Martin Niemoller was a Lutheran pastor who spent 1938-1945 in concentration camps as the personal prisoner of Adolf Hitler. Yet, Neimoller had once been a vocal supporter of Hitler, who believed that Hitler would best enact the conservative nationalist politics that he and Niemoller shared. Niemoller was a little worried about whether Hitler would support the churches as much as Niemoller wanted–Hitler and the Nazis had exhibited a possibly purely instrumental support for Christianity. But, under the Democratic Socialists, the power of the Lutheran and Catholic churches had been weakened, as the SD believed in a separation of church and state, and Neimoller thought he could outwit Hitler, get the conservative social agenda he wanted, disempower the socialists, and all without harm coming to the church. After the war, Niemoller famously said about his experience:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.[1]

Niemoller was persuaded that Hitler would be a good leader, or, at least, better than the Socialists. After the war, Niemoller was persuaded that his support for Hitler had been a mistake. What persuaded him either time?

A colleague once said that, if Hitler hadn’t existed, rhetoric classes would have had to invent him. Hitler does seem an inevitable topos in arguments about politics. Godwin’s Law states that, as an internet argument goes on, the chances of Hitler being invoked rise, and someone saying “HITLER DID THAT TOO” is notoriously a sign that the disagreement has gotten caught in a nasty back eddy of anger and contempt. Argumentation theorists call it the fallacy of argumentum ad Hiterlerum, when someone tries to discredit a policy, argument, or opponent by accusing them of being just like Hitler.

This isn’t just an odd thing about the internet. The fact that comparing someone to Hitler is a sign of failed argumentation is a really sad thing about how Americans are arguing about politics, since that comparison should be something we make thoughtfully. If everyone is Hitler, then why make the comparison? It’s just a way of saying “I don’t like you.” If every law or order with which we disagree is just what Hitler would do, then we should either always and never be in a panic. Calling someone Hitler is what, in 1984 would be called “double plus ungood.” It is a very vague way to say, “Yuck.” And if every politician is Hitler, then no one really is, or it isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and that’s a weird conclusion—so it’s useful to try to figure out if a politician really is like Hitler.

If we agree that Hitler was disastrous for his country and our world, and I think we should, then we want to understand what happened, we need to understand what enabled him to rise to power, destroy democracy, start the most destructive war of history, drag a country into self-immolation, and deliberately plan serial genocides.

It’s important, therefore, to see if there really is another Hitler goosestepping toward us, and not just fling that accusation at any politician we dislike. If the “You’re just like Hitler” is something everyone throws around, then we can’t think effectively about whether this moment is concerning.

We can agree that various groups (internal and external to Germany) should have taken the threat of Hitler more seriously long before they did, So, the first question of this course is: what would it mean for us to bring up Hitler in a way that usefully advances an argument rather than ends it? How should the example of Hitler function in our rhetoric?

1. Rhetoric

Aristotle defined rhetoric as “the art of finding the available means of persuasion in a given case.” Aristotle’s insight is that we rarely (or never) have available all the possible means of persuading others; we’re constrained by factors such as our audience’s existing beliefs, prior experiences, level of information, degree of conviction, how much credibility we have with that audience, and even such factors as time and technology (rhetorical constraints). For instance, if we have the attention of an audience for a very short amount of time, we have fewer options for persuasion than if we have their attention for a longer period.

Persuasion is a surprisingly complicated concept, much more than people realize. But, for now, let’s define it this way. Persuasion has three parts: the people we’re trying to persuade (our audience); beliefs we want people to have, to act as though they have, or to act upon (what we might call “claims”); second, the strategies available to get people to have those beliefs or behave in those ways.[2] And, as Aristotle pointed out, there are two general ways you can persuade: what is generally translated as “artistic” versus “inartistic” proofs. It’s an unfortunate translation, since what he means is that there are arguments within a rhetor’s control (the arguments s/he makes in speeches) and ones not open to the rhetor’s construction (not constructed by the rhetor, such as pre-existing beliefs, historical events, things other rhetors have said).

So, if we’re going to study Hitler’s rhetoric, we’re going to look at what beliefs/actions he wanted people to adopt, who those people were, and what strategies he used to get that adoption. And we’ll have to think about artistic and inartistic proofs, and what I’ll argue is that Hitler benefitted tremendously by inartistic proofs.

Relatively early, at least by the time of his autohagiography Mein Kampf, Hitler had certain goals from which he didn’t vary.[3] These were:

-

- Aryans/Germans (he was, like most racialists, sloppy and muddled in his racial taxonomies) were entitled to political, economic, military, and cultural dominance of Europe;

- Germany must become purely German (again, a muddled notion never clearly defined), and engage in a kind of intra-continental colonialism, taking over large parts of central and eastern Europe (the amount varied over time), making the current inhabitants essentially serfs of German settlers;

- Germans were victimized by anything that didn’t allow them such dominance (such as other counties resisting the dominance);

- Germany had been about to achieve such dominance in WWI, but was prevented from victory by a “stab in the back” on the part of Jews—who, he said, controlled the media, and caused Germans to give up;

- The historical moment was a battle between fascism and Jewish-Bolshevism;

- Germany could not achieve its divinely-determined end of a master race that dominated Europe as long as there were any Jews in Germany, so Germany (and all the lands it controlled) must become “free” of any Jews (or other genetically tainted groups);

- democracy, with the attendant notions of human rights (including an apolitical judicial system, free speech, freedom of religion) and the benefits of public multi-party debate over policies, was a Jewish plot;

- The New Germany would not have class conflict, although it would still have classes, because it would not have a rigid and snobbish hierarchy in which Aryans looked down on other Aryans—it would instead have a rigid and snobbish hierarchy grounded in race (this is what was meant by “national socialism”—equal opportunity for members of the same race, with all members of that race fully committed to the German nation);

- He was destined by God to lead Germany to its victory over Jewish-Bolshevism and had been given almost supernaturally good judgment (on any topic), stamina, will, and luck;

- Because his end goals were so good, any means that he used to achieve those ends were good. He was, therefore, entitled to lie, embezzle, order murders, attempt a coup, or anything else in order to get himself to a position where he could lead Germany to its destiny, and Germany was, therefore, entitled to exterminate any people, peoples, or nations that might inhibit (let alone stop) Germany’s attaining its goals. Hitler, the Nazis, and Germany were exceptions to the normal rules of ethics and behavior.[4]

Notice that Hitler didn’t have to persuade everyone to believe these claims; he needed to persuade a large number of people to allow him to act on them. And, as will be discussed later, lots of people (especially but not exclusively Germans) believed many or all of these things before Hitler rose to power—he rose to power because so many people believed enough of them. Many people believed in Hitler because they already believed in what he said; despite his reputation, he wasn’t such a rhetorically powerful individual that he, and he alone, magically converted Germans into mindless tools of his will.

In popular thought, Hitler is the gold standard for demagoguery, and it’s common to attribute to him—specifically to his extraordinary rhetorical power–Germany’s descent into serial genocides, a war of extermination, and irrational fanaticism. That isn’t how scholars of the Holocaust or World War II describe what happened, nor why it happened, however. In fact, they point out that Hitler’s popularity varied considerably from 1924-1945, and they argue that his popularity correlates more closely to political events than to his rhetoric.

In the early 20s, numerous people describe being powerfully moved by him, and the crowds getting unhinged with enthusiasm for him. In Munich, the biggest venues available to him weren’t big enough to hold all the people who wanted to see him. Then he tried to overthrow the government violently (despite having promised, on his word of honor, that he wuldn’t), and, when he came out from his very shortened sentence, the German economic situation was better, and he couldn’t fill the houses. His rhetoric was exactly the same as it had been when he was magical, but the magic wasn’t working. And that’s interesting. It means his popularity wasn’t purely a consequence of his rhetoric, but how his rhetoric fit with the historical and economic context.

