If you had said to a theologian in the era when Aristotle was considered the authority that, perhaps, the substance v. essence distinction was not useful, you might have found yourself with burning wood at your feet. You certainly would not have been popular. Yet we now think it was a thoroughly useless distinction—meaning we now think they never needed to make it, and that they only did so because they thought it was important to Aristotle, and he was The Authority, and working within that odd binary was what you did.

We now consider the substance/essence binary kind of a joke since it really only made sense within Aristotelian physics, which was wrong.

Scholars and teachers of writing can sit smugly in our chairs and smirk at those dumb people who worked so hard to make things work within what we now see as the false binary of substance v. essence, while we work, write, teach, and assign textbooks that work just as hard to promote the equally false binary of rational v. irrational.

You can tell it’s a false binary by asking someone to define what it means to be “rational.” They will describe five wildly incompatible ways of determining rationality:

1) the emotional state of the person making the argument (whether they seem emotional);

2) which is determined by linguistic cues, such as what linguists call boosters (words like “absolutely,” “never”)—generally whether the tone of the argument seems to the reader more extreme than the argument merits;

3) whether the argument “appeals to” data, “logic” (this is generally bungled);

4) whether what they say is obviously true to reasonable people;

5) whether the argument appeals to expert opinion (or the author is an expert).

These five criteria for determining rationality are, loosely, the person making the argument strikes us as rational kind of person, whether they’re emotional about the issue, whether they have data, whether what they say seems true to the reader, whether there are experts support the claims.

Those are all useless ways of trying to figure out whether an argument usefully contributes to deliberation about any issue.

Granted, those are the characteristics common usage dictionaries identify, although in a different order from mine. Dictionary.com provides this definition of rational:

1. agreeable to reason; reasonable; sensible: a rational plan for economic development.

2. having or exercising reason, sound judgment, or good sense: a calm and rational negotiator.

3. being in or characterized by full possession of one’s reason; sane; lucid: The patient appeared perfectly rational.

4. endowed with the faculty of reason: rational beings.

5. of, relating to, or constituting reasoning powers: the rational faculty.

And every side (there aren’t just two) says that the problem is that our public discourse is irrational, by which they mean the other side is irrational. That’s irrational twice over—they reduce the complicated world to us v. them, which is irrational, and in that irrational argument, they accuse the other side of being irrational, based on a definition that is irrational. We are in a culture of demagoguery because we believe that there is a binary of rational/irrational, and we think that people who are irrational don’t really need to be taken into consideration when we’re arguing about policies. In fact, they shouldn’t be allowed to participate. We believe that democratic deliberation requires that only people on the rational side of the rational/irrational split really count.

The rational/irrational split is not only a false dilemma, but a thoroughly incoherent and profoundly demagogic way to approach any decision. We are in a culture of demagoguery not because they are irrational (from within the that false rational/irrational split) but at least partially because we (all over the political spectrum) accept that false and demagogic binary of rational v. irrational.

Far too often, we assess arguments as rational or not on the basis of whether the person making the argument seems like a rational kind of person, they’re making the argument with an unemotional tone, whether they have evidence, whether what they say seems true to us, and whether the person speaking can cite authorities.

And we don’t always require that last one. We often treat argument from personal experience as rational evidence, especially if it’s our experience.

For instance, since I have the bad habit of reading comment threads (I know, I really should stop), I ran across a comment on a thread about why you should be hesitant to call the police if you have POC neighbors who get on your nerves, and one commenter said something along the lines of, “I’m a 60-year old white woman who has never had any issues with the police.”

I noticed that comment in particular because I’m a 60-year old white woman who has never been badly treated by the police, and I know so many POC who have, and therefore the experience of someone like me is proof that there is disparate treatment of white women and POC. So, I thought her comment would go in that direction. But it didn’t. Instead, she went on to something like, “So, you just have to treat them with respect.”

It’s important to note that she was using her personal experience to discount the personal experiences of POC who report problems with the police. So, her one argument from personal experience—that they treated her well—was, she thought, proof that they treat everyone well. She was treating herself as an expert, on all experiences with the police.

