers in 2019, “making it the top-rated basic cable network.” It is “the most trusted name in television news” (Berry and Sobieraj 111). Talkers Magazine in 2019 listed the top three “most influential talk show personalities” as the openly pro-GOP Sean Hannity, Rush Limbaugh, and Dave Ramsey. Christians are doing well, too. As Rachel Laser says, “Trump is conferring unparalleled privilege on one narrow slice of religion”–conservative white patriarchal self-described “evangelicals” (I think the term “fundagelical”—not a term I invented—is more accurate). Their mission is to remake the US government into a democracy of the faithful, in which their policy agenda is the only religious agenda to benefit from the notion of “religious freedom”—an agenda of homophobia, patriarchy, and racism. In short, the reins for government, economic, and cultural power are firmly in the hands of cis-het white Christian male Republicans.

Not just firmly, but disproportionately so: 65% of Americans self-identify as Christian, 49% are men, and 60% are white. In other words, Christian white men are over-represented in positions of power. 35% of Americans self-identify as conservative (26% self-identify as liberal), while the number that self-identify as Republican (29%) is about the same percentage that self-identify as Democrat (27%).

So why are they whining so much? Why do members of the disproportionately powerful groups see themselves as victims?

Ashley Jardina, in her extraordinary White Identity Politics, quotes a man at a rally for Trump: “If you just put everything aside and talk about it rationally, it’s not racism when you’re trying to maintain a way of life and culture” (21). It’s notable that he isn’t talking about economic power, but a way of life and culture—that is, his privilege. Jardina quotes Bill O’Reilly, who said,

“For a long time, skin color wasn’t really much of an issue, in the 80s and 90s we didn’t her a lot. Yeah, you always had your Farrakhans and your Sharptons. We always had those people but—Jackson—they were race hustlers [….] But now, whiteness has become the issue. [….] So if you’re a white American you are a part of a cabal that either consciously or unconsciously keeps minorities down. Therefore, that has to end and whiteness has to be put aside. That’s what the border is all about.[….] Let everybody in. [….] That would diminish whiteness because minorities then would take over [….] That’s what this is all about. Getting whiteness out of power.” (220)

Note that, again, this isn’t about jobs, disease, crime—it’s about whiteness. It’s about whether “whiteness” (by which O’Reilly means loyal Republican white Christian men) will continue to be able to dominate politically, economically, and culturally. My whole talk is summarized in that quote.

This argument, oddly enough, gives away the game—that we have “a way of life” in which whiteness is dominant, and people feel themselves in existential threat because conservative Christian white masculinity is not quite as hegemonic as it once was.

Noel Ignatiev’s formulation of whiteness emphasized the rhetorical and political deflective power of “whiteness” (an aspect lost in many current discussions of “privilege” such as “privilege walks”). Whiteness, he argued, is presented to some people as a “privilege” that invites people to hurt themselves in material ways—good wages, job security, reasonable healthcare, good public schools, good roads—in order to get the “privilege” of being on the good side of American racism. Once someone has been invited to climb into whiteness, they are likely to be very protective of the privileges of whiteness; they are not only drawn to kicking the ladder out from behind them (that is, support abandoning the very policies and processes that enabled them to get to where they are), but to be among the most vocal and active opponents of the people who materially look very much like them (the Irish hating on other Irish, people on public assistance hating on other people on public assistance, second-generation immigrants hating on the latest group of immigrants). Ignatiev’s argument is that the invitation to the privilege of whiteness depoliticizes politics by deflecting discussion away from working conditions, infrastructure, social safety nets to whether your privilege is threatened.

Research in in- v. out-group relations makes it clear that people are willing to hurt themselves in order to keep an out-group from gaining. In various studies, if people are asked to choose between an outcome that gives the in-group and out-groups the same amount, they will choose to take a hit just in order to hurt the out-group more. Sometimes called “Vladimir’s Choice,” it is “the tendency for people to choose to disadvantage others, even when doing so comes at the cost of disadvantaging themselves” (Sidanius et al. 257, see also Koomen and van der Pligt 122).

As long ago as 1941, the deeply-problematic (aka racist, although sometimes categorized as moderate white) W.J. Cash noted that race-baiting was effectively used to keep poor whites from engaging in the political action that would have meant sense materially. Giving poor whites “white privilege” (also known as herrenvolk democracy) meant they didn’t demand good jobs, good schools, good roads, good healthcare because the system guaranteed them that they could feel a kind of identification with the richest white person (even if it was the one who screwing them over in material ways). LBJ famously said, “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”

One irony of the political power of that rhetorical invitation to whiteness is that it involves the simultaneous claim that whiteness is ontologically grounded and a new group can see themselves as white. That new group can see itself as only now and yet always already white. This material and political persuasion is fundamentally rhetorical. People are persuaded to depoliticize policy questions—instead of arguing about our rich and varied policy options in terms of questions like feasibility, solvency, unintended consequences, we frame policy questions in terms of in-group benefit and loyalty (and, sometimes openly, hurting the out-group).

Jardina argues that “white identity […] is a product of the belief that resources are zero-sum, and that the success of non-whites will come at the expense of whites” (268). I would modify that to say that it isn’t a question of resources, but of privilege—that people who strongly identify as white, and who feel threatened, don’t feel threatened in material ways, but in terms of privilege. They see, probably correctly, that white privilege is a zero-sum, and the more that whiteness is not privileged, the more whites lose…privilege. As Jardina says, “When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression” (21).

Jardina argues that this anxiety about white privilege is the consequence of increased immigration of non-whites allowed by Reagan’s immigration policies, an explanation that assumes a material cause. But whiteness has always been threatened by the immigration of “non-whites” (or non-WASPs), as early as the immigration of Irish and German Catholics in the first part of the 19th century. Whiteness has long maintained its privilege by giving white cards to another group—a group always defined against African and Native Americans (and, until recently, against Jewish and Asian Americans—this seems to be changing, in complicated ways).