When the world economy collapsed, the Nazis started doing better in terms of popularity, but they never had the votes for Hitler to take power as dictator (and, as the government was enacting more sensible economic policies, and the economy was improving, the draw of the Nazis was decreasing). For complicated reasons (explained later in the course), conservative political leaders who were completely unwilling to have a coalition government with the Democratic Socialists or Communists, decided that they could play Hitler—allow him in the government, and yet outwit him continually. He insisted on being brought in as Chancellor, and they agreed. After the Reichstag fire, Hitler insisted on dictatorial powers (something many of the conservatives had wanted anyway), but there weren’t enough votes to pass the necessary legislation. The government allowed the Nazis to arrest, threaten, and even kill communists and forbid any of them to vote in the Reichstag. In March of 1933, all the other political parties, except the Democratic Socialists (what we would call “liberals” or “progressives”)–including the Catholic party–voted for “The Enabling Act,” which gave dictatorial powers to Hitler.

They did this although Hitler had wobbly popular support in 1933. In the next two years (1933-34), his popularity increased, and it skyrocketed in 1939, as Hitler led his country into an unnecessary war. Between 1933 and 1939, it wobbled a few more times, but his rhetoric remained more or less consistent (1933 is an outlier); therefore, there isn’t some clean and clear line of causality between what he said in his speeches and articles and his popularity. He wasn’t some kind of all-powerful magical rhetor who waved a word-wand and transformed good people into bad. But his rhetoric mattered in some way; it mattered to the people who heard it at some times. So, the second question at the center of this book is what, if anything, did Hitler’s rhetoric actually do?

Further, scholars argue that the word magician narrative—that Hitler hypnotized the Germans—is not just false, but damagingly so. Immediately after the war, it was common to describe Hitler as a magician who transformed basically good Germans into monsters, and, so, now that he was dead, there was no reason to worry about “normal” Germans. Most of them, it was said, didn’t even know the gas chambers existed, and had nothing to do with it. The “evil genius of rhetoric” narrative, in other words, was useful for very deliberately not thinking about what “normal” Germans had to do with serial genocides, German exceptionalism, rabid militarism, and a war of extermination. But scholarship on the Holocaust made quite clear that genocide wasn’t limited to the gas chambers, that “normal” Germans had willingly supported and engaged in it.

There remains a scholarly debate about the extent to which Hitler changed the beliefs of Germans. Certainly, he and the Nazis changed many behaviors on the part of Germans, but was it primarily coercion? Did he change their fundamental values? Was it just a grinding down of normal behaviors so that people would, as in the case of the 101st Battalion, begin by being horrified by actions they would later find easy? If Germans’ beliefs were changed, it’s fair to say they were persuaded—but what persuaded them? A world of violence and coercion? Pervasive propaganda? Nazi successes? An improvement in the German economy? And which of those things should we call “rhetoric”? That’s the third question of this course—how do we describe the changes in belief?

Many observers reported feeling moved by Hitler’s rhetoric, and decided to join with him, some even choosing to die with him. If we decide that his rhetoric did help persuade people to support him, then we have the interesting question of whether he was “good” at rhetoric. That’s obviously a tremendous important question for thinking about how and what we teach in courses on writing, argumentation, persuasion, and communication. Was Hitler’s rhetoric unethical only because it was in service of unethical policies? If so, then teaching his methods to students would be morally neutral. This is sometimes called the “compliance-gaining” model of rhetoric—the goal of every interaction is to get the other person (or people) to comply with what you want; anything you do to gain that compliance is morally neutral. What makes your strategies good or bad is whether what you’re trying to get them to do is morally good or bad.

If, however (and I think this is the case), Hitler’s rhetorical strategies were essentially damaging to his community—if they ensured that people made decisions badly; if that kind of rhetoric is likely to end badly—then we should be teaching students to avoid and suspect any rhetoric that relies on those strategies. Rhetoric, in this view, isn’t a morally neutral set of moves, but itself has a moral valence.

Those, then, are the four questions this course will pursue:

-

- if Germans were persuaded to do or believe things they wouldn’t previously have done or believed, what caused those changes?

- what did Hitler’s rhetoric actually do?

- is rhetoric morally neutral and ethical or unethical only on the basis of the rhetor’s goals? In rhetoric, do the ends justify the means?

- finally when, rhetorically, is the comparison to Hitler a useful and productive move in an argument?

2. How does persuasion work?

To ask whether Hitler was persuasive, we have to decide what we think persuasion is and how it happens, and one of the reasons we end up in unproductive arguments about Hitler and rhetoric is that the dominant model of how persuasion works is not very useful.

The conventional model for persuasion is that a speaker or writer (rhetor) has an audience who believes one thing, and the rhetor wants them to believe something else. You think that little dogs are not involved in the squirrel conspiracy, and I think they are, and so I will try to give a speech or write an argument (or make a movie or whatever—I will create a text) that will get you to comply to my point of view. I want you, by the end of my text, to have entirely rejected your beliefs about little dogs in favor of the one I have. If I present you with an effective text (speech, article, tweet, link), then, after hearing or reading my text, you will change to believing little dogs are part of the squirrel conspiracy.

By this model (which I think is silly), an effective text is one that causes that change of belief in the audience. This is called the “compliance-gaining” model (and there will be more about this later). If the audience’s belief does not change in the way the rhetor wanted, then, according to this model, she did not create an effective (i.e., persuasive) text. Every once in a while, someone does a study in which people who believe one thing are given evidence that their belief is wrong, and, sakes alive!, the people don’t immediately and completely change their minds! The study concludes (and clickbait articles announce) that this study proves that no one ever changes their mind, or that you shouldn’t even try to argue politics, or that no one changes their mind due to rational arguments (if the test text had statistics). But that isn’t what those sorts of studies show at all. What they show is that the compliance-gaining model is nonsense. Still, it’s the one most people have.[5]

Understanding what Hitler and the Nazis did means understanding that persuasion is very, very rarely a rhetor telling a hostile audience that they are wrong and giving them information that causes them to adopt new beliefs. The most effective persuasion makes you think you’ve always already believed this argument because it fits so sweetly with things you already believe (this is an instance of enthymematic reasoning). The most powerful rhetoric fits so neatly with your situation, and your need to manage cognitive dissonance, that it doesn’t look like rhetoric. The most powerful rhetoric, in that sense, is probably not the best rhetoric for a community, but that’s something discussed toward the end.

These studies show that giving people a single text with acontextual new data doesn’t change their minds on important issues: those studies don’t show that data is ineffective, nor that people never change their minds. What they show is that people are resistant to change our beliefs, and that’s probably true, and probably good. In its own way, it’s rational. We don’t change our minds about a belief we value on the basis of one counter-argument presented in a psych lab because we really shouldn’t under those circumstances. And that makes sense, since otherwise people would be flopping from one belief to another. We do change our minds, but how quickly and easily we do so depends on what the belief is, how important it is to us, what beliefs it’s connected to, who is trying to get us to change our minds, and what kinds of arguments they’re making.

The more that a belief is connected to our sense of identity, especially our sense that we are, on the whole, a good person (and that people like us are, at base, good people—that is, the more we are prone to the cognitive bias of in-group favoritism), the more resistant we will be to give it up, or to admit it is untrue (or even true but harmful). For instance, people for whom religion is important do change religions, but the change is rarely “monocausal” (that is, with only one cause). There might be a single text or experience that is the catalyst for the biggest moment of change (Augustine hearing the child say, “Pick up and read,” for instance), but that moment of change is dependent on lots of other moments, events, beliefs, experiences, texts. People change their political parties, careers, friends, lovers—we do change our actions, behaviors, and beliefs.

But, before I can explain that, there has to be a digression as to what we mean by “beliefs” comes up, and it’s a surprisingly complicated question. We have a lot of beliefs, and many of them conflict with one another, and we’re not even aware of all of them. For instance, I’ve noticed that some people refer to any cat they don’t know as a “she,” and any dog they don’t know as “he.” That behavior indicates an implicit belief that cats are more likely to be female and dogs more likely to be male (or that cats are somehow feminine and dogs masculine), but if I ask them if they think cats are likely to female, they’ll say, “Of course not.” That isn’t an explicit belief of theirs. Their explicit belief is that dogs and cats have comparable distributions of male/female, and it’s in conflict with the belief implied by how they refer to dogs and cats. I might believe superstitions are silly, and yet go to some trouble to avoid walking under ladders—my implicit and explicit beliefs don’t match.

