[Image from here.]

My father used to tell a story about when he met my mother’s grandmother–an Irish Democrat who loved Jimmy Walker. He asked how she could support him considering how corrupt he was. And her answer was that he couldn’t be corrupt because he was so nice, and he gave so much money to the church.

I’ve been recommending Jan-Werner Müller’s What is Populism since I read it recently—everyone should read it. Here I want to talk about what he says about corruption. His basic argument, as mentioned in a previous post, is one endorsed by many people—that far too many people are willing to be persuaded that only people like them really count when it comes to issues of public policy, laws, and rights. [1]

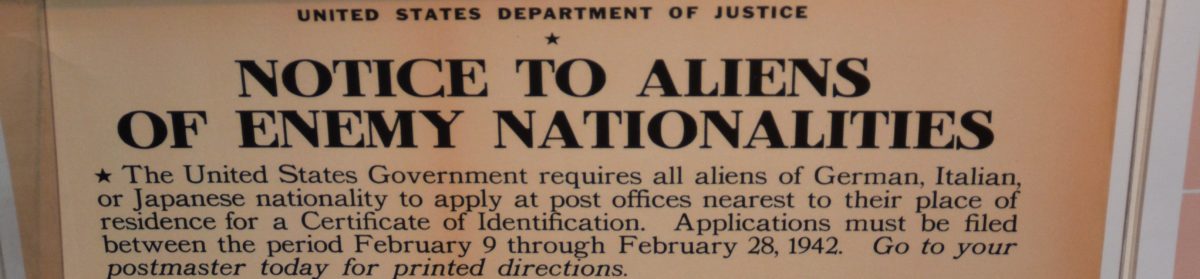

Unhappily, as Rogers Smith showed, we have always lived within a world of two notions of nationality: one based in in-group/out-group thinking (this group can be trusted in democratic deliberation), and an inclusive one based in the trusting democratic deliberation (which supports birth-right citizenship). The first is racist; the second understands that ideology is socially constructed.

Müller calls the first way of thinking about national identity “populism” (I’d quibble with that term, and call it toxic populism). As he says, that this notion of a real group that counts (Americans/Germans/Lutherans) versus people who don’t count (people with American/German citizenship or church membership who disagree with me) isn’t particular to any one place (or area) on the political spectrum—think Chavez (Bolivarian Marxist), Berlusconi (liberal-conservative), Lenin (Marxist-Leninist), or Trump (who is now being defended as a nationalist conservative). They, and many others, argue(d) that there isn’t a complicated world in which we need to find political solutions that are good enough for everyone and perfect for no one—the correct answer to any policy question is obvious to Us (real), and anyone who disagrees is Them (whose views can be dismissed). [2]

One of many brilliant things that Müller does is to connect that insight about people who think in terms of real v. unreal group members with the always puzzling aspect of so much demagoguery: that people condemn something, like corruption, as though they are on principle opposed to corruption, but, when an in-group member is engaged in exactly the same behavior, they dismiss, deflect, or praise that same behavior. They aren’t opposed to corruption on principle, but only rigidly opposed to out-group corruption.

Had Obama behaved exactly as Trump is—had as many family members on the White House staff, had those staff members go on a trip pushing their products, gone on far more vacations than other Presidents, and in a way that meant government funds went into his pockets, put in place tariffs that helped his daughter’s business—Trump’s supporters would have burst their own spines with rage. They would have called for impeachment.

But they aren’t calling for impeachment of Trump, or even calling what he does corruption, and why not? Müller argues that it’s because of populism’s reliance on “clientelism.” He says that “populists tend to engage in mass clientelism: the exchange of material and immaterial favors by elites for mass support. [….] What makes populists distinctive, once more, is that they can engage in such practices openly and with public moral justifications, since for them only some people are really the people and hence deserving of the support by what is rightfully their state.

“Similarly, only some of the people should get to enjoy the full protection of the laws; those who do not belong to the people or, for that matter, who might be suspected of actively working against the people, should be treated harshly.” (46)

Müller notes “the curious phenomenon that revelations about what can only be called corruption simply do not seem to damage the reputation of populist leaders as much as one would expect” (47). And he explains it: “Clearly, the perception among supporters of populists is that corruption and cronyism are not genuine problems as long as they look like measures pursued for the same of a moral, hardworking ‘us’ and not for the immoral or even foreign ‘them.’” (48)

They don’t see behavior that would have them foaming in the mouth on the part of opposition politicians (payoffs; nepotism; using the power of the government to settle personal scores, throwing business to cronies, coercing people to support dodgy foundations or stay at one’s hotel properties) as “corruption” on the part of leader they think really gets them—what Müller calls the populist.

