This was going to be one post, but it turned into several. And it’s a set of posts, not about how appeasing Hitler was right (it wasn’t), but about how people like us actively supported Hitler, or actively supported appeasing him.

It’s common for people to express outraged bewilderment at British politicians and figures who appeased Hitler—we claim not to understand how they could have been duped by him, how they could not have seen him for who he really was. We like to explain appeasement either by saying that Hitler was a rhetorical magician, whose persuasive skills were overwhelming, or by saying that the people who didn’t take him seriously enough were fools engaged in wishful thinking. Neither is the case. In fact, many of us would have supported appeasing Hitler. If we try to tell a story of an irresistible rhetor or hopelessly gullible political leaders, then we are the gullible ones.

In other words, this isn’t about Hitler, and it isn’t about Chamberlain. It’s about us.

Hitler, like many manipulative people, didn’t persuade others, as much as he gave them the tools that enabled them to persuade themselves of something they already wanted to believe. Those strategies (and those people) allowed Hitler to normalize Nazi behavior and deflect his personal responsibility for what couldn’t be normalized.

On May 11, 1933, the British Ambassador to Germany, Horace Rumbold, met with Hitler. Hitler had only been in the government since that January, and dictator since that March, but Rumbold already had him correctly sized up. Rumbold described the meeting in a dispatch back to the Foreign Office (Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939, Second Series, Volume V #139) and his description of it shows how Hitler’s rhetoric worked (and, in this case, didn’t work) and with whom.

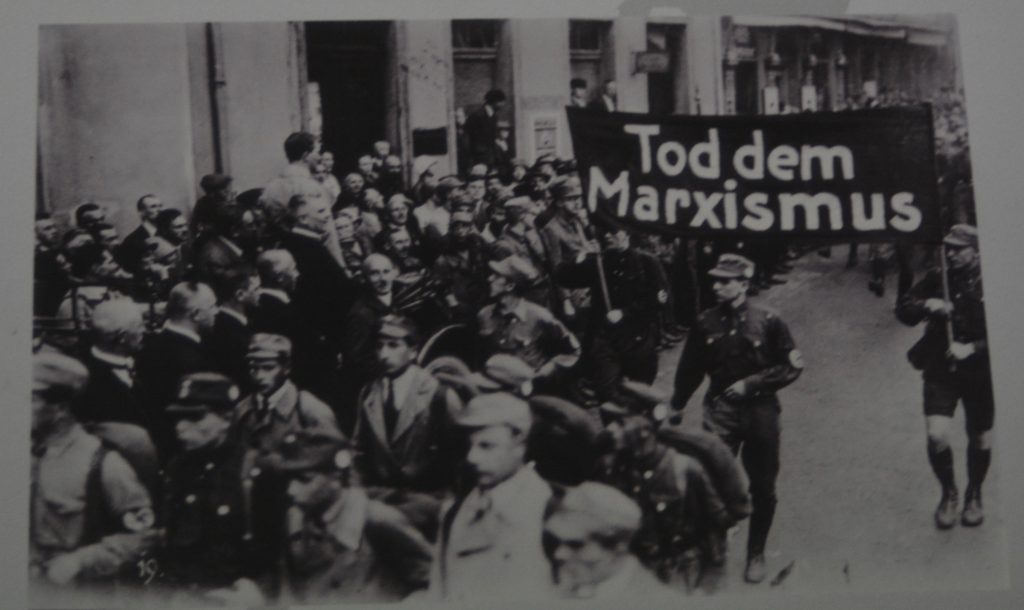

The meeting was fairly typical of meetings with Hitler—he did most of the talking, got unhinged on the subject of Jews, deflected (especially through whaddaboutism), and lied or exaggerated when he couldn’t deflect. After the Reichstag Fire, the Nazi government arrested anyone considered communist, a category that included labor union activists. Nazi persecution of Jews was well known, as well as violence against communists.

Because he had read Mein Kampf and been listening to speeches by Hitler and other major Nazis, Rumbold knew exactly what Hitler planned. In a memo written not long before this meeting (Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1939, Second Series, Volume V #36), Rumbold had summarized Hitler’s philosophy (long quotes from Rumbold are the full paragraphs in italics):

He starts with the assertion that man is a fighting animal: therefore the nation is, he concludes, a fighting unit, being a community of fighters. Any living organism which ceases to fight for its existence is, he asserts, doomed to extinction. A country or a race which ceases to fight is equally doomed. The fighting capacity of a race depends on its purity. Hence the necessity for ridding it of foreign impurities. The Jewish race, owing to its universality, is of necessity pacificist and internationalist. Pacificism is the deadliest sin, for pacificism means the surrender of the race in the fight for existence [….] The race must fight: a race that rests must rust and perish. The German race, had it been united in time, would now be master of the globe today. The new Reich must gather within its folds all the scattered German elements in Europe [….] The ultimate aim of education is to produce a German who can be converted with the minimum of training into a soldier [….] Again and again he proclaims that fanatical conviction and uncompromising resolution are indispensable qualities in a leader [….] Germany needs peace until she has recovered such strength that no country can challenge her without serious and irksome preparations.

