Among Democrats, there are a lot of narratives about the 2016 election, and two of them are highly factional (that is, they assume an us or them, with us being the faction of truth and beauty and them being the people who are leading us astray). One is that Clinton’s election was tanked by Bernie-bros who were all young white males too obsessed with purity to take the mature view and vote for Clinton. The other is that the DNC, an aged and moribund institution, foisted Clinton onto Dems when she was obviously the wrong candidate.

Both of those narratives are implicit calls for purity, for a Democratic Party (or left) that is unified on one policy agenda—maybe the policy agenda is a centrist one, and maybe it’s one much further left—but the agreement is that we need to become more purely something. Both narratives are empirically false (or else non-falsifiable), patronizing, and just plain offensive. In other words, both of those narratives are driven by the desire to prove that “us” is the group of truth and goodness and “them” is the group of muddled, fuddled, and probably corrupt idjits.

And, as long as the discourse on the left is which “us” is the right us, progressive politics will lose.

There isn’t actually a divide in the left—there’s a continuum. People who can be persuaded to vote Dem range from authoritarians drawn to charismatic leadership (anyone who persuades them that s/he is decisive enough to enact the obviously correct simple policies the US needs) all the way through various kinds of neoliberalism to some versions of democratic socialism. And there are all those people who can vote Dem on the basis of a single issue—abortion or gun control, for instance. When Dems insist that only one point (or small range) on that continuum is the right one, Dems lose because none of those points on the continuum has enough voters to win an election. That’s why purity wars among the Dems are devastating.

While voting Dem is actually a continuum, there are many who insist it is a binary—those whose political agenda the DNC should represent (theirs) and those whose agenda is actually destructive, whose motives are bad, and who cause Dems to lose elections (everyone else—who are compressed into one group).

Here’s what’s interesting to me. It seems to me that everyone who wants Dem candidates to win recognizes that a purity war on the left is bad, and everyone condemns it. Unhappily, being opposed to a purity war in principle and engaging one in effect are not mutually exclusive. There is a really nasty move that a lot of people make in a rhetoric of compromise—we should compromise by your taking my position—and that is what a lot of the “let’s not have a purity war” on the left seems to me to be doing. Let’s not do that. Let’s do something else.

This is about the something else that we might do.

And it’s complicated, and I might be wrong, but I think that Dems will always lose in an “us vs. them” culture because, at its heart, the Dem political agenda is about diversity and fairness, and people drawn to Dem politics tend to value fairness across groups more than loyalty to the ingroup, so any demagogic construction of ingroups and outgroups is going to alienate a lot of potential Dem voters. Sometimes voting Dem is a short-term looking out for your own group, but an awful lot of Dem voters are motivated by the hope of creating a world that includes them. I don’t think Dems will succeed if we grant the premise that Dem politics are about resisting: that only the ingroup is entitled to good things.

But we’re in a culture of demagoguery, in which politics is framed as a battle between Good and Evil, and deliberation (in which people of different points of view come together to work toward a better solution) that we’re in a world of us vs. them, how can Dems create a politics of us and them? That is our challenge.

And I want to make a suggestion about how to meet that challenge that is grounded in my understanding of what has happened in the past, not just 2016 (although that is part), but also to ancient Athens, to opponents of Andrew Jackson, to opponents of Reagan, and in the era of highly-factionalized media. I want to argue that what seem to be obviously right answers are not obvious, and possibly not even right.

1. In which I watch lefties tear each other to shreds and lose an election we should have won

When I first began to pay attention to politics, and saw how murky, slow, and corrupt it all was, it seemed to me that the problem was clear: people started out with good principles, and then compromised them for short-term gains, and so, Q effing D, we should never compromise. (I saw The Candidate as a young and impressionable person.)

I could look at political issues, and see the obvious course of action. And I could see that political figures weren’t taking it. Obviously, there was something wrong with them. Perhaps they were once idealistic, perhaps they had good ideas, but they were compromising, and, obviously, they shouldn’t; they should do the right thing, not the sort of right thing.

Another obvious point was how significant political change happens: someone sets out a plan that will solve our problems, and refuses to be moved. ML King, Rosa Parks, FDR, Woodrow Wilson, John Muir, Andrew Jackson (no kidding—more about his being presented as a lefty hero below) were all people who achieved what they did because they stood by their principles.

That history was completely, totally, and thoroughly wrong, in that neither Wilson nor Jackson were the progressive heroes I thought and that all of those figures compromised a lot, but, if that’s the history you’re given then you will believe that to compromise necessarily means moving from that obviously right plan (about which you shouldn’t have compromised) to one that is much less right, and the only reason to do that would be pragmatic (aka, Machiavellian) purposes. Therefore, substantial social change and compromise are at odds, and if you want substantial social change, you have to refuse to compromise. (Again, tah fucking dah—there’s a lot of that in easy politics.)

My basic premise was that the correct course of action was obvious, and, therefore, I had to explain why political figures didn’t adopt it. Why would people compromise a policy that is obviously right? And, obviously, they had to deviate from the right course of action in order to get political buy-in from people who value things I don’t value. Or they were bad politicians in the pocket of corporate interests. (Notice how often things seemed obvious to me.)

And then Reagan got elected. Reagan lied like a rug, and yet one of the first things his fans said about him was that he was authentic. He announced his run for Presidency by saying he would support states rights at the site of one of the most notorious civil rights murders. And yet his fans would get enraged if you suggested he appealed to racism.

People loved him, regardless of his policies, his actual history, his lies. They loved his image. (It’s still the case that people admire him for things he never did.)

When he was elected, lefties went to the streets. We protested. The people protesting were ideologically diverse—New Deal Dems, people who had said that there was no difference between him and Carter, radical lefties, moderate lefties, I even saw people who told me they intended to vote for Reagan because it would make the peoples’ revolution more likely, and they were now protesting that the candidate they had supported had won.