My point is that Ignatiev’s argument—that the rhetorical and political invitation to whiteness is a way of neutralizing a potentially radical opponent—is something we’re seeing now. The inclusion in whiteness is how people forget class, it’s how people redefine our own ancestors. More important, it’s how people are persuaded to oppose, passionately, policies that would help them.

Jonathan Metzl’s heartbreaking chapter about sick white men in Tennessee who opposed the expansion of Medicaid or any aspect of “Obamacare”—policies that would have helped them—shows that they did so because they believed that those policies would have enabled “a lot of people that’s not sick…to use the shit out of it, and then when somebody really needs it, they ain’t there for you to get” (Dying of Whiteness 149). They were willing to sacrifice themselves just to make sure an out-group didn’t get benefits.

People can be persuaded set themselves on fire just to make the out-group uncomfortably warm. When an out-group is stereotyped as lazy, and that out-group is getting the same benefits as the in-group, the in-group will reject the benefits. A famous instance of this is the refusal of working-class whites in many areas to join unions, if the unions would have non-white members who would also benefit from union negotiations. But, it’s also, as Metzl observes, a reason that the poor white men he studied in Tennessee will refuse Medicaid—because of the perception that doing so would benefit an out-group whom they saw as lazy and parasitical. These men were making Vladimir’s choice.

How are people persuaded to hate some group so much that they will set themselves on fire in order to make the out-group uncomfortably warm? The short answer is that they are persuaded that they are in a zero-sum apocalyptic battle with the out-group, that the out-group benefitting in any way is yet one more step toward the extermination of the in-group. Their greatest fear is that the previously marginalized out-group will treat them as badly as they treated that out-group.

This is an old argument, the “wolf by the ears” argument that Thomas Jefferson made about African Americans: treatment of slaves had been so bad that it was like having a wolf by the ears. If the US freed slaves, they would turn on whites in a race war. This was the argument made in such different places as a Supreme Court decision about Japanese internment, arguments against releasing innocent people from GITMO, defenses of displacing Native Americans.

The short answer is that they get radicalized by their media of choice.

The first step of radicalizing an audience is to say that we are facing an existential threat. Sometimes the threat is that everyone is threatened; sometimes it’s just the in-group. And here I have to point out that radicalizing an audience, at least to some extent, is not always bad. Sometimes we are facing an existential threat. We can have democratic deliberation and existential threat. In this case, however, the in-group’s existential threat is the loss of privilege, as though people cannot be white and equal.

The second step is to say that this existential threat has an obvious cause, and an equally obvious solution. This is the point at which media say we need to stop arguing about our policy options and go for this one because it is the only right option. This step toward radicalization is an explicit rejection of democracy and democratic deliberation.

The third step follows from the previous two. If the solution is obvious, why are some people unpersuaded? This step says that our complicated world is really just a zero-sum battle between two groups. The third step appeals to our tendency to frame issues in terms of in- and out-groups. We are all prone to categorize people we meet—she’s a Missouri Synod Lutheran, so she must be a Calvinist; he’s got a neck beard, so he must be a douche; they’re from Alabama, so they must racist; he’s black, so he must like rap; she’s a Sanders supporter, so she must be a jerk; he’s a Biden supporter, so he must be a tool of corporate America. Those initial impulses toward categorizing are inevitable, and not necessarily harmful, if they’re open to revision.

The third step toward radicalization is to keep those categories—stereotypes, really—safe from disproof, and that is best done by framing the characteristics of our mental stereotype as essential. What I’ve noticed about stereotypes—the racist Southerner, good-at-math Asian, caring female teacher, hardass white male teacher, lazy POC, corrupt politician—is that, for many people, they exist in a weird space of simultaneously ontologically-grounded and non-falsifiable Platonic forms. Although those beliefs can be shown to “true” by giving evidence, they aren’t shown to be “false” if the evidence turns out to be false or irrelevant, or if there is counter-evidence. All counter-examples are instances of “no true Scotsman.”

Crucial to this step is the assumption (and talking point) that there is no good-willed disagreement of any kind—disagreement, dissent, or even skepticism about the in-group ideology/policy—is not a legitimate point of view to be considered, but proof that the person disagreeing is Them. That they disagree is proof that they are Them, or a stooge of Them. This step is not just a complete rejection of democratic deliberation, but an active move toward fascism (or some other kind of authoritarianism).

These three steps—there is an existential threat; the solution is obvious; only They disagree with us—lead neatly to the fourth step: purifying the in-group. At this point in radicalization, we’re in a world grounded in a lot of claims that a few minutes of sensible googling would show to be wrong: there is never only one possible policy option, the entire world of political positions is not usefully reduced to us v. them.

We are so deeply immersed in a culture of demagoguery, that, when I make this argument, people often say, but there are evil groups. And there are. But, even if we agree that there is an existential threat doesn’t mean there is only one possible response. We really shouldn’t disagree as to whether we should fight Nazis and fascists, but it’s fair to disagree about the best way to do that. We have a lot of options, and it might be most effective for us to adopt a lot of different strategies at the same time. Radicalization, however, says that there is only way to fight Them, and it is to for all in-group members to be more purely loyal to the in-group, committed to purifying the in-group.

The tendency to believe that the only response to existential threat, failure, or uncertainty is a purification of the in-group is well-documented (Koomen and Van der Pligt, and Hogg et al.). This call for purity is always a call for remaining pure in your sources of information, and that’s the fifth step in radicalization: inoculation against dissent, disagreement, disconfirming evidence. If in-group members who have been radicalized this far look at information from other sources—even non-radicalized in-group sources—then they might realize that they’ve been lied to. The more extreme that in-group propaganda becomes, the more vulnerable it is to disproof, and the solution is to persuade its audience that they shouldn’t even look at other media, except in radical in-group media’s abridged, edited, and sometimes actively falsified form.