This distinction between explicit and implicit beliefs is important, in that people have a tendency to assume that the motives and beliefs of others are transparent to us (this is a famous cognitive bias, and called “the fundamental attribution bias”), and that we can see into the souls of others. We’re also likely to assume that statements of belief are accurate—if someone says, “I believe that squirrels are evil,” we will think that’s what they believe (this is the process that Hitler used to gain legitimacy and normalcy). Hitler had, for years, expressed exterminationist, expansionist, and authoritarian beliefs, and had acted as though he sincerely believed those things, but, when he suddenly claimed to have entirely different beliefs, he persuaded people that his previous rhetoric was insincere and his current rhetoric was sincere. German voters faced the contradiction of a rhetor who had clearly said he did and didn’t believe that expelling Jews from Germany was necessary, that Germany should go to war as soon as possible, and that the war would be with the countries to the East. His rhetoric persuaded people to ignore his rhetoric. That’s an interesting contradiction (more on that later).

There are lots of contradictions in our beliefs.

Milton Mayer went to Germany after the war and spent a lot of time talking to ten different men who had supported Nazism. He mentions that one of them, the second time they talked, defended Nazi treatment of Jews saying “they ruined my ancestors for generations back. Stole everything from them, ruined them” (139). In a later conversation, Mayer says, this same person said, that up until the present, his family had never had any great troubles, never lost land or homes. So, he believed that every previous generation had been ruined and no previous generation had been ruined. Had Mayer pointed out the contradiction to his friend, it’s interesting to think what would have happened. That friend justified the Nazis’ treatment of the Jews, even after the war, on the grounds of antisemitic rhetoric. His beliefs were in contradiction.

What I want to argue is that one of the most powerful impacts that public rhetoric has is to enable people to manage those contradictions in our beliefs. After all, we often believe incompatible things, and there are moments that the contradiction is made present. That moment of contradiction is potentially a moment of growth, but it can also be a moment of retrenchment. Public rhetoric—the arguments and assertions we’re hearing around us—help us move toward growth or[6] insulation in the sense that you are shoring up other beliefs—protecting them from contradiction. Nazi rhetoric was so effective because it ensured that people only heard arguments and assertions that would facilitate insulation.

Melita Maschmann was a Hitler Youth who was active in kicking Poles off of their farms so that “good Aryan families” could take them over, and, at one point, this meant not just her personally throwing them out of their farms, but making sure those people took nothing of theirs that Nazis might value. She was robbing people. And her description of just how she managed to rob families without feeling sympathy is horrible and yet plausible. What she says about herself and the other young girls (your age or younger) who were kicking people out of their homes, stealing their belongings, and sending them to a vague fate was “There is no doubt that we all felt we stood there in the name of ‘Germany’s mission’ and that this mission afforded us safety to act and a mysterious protection” (149). She believed that the ends (“Germany’s mission”) legitimated the horror she was personally inflicting on people (the means). She was a Machiavellian.

She describes sometimes asking the SS officers where the Poles being thrown off of family farms, and they were given vague answers about their being moved to empty farms in the “General Government” area that didn’t entirely make sense, and she knew they didn’t make sense, even at the time. But, she says,

“These answers satisfied us. I have already told you how good we were at giving awkward questions a wide berth. Our subconscious generally took very good care to see that we never became involved in dangerous discussion at conscious level in the first place. Even if we had pressed on to the realization that there could not possibly be enough farms standing empty in the General Government for all those who had been expelled and that many of them would be abandoned to homelessness and the direst poverty, this discovery would still not have worried us. The Poles were our enemies. We must exploit the moment when we’re stronger than them, to weaken, their ‘national substance.’ Such arguments were called ‘political realism.’ I never admitted to the fact that we were basically planning to commit genocide.” (152)

Maschmann didn’t have the explicit belief that she helping exterminate these people, but she had beliefs that legitimated and caused exactly the actions that logically necessitated the exterminations of those peoples.

And Maschmann’s description is an epitome of what went wrong in Nazi Germany, and it echoes what Niemoller said. And there are four important points about how normal people came to engage in (or justify) appalling actions that thoroughly violated their supposed ethics:

-

- they decided it was okay to violate their basic ethical system (“do unto others” “ the law should apply equally to all people regardless of the judge’s feelings” “don’t take pleasure in the pain of others”) because it was a situation of us v. them extermination—either the in-group would be exterminated, or we would exterminate all out-groups;

- they were just trying to survive, stay out of the view of the Gestapo, be thankful for better basic conditions, and not do anything that would get them intro trouble;

- that strategy of trying not to get in wrong with the Gestapo necessarily meant they would one day find ourselves being cruel to a Jew, leftist, Pole, or some other enemy of the Reich. At that moment, and we all have those moments, a person is faced with admitting that we are coerced into violating our ethics; we can choose punishment for doing the right thing; or we can do the wrong thing and try to persuade ourselves it was actually the right thing. And here rhetoric is crucial. Once we have been cruel, we have to find a way to resolve the cognitive dissonance of our sense of ourselves as good and kind people, and the bad and unkind thing we’ve done, and we have two choices: to admit that we are capable of behaving very badly, or rationalize our bad behavior. That rationalization enables other rationalizations. Choosing not to say hello to a Jew creates the cognitive dissonance of being a nice person and have done a shitty thing, and, unless we’re willing to admit it was a shitty thing (which might get us into trouble with the second point—with the Gestapo), we’re going to find a way to rationalize how badly we treated the Jew. So, our shitty treatment of that one Jew in that one circumstance might make us more likely to find antisemitic rhetoric persuasive.

- The just world model (aka, just world hypothesis) says that people get what they deserve. Sadly, rather than being a model that makes us try to act in order to ensure that people get the good things they are currently denied (in- and out-group), this model encourages us to believe that people suffering have done something to bring it on. Maschmann describes the impoverished and hopeless state of the Poles whose property she is helping to steal and whom she is helping to displace as a reason they are less deserving of that property (ignoring that the Soviets had already passed through the area). She mentions that at the same time she thought ill-kept farms and homes were proof of the unfit nature of the Poles she didn’t draw the same conclusion about Germans with ill-kept homes and farms (she only realized that contradiction after the war).

We tend to justify our bad treatment of the out-group by attributing different motives to them, so that they deserve bad treatment—even if they are behaving in ways we rationalize on the part of the in-group (such as the ill-kept farms). We can explain behavior through internal (motives) or external (context) factors.

|

In-group |

Out-group |

| Good behavior |

Good motives |

Bad motives or external factors |

| Bad behavior |

External factors |

Bad motives |

Thus, Germans (her in-group) shouldn’t be judged by their bad behavior (unkempt farms) but Poles (her out-group) shoud

In addition, the rhetoric about the “General Government”—even though it was implausible–enabled her to keep herself from thinking about the necessary consequences of her actions. To do her job, she couldn’t think about what she was doing; she just had to believe that she was right. She substituted belief for thinking. And she was able to do that because her model of how to reason was Machiavellian—the ends justify the means. So, Maschmann’s in the moment thoughts (what she thought—her cognitive processes) seemed to be justified to her because they fit within a way of thinking about how to think (her metacognition). If, instead of thinking “the ends justify the means,” she believed, “do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” she couldn’t have done what she did, or believed what she did.

Ethics isn’t about what you believe; it’s about how you believe. It’s about how you assess whether your way of thinking is a good way to think.

Macschmann describes moments of being aware that she was violating her ethics, that she was tamping down empathy, but she pulled on things she’d been told by propaganda (rhetoric) to enable her to feel better about the obvious ethical contradictions in her behavior. When we’re in the mode of insulation—of trying not to think about what we’re doing–, we persuade ourselves (generally with help from public rhetoric) that the contradiction is manageable, and doesn’t require we seriously reconsider our commitments or sources of information. Rhetoric often serves to make us feel comfortable with beliefs we already have.

