My first publication was in The Nation Weekly (a journal that briefly existed in the 70s), and the second was in a collection about Writing Centers. Both of those were things I happened to write for various reasons that someone else wanted to publish for their own reasons. In graduate school, a colleague wanted to publish a special issue about reading, and I was working on how John Muir read the landscape, and so that happened.

I then entered into years of hostile readers, bad choices about where to submit, misunderstandings about the genres of academic writing, and a failure to seek out better advice. (That’s kind of funny if you think about it—I was failing to try to figure out my rhetorical situation.)

It was clear from my dissertation work that John Muir’s inability to persuade conservationists to preserve the Hetch Hetchy Valley when he had previously been so successful was the consequence of the intellectual milieu changing—from Romanticism (dominant when he was first writing) to a kind of proto-third-way-neoliberalism (the best use of public resources is the one that advances market interests while remaining in public ownership). It was also clear to me that there was a hermeneutic and epistemological issue at play: people disagree(d) about what to do in regard to the environment because they disagree(d) about what the natural environment means—how to read it. And people disagree because of questions of how to know what we read: are our value judgments in the environment or in our minds? (This is valuable regardless of whether people value it, or this is valuable to the extent that people value it.) Everyone was reading Nature as though it were a book, but they brought different notions of how to read, and that’s why they disagreed about what to do.

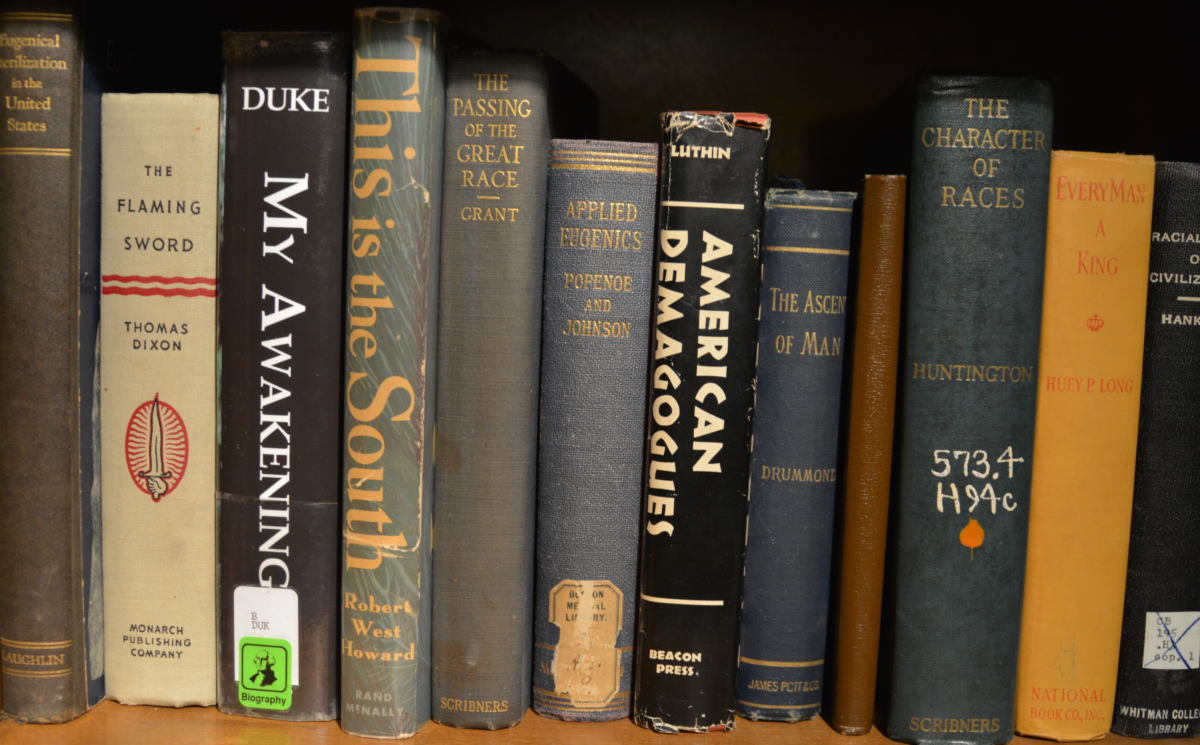

There was another interesting glitch, that I couldn’t quite process. There were, as I was writing my dissertation, major scholars who argued that you could dismiss environmental concerns on the grounds that the kind of people who had those concerns were irrational.