There were more than enough people out protesting Reagan’s election to prevent his getting reelected. And, in 1980, we all agreed that he shouldn’t be reelected. Unhappily, we also all agreed that he had been elected because there was too much compromising in the Dem party, that Carter was a warmongering tool of the elite, and the mistake we made was not have a candidate who was pure enough. And, so, we agreed, the solution was for the Dems to put forward a Presidential candidate who was more pure to the obviously right values and less willing to compromise on them. We didn’t get that candidate, we didn’t get a very good candidate in fact (he was pretty boring), but his policies would have been good. And a lot of lefties refused to vote for him.

Unhappily, it turns out we disagreed as to what those obviously right values were.

In 1980, the Democratic Party was the party of unions, immigrants, non-whites, people who believe in a strong safety net, isolationists, humanitarian interventionists, pro-democracy interventionists, people who believe a strong safety net was only possible in a strong economy (what would be later be called third-way neoliberals), environmentalists, people who were critical of environmentalists, and all sorts of other ideologically diverse people.

There wasn’t a party platform on which we could all agree. To support the unions more purely would have, union reps argued, meant virulently opposing looser standards about citizenship and immigration. The anti-racist folks argued for being more inclusive about citizenship and immigration. Environmentalists wanted regulations that could cause manufacturing to move to countries with lower standards, something that would hurt unions. People who wanted no war couldn’t find common ground with people who wanted humanitarian intervention. (And so it’s interesting how conservative the 1980 platform now looks.)

Dems, at that point, four choices: reject the notion that there was a single political agenda that would unify all of its groups (that is, move to a notion of ideological and policy diversity in a party); decide that one group was the single right choice; try to find someone who pleased everyone; try to find candidates who wouldn’t offend anyone; or engage in unification through division (get people to unify on how much they hated some other group).

Mondale was the fourth, most lefties went for the second or fifth. I think we should consider the first.

At the time I was a firm believer in the second, for both good and bad reasons. And lots of other people were too. What we believed is what I have come to think of as the P Funk fallacy: if you free your mind, your ass will follow. I believed that there were principles on which all right-thinking people agree, and that those principles necessarily involve a single policy agenda. Thus, we should first agree on principles, and then our asses will follow.

Lefty politics is the grandchild of the Enlightenment. We believe in universal rights, the possibilities of argument, diversity as a positive good, the hope of a world without revenge as the basis of justice. And, perhaps, we have in our ideological DNA a gene that is not helping us—the Enlightenment is also a set of authors who shared the belief (hope?) that, as Isaiah Berlin said, all difficult questions have a single true answer. I think the hope is that, if we get our theories right—if we really understand the situation—then the correct policy will emerge.

But, there might not be a correct policy, at least not in the sense of a course of action that serves everyone equally well. An economic policy that helps creditors will hurt lenders, and vice versa.[1] In trying to figure out then what kind of economic policy we will have, we can decide we’re the party of lenders, or we’re the party of borrowers, and only support policies that help one or the other. Or, we could be the centrist party, and try to have policies that kinda sorta help everyone a little but not a lot and therefore kinda sorta hurt everyone a little but not a lot. And thereby we’re promoting policies that everyone dislikes—I think Dems have been trying that for a while, and it isn’t working. But neither is deciding that we’ll only be the party of borrowers, since borrowers require lenders who are succeeding enough to lend.

The problem with the whole model of politics being a contest between us and them is that it makes all policy discussions questions of bargaining and compromise. What’s left out is deliberation. But that’s hard to imagine in our current world of, not just identity politics, but of a submission/domination contest between two identities. And, really, that has to stop.

Blaming the left for identity politics is just another example of the right’s tendency toward projection. The Federalist Papers imagines a world in which elections are identity-based (which the Constitution’s defenders saw as preferable to faction-based voting). Since most voters could not possibly personally know any candidate for President or Senate, they should instead vote for someone they could know, and whose judgment they trusted (see, for instance, what #64 says about the electors and the Senate). That person could then know the various candidates and make an informed decision as to which of them had better judgment. So, at each step, people are voting for a person with good judgment, to whom they were delegating their own deliberative powers.

That vision quickly evaporated and was replaced by exactly what the authors of the Constitution had tried to prevent: party politics. And then, by the time of Andrew Jackson, we got a new kind of identity politics: voting for a candidate because he seems to share your identity, and, will therefore look out for people like you. His good judgment comes not from expertise, the ability to deliberate thoughtfully, or deep knowledge of history, but from his being an anti-intellectual, successful, and decisive person who cares about people like you. Through the nineteenth century, the notion of an ideal political figure shifted from someone much smarter than you are to someone not threatening to you.

2. Factionalism, Andrew Jackson, and the rise of identification

The problem that everyone to the left of the hard right has is the same: that we are in a culture in which rabid factionalism on the part of various right-wing major media is normalized, and anything not rabidly right-wing is condemned as communist. Lefties should be deeply concerned about factionalism (including our own), and careful about how we try to act in such a world. There is are several clear historical lessons for Americans as to what that kind of rabid factionalism does (I’ll just talk about Athens), and a clear lesson from American history as to how we should not try to manage it (the case of Andrew Jackson).

Here’s the short version. The US, when it was founded, was an extraordinary achievement on the part of people well-versed in the histories of democracies, republics, and demagoguery. Their major concern was to make sure that the US would not be like the various republics and democracies with which they were familiar. That included the UK (which was, at that point, immersed in a binary factionalism), various Italian Republics (especially Florence and Venice), the Roman Republic, and Athens.