Some social psychologists describe a pyramid of harm. Imagine that you do one pretty awful act to someone else, that violates your ethics. You now have a lot of cognitive dissonance between your sense of your self as a good person who does good things, and this shitty thing you have done.

To take a less fraught example, I might believe that Hubert is a completely evil political figure, and that all Hubertians are fools at best and corrupt at worst, and I am especially worked up about Hubert’s having been shown to be friendly to little dogs. For me, this is an irrefutable datapoint for why any sensible person would reject Hubert. It also makes me angry. Just thinking about the photos I’ve seen of him with little dogs makes my blood pressure jump; I believe that his cavorting with little dogs shows the complete moral bankruptcy of him and everyone who supports him. I believe there is no excuse for what Hubert has done because playing with little dogs is unforgiveably bad. Then imagine that I am shown a picture of my favorite candidate, Chester, cavorting with a little dog. I’m faced with conflicting beliefs:

-

- I believe candidates who play with little dogs are evil;

- I believe Hubert is evil;

- I believe Hubert supporters are idiots for supporting someone who plays with little dogs;

- I believe Chester is good;

- I am looking at evidence that Chester played with little dogs.

These beliefs create cognitive dissonance, and I have various ways I can reconcile them. Basically, I can reject and/or modify any of those five. I might decide that I was entirely wrong to condemn Hubert for playing with little dogs, thereby also changing my opinion about Hubert supporters (this is the least likely, for reasons explained later). I might decide that Chester is not good; I might decide that the evidence is fake; I might decide that there are exceptions to playing with little dogs, and it really has to do with someone’s motives in playing with them; I might decide it wasn’t really playing.

Which of those I choose will depend on whether any of those beliefs is attached to my sense of identity (as a good person, a good or bad judge of political figures, committed to hating little dogs, being better than Hubertians), how often I’ve taken those stands in public, whether my commitment to one of those stands has caused harm (oddly enough, if I’ve caused harm to others through my commitment to a belief, I’m less likely to abandon it without a fight), and the relative ranking of their importance to me.

The more that I identify with Chester—that I believe he is the same sort of person I am, that he really understands me, that he represents me—the more committed I will be to protecting my beliefs about him from disproof. If my commitment to Chesterianism is what scholars of rhetoric call “identification through antithesis” (or “unification via a common enemy”) then my commitment to Chesterianism is dependent on our group (the in-group) being as good as the other group (Hubertians, the out-group) is bad. Chester and Hubert engaging in the same behavior is really threatening to my sense of my group being absolutely good. We get pleasure from feeling better than the out-group, and so, the more that my in-group identity (Chesterians) is dependent on our being better than the out-group (Hubertians)—the more I engage in zero-sum thinking about groups, the more I will feel personally attacked and very threatened by anyone who points out that Chester played with little dogs. Under those circumstances, I will declare that the photo is faked, the photo comes from a bad source (I’ll called them “biased”), the people who make this argument have bad motives, and so I don’t even have to engage with their argument that Chester played with little dogs (that’s called motivism).

If my sense of self-worth is entangled with my belief that Chester is good (charismatic leadership, explained later), then I will defend Chester just as much as I would defend myself. If my commitment to hating little dogs is just as strong as my sense that Chester’s success or failure are mine (that I identify with Chester), then this photo presents me with very loud and insistent cognitive dissonance.

If it’s important to me to believe that Chesterians are inherently better than Hubertians, and that Chester is good, and that I have good judgment about politicians, my most likely response is to make distinctions on the basis of motive. And there are two ways I will flick away the clear evidence of my beliefs being in conflict. First, I will make all sorts of distinctions—this might look like playing, but it’s really training, or chastisting, or self-defense (that move is dissociation). Or, I might attribute different motives to Hubert’s playing with dogs from Chester’s doing exactly the same thing. Hubert is playing with them because he’s evil, but Chester is “playing” with them in the sense of playing a fish. This move is a combination of the fundamental attribution error (that you believe you can see the motives of everyone else, so you know the motives of Chesterians v. Hubertians), in-group favoritism (you attribute good motives to your in-group, Chesterians, and bad motives to any out-group for exactly the same behavior) and motivism (you don’t need to listen to the arguments of people you have decided have bad motives).

If your sense of your self is strongly connected to Chester being always good, then you can use those moves to kick the disconfirming evidence to the curb. If I don’t have that kind of commitment to Chesterianism, then I don’t feel personally attacked by someone showing the photo, and I can think reasonably about what the photo means. If my belief about little dogs is much stronger than my commitment to Chester, then I might find it easy to change my mind about supporting Chester.

The more that I identify with Chester—I think he gets me and I really know what he’s thinking—the less I am likely to try to argue his policy proposals through the stock policy issues (explained below). There is an interesting kind of circle here. A lot of people believe that the world is divided into binaries—you’re either good or bad, right or wrong, certain or clueless, with us or against us. Those people think in binary paired terms (what Perelman called philosophical paired terms). So, for people who think that way—in binary paired terms—the central pair is in-group v. out-group. Therefore, if you can find any way that a person presenting an argument that makes you uncomfortable is connected to one of the bad terms in your sets of binary paired terms, you can just not consider what they’re saying.

Binary paired terms is probably the concept in my classes with which students struggle most, and yet it’s the one a lot of students identify as the most useful. Basically, it’s how you get suckered.

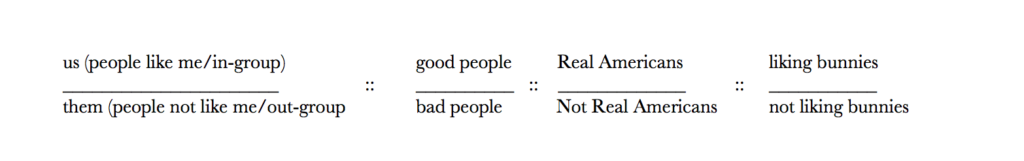

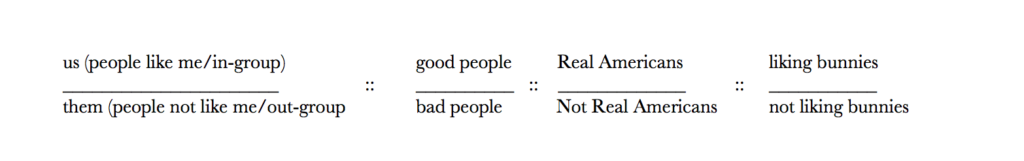

If you value bunnies, and your culture persuades you that valuing bunnies is necessarily connected to being a true American, and you’re prone to thinking in binary paired terms, then you’re likely to conclude that someone who doesn’t value bunnies is a bad American.

Here’s how you reason. A person either values bunnies, or they don’t. A person is either a good American, or a bad American. It’s paired terms.Like a lot of logical fallacies, it’s preying on a way of reasoning that can be logical.

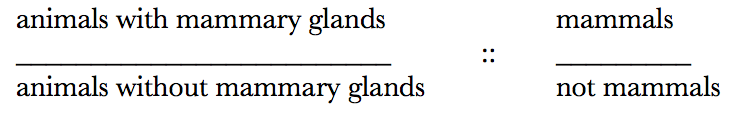

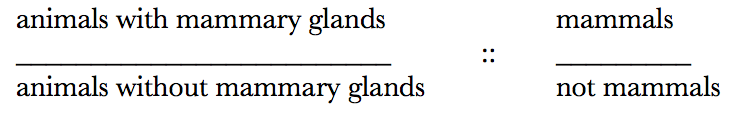

Imagine this way of reasoning:

Notice that mammals and mammary glands do have a necessary logical connection (that’s the definition of mammal). But “real Americans” and “liking bunnies” aren’t necessarily connected; it’s an arguable connection. So, If someone wanted to assume that liking bunnies and being American are necessarily connected, she’d need to be willing to argue the connection, with citations, reasons, and examples. When we’re reasoning from paired terms, however, we just get angry when someone contradicts our association.