Inoculation is the rhetorical move of giving your audience a weak version of an argument they will later confront, and it’s something people in rhetoric should study much more. It’s how far too much of our media works (and pretty much all political youtube videos). Propaganda doesn’t work if it looks like what people think propaganda is—what They listen to. Propaganda is most effective when it looks “fair.”

Oddly enough, then, radicalization only works if it looks as though it’s being “fair” to “the other side,” if it looks “objective” and “unbiased.” And, so, here we are at the paradoxical situation that radicalizing an audience has to look as though it isn’t radicalizing, but being “objective.” This step in radicalization is greased by how bad our cultural discourse is about “objectivity” (a slide greased by how far too many fyc courses talk about “objectivity”). Even in academia, the whole discussion of “objectivity” is muckled by binaries. I want to set aside that hobby horse, however, and go back to the question of radicalization. Here I’ll just say that we shouldn’t be looking for proof, but disproof.

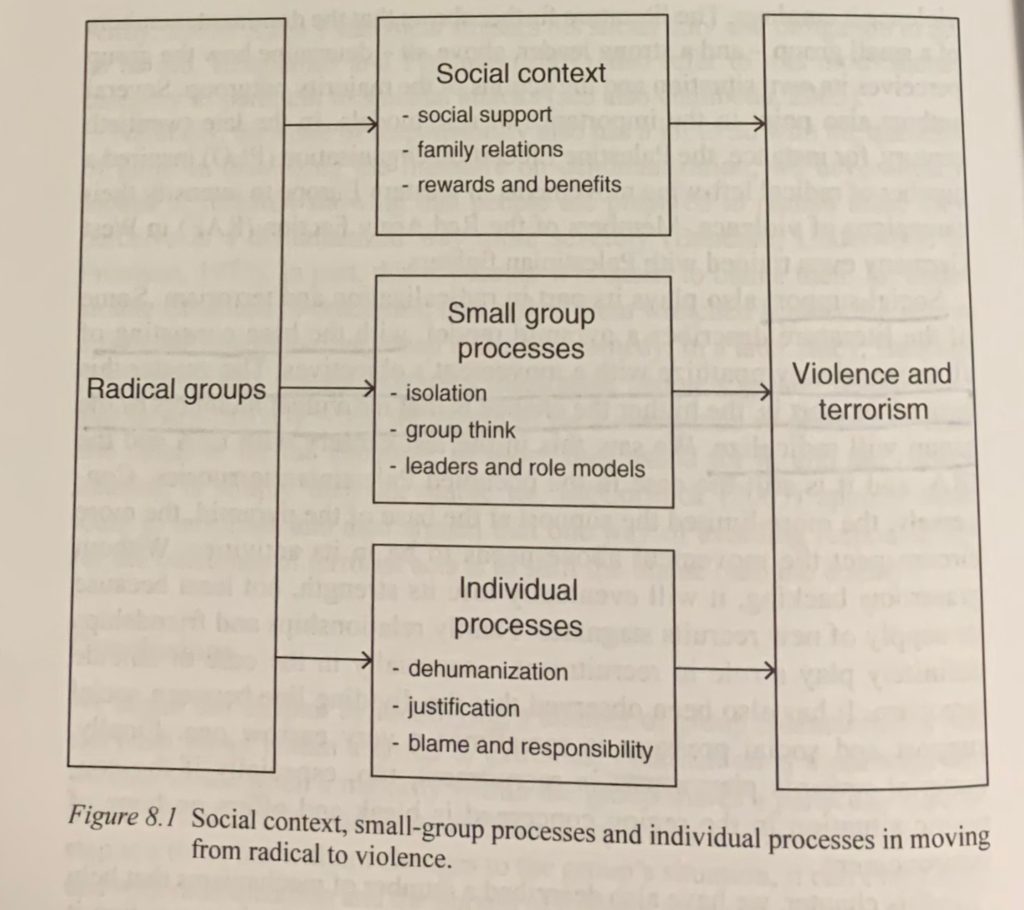

Willem Koomen and Joop van der Pligt, in their book The Psychology of Radicalization and Terrorism, argue that radical groups operate most effectively within certain social contexts (such as relative deprivation) and to the extent that they can foster the ideological processes that rationalize (even seem to make necessary) intergroup violence (or the support of violence).

The first of those processes, isolation, Koom and ven der Pligt describe in terms of groups like the Weathermen that physically isolated recruits, but I want to suggest that we should think of the rhetorical process of inoculation as functionally the same kind of isolation. According to Berry and Sobieraj (The Outrage Industry), as well as Benkler et al. (Network Propaganda), much of our current media spends as much time trash-talking “the other” as it does promoting its own side. The point of all that trash-talking is that the “other” media is dangerous, corrupting, and should be avoided.

Research is clear that “cross-cutting” in terms of political discourse—talking to people who disagree, reading or viewing opposition points of view (and not hate-watching)—is beneficial. Inoculation prevents precisely that approach; that’s what it’s intended to do.

That isolation enables group think, a phenomenon that leads to ingroup amplification: “the convictions of moral superiority, in combination with extreme forms of us-versus-them thinking helps to legitimize violence against all adversaries, including innocent children” (Koomen and van der Pligt 179). And here I’m thinking of all those arguments about why putting children in cages is moral.

I mention that political position, but this is a process, facilitated by media, that can happen anywhere on the political spectrum (think anti-vaxxers, flat earthers).