And Athens is an interesting case, and something about which current Americans should know more. Knowing their Thucydides (via Thomas Hobbes, a post I might write someday), the authors and defenders of the constitution knew that Athens had shot itself in the face because at a certain point (just after the Mytilenean Debate, for those of you who care), everyone in Athens thought about politics in two ways: 1) what is in it (in the short-term) for me; 2) what will enable my political party to succeed?

No one worried about “what is best for Athens” with a vision of “Athens” that included members of the other political party. So, because Athens was in a situation of rabid factionalism, you would cheerfully commit troops to a political action if you thought it would do down the other party. Military decisions were made almost entirely on factional bases.

Thucydides describes the situation. He says that city-state after city-state broke into hyper-factional politics that was almost civil war. All anyone cared about was whether their party succeeded—no one listened to the proposals of the other side with an ear to whether they were suggesting something that might actually help. In fact, being willing to listen to the other side, being able to deliberate with them, looking at an issue from various sides—all of those things were condemned as unmanly dithering. Refusing to call for the most extreme policies or suggesting moderation wasn’t a legitimate position—anyone doing that was just trying to hide that he was a coward. Only people who advocated the most extreme policies was trustworthy; anyone else wasn’t really loyal to the party and so shouldn’t be trusted. Plotting on behalf on the party was admirable, and it didn’t matter how many morals were shattered in those plots—success of the party justified any means. But people weren’t open that they were willing to violate every ethical value they claimed to have in order to have their party triumph; people cloaked their rabid factionalism in ethical and religious language while actually honoring neither. So, Thucydides says, there was a situation in which every good value was associated with your party triumphing, and every bad value associated with their not triumphing.

People worried about their party, and not their country.

We can think, why would anyone do that? And yet, we might do it. No one thought to themselves, “I wish to hurt Athens and so I will only look out for my political party.” Instead, what they probably never thought, consciously, but was the basis for every decision was that only their group was really Athenian. So, they thought (and sincerely believed) anything that promotes the interests of my group is good for Athens because only my group is really Athenian.

Michael Mann, a scholar of genocides, calls this the confusion of ethos and ethnos. The “ethos” of a country is the general culture, and the “ethnos” is one particular ethnic group. What can happen is that specific group decides that it is the real ethos, and therefore any action against other groups is protecting “the people.” They are the only “people” who count. Seeing only your class, political party, ethnic group, or religion as the real identity of the group hammers any possibility of inclusive deliberation. It is also the first step toward the restriction, disempowerment, expulsion, and sometimes extermination of the non-you. While not every instance of “only us counts” ends in mass killing, every kind of mass killing—genocide, politicide, classicide, religoicide—begins with that move.

Even ignoring the issue of the ethics of that way of thinking, it’s a bad way for a community to deliberate. But what they did think, as Thucydides says, is that anything that helped you and your party was a good thing to do, even it was something you would condemn in the other party. You might cheerfully use appeals to religion to try to justify your policies, but if other policies better helped your party, then you’d use religion to justify those policies. No principle other than party mattered.

If the other side proposed a policy, you didn’t assess whether it was a good policy, you were against it. You were especially likely to be against it if it was a good policy, since then they would gain more supporters. You would gleefully gin up a reason that troops should be sent to a losing battle and put an opposition political figure in charge—losing troops (and a battle) was great if it hurt the party.

And so Athens crashed. Hardly a surprise.

In fact, the people of Athens were dependent on each other, and no group could thrive if other groups lost battles. Us and Them thinking forgets that we are us.

At the time of the American Revolution, the British political situation was completely factionalized. We might like to admire Edmund Burke, who so eloquently defended the American colonies, but even I (an admirer of his) know that, had his party been in good with George III (they weren’t) he probably would have written just as eloquent an argument for crushing the American Revolution. The authors of the Constitution were also well aware of other historical examples that showed the fragility of republics, especially Venice (one of the longest lasting republics), Florence, and Rome.

And those were the conditions the authors of the Constitution tried to solve through the procedure of people voting for someone whose authority came from intelligence and judgment. That is, the constitution worked by having people vote, not for the President directly (since you couldn’t possibly know the President personally) but for someone you could know—a state legislator, an elector—whose judgment you could assess directly. But factions arose anyway.

The factions were somewhat different from those in either Athens or Britain. In Athens it was (more or less) the rich who wanted an oligarchy, or really a plutocracy, with the wealthy having more power than the poor, and with very little redistribution of wealth. On the other side were the non-leisured (not necessarily poor, but not very wealthy either) who wanted at least some redistribution of wealth and a lot of power-sharing. But an individual’s decision to join a particular faction was also influenced by family alliances and personal ambition. In Britain, factions were described as country versus city (wealth that came from land ownership versus industry and finance) which may or may not be accurate. As in Athens, there were other factors than just economics, and that city-country distinction might itself have been nothing more than good rhetoric to explain factions that weren’t really all that different from each other.

In the US, by the time of Andrew Jackson’s rise (the 1820s), there was some division along economic lines (agriculture vs. shipping, for instance), and some along ideological ones (Federalist vs. Antifederalist), but they didn’t give a very clean binary. There were more than two parties, and even the major parties were coalitions of people with nearly incompatible political agenda (Whigs and Democrats were both strong in the North and South, for instance). Given both the youth of the country and the large number of immigrants, there weren’t necessarily family traditions of having been in one faction or another, and there wasn’t some kind of regional distinction (the North was still predominantly agricultural, and some “Northern” states had slaves until the 1830s, so neither the agricultural/industrial nor slave/not slave distinctions provided any kind of mobilizing policy identity). There wasn’t the odd role that the monarchy played in British political factions (for years, one faction attached to the monarch, and another to the son whom the monarch hated). US factions were muckled and shapeshifting.