If we aren’t willing to argue (and not just assert) the connection, then this isn’t logical reasoning at all, but reasoning by association. You assume that all Real Americans like bunnies, so, if someone says they don’t like bunnies, you accuse them of not being a real American. Or, “us” is to “them” as “liking bunnies” is to “not liking bunnies.”[7]

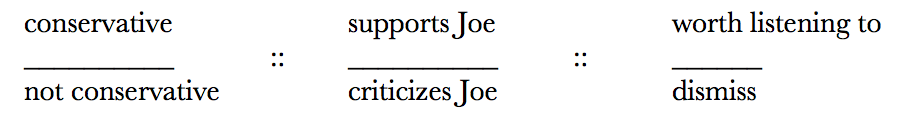

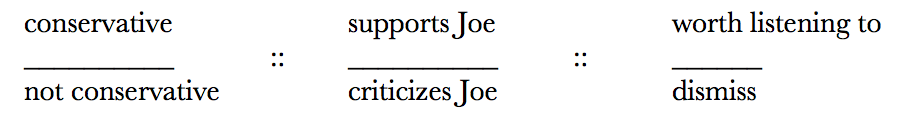

All of this is implicit. We don’t always know when we’re reasoning from binary paired terms. For instance, I was recently arguing with someone (call her Jane) who wanted to claim that a President (let’s call him Joe) was doing really well in regard to another country, and I pointed out that the consensus among people observing the situation, from every political perspective, including conservative, was that Joe was not doing well. Jane admittedly could not come up with any source to support her position, so, she argued that every source of mine was wrong because it was not conservative because it did not support Joe. Jane’s set of binary paired terms was this:

So, what you have to notice is that Jane had protected her beliefs from any disconfirming evidence. Jane can’t be proven wrong because her beliefs derive from her commitment to Joe—she can dismiss anything (usually as “biased”) that might challenge her beliefs about Joe. What’s important about this is that, if Joe does have flaws, Jane can’t hear them, and, therefore, Jane can’t learn—she can’t learn about Joe, or about Joe’s policies, or even about her own way of reasoning. The more that Jane supports Joe in public, the harder it will be for Jane to admit the error in supporting Joe, and the more that Jane can find herself supporting positions she would previously have rejected.

Jane’s political agenda has ceased being a coherent political agenda (although she can always find assertions to support her Joe-generated political agenda), and it has become rabid factionalism.

As long as she is irrationally committed to getting information only from pro-Joe sources, Joe can get her to commit to policies she would have previously rejected, and keep her within his echo chamber because Jane has become convinced that political deliberation isn’t about listening to various points of view, checking data and sources, but is entirely about rabid factionalism. If Jane believes that good policies come from policies advocated by her in-group, then all she needs to know is that her in-group media says this is a good policy, and she will dutifully repeat the talking points her media has told her to say.

Here’s what Jane can’t do. (And here’s how to know if you’re Jane.) Jane can cite a lot of data (since her sources have told her talking points that include data), but she can’t cite sources. If really pushed, some Janes can get pressured into citing sources, but they can’t cite sources outside of their in-group. If you can’t cite sources, or you can’t cite sources outside of your in-group, then you are repeating propaganda.

Jane doesn’t hold the in- and out-group to the same standards. Jane can think she is, because she is well trained in whataboutism. Her media tell her what the out-group thinks, so she thinks she’s informed on both sides (inoculation), and she thinks she’s being fair because she’s pointing out that the “other side” is bad.

For Jane, then, issues about policies aren’t determined or debated on the basis of what the policies will or won’t do, but as though the important question (the only question) for every political issue is which group is better. First, you divide all political positions into in-group (narrowly defined) and out-group (everyone else). Second, you use any behavior on the part of any out-group member to smear all the various groups you’ve included in the out-group. Third, you refuse to listen to any descriptions of bad behavior on the part of in-group (since your pro-Joe media doesn’t mention them, unless it’s part of “Those people are nuts because they say this,” and they promptly give you a talking point for refusing to think about that criticism). So, once Jane has committed to Joe this way (it’s called charismatic leadership) she can think in zero-sum terms—as long as she can think of a way the out-group (aka, anyone who disagrees with her, or gives her information she doesn’t like) is bad, she can feel good about being better.

Pointing out that people are condemning behavior in the out-group that they defend in the in-group can be good, and useful, if it’s part of an argument that we should hold all groups to the same standards, and the failure to treat all parties the same can be a sign that someone’s position is irrational. But, if we’re going to make the “why are you condemning this behavior and not that” in good faith, then you’re inviting an argument about the relative importance of the various behaviors, actors, consequences. If it’s a move toward exploring those issues, it’s interesting.

Usually, however, it’s an attempt to clear the in-group of all bad behavior, so that one (perhaps apocryphal) instance of “bad” behavior on the part of the out-group clears the in-group of any accusations of that sort of behavior. So, for instance, pro-slavery rhetors would invoke that some abolitionists had appeared to advocate violence in order to wipe off the slate the persistent and omnipresent violence of slavery. In this class, you’ll see the Nazis engage in the same rhetoric—their extermination of Jews was justified as self-defense, they said, because some people they said were Jewish (they weren’t always) had killed a Nazi.

As you’ll also see, many Germans felt that their actions against Jews, Sintis, Romas, Poles, homosexuals, socialists, and so on were expiated because they had been bombed—in the course of the war they started. That’s whataboutism at its worst.

Whataboutism is a “get out of criticism free” card, that flattens the actions of various groups (any bad behavior on the part of the out-group neutralizes all bad behavior on the part of the in-group). It also shifts the stasis. In policy argumentation, the stasis should be about what policy is best for the community as a whole. Identity politics makes the stasis which group is better (and authoritarians are all about identity politics). Whataboutism is an attempt to shift the stasis from what the in-group accused has done to what some (any) member of the out-group has done. And, ultimately, it rarely matters.

If I say that Chester lied, then someone saying that Hubert lied doesn’t make what Chester said true. Chester is still a liar. Whataboutism is all about distracting Chesterians from that fact.

Jane won’t see it that way; Jane doesn’t think there is an issue with her refusing to look at anything that might disagree with her, because she believes that the only proof that she needs that her beliefs are true is that she has those beliefs. The more that Jane consumes pro-Joe media, the more that media says that her sense of herself as a good conservative is connected to Joe, the more that she is a naïve realist (that she believes that, if she believes something, it must be true, and that her belief that something is true is all the evidence that is needed)[8], the less able Jane is to argue her position rationally, and the more likely she is to dismiss disconfirming evidence on the grounds that it’s disconfirming.

Here’s how that argument works: instead of assessing the validity of an argument on the basis of how it’s argued (methods that apply across groups), an argument is assessed purely on the basis of whether it is loyal or disloyal to the in-group.

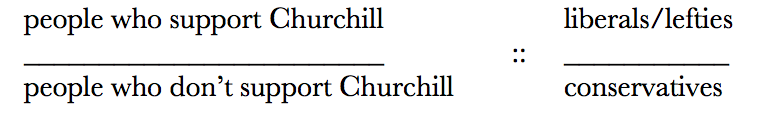

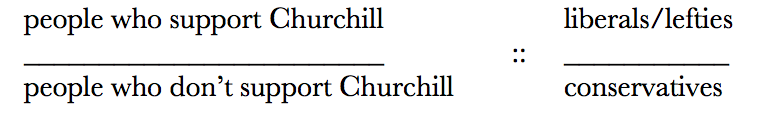

For instance, Ward Churchill characterized people killed in the World Trade Center as “little Eichmanns” and got a lot of grief about it. A self-described lefty relative of one of the people killed in that attack condemned Churchill, and I found myself in an argument with someone (call him Floyd) who insisted the relative, despite what he said, couldn’t really be lefty; he must be conservative. Here was Floyd’s argument:

Jane and Floyd’s arguments were equally irrational, in the sense that neither could

-

- make an argument that applied principles of reasoning across in- and out-group

- identify the conditions of falsification (what would make them admit they were wrong)

- make an internally consistent argument for their position.

Instead, both were reasoning deductively (and in a circular way) from and about group loyalty. Both were using their thinking in ways that justified their sense of their in-group. And neither could admit significant criticism of their way of thinking, so that both could (and can) go through life cheerfully finding confirmations of their beliefs and yet never reconsidering their beliefs. They are both profoundly irrational people who think they have reasons.