Jardina, as mentioned before, argues that the rise of white identity politics is the consequence of increased immigration under Reagan, largely because of the timeline, but I’m dubious. That timeline also fits the rise of hate-talk radio and radicalizing cable “news,” and social media—including youtube—fuels a cycle of self-selection, self-censorship, and self-radicalization.

Hanna Pitkin once said that what she called “free citizenship”—what I think might more usefully called “responsible political action”—requires “the ability to fight—openly, seriously, with commitment, and about things that really matter—without fanaticism, without seeking to exterminate one’s opponent” (266). My argument is that, through a process of rhetorical radicalization, far too many sites of political discourse not only depoliticize politics, but seriously limit and sometimes completely stifle political discourse itself. Instead of fighting, we exterminate.

So what do we do? Make better media choices. As Benkler et al. show, not all media are the same. While almost all media is driven by the profit motive to engage in damaging frames for politics: us v. them (in other words, zero-sum), elections as horse races, the kind of sloppy psychologizing that displaces policy argumentation with motivism, some media are better than others at fact-checking, issuing corrections, avoiding disinformation campaigns (see especially 381-387). But, as they say, “The pessimistic lesson of our work is that there is no easy fit for epistemic crises in countries were a political significant portion of the population does occupy a hyperpartisan, propaganda rich environment” (386).

Yesterday, the UT University Writing Center (a division of the UT Department of Rhetoric and Writing) staff meeting was, for the second week in a row, about planning strategically for okay- to worst-case scenarios regarding not just the coronavirus, but the ways that UT might respond. At this meeting we had the Program Coordinator from Athletics, as well as the Program Coordinator for the Digital Writing and Research Lab (our sister in the DRW).

As colleagues at various institutions have said, the notion that there is an obvious response that universities should have and aren’t having is nonsense. There is no obviously right solution (although, I’d say, there are some obviously wrong).

It was a discussion that involved worrying about undergraduates in precarious financial situations who need to keep working, staff and students who are living with or caring for people in the high-risk category, the needs of students to continue to get support for their writing, and legitimate concerns about overwhelming existing technology and whether we’re—as a university—shifting to a system that will have a disparate impact on students with limited financial means.

As the DWRL Program Coordinator pointed out, if everything shifts to online—classes, consultations, office hours—then students will suddenly find themselves devouring data, and that’s pricey. Not all students have computers, nor do they all have wi-fi in their homes, and, if they do, they don’t necessarily have unlimited data plans. Shifting to online classes disproportionately hurts students who don’t have the means to go out and buy a laptop or pay for a better dataplan.

Closing campuses has repercussions that disproportionately hurt marginalized students. If classes are cancelled, students on financial aid of various kinds might have to pay money back, students on education visas might find themselves in precarious situations, students in university housing who don’t have the money to fly back home (or don’t have a home to which they can fly back) are on the street.

There is a saying, “If white people get a cold, black people get pneumonia.” How some universities are handling the coronavirus is an unhappily apt example of that saying. It isn’t necessarily just black v. white, but disadvantaged technologically v. highly advantaged. If a university shifts to online teaching, cancels classes, or closes campuses, rich students will be fine. Shifting to online classes is non-trivial to wealthy students, but potentially a disaster for students whose precarious financial situation means they’re on limited data plans, and closing campuses is even worse for them.

So, universities that are concerned about what are supposed to be American values—inclusion, social mobility, fairness—aren’t immediately shutting down. And that is not an obviously bad decision. They’re trying to think things through. UT is moving more slowly than other universities on all this, and today announced an extended Spring Break—one that will enable faculty and graduate student instructors to redesign classes for online delivery–but I sincerely believe that it is doing so because administrators are meeting constantly and really trying to balance various legitimate needs, including questions of the digital divide. Our sister unit, the DWRL, is looking into opening its classrooms so that students who might be prevented from participating in online classes because of their precarious financial situation can have full access. But it will take them time to figure out if that can be done in a way that is also safe.

One of my direct reports (who lives with someone high-risk) had an email exchange with HR about how to institute a telecommuting agreement, and the response was reasonable, advocating flexibility on the part of the unit. My Chair is completely supportive of flexible and sensible policies for my unit, giving me helpful information about where things are headed (helpful information zie has been given). I’m saying that I feel enabled by my chair, HR, and my university to respond as ethically as possible to this situation.

I’m not saying that every university has responded well, nor that my university’s response has been perfect. Hell, my response has been reactive. I’m in my sixth year directing the UWC. I should have put in place a pandemic plan my first year. Many of the policies we’re enacting I should have put in place just because of the flu.

Yes, the university should have had a pandemic plan in place, and the technology to support it, but so should I. My university didn’t. I didn’t. When the smoke clears, I will almost certainly be unhappy about how my university responded, but, and this is the point, it might just be that my university’s response was sensible given constraints of which I am unaware. A person looking at this situation, unaware of the implications of shutting down a university for international students, might believe there is only one right answer.

The seed of authoritarianism and demagoguery is the premise that situations aren’t complicated, that there is an obviously correct course of action, and that anyone who opposes that obviously correct course of action (doing this thing, supporting this political figure, enacting this policy) does so because they’re corrupt, biased, or stooges to corrupt media.

I love me some agonism. I think we should all argue vehemently, passionately, and reasonably for our positions. I don’t think that arguing vehemently, passionately, and reasonably for our positions and being willing to settle on better rather than best are mutually exclusive positions. Change happens when there are people who agree to make things better and others who point out that this “better” could be better yet. Both positions are important.

No university is responding in the perfect way, but some are responding in terrible ways. I am tremendously proud of how my university is responding.