A disparate coalition is particularly given to intrafactional fighting, splitting, and purity wars, and so there is generally a strong desire to find what is usually called a “unification device.” The classic strategy to unify a profoundly disparate coalition is two-part: unification through finding a common enemy; cracking the other side’s coalition with a wedge issue. If a party is especially lucky, that two-part strategy is made available through one issue. And that’s what US parties did in the antebellum era, and, after trying various ones, they ended up on fear-mongering about abolitionism, with some anti-Catholicism thrown into the mix.

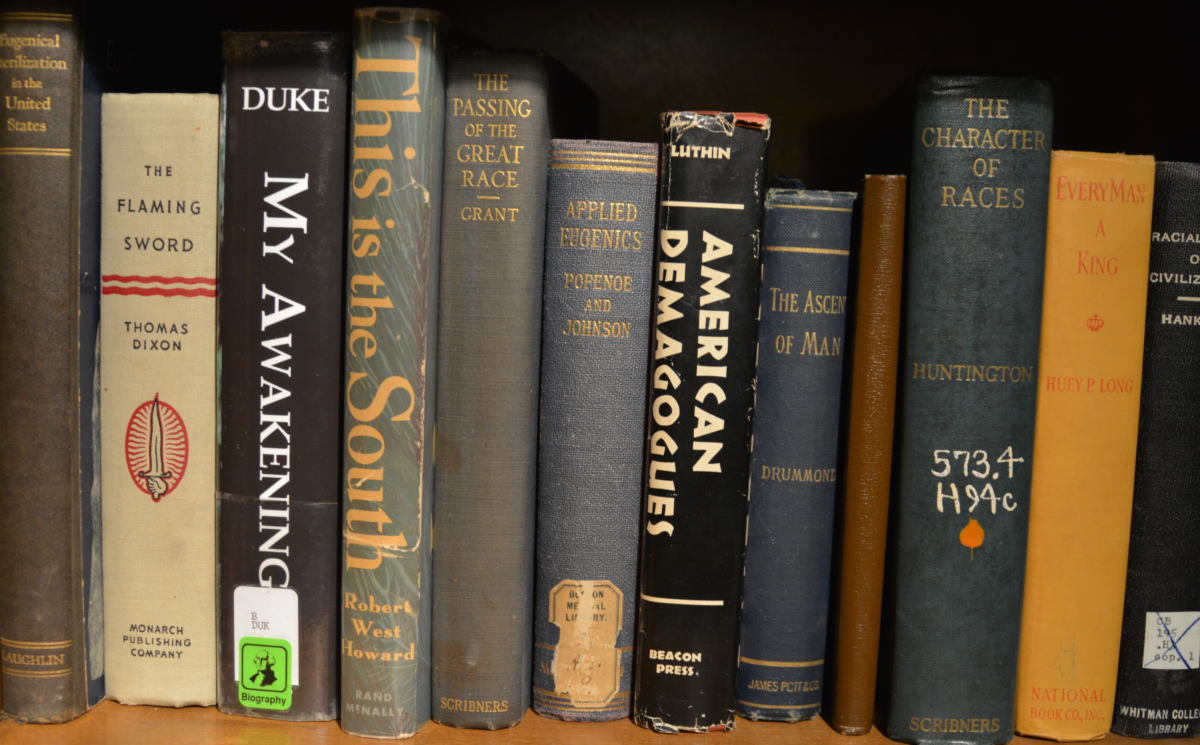

Antebellum media was extremely factionalized. Newspapers were simultaneously openly allied with a particular party, rabidly factional, and passionate in their condemnations of faction.

“The bitterness, the virulence, the vulgarity, and perfidy of factious warfare pervade every corner of our country;–the sanctity of the domestic hearth is still invaded;–the modesty of womanhood is still assailed…” (“Party” U.S. Telegraph, June 24, reprinted from the Sunday Morning News). The anti-Jackson Raleigh Register had the motto “Ours are the plans of fair delightful peace, unwarp’d by party rage, to live like brothers” but spent the spring and early summer of 1835 in vitriolic exchanges with the Jacksonian Standard. One letter in the exchange, for instance, begins, “The writhing, twisting and screwing–the protestation, subterfuge and unfairness and the lamentation, complaint and outcry displayed in this famous production” (Raleigh Register February 10, 1835). (From Fanatical Schemes).

For instance, a newspaper’s criticism of a political party inspired a member of that party to threaten a duel, and, once the various rituals had been enacted that enabled a duel to be avoided, the person who had threatened a duel over his political faction having been criticized said, “I regard the introduction of party politics as little less than absolute treason to the South.”

When, from about 2003 to 2009, I was working on a book about proslavery rhetoric, this characteristic—that people operating on purely factional motives condemned factionalism—was one of the characteristics that made me begin to worry about current US political discourse, since it was so true of what I was seeing in American media. The most passionately factional media have mottos like “Fair and Balanced.” I have an acquaintance who consumes nothing but the hyper-factionalized media, and he has several times told me I shouldn’t believe something not-that-media because it’s “biased.” Clearly, he doesn’t object to biased media, since that’s all he consumes. And then I noticed that’s a talking point in various ideological enclaves—you refuse to look at anything that disagrees with the information you’ve gotten from your entirely biased sources on the grounds that they are biased.

If you push them on that issue, I’ve found that consumers of that extremely factional media respond to criticisms of their factionalism (and bias) with “But the other faction does it too”—a response that only makes sense in which every question is “which faction is better” not “what behavior is right.” So, even their defense of their factionalism shows that, at the base, they think political discourse is a contest between factions, and not a place in which we should—regardless of faction—try to consider various policy options. They live and breathe within faction.