When you think of political participation as nothing more than supporting—in any way you can—people who you think embody your values, then you’re a sucker.

So, let’s think about what it would mean to involve yourself in politics in a way that didn’t mean rabid identification with a political figure or party. Let’s go back to the example of Chester being photographed with little dogs. If I am not particularly identified with Chester—if, for instance, I’m more concerned about policies than in-group identification—then I probably never rely exclusive on in-group media for information, and I certainly wouldn’t in this instance.

But, the more that in-group loyalty is important to me, the more likely I am to rely exclusively on in-group media, and I’d turn to in-group media in order to understand how to resolve the cognitive dissonance. That’s what both Jane and Floyd did (and do). And the more they are likely to spend their lives entangled in the inability to argue reasonably for the policies they support.

One of the functions of much public rhetoric is to give members of our group (religion, political party, discipline, team) talking points that will enable them to reconcile cognitive dissonance created by our beliefs being in conflict. The most obvious strategy would be to deny the accuracy of the photo. Chester TV would have pundits claiming it’s faked, the source of the photo is untrustworthy, it’s all a Hubertian plot. This is a kind of persuasion, and much rhetoric, I’ll argue, functions in exactly this way: to reconcile cognitive dissonance in such a way that previous beliefs are protected, confirmed, and possibly strengthened. This is effective rhetoric, not in that it changed a fanatical Chesterian’s belief about Chester, Hubert, or Hubertians to opposite beliefs—it doesn’t give someone new beliefs, as much as renewed commitment to pre-existing ones. A fanatical Chesterian wouldn’t have changed their mind about Chester or little dogs, but would have found a persuasive way not to change their mind about either. That’s the goal of such rhetoric. It’s in-group confirmation.

Chester TV might also have pundits saying that it wasn’t really a little dog, but a puppy, or Chester did it just in a clever political ploy, or had different motives from Hubert so it wasn’t really a bad thing to do. Chester TV might make the argument that Chester’s playing with a little dog doesn’t mean the same thing it does for Hubert—for Hubert, it’s proof that he and his followers are evil, but for Chester, it doesn’t mean that.[9]

Notice that this rhetorical relationship doesn’t quite fit the compliance-gaining model mentioned above. There isn’t a rhetor trying to get someone else to change views; there is rhetoric offered to someone who might use it to make themselves feel better about a belief they already have (or do something they intended to do anyway). The most important kind of persuasion is self-persuasion.

We want to think of ourselves as good people, and so express views that are what a good person would say, but do we really believe them? For instance, in 1942, Earl Warren, then Attorney General of California, testified before a Congressional Committee that “the Japanese” (he actually used a racist term) couldn’t be near the coast, power plants, water supplies, factories, military installations, farms, or forests. That’s an argument for putting them in prison. But, when asked if he was advocating imprisoning them, he said he wasn’t advocating any particular policy. But he was—the entire logic of his argument made imprisonment the only possible solution. I’m sure he really believed when he said he didn’t have a specific policy in mind, but I also think it’s possible that he just didn’t want to acknowledge to himself what he did believe. He just didn’t let himself think about the logical consequences of what he was saying.

There is another famous case, from Nazi Germany. Adolf Eichmann was in charge of various aspects of the Holocaust, especially transportation. When he was brought to Israel to stand trial for his central role in the concentration camps, the police officer in charge of interrogating him asked him about his role in the murder of Jews. Eichmann insisted, that although he was making sure that Jews were put on trains that went to death camps where they would almost certainly be killed, he was not responsible for their deaths, since he didn’t actually kill them. He was engaging in an activity that would result in deaths, but he didn’t believe he was responsible because he was one step away from those deaths, and he could keep himself from thinking about them. He wasn’t antisemitic, he insisted, and didn’t intend to kill Jews, although he did intend and carefully plan, and ensure that Jews were sent to places where they would be killed.

There are two parts to this way of separating our beliefs about our actions from what a logical analysis of those actions would produce: 1) as in the case of Warren and Eichmann, don’t think about the inevitable and logical consequences of the action you are doing (or advocating); 2) since you didn’t think about those consequences, you can tell yourself you didn’t intend for those consequences to happen (you, therefore, don’t have bad motives). And rhetoric can help you feel better about your participation in such acts by enabling you to dissociate killing from real killing. Eichmann wasn’t helping to kill Jews; he was just helping to ship them. He could dissociate real from apparent killing.[10]

It’s interesting to note that Eichmann claims to have vomited when he saw a camp—the kind of place he was sending people–, Heinrich Himmler almost fainted when he saw the kind of deaths he was ordering, and Earl Warren recanted his stance on mass imprisonment of Japanese-Americans when he imagined children going to a camp. They could believe that what they were doing or advocating was okay until they were faced with clear images of the consequences—till they couldn’t not think about it.

Eichmann and Himmler went back to enabling the very thing that appalled them, of course, without seeing any problem. So, how should we characterize their “beliefs” about genocide?

Beliefs are stories we tell ourselves about us, our kind, our world, and others. It is possible to feel great conviction about any belief at a particular moment, and equally great conviction about a completely incompatible belief at the next moment. Sometimes that’s just effective lying (liars always persuade themselves first), and sometimes it’s just the sense that we don’t need to have principles that operate across beliefs. We don’t need to think about whether our beliefs are consistent with each other.

There are four ways of trying to figure out if one of your beliefs is true:

- Ask yourself if it fits with other beliefs that are important to you;

- Ask yourself if you can think of an example, an authority, or find any research to say it’s true (you might even google to see if you can find a supporting source);

- Ask yourself if it conflicts with other beliefs you have that are important to you;

- Ask yourself if you can find an example, an authority, or find any research to say it’s false (that is, try to articulate the conditions under which you would admit it’s a false belief).

Eichmann, Himmler, and Warren could all determine their beliefs were true by relying on the first two—they could find support for their notion that exterminating or imprisoning others on the basis of race fit with beliefs; they all had evidence that it conflicted with other beliefs. Warren, unlike Eichmann or Himmler, paid attention to the third. His horror at the thought of children being taken to camps was a belief that contradicted his belief that “the Japs” as he called them in his testimony, weren’t deserving of the same treatment he would want for him and people like him

Feelings are beliefs that need to be considered. Eichmann and Himmler considered their feelings about Jews, but not their feelings about camps. Warren did both. And so, although his role in the racist imprisonment of Japanese in the US is indefensible, he went on to be a powerful critic of race-based law. Neither Eichmann nor Himmler went on to any deeper understanding of anything. They went to deeper commitments to beliefs they found appalling if they really thought about them.

In other words, they were persuaded to act on some beliefs and not others because they were persuaded not to think about some things. So, one of the very important things that rhetoric can do is to persuade someone not to think, and that’s usually done through dissociation.

Sometimes rhetoric does get people to adopt new beliefs, and, when that happens, it’s typically done through enthymematic reasoning or repetition. Persuasion is limited by our previous beliefs—a rhetor can only move us so far.[11]

Enthymemes are compressed syllogisms, and there’s good research to suggest that we have a tendency to reason by syllogisms (although we probably shouldn’t). Humans tend to think in terms of categories, and to reason either inductively (from specific to general) or deductively (from general to specific). So, for instance, if the only three Canadians you have ever met love rap music, you’re likely to assume that Canadians like rap music (you’re likely to move from the specific cases of those three Canadians to a generalization about Canadians—that’s the inductive reasoning). Once you meet a fourth Canadian, you’re like to reason deductively, and assume she likes rap music.

The syllogistic form of that last argument would be: All Canadians like rap; she is Canadian; therefore, she likes rap.

But, we don’t generally put the first claim (the major premise) into our text—we just assume it (and we assume our audience agrees with it). So, if you and I were talking about having a free ticket to see a rap festival, you wouldn’t say to me, “Let’s invite Ella. All Canadians like rap; Ella is Canadian; therefore, she likes rap and would enjoy going with us.” That would be the syllogistic version. You’d use an enthymematic one. You’d say something like, “Let’s invite Ella; she’s Canadian.” You’d leave it to you to supply the missing connection—that all Canadians like rap. If I didn’t share that major premise—if I didn’t have the stereotype that Canadians like rap—I’d be confused. And, in fact, that’s what makes a lot of conversations confusing—that the people in the conversation don’t share the major premise(s).