I should begin by saying that I think there are good reasons for supporting Sanders, and many of his supporters make good arguments for their preferring him over other candidates. But, I also think there are good reasons for supporting other candidates, and for not supporting Sanders. Some of those good reasons involve people having different priorities from one another, different assessments of risks, or different predictions about various uncertainties about our political situation. That I feel certain I’m right is not the same as having the only legitimate political position.

I should begin by saying that I think there are good reasons for supporting Sanders, and many of his supporters make good arguments for their preferring him over other candidates. But, I also think there are good reasons for supporting other candidates, and for not supporting Sanders. Some of those good reasons involve people having different priorities from one another, different assessments of risks, or different predictions about various uncertainties about our political situation. That I feel certain I’m right is not the same as having the only legitimate political position.

I’m not saying all arguments are equally valid, or it’s all just personal preference, or there’s no difference among the candidates. I am saying that intelligence and reason are not restricted to only one candidate’s supporters. Further, I’m saying that insisting that there is only one reasonable position to have, that my political beliefs are the only rational beliefs, and that anyone who doesn’t support my candidate does so because they are corrupt, stupid, biased, or the stooge of a corrupt entity is engaging in a damaging form of demagoguery. It is damaging to democracy.

People are sharing this post as though it’s a smart argument, and it’s really objectionable berniesplaining. And, let’s start with saying that if berniesplainers explain in comments that their telling me that I have never seen berniesplaining, but I have simply misunderstood my own experience, they are berniesplaining.

Mansplaining is when a man explains something to a woman assuming she is ignorant, and she’s actually quite well-informed, perhaps an expert. It’s particularly irritating when a man explains to a woman what it’s like to be a woman, when he tells us that we don’t really understand our own experience as women, and that he knows what we should want, what policies we should support, because our own understanding of our experience is biased and irrational, but his is unbiased, rational, and objective. Whitesplaining is when a white person tells POC that they don’t really understand their experience as POC because POC are biased, irrational, and subjective, but this white person really knows how they should think, behave, vote.

Bernisplaining is when Sanders supporters explain to people who don’t support Sanders that any position other than supporting Sanders doesn’t come from a legitimate difference of opinion, or a rational assessment of the situation, but from being corrupt or a stooge of corruption. Berniesplainers explain that the people who disagree with them don’t understand our own political views, needs, or positions.

Everything that is wrong about Sanders’ rhetoric is in this post. The article says that Sanders’ showing on Super Tuesday–that a lot of people didn’t vote for him–“doesn’t mean that voters are mindless robots taking orders from above”(why would that even need to be said unless there are people in the article’s audience who would give that explanation?), but because anyone who voted against Sanders did so because they voted on the basis of a cognitive bias. ORLY?

In other words, had they not been relying on a cognitive bias, they would have voted for Sanders. So, there is no good reason for supporting anyone other than Sanders. And I am incredibly tired of bernisplainers beginning every argument from that assumption.

[Speaking of cognitive biases, that article is a great example of two cognitive biases: asymmetric insight, and in-group favoritism.]

More important, leftists are supposed to reject the notion that we are all the same, that there is some position from which unmediated perception of the truth is easy. We are supposed to be the group that says that people have genuinely different experiences, that the world is uncertain, and disagreement is okay.

Yes, not all Sanders supporters assume that they are the only people with a legitimate point of view, and attacks on Sanders can be patronizing and just plain stupid, and, as Jamieson showed pretty clearly, much of the intra-group hostility in 2016 was ginned up by pro-Trump forces. And it’s in Trump’s best interest to have potential Dem voters hate each other more than we want to get him out of office.

But this article–one that said that people who voted for anyone other than Sanders did so because they were dupes to a cognitive bias–was not a meme created by a pro-Trump troll. And Corey Robin shared it. This is not a fringe pro-Sanders’ position. This patronizing, dismissive, and anti-democratic attitude is central, not just to Sanders, but to the left.

We should be better than this.

Not all Sanders supporters are berniesplainers. But all berniesplainers do not actually support democracy. And that’s a problem. Democracy is premised on the notion that disagreement is productive because people really disagree, because as various people have pointed out, advocating a political policy is a leap into the unknown. Democracy presumes that we have genuinely different and legitimate values and interests.

To the extent that pro-Sanders rhetoric says that anyone who doesn’t support Sanders only does so without legitimate reasons—they do so because they’re falling prey to a cognitive bias, they’re stooges to the DNC or media—is the extent to which pro-Sanders rhetoric is patronizing, arrogant, and anti-democratic. It’s berniesplaining.

Democracy is premised on the notion that no individual or group (or faction, as the founders would have said) has God speaking in their ear. The founders did intermittently argue that some individuals reasoned from a position of universal knowledge, and leftists are supposed to reject that epistemology.

Democracy is about acknowledging that people disagree because we really disagree. There is not just one solution that is obvious to all right-thinking people. Democracy presumes that there is legitimate disagreement. People who think there is not legitimate disagreement, regardless of where they are on the political spectrum, are anti-democratic. They are not leftists. They are political and epistemological narcissists.

Why all the Warren/Sanders hate?

Why all the Warren/Sanders hate?

Imagine that the politicians Chester and Hubert agree that there is a squirrel conspiracy to get to the red ball. Chester thinks that little dogs are part of the squirrel conspiracy; Hubert thinks they aren’t. The squirrels would stir up as much shit as possible between Chester and Hubert about little dogs, an issue that is actually much less important than the squirrel issue.

Squirrels would create social media accounts promoting memes and snarky posts about how Hubert was nice to a little dog, about how Hubert supporters don’t have legitimate reasons for their support of him (they like him because he has a cool coat, he petted a puppy), but Chester supporters have good reasons for supporting Chester. Squirrels would work to create a wedge between Chester and Hubert supporters, since the political success of either of them would be disastrous for squirrels.