Andrew Jackson was tremendously successful in that world, partially because of his conscience-free use of the “spoils system”—in which all governmental and civil service positions were given to supporters. And Jackson didn’t particularly worry about his policies; one of his major “policy” goals was abolishing the National Bank. Scholars still argue about whether he had a coherent political or economic policy in regard to the bank; what is clear is that he didn’t articulate one, nor did his supporters. Hostility to the bank was what might be called a “mobilizing passion,” not a rationally-defended set of claims. But that passion was shared with many who had almost gut-level suspicions of big banks, monetary controls, and a strong Federal Government.

It was such a widely-shared view that Jackson’s destruction of the Bank, and its direct consequence, the Panic of 1837, couldn’t serve as a rallying point for his opposition. And Jackson’s combination of popularity, use of the spoils system (including his appointment of judges—one of whom is an ancestor of mine), and strong political party worried many reasonable people that he was trying to create a one-party state. So, even as his second term was ending, people were trying to figure out how to reduce his power, and yet they couldn’t use what was quite clearly unsound economic policies.

There were more opponents of Jackson than there were supporters, but to call them disparate is an understatement. Some were pro-Bank, but too many were anti-Bank for that issue to be useful. There were a large number of anti-Catholics (some of whom might have been Masons), and also a few anti-Masons. Jackson’s bellicose (albeit effective) handling of the Nullification Crisis had alienated many of the South Carolina politicians whom he had trounced, but their stance on the tariffs (which had catalyzed the Nullification Crisis—they were trying to nullify tariffs) was incompatible with manufacturers in other areas.

Jacksonian Democrats played two (related) cards quite effectively—they played to racism about African Americans by supporting disenfranchisement of African-American voters and engaging in fear-mongering about free African Americans at the same time that openly embraced Irish-Catholic voters (whose right to vote was still an issue in some places). They thereby drove a wedge between two groups that might have allied (poor Irish and freed African Americans), essentially offering the gift of “whiteness” to the Irish for their political support (this story is elegantly and persuasively told in How the Irish Became White). Because politics naturally works by opposites, this made Catholicism an issue on which other parties had to take a stand, and they stood to lose large numbers of voters no matter which way they jumped. The only thing that the various anti-Jackson parties shared was that they were anti-Jackson, and it’s hard to raise a lot of ire against a white guy who does a good job of coming across as a regular guy who really cares about “normal” people. In rhetoric, that’s called “identification”—a rhetor persuades an audience that s/he and they share an identity, and persuades them that the shared identity is all the information the audience needs.[2]

Elsewhere I’ve argued that John Calhoun tried to use fear-mongering about abolitionists (who were a harmless fringe group at that point) in order to unify proslavery forces behind him. It’s a great kind of strategy—you find some kind of hobgoblin that is politically powerless but that frightens a politically powerful group, and you present yourself as the only one who can save them from that hobgoblin. Unfortunately for everyone, Calhoun’s opponents simply picked up his method and American politics began an alarmism race to see who could out-fearmonger the others and call for increasingly extreme (and irrational) gestures of loyalty to slavery. Eventually, those gestures (such as the Fugitive Slave Law, the “gag rule,” the attempt to expand slavery past the Mason-Dixon Line, and, finally, the Dred Scott decision) generated as much fear and anger about The Slave Power as proslavery rhetors were generating about abolitionists.

Reagan was much like Jackson, in that his economic policies were vague but seemed populist, and he persuaded people that he really cared about them and understood them. He was normal, and he wanted normal Americans to be at the center of America.

Trump’s situation is different in that he has never had very high approval outside of his faction, but the rabidly factionalized media ensures that he has a deliberately and wickedly misinformed faction who are willing to pivot quickly for a new posture on a political issue.

What makes the two people similar, and like Jackson, is just that they have far more opponents than they have allies, and a highly mobilized base. As long as the opposition remains internally factionalized, they win. But, at this point, all that is shared among Trump’s opponents is opposition to Trump. The impulse might be to try to do what Jackson’s opponents did, and find some issue about which to fear-monger, or to do what Reagan’s opponents did, and remain factionalized. Right now, we seem headed toward the second, and in a somewhat complicated (and genuinely well-intentioned) way.

The advice seems to be that we need to have a unified and coherent policy agenda in order to mobilize voters. And, while I agree that simply being anti-Trump isn’t enough, I don’t think the unified and coherent policy agenda strategy will work either, for several reasons. The first reason is that it is trying to solve the problem of faction through faction. The second (discussed much later) is that it grounded in a misunderstanding of how Americans vote.

3. Trying to solve the problems of factionalized politics by creating a more unified faction

[Most of this section was pulled out and posted separately here.]

4. The mobilizing passion/policy argument

Speaking of reasonable arguments and thinking about probabilities, what are reasonable ways to go on from here and not repeat the errors of the past? The two most common arguments as to what we should do now are both, I’ll argue, reasonable. I’ll also argue that they’re probably wrong. But they aren’t obviously wrong, and I doubt they’re entirely wrong. One is that we’re losing elections because we aren’t putting forward a charismatic enough leader who inspires passionate commitment to a clear identity (what I always think of as “the Mondale problem”). The second is that the problem with the Dems in 2016 is that they didn’t have a sufficiently progressive platform of policies, and so there wasn’t a mobilizing political agenda. Therefore, we should have clearer mobilizing identity or political agenda.

I think these are reasonable arguments, but I don’t think either of them will work—I’m not sure they’re plausible (they certainly aren’t sufficient), and I’ll explain why in reverse order.

First, as to the “we just need someone with a clear progressive policy agenda,” I have to say that a lot of lefties who make that argument in my rhetorical world turn out to have no clue what policies Clinton advocated. They lived in a world of hating on Clinton throughout the election, and so remain actively misinformed about her policy agenda (and the number of them who shared links from fake news sites in October was really depressing).