So, I thought, my first book should trace out the connections I suspected were there: attitudes toward nature, epistemologies, and hermeneutics, and somehow it would end up on that point about dismissing arguments on the basis of motivism. It would move from the American Puritans up to Muir and the Hetch Hetchy Valley debate.

Looking back on this, I came to see that graduate school sets people up for the mistake I was making. In graduate school, you read the most famous scholars’ most recent work (except in the case of teacher who wants to trash another school of thought or scholar, in which case you read their early work, and spend a class talking about how simplistic and jejeune their article is). Scholars, toward the end of their careers, write in a completely different way from people early on—they can engage in grand narratives, broad brushes, and assertions that come from having thought about something for thirty years. We try to write what we read, and so junior scholars are set up for failure by trying to write in the way that an established scholar can write—the rules are different.

Eventually, I tried to write a book that started and ended with John Muir, but was almost entirely about the American Puritans. (A university press was interested, and kept telling me they would let me know—their editor was ill. There were many emails about how they would let me know in three weeks as the tenure clock was in the final seconds and a dean was telling the department not to support me. I have literally never heard a final word from them. They were discontinued. I was denied tenure. I got a better job.) I also directed a first-year comp program and pissed off a dean. I tried to publish an article about Horatio Alger, and another about Robert Montgomery Bird, and both were stymied.

I moved to a department that had more people publishing in the history of rhetoric, and those faculty gave me really useful readings of my manuscript, and I connected with a better press, and I got a book manuscript accepted, and then I published pieces from it (not the normal chain of events).

That book was about the 17th century New England Puritans, and how their notions of rhetoric, epistemology, and public deliberation did and didn’t fit together. No one in rhetoric and writing had written on the Puritans for a long time, and so I couldn’t make the normal scholarly moves of “They say but I say.” There was no current “I say.” Also, it irritated me off that one part of my argument was that we got the transmission model (the thesis-first) from the Puritans, and it came from their belief that persuasion doesn’t really happen. You tell people the truth, and they recognize it. Good people act on that truth, and bad people dismiss it (a model of persuasion oddly persistent even in current studies). One of the reviewers (a comm and not comp person) insisted I put my thesis first. I grumped about it.

I intended that book to be the first part of a series, so that the next book would be looking at the rhetorical theories, epistemologies, hermeneutics, and attitudes toward nature in the late 17th and early 18th century American culture. I read a lot of 19th century American popular literature, but I couldn’t write that book. The erasure, dismissal, rationalization, and rhetorical shittiness about the indigenous peoples was too awful for me to manage. For instance, I had an article about Robert Montgomery Bird and the paradox that the same actions were to be condemned when done by Native Americans but considered heroic when done by “whites” (aka, why I can’t watch most movies). One reader said, and I’m not kidding, “But don’t you think they deserved it?” I put that and the Horatio Alger article away.

grrrrr

I have been a fan-girl of Hannah Arendt since junior high school when I read Eichmann in Jerusalem. In graduate school, for reasons even now I can’t determine, I ran into a Habermas article with an amazing endnote about how rhetoric (bad) and communicative action (good) interact. He cited speech act theory, so I took a class with John Searle (I think I got a B+, and I still really appreciate that class). As a Comp Director, I found myself in a lot of uselessly non-arguments about argumentation—people opposed teaching argumentation because they believed that no one is ever persuaded of anything (they taught the 5 paragraph essay, and they had noticed that that genre is unpersuasive, and so concluded persuasion is impossible). Their perception of persuasion is that a person has the truth, and tells it to another (the recipient) and then that person has the truth. If the recipient doesn’t have the truth at the end, then it’s proof that persuasion isn’t possible. (You hear both of those arguments a lot still.)

That’s an obviously silly model of persuasion, but, oddly enough, it’s dominant, and not restricted to one political group or philosophical approach. You can hear poststructuralists, neoconservatives, neopositivists, and behavioralists all cite studies that show no one is actually persuaded by evidence, and cite studies to support their position. (I think that’s funny.) Wayne Booth and Jurgen Habermas both nailed this one, showing that a lot of people toggle between two models of persuasion (neither of which is the one on which they actually operate): they toggle between the notion that you are persuaded by unemotional logic or you are persuaded by emotion. Oddly enough, the people arguing for it’s all emotion cite scientific studies to support their point. If they really believed it’s all emotion, they wouldn’t cite studies; they would just assert their point. Their engaging in argumentation shows that they think argumentation does potentially have an impact. This is sometimes called the pragmatic contradiction.