There are various ways of doing that, but everything the squirrels would do would involve keeping Chester and Hubert from working together. If Chester and Huber work together, regardless of the issue of the little dogs, the squirrels are toast.

A pro-squirrel media campaign in a balkanized media sphere would condemn Chester and Hubert as anti-squirrel in all the pro-squirrel media. What would the squirrels do in the anti-squirrel media world?

They would try to get a purity argument between Chester and Hubert, one that would keep them from working together.

That happened. In the early 19th century, Irish- and African-Americans had similar material interests—there was no social safety net, there was racism (Catholicism was framed as a race), and abusive working conditions for both groups. It would have been sensible for Irish- and African-Americans to work together, but they didn’t. They didn’t because—to make a complicated situation simple—Jacksonian Democrats (who needed a base of voters in a non-slaver state to support slavery) put a wedge between the Irish- and African-Americans, and that wedge was the ability to invite the Irish-Americans to believe themselves as essentially better and different from African Americans.

The original sin of political deliberation is that we reason from identity, rather than applying principles across identity. And the wedge enabled the Irish to feel good about themselves because they weren’t African. That’s also how the planter class in the South prevented unionization—segregation helped keep poor whites poor because it ensured they wouldn’t join forces with poor African Americans.

It makes perfect sense that people would create a wedge issue to keep potential allies apart, but why do we fall for it?

Sure, the squirrels would create memes intended to make Chester and Hubert supporters so angry with each other that they won’t collaborate, but why would Chester and Hubert supporters share the memes, posts, and links that help the squirrels?

We fall for it because people are always more worked up about heretics than infidels. In theory, we hate infidels more than heretics, but in practice, that isn’t what happens. It has to do with a cognitive bias about decision-making.

If we are faced with a decision between two pretty similar things, we are likely, once we’ve made the decision, to exaggerate the differences between the two in order to make us feel better about the decision we’ve made. Ambiguous decisions are more threatening to our sense of self than clear-cut ones because they are the ones we can get wrong. Our need to make ourselves feel that we’ve made the right decision means that we will not acknowledge that we were even unsure, let alone that the other option might be more or less equally good.

Our hostility toward infidels doesn’t raise any uncertainty; that we have chosen between two similar choices does. When people are presented with uncertainty, we have a tendency to retreat to purity and in-group loyalty. We pass along the memes planted by trolls because they tell us that our decision is entirely right, and that the solution is in-group purity. And that feels good.

What Trump needs, as he needed in 2016, is to get potential Dem voters to get into purity fights with one another. What his considerable Russian support is doing, as it did in 2016, is to persuade large numbers of potentially anti-Trump voters to stay home if they don’t get their candidate. And they way to do that is to make Dems angrier with each other than they are with Trump, and it’s happening through memes that say things like, “A friend says she supports Chester because Chester wears such a great sweater, but I support Hubert because he’ll give us all real protection against the squirrels.”

[Since I crawl around pro-Trump sites, I can say that is exactly their strategy there too—Dems support policies out of fee-fees but Trump supporters are interested in real solutions for real problems.]

The more that Hubert supporters share that meme, the more they help the squirrels.

I’m not saying that the differences between Hubert and Chester are trivial—they’re real, and they matter. And we should argue about those differences, instead of framing the other side as being irrational and corrupt. I’m saying that, whatever our differences, sharing memes about how awful the other is ensures that neither Hubert nor Chester will succeed.

Obviously I’m talking about Warren and Sanders, but I’m also not—I’m talking about all the other times that potential allies were and are deliberately wedged apart. We can disagree with each, and we can believe that other people are backing the wrong candidate, but we shouldn’t hate other people for voting differently from us.

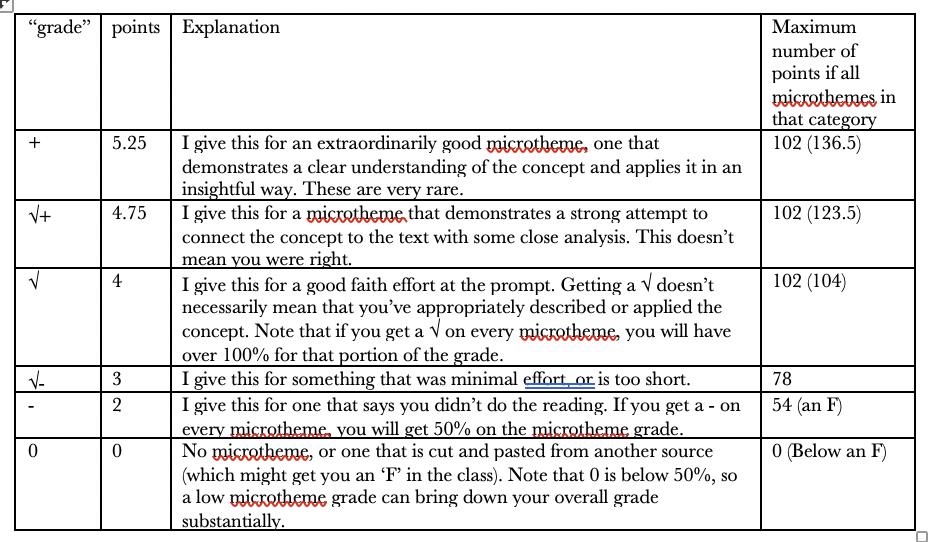

Over time, I have evolved to having students submit “microthemes” (the wrong word) before class, and I use them for class prep. I keep getting asked about that practice, so this is my explanation.

Here’s what I tell students in my syllabus.

———

Microthemes. Microthemes are exploratory, informal, short (300-700 words) responses to the reading (they can be longer if you want). They have a profound impact on your overall grade both directly and indirectly; doing all of them (even turning in something that says you didn’t one) can help your grade substantially. Since the microthemes are on the same topics as the papers, they also serve as opportunities to brainstorm paper ideas.