A lot of lefties are political wonks, and so we assume that everyone else is equally motivated by policy issues. Unhappily, a lot of research suggests that isn’t the case. The next section relies heavily on three books: Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s Stealth Democracy (2002), Achen and Bartels’ Democracy for Realists (2017), and Parker and Barreto’s Change They Can’t Believe In (2014). I should say, before going through the research on the issue, that I’m not as hopeless about the prospects for more policy argumentation in American public discourse as I think these authors are, and I do think that improving our politics through improving our political discourse is the most sensible long-term plan. For the short-term, however, I think it makes sense to be pragmatic about how large numbers of people make decisions about voting, and they don’t do it on the basis of deep considerations of policy—or on the basis of policy at all.

John Hibbing and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse summarize their research: people care more about process than they do about policy, and they “think about process in relatively simple terms: the influence of special interests, the cushy lifestyle of members of Congress, the bickering and selling out on principles” (13). According to Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, people believe that the right course of action on issues is obvious to people of goodwill and common sense who care about “normal” Americans: people believe that there is consensus as far as the big picture and that “a properly functioning government would just select the best way of bringing about these end goals without wasting time and needlessly exposing the people to politics” (133). Hibbing and Theiss-Morse refer to “people’s notion that any specific plan for achieving a desired goal is about as good as any other plan” (224).

A disturbing number of people believe that the correct course of action is obvious, because it looks obviously correct from their particular perspective. And I should emphasize that it isn’t just those stupid people who do it. Even lefties—even academic lefties—who emphasize the importance of perspective, teach about viewpoint epistemology, and reject naïve realism can regularly be heard at faculty meetings bemoaning the benighted administration for its obviously wrong-headed policy. In my experience, there is always a perspective from which the administration’s response is sensible. Most commonly, something that puts a great burden on my department (and my kind of department) is a policy that works tremendously well for most of the university, or for the parts of the university that the administration values more. Sometimes the bad policies are mandated by the state or federal government, or sometimes they are, I think, a misguided attempt to improve the budget situation. From my perspective, their policies look bad; from their perspective, my preferred policy looks bad.

I’m not saying that both policies are equally good, or all perspectives are equally valid, or that there is no way out of the apparent conundrum of a lot of people who all sincerely care for the university disagreeing as to what we should do. I’m saying that it’s a mistake for any of us to think that the correct course of action is obviously right to every reasonable person. I’m saying we really disagree, and that determining the best policy is complicated.

Most important, I’m saying that the tendency to dismiss disagreement and assume that complicated problems have simple solutions is widespread.

Since this depoliticizing of politics is widespread, how do people explain all the disagreement about policies? Hibbing and Theiss-Morse argue that people believe that most politicians are self-interested, and bicker so much because they are submissive to the “special interests” that donate money to them: “The people would most prefer decisions to be made by what [Hibbing and Theiss-Morse] call empathetic, non-self-interested decision-makers” (86). They quote one of the participants in their research who “said he had voted for Ross Perot in 1996 because he felt Perot’s wealth would allow him to be relatively impervious to the money that special interests dangle in front of politicians” (123).

Hibbing and Theiss-Morse are persuasive on the profoundly anti-democratic way that people perceive “special interests.” They say, “Our claim is that the people see special interests as anybody with an interest. Since government is filled with people who have interests, the people naturally come to the conclusion that it is filled with special interests.” (226)

People use the term “special interest,” according to Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, “to refer to anybody discussing an issue about which they do not care” (222).

We see ourselves as “normal” Americans, whose needs should be central to American policy, and whose problems should be solved quickly and sensibly. Were government functioning well, that’s what would happen, but it isn’t happening because the people in office put “special interests” above people like us, so we want someone who conveys compassion and care for us.[5]

That claim—that voters care more about caring and quick solutions to their problems and are neither interested in nor moved by policy deliberation—is supported by Achen and Bartels’ Democracy for Realists, which reviews years of studies in order to refute what they call the “folk theory of democracy.” That theory assumes that democracy is “rule by the people, democracy is unambiguously good, and the only possible cure for the ills of democracy is more democracy” (53).

Achen and Bartels conclude that elections don’t represent some kind of wisdom of the people, but “that election outcomes are mostly just erratic reflections of the current balance of partisan loyalties in a given political system” (16). Achen and Bartels argue that voters’ perceptions of policies—even basic facts—are largely determined by motivated reasoning (people use their powers of reason to rationalize a decision they have made for partisan reasons) or simply out of a desire “to kick the government,” even for natural disasters over which the government had no control (118). People aren’t motivated to join a party because they like the policies: “The primary sources of partisan loyalties and voting behavior, in our account, are social identities, group attachments, and myopic retrospections, not policy preferences or ideological principles” (267). By “myopic retrospections,” they mean events that happened in a very short period just before the election, for which they are punishing the incumbents.

Achen and Bartels refer to Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, and other scholars, in their conclusion that “many citizens in well-functioning democracies” don’t understand the value of opposition parties and the necessary disagreement that comes with different points of view.

They dislike the compromises that result when many different groups are free to propose alternative policies, leaving politicians to adjust their differences. Voters want ‘a real leader, not a politician,’ by which they generally mean that their ideas should be adopted and other people’s opinions disregarded, because views different from their own are obviously self-interested and erroneous. (318)

There is a right way, in other words, and it’s the way that looks right to normal people, and it’s the one that should be followed.

Michele Lamont’s The Dignity of Working Men (2000) emphasizes that many men (especially white) gain dignity from seeing themselves as disciplined, and explain their success as completely their own individual achievement—they actively resent goods (such as support of various kinds) being given to people who don’t work (see especially 132-135; this was less true of African Americans whom Lamont interviewed, who tended to emphasize the “caring” self). And, especially for white men, wealth isn’t necessarily good or bad; they don’t necessarily resent people who are more wealthy, but they do resent people with higher status who look down on them (108-109). They want to feel respected and cared about (which may explain Trump’s success with precisely the kind of voter whom many people thought would resent his problematic record with small businesses).