This problem (people engaged in persuasion who insist that no one is ever persuaded) starts from asking the wrong methodological question. You have a person who believes s/he has the truth (the experimenter) and s/he asks the experimentee what s/he believes, then presents an assertion that the experimentee is wrong. The experimentee doesn’t immediately convert on the basis of this short interaction, and the experimenter concludes that persuasion doesn’t happen! The experimenter has given the experimentee objective evidence (rational) that the experimentee doesn’t instantly accept, so the experimentee is irrational.

The irrational (no logic, all emotion)/ rational (no emotion) split is like dividing everything into round or green. Some people (roundists) are very narrow in their definition of what is round, and they declare everything that doesn’t fit that narrow definition as green. Therefore, skyscrapers are green. The greenists are very narrow about what is green, and call everything else round.

This might seem like a silly example, but it’s how American media presents politics. Major televisions media accept the Us or Them binary and then find all sorts of reasons at this or that moment to draw the lines differently. Unhappily, too many Christians do the same, accepting the premise that all the various positions can be divided into two, and then you argue about where the Us v. Them line is drawn. Given Christ’s message, we really should know better.

In any case, my point is that believing that squirrels are evil beings trying to get to the red ball is rational, and truly patriotic, means that you will perceive anyone who disagrees with you on that point as irrational and unpatriotic. And I saw that how “argumentation” was (and is) taught would reinforce that foundational fallacy.

I was convinced that the hostility to teaching argumentation in first year composition came from two places: 1) different conceptions of what it means to participate in democracy; 2) the rational/irrational split. So, I thought, I would write a book that would show the connections between models of democracy and pedagogies and that would end more hopefully and pragmatically, with a long discussion about what advances in argumentation meant for the teaching of argument.

So, what became Deliberate Conflict was supposed to be about half of a book. I wrote that book, and then farmed out parts (that isn’t how you’re supposed to do it) and it was too long. I had to take my favorite part (about Arendt) and put some of it into an article.

I had a bit of a glitch with moving (having been given tenure) to a new place and with certain promises being given that were cheerfully reneged, and so had to write two books to get associate professor and three for full. (And, yes, I’m bitter about that, since the two people who made that happen have never apologized or even acknowledged that their regneging might have caused me some grief. One of them has twice told me it was no big deal.)

Here things get complicated, since I was given my first paid leave in my career. I got my degree in 1987, and it was 2003 (or 4—I’m vague on that). I had been directing a very large first year composition program at my first job, and a slightly smaller one at my second. I HAD A LEAVE. I sent out a bunch of articles.

One of the articles I sent out in 2003 or 4 was the one a colleague (in 1992 or so) had told me was unpublishable because my argument about how whites justified pre-emptive violence against indigenous people “ignored that they started it,” and it got an award. The best vengeance is success.

I had long since moved on to the argument that agonistic rhetoric was the bomb, and the post-bellum shift away from agonism was bad. And a graduate student asked me, “If antebellum methods of teaching rhetoric were so good, why couldn’t we solve the slavery problem rhetorically?” So, I set out to write a book about the slavery debate. It was an elegant plan for a book, with five chapters: the public pro-slavery; the counter-public pro-slavery (since I wanted to undermine the public/counter-public binary which is often a good/bad or bad/good binary), the public pro-slavery, the counter-public anti-slavery, the public pro-slavery, and the mediators (that no one talks about anymore, but were once the heroes: Webster, Clay, Calhoun).

It ended up being a book about the proslavery argument between 1830 and 1835. (In other words, every book I’ve written has started out as a much longer book.)

The Civil War didn’t happen because both sides were fanatics, nor because they couldn’t compromise. The Civil War happened because the Constitution gave an advantage to slave states, slavery became the single identifying sign of Southernness, and fanaticism on behalf of slavery was a sure path to political success in a slave state. The Civil War happened because, having won every “compromise” in regard to slavery (that is, the US was becoming increasingly a slave nation) the slave states saw a political opportunity when Lincoln was elected. Their extremist rhetoric got them extremist politics and a war they never needed to have.

They thought they needed the war because they lived in an informational enclave in which various events (e.g., the mass mailing of AAS pamphlets) were a fact, although they didn’t actually happen (there was no flooding of the South with those pamphlets). They also lived in a culture in which it was dishonorable to argue pragmatically about various outcomes, including failure, and so it was the classic situation of amplification.

