I mentioned elsewhere that people have a lot of different ideas about what we’re trying to do when we’re disagreeing with someone—trying to learn from them, trying to come to a mutually satisfying agreement, find out the truth through disagreement, have a fun time arguing, and various other options. There are circumstances in which all of these (and many others) are great choices—I think it’s an impoverishment of our understanding of discourse to say that only one of those approaches is the right one under all circumstances.

We also inhibit our ability to use rhetoric to deliberate when we assume that only one approach is right.

I’ll explain this point with two extremes.

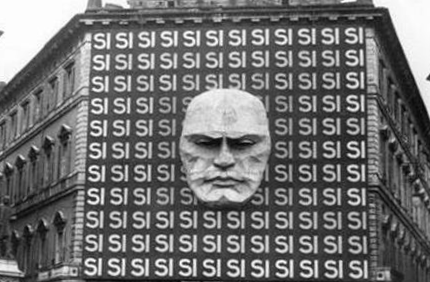

At one extreme is the model of discourse that has been called “the salesman’s stance,” the “compliance-gaining” model, rhetorical Machiavellianism, and various other terms. This model says that you are right, and your only goal in discourse is to get others to adopt your position, and any means is justified. So, if I’m trying to convert you to a position I believe is right, then all methods of tricking or even forcing you to agree with me are morally good or morally neutral.

From within this model, we assess the effectiveness of a rhetoric purely on the basis of whether it gains compliance. For instance, in an article about lying, Matthew Hutson ends with advice from someone who has studied that lying to yourself makes you a more persuasive liar.

“Von Hippel offers two pieces of wisdom regarding self-deception: “My Machiavellian advice is this is a tool that works,” he says. “If you need to convince somebody of something, if your career or social success depends on persuasion, then the first person who needs to be [convinced] is yourself.””

The problem with this model is clear in that example: if you’re wrong, then you aren’t going to hear about it. Alison Green, on her blog askamanager.org, talks about the assumption that a lot of people make about resumes, cover letters, and interviews—that you are selling yourself. People often approach a job search with exactly the approach that Von Hippel (and by implication, Hutson) recommend: going into the process willing to say or do whatever is necessary for you to get the job, being confident that you’ll get the job, lying about whether you have the required skills or experience (and persuading yourself you do).

Green says,

“The stress of job searching – and the financial anxieties that often accompany it – can lead a lot of people to get so focused on impressing their interviewer sthat they forget to use the time to find out if the job is right for them. If you get so focused on wanting a job offer at the end of the process, you’ll neglect to focus on determining if this is even a job you want and would be good at, which is how people end up in jobs that they’re miserable in or even get fired from.

And counterintuitively, you’ll actually be less impressive if it’s clear that you’re trying to sell yourself for the job. Most interviewers will find you a much more appealing candidate if you show that you’re gathering your own information about the job and thinking rigorously about whether it’s the right match or not.”

Van Hippel’s advice comes from a position of assuming that the liar is trying to get something from the other (compliance), and so only needs to listen enough to achieve that goal. The goal (get the person to give you a job, buy your product, go on a date) is determined prior to the conversation. Green’s advice comes from the position of assuming the a job interview is mutually informative, a situation in which all parties are trying to determine the best course of action.

If we’re trying to make a decision, then I need to hear what other people have to say, I need to be aware of the problems with my own argument, I need to be honest with myself at least and ideally with others. (If I’m trying to deliberate with people who aren’t arguing in good faith, and the stakes are high, then I can imagine using some somewhat Machiavellian approaches, but I need to be honest with myself in case they’re right in important ways.)

At the other extreme, there are people who argue that every conversation should come from a place of kindness, compassion, and gentleness. We shouldn’t directly contradict the other person, but try to empathize, even if we disagree completely. We should use no harsh words (including “but”). We might, kindly and gently, present our experience as a counterpoint. Learning how to have that kind of conversation is life-changing, and it is a great way to work through conflicts under some circumstances.

It (like many other models of disagreement) works on the conviviality model of democratic engagement: if we like each other, everything will be okay. As long as we care for one another, our policies cannot go so far wrong. And there’s something to that. I often praise projects like Hands Across the Hills or Divided We Fall that work on that model—our political discourse would be better if we understood that not all people who disagree with us are spit from the bowels of Satan. The problem is that some of them are.

That sort of project does important work in undermining the notion that our current political situation is a war of extermination between two groups because it reduces the dehumanization of the opposition. I think those sorts of projects should be encouraged and nurtured because they show how much the creation of community can dial down the fear-mongering about the other.

They are models for how genuinely patriotic leaders and media should treat politics—by continually emphasizing that disagreement is legitimate, that we are all Americans, that we should care for one another. But that approach to politics isn’t profitable for media to promote, and therefore isn’t a savvy choice for people who want to get a lot of attention from the media.

It also isn’t a great model for when a group is actually existentially threatened (as opposed to being worked into a panic by media). This model says, if we apply it to all situations, that, if I think genocide is wrong, and you think it’s right, I should try to empathize with you, find common ground, show my compassion for you. And somehow that will make you not support a genocidal set of policies? I do think that a lot of persuasion happens person to person, when it’s also face to face. I’ve seen people change their minds about whether LGBQT merit equal treatment by learning that someone they loved would be hurt by the policies they were advocating. I’ve also seen people not change their minds on those grounds. Derek Black described a long period of individuals being kind to him as part of his getting away from his father’s white supremacist belief system, but the guy went to New College; he was open to persuasion.