The class calendar gives you prompts for the microthemes, but you should understand those are questions to pursue in addition to your posing questions. That is, you are always welcome to write simply about your reaction to the reading (if you liked or disliked it, agreed or disagreed, would like to read more things like it). Students find the microthemes most productive if you use the microtheme to pose any questions you have–whether for me, or for the other students. They’re crucial for me for class preparation. So, for instance, you might ask what a certain word, phrase, or passage from the reading means, or who some of the names are that the author drops, or what the historical references are. Or, you might pose an abstract question on which you’d like class discussion to focus. I’m using these to try to get a sense whether students understand the rhetorical concepts, so if you don’t, just say so.

A “minus” (-) is what you get if you send me an email saying you didn’t do the reading; you get some points for that and none for not turning one in at all. So failure to do a bunch of the microthemes will bring your overall grade down. If you do all the microthemes, and do a few of them well, you can bring your overall grade up. (Note that it is mathematically possible to get more than 100% on the microthemes—that’s why I don’t accept late microthemes; you can “make up” a microtheme by doing especially well on another few.)

Microthemes are very useful for letting me know where students stand on the reading–what your thinking is, what is confusing you, and what material might need more explanation in class (that’s why they’re due before class). In addition, students often discover possible paper topics in the course of writing the microthemes. Most important, good microthemes lead to good class discussions. The default “grade is √, except for ones in which you say that didn’t do the reading, or check plusses, plusses, or check minus. (So, if you don’t get email back, and it wasn’t one saying you hadn’t done the reading, assume it got a √.)

If you get a plus or check plus (or a check minus because of lack of effort), I’ll send you email back to that effect. (I won’t send email back if it’s a minus because you said you didn’t do the reading—I assume you know what the microtheme got.) If you’re uncomfortable getting your “grade” back in email, that’s perfectly fine—just let me know. You’ll have to come to office hours to get your microtheme grade. You are responsible for keeping track of your microtheme grade. There are 26 microtheme prompts in the course calendar; up to a 102 will count toward your final grade. There are five possible “grades” for the microthemes [the image at the top of this page].

Please put RHE330D and micro or microtheme in the subject line (it reduces the chances of the email getting eaten by my spam filter). Please, do not send your microthemes to me as email attachments–just cut and paste them into a message. Cutting and pasting them from Word into the email means that they’ll have weird symbols and look pretty messy, but, as long as I can figure out what you’re saying, I don’t really worry about that on the microthemes. (I do worry about it on the major projects, though.) Also, please make sure to keep a copy for yourself. Either ensure that you save outgoing mail, or that you cc yourself any microtheme you send me (but don’t bcc yourself, or your microtheme will end up in my spam folder).

=========

I find that I can’t explain microthemes without explaining how I came around to them.

I have three degrees in Rhetoric from Berkeley, for complicated reasons, none of which my ever involved deciding at the beginning of one degree that I would get the next. I always had other plans. And, for equally complicated reasons, I ended up not only tutoring rhetoric but acting as an informal TA (what we now call a Teaching Fellow) for rhetoric classes at some point (perhaps junior or senior year). And then I was the TA (a person who grades something like 3/5 of the papers and taught 1/5 of the course—a great practice) for two years, and then the Master Teacher (graded 2/5 of the papers and taught 4/5 of the course). Berkeley, at that point, was a very agonistic culture, and so “teaching” involved waking into class and asking what students thought of the reading, I was just a kind of ref at soccer game.

The disadvantage of all that time at one place and in one department was that I was very accustomed to a particular kind of student. Teaching rhetoric at Berkeley at that moment in time (rhetoric was not the only way to fulfill the FYC requirement and drew the most argumentative students) meant managing all the students who wanted to argue. And, given my Writing Center training, I spent a lot of time in individual conferences. My teaching load as a graduate student was one class per quarter.

That training prepared me badly in several ways. First, it was a rhetoric program, and the faculty were openly dismissive of research in composition. Second, I was only and always in classrooms in which the challenge was how to ref disagreement. Third, I adopted a teaching practice that relied heavily on individual conferences.

I went from that to teaching a 3/3 (or perhaps 3/2—I was always unclear on my teaching load) in the irenic Southeast. Students would not disagree with each other—if they had to, they would preface their disagreement with, “I don’t really disagree but…” In an irenic culture, people actually disagree just as much as they do in an agonistic one, but they aren’t allowed to say so.

Granted, we can never get students to give us some weird kind of audience-free reaction to the reading (if there is such a thing), but I had lost the ability to get a kind of almost visceral reaction to the reading, a sense of the various disagreements that people might have. I also didn’t have the time to meet with students individually as much.

I tried various strategies, such as students keeping a “sketchbook” (I can’t remember who suggested that), in which students responded to the reading, but I couldn’t read the book (since, in those days, it was a physical book) till after class, by which time it was too late for me to respond to what they’d said. But I did notice that students’ responses to the reading were more diverse than what ever happened in class. For one thing, students writing to me would say things they wouldn’t say in front of class.

Sometimes too much so. There was a problem with students telling me more about how the reading reminded them of very private issues. At some point I tried calling them “reading responses,” but that name flung students too often in the opposite direction, and they just summarized the readings.

I moved on to a place and time with more digital options—discussion boards, blogs—and found that they were great in lots of ways. Introverts who won’t talk in class will post on a blog, but there was an issue of framing. In discussions, of any kind, the first couple of speakers frame the debate, and future speakers generally respond from within that frame. So, as opposed to the “sketchbooks,” the blog posts were dialogic rather than diverse (although there weren’t as many plaints about a romantic partner). And even I recognized that a student could easily fake having done the reading, simply by piggybacking on other posts. The discussion board got me no useful information about how my students had reacted to the reading.