What all of this means is that thinking that the issue for the Dems in 2016, or the issue at the state and Congressional level, is that we haven’t articulated a compelling and thorough policy argument is almost certainly wrong. People who voted for Obama and then voted for Trump weren’t drawn by his policies, but his identity. As Achen and Bartels remind us, voters often get wrong the policies of their favorite political figures or their own party. And voters are easily maneuvered by mild shifts in wording (asking people about ACA versus asking them about Obamacare, for instance). Large numbers of voters don’t care about policies.

They care about slogans—they care about being told that the party or politician cares about them, and will throw out the bastards, drain the swamp, clean house. Large numbers of people want to be reassured that their needs and desires for themselves are the only ones that matter and will be the first priority of the party/rhetor.

And a lot of voters vote on the basis of promises the candidate can’t possibly fulfill. This isn’t just something that their ignorant supporters do. Certainly, Trump promised to do things the President can’t do without thoroughly violating the Constitution (since he was proposing to dictate Congressional and judicial policies–but both Sanders and Clinton proposed policies there was no reason to think they could get through a GOP Congress. I’m repeatedly surprised at the reactions of large numbers of people to SCOTUS decisions–many people (including smart and sensible friends) don’t seem to understand that it isn’t the job of SCOTUS to make sure that laws are “just”–it’s their job to make sure they’re constitutional.

In the early spring of 2016, I was in a hotel in Louisiana eating the fairly crummy free breakfast, and two men behind me were discussing Trump (they liked him). When they talked about how he was going to do something about all those poor people who lived off of the government, one of them said, “Well, what are you going to do? You can’t kill ‘em.” Then they got onto the subject of his plan for ISIS. One of them said, “They’re complaining that he won’t say what his plan is. But of course he can’t say what it is.” The other said, “Right, then ISIS would know it!” Trump’s promise was to develop a plan to crush and destroy ISIS within 30 days of taking office. His plan, as it turned out, was to tell the Pentagon to come up with a plan—as though that had never occurred to Obama?

What they needed was to believe he was the kind of person who could solve problems. He told them political issues are simple, and he was a straightforward person who, like Perot, couldn’t be bought—he wouldn’t genuinely represent them and their interests. And now he is saying that it turns out every single issue is complicated.

I often wonder about those two guys, and what they make of all this. If research on people drawn to simple solutions is accurate, then they’re doing one of three things: 1) rewriting history, so that they never voted for him on the grounds that he could solve things quickly and easily; 2) making an exception for his finding things complicated, and using his new admission that he was entirely and completely wrong in everything he said about politics as additional evidence of his “authenticity” and sincerity (and, since all they care about is that he sincerely cares about them, they’re good); 3) regretting voting for him, but not rethinking why they voted for him, what their assumptions were about how to think about politics.

That’s what happened with the Iraq invasion, after all. People who had supported it denied they’d ever supported it, denied it was a mistake, or blamed Bush for lying to them. They didn’t decide that their process of making a decision about the war was a mistake—they didn’t stop watching the channels that had worked them into a frenzy about Saddam Hussein’s (non) participation in 9/11 or the (non)existence of weapons of mass destruction. They didn’t stop making political decisions on the basis of hating Dems, or trusting a political figure because he seemed like someone who cared about them.

So, no, we can’t reach that sort of person with a more populist political agenda because it isn’t about the political agenda.

I think it’s also a mistake to think that, since they’re engaged in demagoguery, and it’s winning elections for them, that’s what we should do. Demagoguery, a way of approaching public discourse that makes all political issues a question of us (angels) versus them (devils) works for reactionary politics because reactionary politics is attractive to “people who fear change of any kind—especially if it threaten to undermine their way of life” (Parker and Barreto 6). Reactionary politics, according to Parker and Barreto and also Michael Mann, arises when a group is losing privileges (such as whites losing the privilege of being able to see their group as inherently superior to non-whites). Democrats played that card for years, and it worked, but now it would alienate as many people as it would win (or more). The research on “moral foundations” is pretty clear that, while loyalty to the ingroup is important for people who self-identify as conservative, fairness across groups is important for people who tend to self-identify as liberal. Any rhetoric that says “this group is entitled to more than any other group” will alienate potential liberal voters.

While there is a lot of lefty demagoguery, it’s internally alienating. That is, the presence of internal demagoguery is what makes some people very hesitant to support the Democratic Party. And now we’re back to the two narratives of 2016—both are demagoguery, and both alienate people. We need to imagine a way to move forward that doesn’t involve any one kind of lefty becoming the only legitimate lefty.

And demagoguery won’t get us there.

And that brings us to the second option: find a charismatic leader. That’s a great idea, and we should always hope that our candidates can come across as people who really care about “normal” people (with, I would hope, a broader version of “normal” than reactionary politicians present), but 1) that is only an option if there is a deep bench of Democratic governors and Senators, and 2) that still doesn’t get a reasonable balance in Congress, state legislatures, or among governors.

So, what went wrong in 2016? We had a shallow bench. There are lots of reasons for progressives’ poor showing at the state and Congressional level—low progressive voter turnout in 2010 that enabled gerrymandering, a tendency for progressive voters only to come out for the Presidency, and various other complicated things (including the success of factionalized hate media). What won’t work is something I hear a lot of progressives say: “We just need to run more progressives.” People have been saying that for a long time, and trying it for a long time, and sometimes running progressives works and sometimes it doesn’t, so there is no “just” about it.

The first thing lefty voters need to do is get out the vote at the state level. And I think we need to be very clear that we care about all kinds of voters, and lefty rhetoric about hillbillies and toothless white guys doesn’t help, so we also need to shut down classism as fast as we shut down any other kind of bigotry.