Müller explains one reason that talking about Trump’s corruption (which is what his supporters would call it if Obama had done the same things) won’t work:

“It is a pious hope for liberals to think that all they have to do is expose corruption to discredit populists. They also have to show that for the vast majority, populist corruption yields no benefits, and that a lack of democratic accountability, a dysfunctional bureaucracy, and a decline in the rule of law will in the long run hurt the people—all of them.” (48)

While I completely agree about the pious hope, and I agree that the topoi [3] that Müller suggests are good ways to argue about our current situation, I think they won’t work with a lot of people. Müller is suggesting that we point out to people that the person and policy agenda they are supporting will hurt them in the long run because it sets into place a process that can be used against them.

That isn’t an argument on the stases of particular policies, parties, or political figures (which is where most current political discourse is); it’s an argument on the stasis of how we deliberate. And Müller is proposing three topoi not currently in play (which haven’t been for years): 1) we should think about current decisions in terms of what processes they put in place rather than what we get now (we should reject outcomes-based ethics); 2) we should make decisions about politics in terms of the long-term rather than short-term; 3) we should care about fairness across groups.

And I completely agree that we need to shift the stasis from whether this leader is demonstrably loyal to the in-group to whether our way of thinking about politics is a good way (which is what Müller is saying we should do), but I think it’s pretty hard.

One of the reasons it’s hard is that we don’t just have a large number of people who choose to consume only media that tells them their in-group is good and the out-group is bad (again, this happens all over the spectrum, so that Republicans who don’t support Trump are essentially socialists, there is no difference between Trump and Hillary Clinton, all Christians are Trumpagelicals, all critics of Trump are atheists, and so on), but that the self-identified “right wing” media has renarrated the ideal outcome of policy argumentation: as long as something Trump says or does angers (or “triggers”) “libs,” it’s a win for “conservatives.”

This is openly a shifting of public discourse being policy argumentation to being a bad version of a WWE performance—as long as you’ve hurt the other side, or made them unhappy, you’ve won. I’m starting to see the same argument being made about stigginit to “conservatives,” and that isn’t good.

This is wrong on so many levels. In the first place, that media isn’t “conservative” in any consistent ideological way—the current “conservative” talking points aren’t about policy but identity (we are good because we aren’t them). But, in this world, as long as the outcome of a policy or statement is “stigginit to the libs,” then many people think it’s good. The outcome is good. But that outcome is just making the other unhappy.

There are many other groups that define success in zero-sum terms—hurting them is a kind of winning, even if we’re hurt too—so this isn’t unique to people devoted to Trump, and so I think that Müller’s rhetorical project is really complicated. It’s right, but it’s complicated.

[1] A lot of people make that argument or a similar one. Berger talks about this as a characteristic of “extremism;” I’ve talked about it as a quality of the nastiest kinds of demagoguery; Jeremy Engels, Catherine Kramer, and other scholars of resentment talk about it; it shows up in discussions of polarization, such as Lilliana Mason’s work; scholars of racism, ranging from Zitkala Sa to James Cone, identify it as a crucial aspect of racism, and cultural critics like Ijeoma Oluo and Ta-Nehisi Coates write about it persistently. Policy argumentation is short-circuited by shifting the stasis to whether real Americans, Christians, composition scholars, dog lovers (“us”) are getting what they/we deserve.

[2] Just to reiterate: our policy options are not usefully reduced to political group identities, and those groups are not usefully reduced to a binary or continuum. The world is not a binary of people who agree with us and those who should be cast into outer darkness where there is weeping and gnashing of teeth.

[3] Topoi is a rhetorical concept that everyone should know. Topoi are kind of best thought of as rhetorical cliché—sometimes not usefully called a meme. A topos is the recurrent (disputable) claims within an argument—there are Muslim prayer rugs found in the Texas desert, the Democratic primaries were rigged, abolitionists inspire rebellion, the Bush family supported Nazis, these policies are unfair, these policies will have bad consequences.

There aren’t two sides on abortion. There aren’t two sides on gun control. There aren’t two sides on immigration. There are far more than two. But reducing a complicated issue to two sides is politically useful—as Hitler noted, it’s easier to persuade people if you make issues very simple, and as people have noted about Hitler’s rhetoric, that’s most effectively done by reframing the policy issue as simply one instance of the war between Us and a common enemy (Them). That reduction of complicated issues to “us v. them” is appealing to people and therefore profitable for media.

There aren’t two sides on abortion. There aren’t two sides on gun control. There aren’t two sides on immigration. There are far more than two. But reducing a complicated issue to two sides is politically useful—as Hitler noted, it’s easier to persuade people if you make issues very simple, and as people have noted about Hitler’s rhetoric, that’s most effectively done by reframing the policy issue as simply one instance of the war between Us and a common enemy (Them). That reduction of complicated issues to “us v. them” is appealing to people and therefore profitable for media.