During the Black Lives Matter protests, there were a lot of arguments about the rhetorical effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) of the protests, and one recurrent argument was that the aggression and militancy of the protesters alienated potential allies. This particular argument went along these lines: “I’m not racist, and I’m very opposed to racism, but these protestors have alienated me through how they’re making their argument. If they want the support of people like me, they have to stop being so aggressive.” Let’s call the sort of person who makes this argument Chester.

[As an aside, Chester Burnette is the best dog that has ever lived, and so I always name the interlocutor Chester. Chester was male, so I’ll use “he,” but, of course, Chesters are not always male.]

I have an AB, MA, and PhD in Rhetoric. I am a professor in a Department of Rhetoric and Writing. So, I get rhetoric. I know that how you make your argument is tremendously important. My whole career has been spent trying to teach students that smacking your opposition over the head with your thesis, even if you repeat it five times, is not a great way to change anyone’s minds. What might seem compelling reasons to you won’t seem important to anyone else unless those reasons connect with a value your audience has (what, because of Aristotle, is often called “enthymematic reasoning”). So, it makes me happy that so many people expressed concern about how people argue.

Here’s what I understand Chester to believe. Chester’s opposition to racism is important to his sense of identity, and it is sincere. Some of the Chesters with whom I interacted, for instance, could talk about specific times they personally shut down someone who was racist. Still and all, it was interesting that, if the interaction went on, at some point Chester would express skepticism about whether there is really a problem of POC men (especially African– and Native-American) getting abused and even murdered by the police. Chester would almost always end up saying that there may be faults on both sides.

And he’d often appeal to his own experience to support the claim. He’s been pulled over, he’d say, sometimes for some bullshit reasons, but he kept his hands in view, answered the officer’s questions politely, and it all worked out fine. And he brings up his experience as an important piece of evidence in arguments about the police. Chester, by the way, is white. And, of course, the argument is about whether POC and especially POC men are treated badly by the police. It’s interesting that Chester doesn’t see the irrelevance of his experience.

At this moment, some Chesters will think I just made the issue about race, since I brought up Chester’s race. Some people believe that an issue is not about race until someone mentions race.

Here’s one way to think about that. We spend a lot of time at dog parks. Some people look away when their dog assumes the position, and then they try to walk away without picking it up. If I offer to pick up their dog’s shit, some people are nice about it, and some people act as though I’m the problem. I didn’t create the shit by naming it.

Does a doctor create cancer by naming it? Does a spouse only become abusive when someone calls that behavior abusive? Is a colleague’s bullying okay until the moment someone names it as bullying?

The answer, weirdly enough, for many people is yes. As long as it isn’t named, we don’t have to think about it, and we don’t have to do something about it. And so they are more angry with the person who names it than they are with the cancer, the abusive spouse, the bullying colleague.

Some Chesters were just made very uncomfortable by my using the word shit, and talking about dog shit. They think I should have found a different analogy, one that was more comfortable.

These Chesters are very nice people. Let’s call them Nice Chesters. They are people who bring you casseroles when something bad has happened, who arrange meal banks, who maintain the community garden, whose social media have lots of memes about positive thinking, who are kind to everyone. I like these people. The problem is that they want a world in which we only talk about positive things, and we don’t say anything offensive or uncomfortable (in rhetoric, we say, they are uncomfortable with violations of norms of decorum or civility).

But the dog did shit, and the person responsible for the dog shitting either picked it up or didn’t. Wanting a world in which we don’t talk about how some dog owners let their dogs shit and don’t pick it up is a world with a lot of dog shit. And if we want to solve the problem of dog shit, we have to name it. The problem doesn’t arise when we name it. That shit is there. Whether the dog owner saw it or not doesn’t matter—that shit is there. The problem gets worse when, because people don’t want to talk about shit, because it makes them uncomfortable, they don’t want to talk about people who don’t deal with their dog’s shit.

And we can only solve the problem of dog shit in dog parks (or lawns, or whatever) if we name it, and we name it as something lots of people allow to happen.

Racism is the dog shit of our world.

If we aren’t willing to have uncomfortable conversations about racism, conversations that make people as uncomfortable as my using the word shit, then we’re all looking away from the dog shit. We can’t talk about racism in our culture without being really uncomfortable.

The Nice Chesters believe that we don’t need to talk about those uncomfortable things in uncomfortable ways. They believe that, if we’re all nice to each other, everything will be fine. And that’s absolutely true. If we were all kind and loving and compassionate, then there wouldn’t be riots. There also wouldn’t be any need for riots because there wouldn’t be police officers protected from accountability. The problem is that a lot of the people who let their dogs shit and don’t pick it up aren’t nice, and there is no nice way to get that sort of person to pick it up. They just get angry.

I spent a lot of time looking at the rhetoric about slavery. Abolitionists said that slavers (many of whom liked to call themselves slaveowners or slaveholders) abused their slaves, and violated the very clear rules in Scripture about how to treat slaves. Slavers said those criticisms hurt their feelings. Many people said that the problem was that the abolitionists were too extreme in their rhetoric, and, if they were nicer, their message could get across. And so they tried to write nice criticisms of slavery—the slavers banned those writings too. It didn’t matter how nicely people said slavery was a sin; slavers didn’t want to hear it. There was no nice way.