That’s irrational. But it isn’t irrational because she’s an untrustworthy person, she was emotional in the moment, she failed to provide evidence, or what she was saying would come across as obviously untrue to everyone. Her argument would look rational to someone like her, and to someone who thought as she did.

But it’s a really bad argument. Her experience as a white woman doesn’t refute the claim that POC are treated differently by police than are white women.

Her argument is irrational, but not by the dominant way of thinking about what makes a rational argument. The rational/irrational split is just another instance of confirmation bias—if you agree with the argument she’s making, then her argument will seem rational. If you don’t, it won’t.

I agree that democratic deliberation requires that people take on the responsibilities of rational argumentation, but rational argumentation isn’t about false binaries regarding identity, affect, evidence, truth, or expertise. It’s never about feelings v. emotion, so it isn’t about calm or angry, nor is it about data or not.

People teaching argumentation need to run screaming from the rational/irrational split, and from textbooks and teaching methods that reinforce it.

There are scholars who set high standards for rational argumentation, and others who set low standards. I’m on the low standards side: people are engaged in rational argumentation when we

1) can be very specific about the conditions under which we would change our minds—in other words, what we believe is open to falsification;

2) have internally consistent arguments (that is, basically, we have the same major premises for all our arguments);

3) hold the opposition(s) to the same standards in regard to kinds of proof and logic as we hold ourselves. Thus, if cherry-picking from Scripture proves we’re right, then cherry-picking from Scripture proves we’re wrong. If a single argument from personal experience proves we’re right, then a single argument from personal experience proves we’re wrong. Arguments from Scripture or personal experience aren’t necessarily rational or irrational—but how we handle them in an argument is.

This way of thinking about what makes a rational argument means we can’t assess the rationality of an argument without understanding the argumentation of which it is a part.

An argument—a single text—can’t rationally be assessed as rational or not on the basis of just looking at that single text.

Or a single personal experience. If you think about rational argumentation this way, then things like arguments from personal experience are part of the deliberation, and they are datapoints we have to assess just as we would a study. If there is a study that contradicts a lot of other studies, we don’t immediately assume it’s right, nor do we immediately assume it’s wrong. We look at its methodology, relevance, quality relative to the other studies; we look at whether it’s logically relevant to the case at hand.

We treat personal experience the same way. A white 60-yo woman who has always had good experiences with the police is a datapoint. One that shows that white women are treated well by the police. It shows nothing about POC experiences with police.

I think it is useful to characterize arguments as rational or irrational, or, more accurately, to talk about the ways in which they are rational and irrational (since many arguments are both). But, dismissing an argument as irrational simply on the grounds of surface features of a text (the argument is vehement, contradicts what we believe) or purely on in/out-group grounds (the source is irrational because out-group, it contradicts beliefs I think are true), or categorizing the argument as rational because of surface features (it has data, it seems calm, it makes gestures of fairness, it cites experts) or purely on in/out-group grounds (it confirms what I believe, the person seems in-group)–that’s irrational.

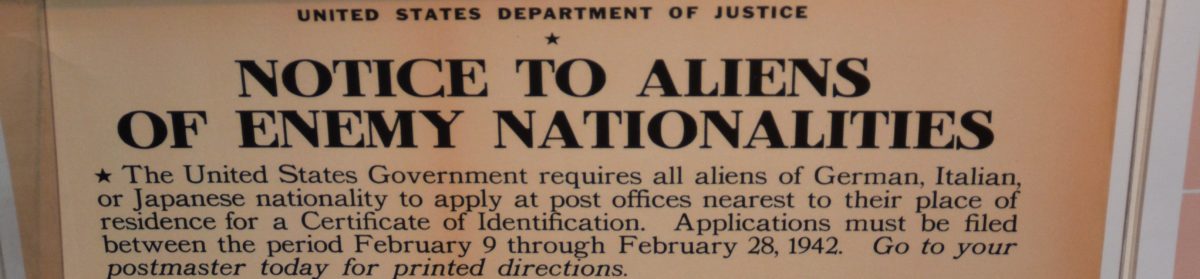

[The image is from Modern Dogma and the Rhetoric of Assent, as this is all thoroughly grounded in Booth’s argument.]