He was right, as we know. It’s important to point out that his correct interpretation of Hitler and the Nazis was grounded in evidence available to anyone fluent in German—the public and published statements of Hitler and the Nazis. It’s also important to point out that, while Hitler had very recently (around 1932) begun talking in terms of self-determination rather than conquest, shifted to dog whistles about his racist policies, and took to lying about violations of the Versailles Treaty, he never retracted, apologized for, or even qualified his previous very clear statements about German hegemony, the desire for a pure and militarized Germany, the need for violence, the equation of Jews and communism, and so on.

People do change their minds, of course, and so the notion that Hitler wasn’t the hothead he had been in the twenties isn’t obviously wrong. But he only stopped making all those arguments two or three years before becoming Chancellor, and he never retracted them. When people change their minds, they openly retract what they previous said. He changed his rhetoric, and not his mind. He didn’t change his rhetoric because he wanted to hold on to the base he’d created with his militaristic and racist rhetoric; he’d risk losing them if he retracted those sorts of statements. When a political figure suddenly changes their rhetoric, then we have to figure out which sets of statements s/he meant, and one relatively straightforward one is: they believe the one they’ve never retracted, even if they’re stopped saying it or are saying the opposite.

But, back to Rumbold’s despatch about the May 11 meeting.

Rumbold says that Hitler complained about the “Polish Corridor:”

He only wished that the Corridor had been created far more to the east. (This is the same remark as that which he recently made to the Polish Minister). The result of the creation of the Corridor had been to provoke grave dissatisfaction in Germany and apprehension in Poland, for the Poles realized that it was an artificial creation. Thus a state of unrest was kept alive.

So, what is Hitler doing?

First, he wasn’t a mastermind of rhetoric. Someone genuinely skilled in rhetoric wouldn’t harangue people in small meetings, but he was notorious for that—not only for, as he does in this meeting, doing almost all the talking, but actually slipping into giving a speech. He was highly skilled at one kind of rhetoric—he was good at making a speech that moved a crowd. Even William Shirer, the Berlin correspondent for American media, says that he sometimes found himself temporarily moved by Hitler’s speeches, and he knew exactly who Hitler was and what he wanted. Paradoxically (given what we know about Hitler), what came across so effectively in the big public speeches was that Hitler was completely, passionately, authentically, and even irrationally committed to the cause of Germany (the in-group). We don’t expect rational discussions of policy options in large public speeches (although maybe we should); we are particularly prone to the rush of the charismatic leadership relationship. And that’s what Hitler offered.

In one-on-one situations, charismatic leadership works less well—that Hitler was irrationally committed to the cause of Germans wasn’t especially interesting to the British Ambassador. What does work, but only for people who are looking to be persuaded, are the strategies that Hitler uses: projection, whaddaboutism, lying, exaggeration.

Take, for instance, Hitler’s comments about the “Polish Corridor.” The idea that there are “natural” boundaries, which the Polish Corridor violated, is part of Hitler’s racist notions about some “races” being entitled to territory. Of course the boundaries are artificial—that is, made by humans—because that’s what boundaries always are. Poles weren’t worried about the boundaries being artificial; they were worried about German aggression. Hitler’s passive—a state of unrest was kept alive—makes it seem as though Poles were partially responsible for the state of unrest. Were the Poles completely confident about the borders, there would still be a state of unrest because of Hitler’s rhetoric about German entitlement. Poles weren’t apprehensive about the boundaries; they were apprehensive about Nazi aggression. Hitler projects his unrest he creates onto the Poles.

This strategy would work with an interlocutor who believed that states have “natural” boundaries, or that the boundaries set by the negotiations at the end of the Great War were artificial or unfair to Germany. This way of presenting the situation would also work with someone who didn’t really believe that Poles were people who should be considered, or at least not considered as having the same natural rights to self-determination and a nation-state as, say, Germans.

What many people now forget is that the Austro-Hungarian Empire had collapsed with the Great War, and one consequence was the rebirth (or creation, depending on your narrative of history) of various nation-states that hadn’t existed for several lifetimes. Poland and Czechoslovakia were two of those nation-states. Given the vexed and sometimes violent history of 19th century conflicts over nationalism, language, and oppression, some boundaries had been deliberately designed to keep Germans a minority. Were he talking to the kind of racist who believed that Germans were better people than Slavs, Hitler’s implicit argument about the boundaries would seem reasonable. As it happens, he wasn’t at that moment, but he often was. So, one reason that major political figures argued for appeasing Hitler was that they agreed with him that Germans should be politically dominant in central Europe because Slavs were, you know, so Slavic. They would, therefore, overlook that a state of unrest was kept alive because of German leaders like Hitler, and instead be willing to see the situation—self-determination for Slavs designed to keep a minority German population from dominating—as artificial, with some vague sort of “both sides are at fault” way of framing the situation.