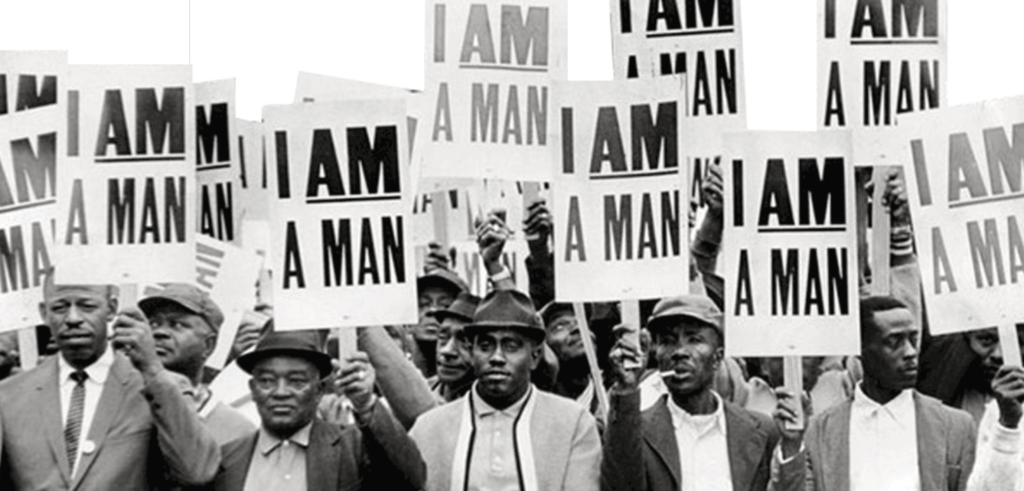

Frederick Douglass remarked on the desire for niceness in the abolition movement—the fantasy that, if African Americans were nice enough, if abolitionists asked nicely enough, supporters of slavery would change their minds. He said, “The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims have been born of earnest struggle. […] If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” (“West India Emancipation“)

Right now the kind of people who would have been fighting MLK every step of the way are trying to claim that he is an example for their “if you’re nice, people will hear you” argument. That wasn’t King’s argument, he wasn’t nice, and he didn’t persuade the James Kilpatrick’s or Bull Connors of the world at all, let alone by being nice.

King’s argument was that non-violence is disruptive, controversial, and conflictual, but he also argued that what his critics thought of as “peaceful” was simply conflict of which they could be unaware. King argued that nonviolence is effective in the long run because the means and ends are aligned.

On the whole, I’m in favor of non-violent protests, partially because I’m persuaded by the research that says non-violence is more effective. But even I have to say that I don’t know of any time that non-violence worked when it came to issues of racialized police brutality. The closest I can think of is when the Nazis tried to deport Jewish men married to non-Jewish women, but it isn’t a great fit.

If there are times that non-violent protests of police brutality worked, I’d love to hear about them. It’s important to think about how changes in policing have actually been effected because, as far as I can tell, Nice Chesters are calling on protesters to engage in a kind of protest that has never worked. But what I’m certain they’re doing is shifting the conversation from the issue of racialized policing and lack of accountability to the rhetoric of protesters.

Imagine that we are room-mates, and you are angry that I never do the dishes, and you want me to do the dishes. But, every time you bring up the issue, I say that you’re criticizing me in a way that makes me uncomfortable, and so we can’t continue the conversation. I insist that I’m open to thinking about the dishes, but only if you make the argument the right way. As long as I can keep us arguing about whether you’re arguing the right way, I can keep leaving dirty dishes in the sink.

If there is no right way for you to get me to think about what I’m doing with the dishes, then I’m I’m pretending I’m open to solving the problem, but I’m not.

So, how do we know if I’m arguing in bad faith?

First, can I set standards for how you’re supposed to argue that you can actually achieve? Second, if I set the standards, do I stick to them? (That is, do I keep moving the goalposts?) Third, can I name the conditions under which I would change my mind about what I’m doing with the dishes? Fourth, am I holding us both to the same standards in regard to how we argue? (That is, am I treating us as equals–or am I allowed to argue any way I want, but you have to be careful about your tone?)

I think Chester’s argument generally violates all four rules, especially the last.

After all, what if someone said to Chester, “I’d be open to your argument that we need to make our argument differently if you made it a different way”? Would Chester feel the need to change how he is making his argument? And yet that’s just as reasonable a request as Chester’s.

When I pointed this out to Chester—that Chester is saying others need to work to persuade him, but he doesn’t need to work to persuade them—he’d say something like, “Well, if you want to win the argument, you need white people on your side.”

That just gave away the argument. Chester is saying that our culture is racist. To say that POC have to please white people rhetorically is to say that political change only happens when white people care. It’s saying that white people are in power, that white people don’t experience the police this way, that white people don’t care about the experiences of POC. And that is the BLM argument.

So, if you argue that POC who are saying that a lot of white people just aren’t willing to acknowledge the racism of our culture need to defer to the feelings of white people for anything to change, you’re proving them right.