“Reading responses” was too private, but blogs were too much prone to in-group pressures.

I honestly don’t know where I found the term “microthemes,” and it’s still wrong (although less wrong than it used to be). Were I to do my career over, I would find a different term, but I don’t know what it would be.

The problem is that it has the term “theme” in it, and so students who have been trained to write a “theme” try to write a five-paragraph essay. Since fewer high school teachers ask for themes, this problem seems to be dissipating.

There are a lot of models of what makes for good teaching, and one is that a good teacher has students engage with each other—a good teacher is the teacher I was at Berkeley, just letting students argue with each other, and acting as a ref at a soccer game. And, to be honest, that was fine at Berkeley, because, while racists and misogynists and homophobes might have whined (and did) that people disagreed with them, people disagreed with them. Their whingeing was that someone disagreed with them.

It got more complicated in an irenic culture, when students didn’t feel comfortable disagreeing with anything. And, by the time I’d found about the disagreement, it was hard to figure out how to put into the class (I learned that you do it by your reading selections, but that’s a different post). The irenic culture meant that, if a student said something racist, other students didn’t feel comfortable saying anything about it (especially if the racist thing was within the norms of what I always think of as “acceptable racism”).

Behind all of this is that we are at a time when there is a dominant and incoherent model of what makes good teaching: it is about having a powerpoint (meaning you aren’t listening to what these students need, and you’re transmitting knowledge you already think they know) and having discussion in class in which all student views are equally valid.

That model is fine for lots of classes, but it’s guaranteeing a train wreck if you’re teaching about racism, or any issue about which a teacher is willing to admit that racism might have an impact. Since we’re in a racist world, asking that students argue with one another as though their positions are equally valid, when racism ensures they aren’t equally valid, is endorsing racism.

Yet, in a class about racism, it’s important to engage the various forms of racism that are plausibly deniable racism. Most racists don’t burn crosses or use the n word, but they make claims that they sincerely think aren’t racist. As I’ve said, this is rough work, and it really shouldn’t be on the shoulders of POC—white faculty should take on the work of explaining to white racists who think they aren’t racist that they are.

If we think of the discursive space of a class as the moment of the class, then this is almost impossible to do, and it’s racist to think that non-racist students should have to explain to racist students that they’re racist. It’s racist because the notion that a classroom is some kind of utopic space in which the hierarchies of our culture are somehow escaped enables the hierarches to skid past consideration, and thereby, those hierarchies are enabled by “free” discussion.

But, if you’re teaching a class in which you want to persuade people to think about racism, you have to have a class in which people can express attitudes that might be racist. Open discussion won’t work, and blogs still have a lot of discursive normativity, and so you need a way in which students can be open with you and say things they don’t want to say in front of other students.

And so you have microthemes.

Students feel more free to express views that they wouldn’t say in front of other students, and they’ll tell you if they haven’t done the reading, so I walk into class knowing how many students didn’t do the reading.

There are some disadvantages. You can’t reuse old lecture notes; you can’t prepare a powerpoint. And, since I’m the one presenting views that students have, there is a reduction in student to student conversation (it gets me hits on teaching observations but, since student to student interaction is deeply problematic in terms of power, I’m okay with that).

And, since undergraduate lives are, well, undergraduate lives, students don’t always remember what they’ve said in microthemes. And there is a tendency for students (especially graduate students) to feel that, since they’ve already told me what they think, they don’t need to say it in class.

But, still and all, I wish I’d adopted microthemes years before I did, but with a different name.

My area of expertise is what I’ve taken to calling “train wrecks in public deliberation.” I’m interested in times that communities used rhetoric to talk themselves into disastrous decisions—ranging from the Athenian decision to invade Sicily in 5th century BCE to LBJ’s decision to escalate the Vietnam War in the summer of 1965. I came to notice patterns–not of political personalities or even policies but of cultures of discourse— what I came to call demagoguery.

All political issues are policy issues, and we always have a variety of policy options available to us. In these cultures of demagoguery, that rich and nuanced world of policy options was and is denied in favor of framing our cultural problem as a question of a zero-sum battle between two groups: us and them. When we’re in a culture of demagoguery, when everything is framed as two sides, those two sides appear to be on opposite sides of every issue, but they actually agree about quite a lot.

They both agree that there is no legitimate disagreement with their position; they agree that politics is a zero sum battle between us and them. They just disagree as to who is whom. They agree that for every problem there is one solution and that disagreement is the consequence of the presence of people with bad motives. This agreement that disagreement is useless can come from several different positions, but two are important in our era: political narcissism, and political sociopathy.

For some people there is only one legitimate understanding of the common good (mine) and everyone who disagrees is blinded by self-interest, duped by the media, or knowingly advocating a bad policy. To say that there is only one political good, and that I and only I am the one oriented toward that good on every issue[1] is a kind of political narcissism.

Another position is that there is no legitimate political disagreement because none of us is really interested in the common good—there is no common good at all. We are all our for ourselves, and no position is ethically superior to any other–there are just winners and losers, and any political or rhetorical strategy is allowed if it’s oriented toward winning. This is a kind of political sociopathy.

Those aren’t all of the positions possible, but they’re two that I hear a lot when people are arguing for a no-holds barred wrestling match between us and them. I think the people who advocate those positions are sincere. I think that people who argue that they and only they are advocating the one political good in every situation believe that is true; they cannot imagine that any other position might have any legitimacy in any circumstance. They believe that everyone sees the world exactly as they do.

And those who believe that everyone is out for their own good are out for their own good, and they think everyone else is too.

What neither of those two realize is that not everyone is like them—they universalize from their own position, posture, and ideology.