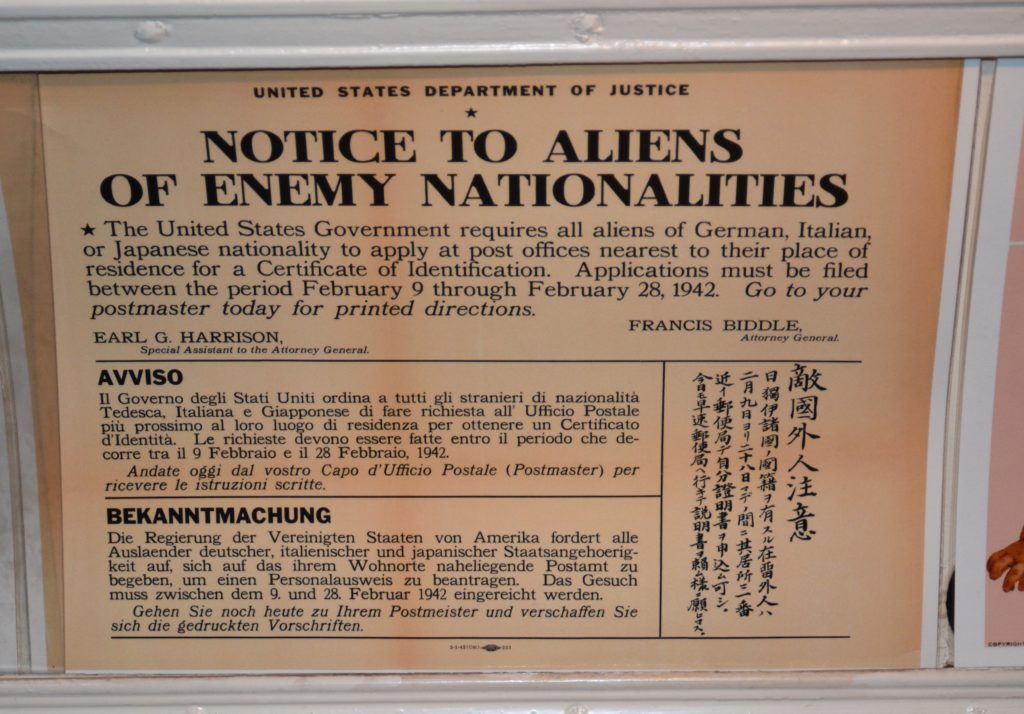

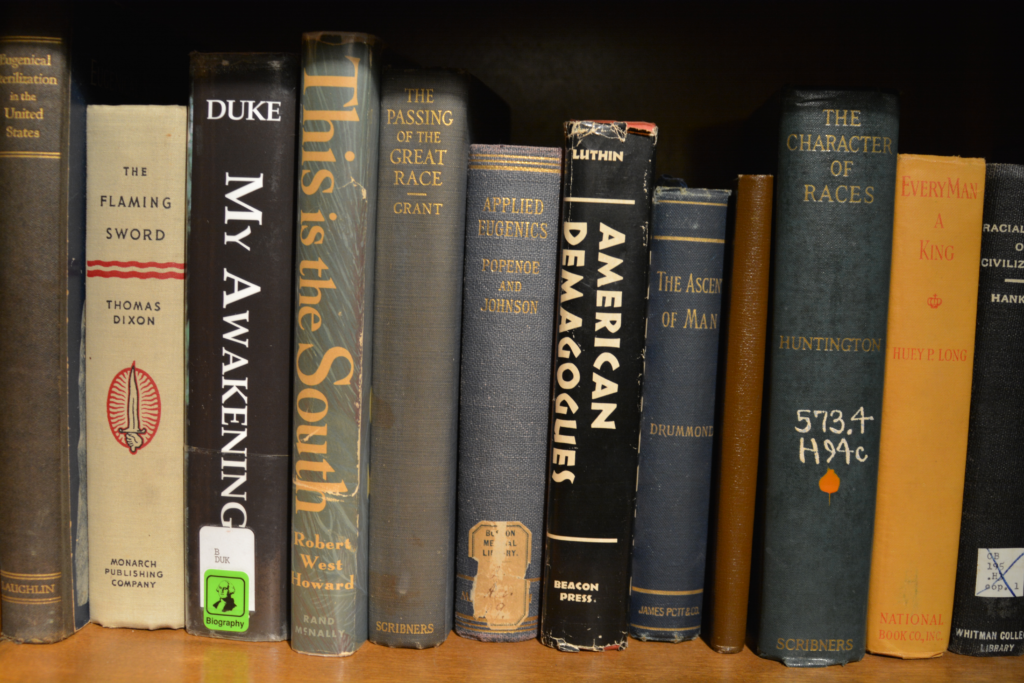

And I think it’s a mistake to think that kind of person-to-person, face-to-face kindness makes much difference when we are confronting evil. Survivors of the Bosnian genocides describe watching long-time friends rape their sister or kill their family. It isn’t as though Jews being nicer to and about Nazis would have prevented genocide. It wasn’t being nice to segregationists that ended the worst kind of de jure segregation. We have far too many videos that show being nice to police doesn’t guarantee a good outcome. People in abusive relationships can be as compassionate as an angel, and that compassion gets used against them. We will not end Nazism by being nice to Nazis.

That kindness, compassion, and non-conflictual rhetoric is sometimes the best choice doesn’t mean it’s always the only right choice. It can be (and often has been) a choice that enables and confirms extraordinary injustice. It’s often only a choice available to people not really hurt by the injustice. Machiavellian rhetoric is sometimes the best choice; it’s often not.