I was working on this book in 2003, and I thought the Iraq War was the same situation. It was a war that never needed to happen, and it happened because large numbers of people believed things that were false (Saddam Hussein was behind 9/11 and he had WMD), but they lived in a world in which those myths were foundational facts.

That seemed to me demagoguery. And, so, I got interested in demagoguery. And I read everything recent about demagoguery (there was not much in rhetoric and writing) and wrote an article arguing that rhetoric should pay attention to demagoguery. And the responses are there to read. I ran into a really kind and smart person at an airport who asked if I was going to respond to them, and I said no. I wanted to get the argument going, and I thought I had, and I also thought that responding to those articles would have involved my saying, “Yeah, I’m just gonna repeat what I said, since y’all obviously didn’t read the article I wrote, and just responded to something in your heads.”

I never said demagoguery was about emotionalism, for instance. Sheefuckingeesh.

And then I started working hard on a book about demagoguery. And it was going gangbusters, and it’s a weird book, and it was sent to readers, one of whom said demagoguery was a dead issue.

The book is a point by point refutation of common notions about demagoguery. Demagoguery isn’t just about the demes, it isn’t necessarily emotional, it has a weird relationship to expert discourse. I deliberately chose to have a section on a person I admire. And it has a chapter in which my point is that rhetoric can enable someone to identify shitty expertise discourse. But it’s a weird book, inductively argued.

In any case, my point in all of this is that a scholarly trajectory isn’t something you direct from the beginning. Trajectory is, I’d say, entirely the wrong metaphor. It’s more like following scat. You have something you’re hunting, and you follow the scat of the thing you’re hunting. I’ve had a lot of setbacks—a press that was uncommunicative and then went under, a dean out to make sure I was denied tenure, people in power who cheerfully reneged on promises, unsympathetic reviewers. But I’ve also had a lot of good breaks, reviewers who saw promise, editors who turned hostile reviews into a forum, hitting the job market at good moments, supportive colleagues and challenging students.

Nicholas Taleb has an analogy I think is really helpful. He says that you should imagine a study in which a thousand people are asked to engage in Russian roulette. After five shots, there will be some people standing. He points out that those people will be asked about their strategies, and whatever those people say they did will become the mantras for success in…. in his case, it’s finance.

There are no strategies that will guarantee success in our field. There are some really good books out there about what are strategies you can try, but there’s no guarantee.

You do any job for love or money. No one does academia for money, so it had better be for love. And what is it you love? When I started teaching, it was for love of teaching, but promotion required publication, and I came to love research. (I still don’t love publishing.) And this Robinson Jeffers poem has always moved me:

“I hate my verses, every line, every word.

Oh pale and brittle pencils ever to try

One grass-blade’s curve, or the throat of one bird

That clings to twig, ruffled against white sky.

Oh cracked and twilight mirrors ever to catch

One color, one glinting

Hash, of the splendor of things.

Unlucky hunter, Oh bullets of wax,

The lion beauty, the wild-swan wings, the storm of the wings.”

–This wild swan of a world is no hunter’s game.

Better bullets than yours would miss the white breast

Better mirrors than yours would crack in the flame.

Does it matter whether you hate your . . . self?

At least Love your eyes that can see, your mind that can

Hear the music, the thunder of the wings. Love the wild swan.

He’s referring, of course, to Yeats’ “Wild Swans” poem, and his own sense that he could never be Yeats. And, initially, he’s seeing writing as nailing down the thing about which he’s trying to write (note my own “nailing” metaphor above). But we will never nail to the wall anything about which it’s worth writing. We need to love what we’re trying to write about. We need to love the thing we’re chasing. It isn’t about shooting something; it’s about following a trail. I generally hate my writing, and find the slippage between what I say and what I’m trying to say sometimes incredibly discouraging. But I love democracy, and I try to make that good enough.

For years, I’ve had this quote in my signature: “You ain’t got nuthin’ to do but count it off.” And every once in a while someone asks me why. It isn’t a command to others, or even a pithy statement everyone should know; it’s a reminder to me.

For years, I’ve had this quote in my signature: “You ain’t got nuthin’ to do but count it off.” And every once in a while someone asks me why. It isn’t a command to others, or even a pithy statement everyone should know; it’s a reminder to me.