In a good conversation, if I didn’t share your major premise, I’d say, “What does her being Canadian have to do with it?” and you’d explain. And then we might have a conversation about whether your major premise is right. In good conversations, people often end up having to talk about the not-shared major premises. In bad conversations, you’d just get mad at me for not understanding your argument. If I said, “I don’t think all Canadians like rap,” you’d need to be able to explain why or how you came to the conclusion you did. So, first, you’d to know not just what you think, but why you think it—what evidence you have for it. Second, you’d need to be able to step back from your belief about Canadians and think about whether it’s a reasonable way to think. If you said, “Well, every Canadian I’ve ever known loves rap,” I might say, “How many have you known?” And we might end up talking about whether generalizing from three people is a good way to draw a conclusion about a nation of millions. You’d need to be able to engage in metacognition.

A productive disagreement doesn’t just involve our giving one another reasons for what we believe, but being willing to think about whether the sorts of reasons we’re giving are good.[12]

If one of us is deeply committed to refusing to change our mind on the issue,[13] then we’ll keep the conversation from going to issues of the major premise or metacognition. If, for instance, you have told me that you think this little dog is good, and I’m a devoted Chesterian, then my most likely response is to attack you—“What are you, some kind of Hubertian?!” I might try to persuade you that your sense of your self as a good Chesterian would never like a little dog. My “What are you, some kind of Hubertian?” is a compressed set of claims:

-

- only Hubertians say anything good about any little dogs;

- being a Hubertian is bad.

That’s a pretty crummy argument, but it’s likely to persuade you that the dog isn’t cute (that is, to retract your claim) under various circumstances:

-

- If, for instance, I’m a member of the Big Dog Police, and you have good reason to think you might end up beaten up or jailed for disagreeing with me;

- if I’m your boss, and you have good reasons based on previous experience to think expressing affection for little dogs is likely to result in getting fired or being treated badly (even though I didn’t say that in this conversation);

- if being seen as a good member of the Chesterians is economically, spiritually, or culturally important to you (such as your living in the Big Dog Co-op, and getting known as a Hubertian could get you thrown out of the community);[14]

- any other circumstances in which disagreeing with me might have high costs;

- if you believe the two claims above.

Notice the number of things that will influence even these factors—whether I’m slapping a nightstick in my hand as I ask you, whether I seem angry, amused, threatening, kidding; how well we know each other, what our previous experience with each other is.

And I don’t even necessarily need to get you to retract your claim mentally, if I can persuade you to shut up and never say anything positive about little dogs again. We don’t often talk about that kind of persuasion but it’s important (and it’s especially important for understanding how rhetoric worked in Nazi Germany). I can persuade you to change your mind, or I can persuade you to change your behavior. In lots of circumstances, the latter is enough: if I persuade you never to defend little dogs, never say good things about them, never to identify or empathize with them, then I have gone a long way toward enabling a culture in which they are vilified, mistreated, expelled, or exterminated.

Persuading someone to be silent is a powerful kind of persuasion. And it’s one at which the Nazis excelled.

This is a slightly broader notion of rhetoric than many people have, since they think of rhetoric as only compliance-gaining policy advocacy. Aristotle said rhetoric is the study of the available means of persuasion, and, if I persuade you to stop defending little dogs by threatening you, then, by Aristotle’s argument, we need to include threatening as a kind of rhetoric (and I think we should). It’s ultimately a harmful one (but so is compliance-gaining), but it’s still one.

Another kind of rhetoric that people don’t always consider is sometimes called deliberation or, the term I prefer, good faith argumentation. In good faith argumentation, people are open to changing their minds, feel obligated to provide evidence and make internally consistent arguments, apply the rules the same across all interlocutors, avoid implicit or explicit threats, try to represent one another’s arguments fairly, strive to be accurate and honest (those aren’t always the same things), and otherwise follow the rules set out by the pragma-dialectical school.

- Parties must not prevent each other from advancing standpoints or casting doubt on standpoints.

- A party that advances a standpoint is obliged to defend it if the other party asks him to do so.

- A party’s attack on a standpoint must relate to the standpoint that has indeed been advanced by the other party.

- A party may defend his standpoint only by advancing argumentation relating to that standpoint.

- A party may not falsely present something as a premise that has been left unexpressed by the other party or deny a premise that he himself has left implicit.

- A party may not falsely present a premise as an accepted starting point nor deny a premise representing an accepted starting point.

- A party may not regard a standpoint as conclusively defended if the defense does not take place by means of an appropriate argumentation scheme that is correctly applied.

- In his argumentation, a party may only use arguments that are logically valid or capable of being validated by making explicit one or more unexpressed premises.

- A failed defense of a standpoint must result in the party that put forward the standpoint retracting it, and a conclusive defense of the standpoint must result in the other party retracting his doubt about the standpoint.

- A party must not use formulations that are insufficiently clear or confusingly ambiguous and he must interpret the other party’s formulations as carefully and accurately as possible.[15]

Following these rules is especially effective for policy argumentation. Policy argumentation involves someone make an affirmative argument for a plan and then people debating that case (or proposing another plan). An affirmative case requires:

-

- a coherent narrative about there being a problem and what has caused it to happen (a narrative of causality) so policy argumentation requires that the rhetor(s) show

- there is a significant problem (stock issue of significance)

- and it will not go away on its own (inherency)

- and it is a structural problem (so the solution must involve structural changes—structural inherency)

- or, it’s an attitudinal problem (the people enacting policies have the wrong attitude—attitudinal inherency)

- a description of the plan and arguments (not just assertions) that the plan

- is feasible (it’s practical and possible within various constraints),

- will actually solve the problem (solvency),[16]

- will not have unintended consequences that make the plan cause more problems than it solves.

A negative case is one that disagrees at any or all of these points (these stock issues). It might dispute that there is a problem, or say that the affirmative case has the wrong narrative of causality (in which case the plan can’t work), or say the problem will go away if we give it time, argue the plan isn’t feasible, doesn’t solve the problem, or will have more costs than benefits.

One thing you should to which you should pay attention as you’re reading material for this class is whether rhetors are engaged in good faith argumentation and/or policy argumentation. What you’ll see is that they generally aren’t, and that’s interesting

3. Hitler’s rhetoric

As Nicholas O’Shaughnessy says, anyone looking at the devastation of World War II and the Holocaust is likely to wonder: “How was it possible for a nation as sophisticated as Germany to regress in the way that it did, for Hitler and the Nazis to enlist an entire people, willingly or otherwise, into a crusade of extermination that would kill anonymous millions?” (1) One answer, the one you’d probably get if you stopped someone on the street, is to attribute tremendous rhetorical power to Adolf Hitler. Kenneth Burke calls Hitler “a man who swung a great deal of people into his wake” (“Rhetoric” 191). William Shirer, who was an American correspondent in Germany in the 30s, describes that, listening to a speech he knew was nonsense, “was again fascinated by [Hitler’s] oratory, and how by his use of it he was able to impose his outlandish ideas on his audience” (131). Shirer says Hitler “appeared able to swing his German hearers into any mood he wished” (128). Shirer is clear that Hitler owed his power to his rhetoric: “his eloquence, his astonishing ability to move a German audience by speech, that more than anything else had swept him from oblivion to power as dictator and seemed likely to keep him there” (127). In this view, Hitler was (and is) the cause of the war and serial exterminations.

Scholars don’t necessarily agree, however. Ian Kershaw says, “Hitler alone, however important his role, is not enough to explain the extraordinary lurch of a society, relatively non-violent before 1914, into ever more radical brutality and such a frenzy of destruction” (Hitler, The Germans, and the Final Solution 347). While Hitler’s personal views were important, and neither the Holocaust nor war would have happened without his personal fanaticism and charisma, they weren’t all that was necessary:

Concentrating on Hitler’s personal worldview, no matter how fanatically he was inspired and motivated by it, cannot readily serve to explain why a society, which hardly shared the Arcanum of Hitler’s “philosophy,” gave him such growing support from 1929 on—in proportions that rose with astonishing rapidity. Nor can it explain why, from 1933 on, the non-Nationalist Socialist élites were prepared to play more and more into his hands in the process of “cumulative radicalization.” (Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution 57)

In other words, Hitler’s followers were not passive automatons controlled by Hitler’s rhetorical magic. So, how powerful was that rhetoric?