These people wouldn’t necessarily think Germany should take over all the areas previously controlled by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but they would be sympathetic to Germany calling a situation artificial if it kept German speakers from political domination. They might object to Germany dominating Europe, but not what they (wrongly) imagined to be racial Germans dominating the political situations in most Central and Eastern European countries.

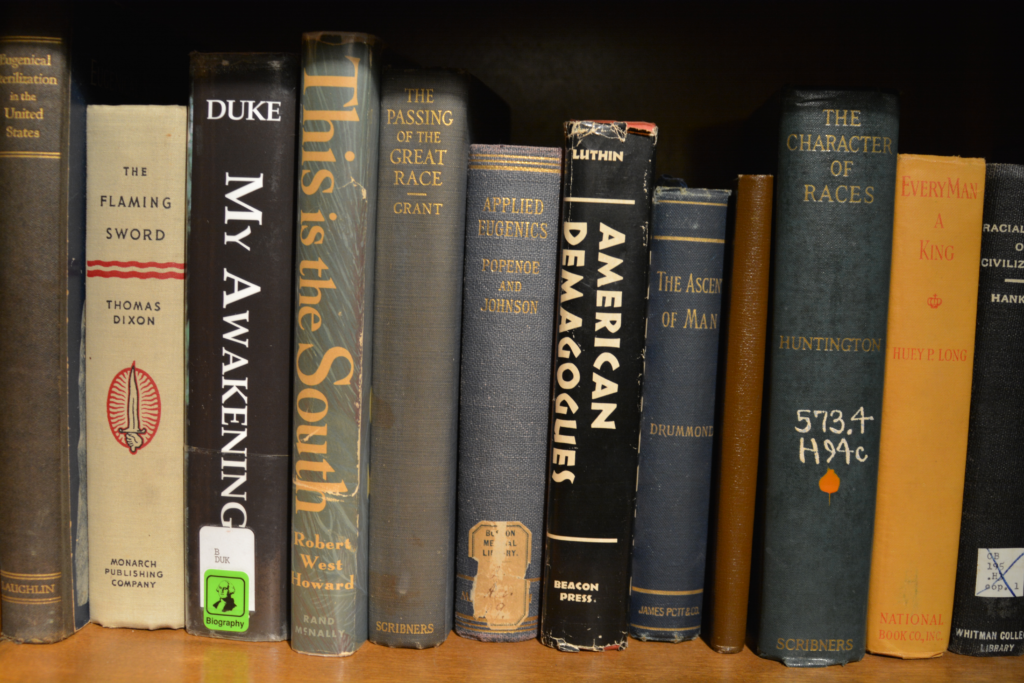

We now forget (or don’t know) how widespread what we now know are bullshit narratives about “race” were in that era. Race, which even the most respected and cited scholarship on race couldn’t define consistently, was incoherently associated with language, and sometimes phenotype (but only when that was politically useful). Books like Passing of the Great Race (1916) or The Rising Tide of Color (1921) were tremendously popular in the US and Britain, and they were pearl-clutching jeremiads about the danger to civilization from Central and Eastern Europeans—that is, from Slavs and, worst of all, Slavish Jews. That was the whole point of the extremely restrictive 1924 Immigration Act—it was designed to reduce the number of people coming from Southern, Central, and Eastern Europe.

Hitler’s griping about the “artificiality” of the Polish Corridor was grounded in the belief that people who self-identified as German (what he would have called “Aryans”) should not be politically dominated by Slavs. And that argument would work with anyone who agreed with the unhappily common premise that politics should not be people from different groups arguing from their different perspectives, but people who have the right point of view being dominant.

So, for our fantasy that we would never have supported Hitler, the important question is: do we believe that ideal political deliberation has people with radically different points of view, people we really dislike and look down on, arguing with one another, or do we think it consists of our in-group being “naturally” (ontologically) entitled to political domination?

If the latter, then we would have loved Hitler, as long as we agreed with him as to what in-group was entitled to political domination.

Just in case I’ve been unclear: if we condemn Hitler, but believe that only our group has a legitimate political stance, and that our group is entitled to domination, then we don’t really condemn Hitler. We would have been open to persuasion to his narrative about the victimization of Germans, since we believe that a group can be victimized simply on the grounds that it isn’t as dominant as it feels entitled to be.

One of the reasons that people supported Hitler–including people shocked that he did what he’d said he would do were he in power–was that they agreed with his premise that there is an in-group that should have all the political power. If we agree with that premise, but disagree as to which group it is, we’re close enough to Hitler that we’re just splitting some very fine hairs.