And we can’t win within the parameters of demagoguery, so we need to stop trying to play within them.

5. On the Democratic Party as a strategic coalition

At the beginning, I talked about my initial perception of politics as a contest between what is obviously the right course of action and various things that other people want—because they’re selfish, wrong-headed, corrupt, misguided. Compromise made a good thing worse because it was a question of how much bad had to be accepted in order to get some good done, and it should only be done for Machiavellian purposes. I think too many lefties operate within that model.

When the refusal to compromise goes wrong, it ends up landing people in purity wars, and those are never good for people who are trying argue in favor of diversity and fairness. Purity wars can work well for authoritarians, racists, and people with what social psychologists call a “social dominance orientation,” but they don’t work well for the left.

So, simply refusing to compromise isn’t going to ensure better policies; it can ensure worse ones if, as happened under Reagan (or in Weimar Germany in 1932), the refusal to compromise means that the left is entirely excluded. Saying that refusing to compromise can be harmful isn’t to say that all compromises are good. I’m saying compromise isn’t necessarily and always good, but neither is it necessarily and always wrong. I’m saying that we should stop assuming it’s always evil, and we should stop falsely narrating effective lefty leaders as people who refused to compromise—they compromised. In fact, every effective leader on the left was excoriated in their time for having compromised too much.

The refusal to compromise comes from thinking about politics as a negotiating between right and wrong. We might instead think of politics 1) as the consequence of deliberation, not bargaining, 2) as an acknowledgement of the limitations of our own perspective, and/or 3) as a sharing of power with those people who share our goals. I think lefties would do well to think of at least some compromises as coming out of one of those three factors.

Here’s what I now think: thinking about compromise as always and necessarily wrong is bad, but neither is every compromise right. There are times when you say there is some shit you will not eat, and I am known as a difficult woman because I have refused to go along with various motions, statements, policies, and actions. I have nailed more than a few theses to a door. But I think lefties’ failure to think about compromise as anything other than distasteful realpolitik comes from, oddly enough, a less than useful way of thinking about diversity.

I think too often lefties accept the normal political discourse of thinking in terms of identity (even though we, of all people, should understand that intersectionality means that there aren’t necessary connections between a person and their politics), so we imagine that we have achieved diversity when we have a party that looks diverse—as though that’s all the diversity we need. So, we aspire to a political party that is diverse in terms of identity and univocal in terms of policy agenda. And I don’t think that’s going to work.

Instead of striving for a group that is univocal in terms of policy but diverse in terms of bodies, we need to imagine a party that is diverse in terms of what the Quakers call “concern.”

Early in the history of the Society of Friends, meetings struggled with what we would now recognize as burnout—people at meetings would speak of the need for everyone to be concerned about this and that issue, and everyone couldn’t be concerned about everything. So, there arose the notion that the Light makes itself known in different people in different ways, and that each person has a concern which is not shared with everyone. I think that’s what we on the left should do—we should be people concerned with inclusion, fairness, and reparative justice, and who are open to different visions of how those goals might manifest in moments of concern (and policy).

There are, of course, problems with calling for more diversity of ideology on the Left, including that it means cooperating with people whose views we think wrong. And so we have to figure out how much wrong we’re willing to allow. LBJ allowed Great Society money to go to corrupt Democratic machines, believing it was a necessary first step; Margaret Sanger cooperated with eugenicists, since it got her money and support; FDR compromised with segregationists in regard to the US military; Lincoln was willing to talk like a colonizationist to get elected and compromised with racists about pay for black troops. I don’t think they should have made those compromises.

There are some compromises that shouldn’t be made, and so we shouldn’t—but we should argue about what those limits are. And there may be times that we decide to compromise on purely Machiavellian grounds; I’m not ruling that out. But I am saying that lefties shouldn’t treat every disagreement as something that must be resolved with pure agreement on the outcome—that’s just a fear of difference. Lefties disagree. We really, really, really disagree. Lefties need to imagine that disagreement is useful, productive, and doesn’t always need to be resolved. We need to imagine a politics in which each of us gets something important for our well-being and none of us gets everything. And we need to stop hoping and working for a party of purity.

[1] If it helps one side too much, of course, then both end up losing—if interest rates are too high, no one takes out loans, and then lenders are hurt; or high interest rates might tank the economy, which can make it hard for lenders to find money to loan.

[2] It’s generally done through division—you and I are alike because we both hate them. Salespeople will often do it on big ticket sales, and con artists always use it.

[3] One sign of how factionalized a situation is is how often when I’m talking about this I have to keep saying that not all Sanders supporters are Sandersistas and not all Clinton supporters are Clintonistas. As scholars of group identity say, the more that membership in a group is important to you, the more that any criticism of any member of that group will feel like a personal attack.

[4] One of the odder arguments I sometimes hear people make is that Clinton was at fault for not motivating them—it’s the Presidency, not a hamburger; you’re responsible for making choices, and not a passive consumer of marketing. (Talk about a neoliberal model of democracy.) That argument irritates me so much I won’t even list it as a reason.

[5] While Hibbing and Theiss-Morse maintain this is not authoritarianism, because people want a direct connection to the halls of power when the government is not being appropriately responsive, I would argue that neither is it democratic (little d) in that there is no value given to deliberation or difference. And, of course, it’s how authoritarian governments arise—people give over all their power of deliberation to someone who will do it for them. When they want it back, they can’t always have it.

That chain of paired terms is what enables Hitler to get to what is actually an amazing argument for a purportedly Christian nation: that valuing fairness across groups is suicide, and part of a plot to weaken Germany.

That chain of paired terms is what enables Hitler to get to what is actually an amazing argument for a purportedly Christian nation: that valuing fairness across groups is suicide, and part of a plot to weaken Germany.