The answer to that question is more complicated than conventional wisdom suggests for several reasons. First, while Hitler was quick to use new technologies, including ones of travel, most of the Nazi rhetoric consumed by converts wasn’t by Hitler. People like Adolf Eichmann talk about being persuaded by other speakers, pamphlets, even books.

Second, no one claims that Hitler was a creative or inventive ideologue: “Hitler was not an originator but a serial plagiarist” (O’Shaughnessy 24). Joachim Fest said Hitler’s beliefs were the “sum of the clichés current in Vienna at the turn of the century” (qtd. in Gregor, 2), and Gregor says, “Neither can one claim that Hitler was an original thinker. There is little in his writings or speeches that we cannot find in the penny pamphlets of pre-1914 Vienna where he began to form his political views. His racial anti-Semitism rehearses the familiar slogans of many on the pre-war right. His visions of German expansion echo the ideas of the more extreme wing of the radical-nationalist Pan German movement [….] And, in essence, his anti-democratic, anti-Socialist sentiments similarly reproduce the conventional thinking of broad sectors of the German right from both before and after the First World War.” (2)

If Hitler wasn’t saying anything new, to what extent can we say he persuaded people? What did he persuade them of?

A closely related problem is that large numbers of Germans supported Hitler politically but rejected the central aspects of his ideology—such as his eliminationist racism and his desire for another war. Although he’d long been absolutely clear that those were central to his views, when he began to downplay them (especially in 1932 and 33), many people believed those were trivial aspects that could be ignored. Many people supported him strategically, especially the Catholic and Lutheran churches, both of which were outraged by the Social Democrats’ (democratic socialists) liberal social policies (e.g., legalizing homosexuality, supporting feminism, and, especially, breaking the religious monopoly on primary schools). Since Hitler and the Nazis were socially conservative, and Hitler promised to allow the churches more power than the Social Democrats would allow, many Protestants voted for Nazis, and the official Catholic Party (the Centre Party) Reichstag members voted unanimously for Hitler taking on dictatorial power (for more on this background, see Evans; Spicer).

Some scholars refer to “the propaganda of success,” by which they mean that Hitler gained the support of people not because he put forward good arguments, or even because of anything he said, but because they liked his locking up Marxists and Socialists, industrialists liked his support of big business, people liked the increased amount of order, they liked the improved economy, they liked his conservative social policies, a lot of Germans liked his persecution of immigrants, and a lot of people either liked or didn’t mind the legitimating and legalizing of discrimination against Jews (even the churches only objected to discrimination against converted Jews). And large numbers of Germans didn’t particularly like the idea of democracy—the premise of democracy is that political situations are complicated, and that there aren’t obvious solutions. Or, more accurately, there are solutions that appear to be obviously right from one perspective, but are obviously wrong from another perspective. Democratic processes assume that the various perspectives need to be taken into consideration, and so the best policy for the community as a whole will not be perfect for anyone and will take a lot of time to determine—many people would rather that a powerful leader make all the decisions and leave them out of it. After Hitler had been in power a year, many people felt that their lives were better, and that’s all they really cared about—that they were headed down a road that would make their lives much worse didn’t concern them because they didn’t think about it.

Finally, many people came to support Nazis because they liked that Hitler made them feel proud of being German again. He didn’t make them feel proud of being German by changing their minds about anything, but by insisting publicly and endlessly that they were victims—that nothing about their situation was the consequence of bad decisions they had made. He wasn’t saying anything that was new, but it was new for a political leader—he was simply the first major German political figure in a long time to say, unequivocally, Germany was for Germans, and Germans were entitled to run Europe (if not the world).

All these characteristics of Hitler’s relationship with his supporters—his lack of originality, strategic acquiescence, hostility to democracy, narrow self-interest on the part of many Germans, and the propaganda of success—mean that it’s actually an open question as to whether Hitler’s rhetoric was unique, let alone how much power we should ascribe to it.

Hitler did persuade people—people did act in ways that they wouldn’t have acted had it not been for him—but he didn’t do so through a single speech, nor on his own, nor even just through discourse. Hitler had a lot of “available means of persuasion” (to go back to Aristotle’s definition of rhetoric) and he used them. As mentioned before, Hitler didn’t necessarily have to get everyone (or even most people) to believe Nazi ideology; he had to get people to comply with Nazi policies, or at least not resist them. If they did believe the ideology, their compliance with the policies was likely to be more thorough, predictable, and less expensive, but belief wasn’t necessary. Someone who sincerely believed that all Jews were communist terrorists working to undermine Germany could be counted on to inform on neighbors, and might help round some up, but someone who sincerely believed that intervention was certain death could be counted on to stand idly by, and that was good enough.

For instance, Hitler persuaded the Germany military forces to support him, to fight to the very last, following orders that many of them believed were unwise. And he did so with various means. Robert Citino explains the German officer corps’ willingness to “be with him every step of the way:”

Although they were not all Nazis, and Hitler had not captivated them all in a personal sense, his sensibilities and his policies—antisocialism, anti-Bolshevism, and anti-Semitism—had produced at least a “partial identificiation” (Teilidentität) with his regime. His early successes had impressed them all: rearmament and restoration of German sovereignty; a series of bloodless border conquests, and then a refight of World War I against Britain and France. Next came an existential struggle against the Soviet Union in which the Wehrmacht obliterated all the customary, legal, ethical, and moral boundaries of modern war. Enough of them supported Hitler’s crusade against Bolshevism to suppress whatever scruples they might have felt about his call for an ‘annihilation struggle’ (Vernichtungskampf) in the east. Finally, there was a global struggle against every great power that Hitler could find, and he found a lot of them. Gradually, as things went bad, some began to mutter, and a small number of them decided to kill him. (281).

Notice that Citino is emphasizing that the members of the officer corps were persuaded to support Hitler and enact his decisions without necessarily believing his decisions were right, his strategy was correct, or even he was a good person. Some had blind faith in Hitler, some believed they were already in too deep, some believed it would be an impossible dishonor to violate the oath they had taken, some believed they had no choice. Hitler just had to persuade the members of the officer corps to follow his orders; he didn’t have to persuade them the orders were good.

It’s important to remember that one of the available means of persuasion is a credible threat of violence. For a threat to get compliance, the audience has to believe it’s credible, so there is an aspect of belief involved—but that belief can be as much a consequence of action as discourse. Threats of violence against dissenters and critics of the Nazi regime because Germans would have seen them carried out.

Kershaw argues that people continued to fight when surrender would have been much more sensible for several main reasons:

-

- true believers thought that Hitler had some kind of weapon about to be released, or that he would, as he had in the past, find a way to save an apparently impossible situation

- some true believers thought that the US and UK could not keep working together and/or remain allied with the USSR, and so the alliance would crack at the crucial moment (as they believed had happened with Frederick the Great)

- large numbers of people believed that, especially given how exterminationist their war had been, their victors would exterminate them (in other words, a kind of pro-active projection—the victors would treat the Germans as badly as the Germans had treated others)

- large numbers of people believed they had no choice, that they would be killed or imprisoned if they did anything other than fight

- some people were motivated by the belief that loyalty to nation is the highest value, even if the nation has been exterminationist

Notice that few of those beliefs were peculiar to Hitler, that they were rhetorically effective because they were widespread. Nazi rhetoric depended on several widespread beliefs—Nazis didn’t invent these beliefs, but relied on them:

-

- the notion that Germany was entitled to European hegemony,

- that it was “encircled” by hostile countries,

- that it should have and could have won WWI (and was just about to)

- when it was “stabbed in the back” by a Jewish media,

- normalized antisemitism,

- anti-liberalism,