A podcast with a Rhetoric PhD who is also a standup comic, consultant, Emmy-nominated comedy writer, and author.

https://rhetoricwarriors.com/podcast/rwp-117-flogging-the-demagogues-w-dr-trish-roberts-miller/

Retired Professor, Writing Center Director, Scholar of train wrecks in public deliberation

A podcast with a Rhetoric PhD who is also a standup comic, consultant, Emmy-nominated comedy writer, and author.

https://rhetoricwarriors.com/podcast/rwp-117-flogging-the-demagogues-w-dr-trish-roberts-miller/

I mentioned to someone that I thought people often mistake signs for proof, when signs aren’t even evidence. And that person asked for clarification, so here is the clarification.

What I was trying to say is that some people support their point via signs rather than evidence. I’ve often made the mistake of thinking that the people who appeal to signs rather than evidence misunderstand how evidence is supposed to work, but I eventually figured out that they don’t care about evidence. They care about signs. Explaining that point means going back over some ground.

A lot of people are concerned about our polarized society, identifying as the problem the animosity that “both sides” feel toward each other, and so the solutions seems to be some version of civility—norms of decorum that emphasize tone and feeling. I have to point out that falling for the fallacy of “both sides” is itself part of the problem, so this way of thinking about our situation makes it worse. The tendency to reduce the complicated range of policy affiliations, ideologies, ways of thinking, ways of arguing, depth of commitment, open-ness to new ideas, and so many other important aspects of our involvement with our polis to a binary or continuum fuels demagoguery. It shifts the stasis from arguing about our policy options to the question of which group is the good one. That is the wrong question that can only be answered by authoritarianism.

I think we also disagree about ontology. I’ve come to think that a lot of people believe that the world is basically a stable place, made up of stable categories of people and things (Right Answer v. Wrong Answers, Us v. Them). It isn’t just that the Right Answer is out there that we might be able to find; it’s that there is one Right Answer about everything, and it is right here–the Right People have it or can get it easily. We just need to listen to what the Right People tell us to do. I want to emphasize that these stable categories apply to everything—physics, ethics, religion, politics, aesthetics, how you put the toilet paper on the roll or make chili, time management, childraising….

There are many consequences of imagining the world is a place of fake disagreement in which there is one Right Answer that we are kept from enacting, and I want to emphasize two of them. First, in this world, there is no such thing as legitimate disagreement about anything. If two people disagree, one of them is wrong, and needs to STFU. Second, the goal of thinking is to get one’s brain aligned with the categories that are in the structure of the world (to see the Right Answer), and people who think about the world this way generally believe there is some way to do that. In my experience, people who believe the world presents us with problems that have obvious solutions are some kind of naïve realist, but it’s important that there are various kinds of naive realist (with much overlap).

There are naïve realists all over the political spectrum. That doesn’t mean I’m saying all groups are equally bad–that’s an answer to the question we shouldn’t waste our time asking [which group is the good one]. Instead of arguing about which group is good, we should be arguing about which way of arguing is better. I don’t think that there is some necessary connection between political ideology and epistemology—there are very few relativists (it’s hard to say that it’s wrong to judge other beliefs without making all the nearby cats laugh), but realists of various stripes I’ve read or argued with have been self-identified anarchist, apolitical, conservative, fascist, leftist, Leninist, liberal, Libertarian, Maoist, Nazi or neo-Nazi (aka, Nazi), neoconservative, neoliberal, objectivist, progressive, reactionary, socialist, and I’ve lost interest in continuing this list.[1] I’ve also argued with people from those various positions who are not realists (which is a weird moment when I’m arguing with objectivists), and it’s often the people who insist on the binary of realist v. relativist who actually appeal to various forms of social constructivism (Mathew McManus makes this point quite neatly).[2]

I’ve talked a lot about naïve realism in various writings, but I’ve relatively recently come to realize that there are a lot of kinds of naïve realism, and there are important differences among them. They aren’t discrete categories, in that there is some overlap as mentioned above, but you can point to differences (there are shades of purple that become arguably red, but also ones that are very much not red–naïve realism is like that). For instance, some people believe that the Truth is obvious, and everyone really knows what’s true, but some people are being deliberately lazy or dumb. These people believe you can simply see the Truth by asking yourself if what you’re seeing is true. I’ve tended to focus on that kind of naïve realism, and that was a mistake on my part because not all naïve realists think that way.

Many kinds of naïve realists believe that the Truth isn’t always immediately obvious to everyone, because it is sometimes mediated by a malevolent force: political correctness, ideology, Satan, chemtrails, corrupt self-interest, unclean engrams, or the various other things to which people attribute the inability of Others to see the obvious Truth.[3] These people still believe it’s straightforward to get to the Truth. It might be through sheer will (just willing yourself to see what’s true), some method (prayer, econometrics, reading entrails, obeying some authority), being part of the elect, identifying a person who has unmediated access to the Truth and giving them all your support, or through paying attention to signs, and that last one is the group I want to talk about in this post.

Belief in signs is still naïve realism—the Truth (who/what is Right and who/what is Wrong) can be perceived in an unmediated way, but not always; the Truth is often obscured, but also often directly accessible. These people believe that there are malevolent forces that have put a veil over the Truth, but that the Truth is strong enough that it sometimes breaks through. The Truth leaves signs.

It is extremely confusing to argue with these people because they’ll claim that one study is “proof” of their position (they generally use the word “proof” rather than evidence, and that’s interesting), openly admitting that the one study they’re citing is a debunked outlier. They’ll use a kind of data or argument that they would never admit valid in other circumstances—that some authors say there is systemic racism is a sign that those authors are Marxists, since that’s also what Marxists say. But, that the GOP says that capitalism tends toward monopoly doesn’t mean the GOP is Marxist, although that’s also what Marxists say. That one Black man, scientist, “liberal,” expert says something is proof that it’s true, but that another Black man, scientist, and so on say it isn’t true doesn’t matter. That a hundred Black men, scientists, and so on say it’s wrong doesn’t matter. Or, what I eventually realized is that it does sort of matter—it’s further proof that the outlier claim is True. That knowledge is stigmatized is proof that it is not part of the cloud malevolent forces place over the Truth—it’s one of the moments of Truth shining through. If you’ve argued with people like this, then you know that pointing out that relying on a photo, quote, or study that appears nowhere outside their in-group doesn’t suggest to them that there are problems with that datum; on the contrary, they take it as a sign that it’s proof.

Because they believe that the Truth shines through a cloud of darkness, or leaves clues scattered in the midst of obscurity, they prefer auto-didacts to experts, an unsourced heavily-shared photo to a nuanced explanation, someone whose expertise is irrelevant to the question at hand, polymaths, and people who speak with conviction and broad assertion over someone who talks in terms of probabilities.

Fields that use evidence such as law spend quite a bit of time thinking about the relative validity of kinds of evidence. Standards of good evidence are supposed to be content-free, so that there are standards of expertise that are applied across disciplines. We can argue about the relative strength of evidence, and whether it’s a kind of evidence we would think valid if it proved us wrong, but neither of those conversations have any point for someone who believes in signs rather than evidence. They’ll just keep repeating that there are signs that prove their point.

People who believe in degrees and kinds of evidence are likely to value cross-cutting research methods, disagreement, and diversity. People who believe that the Truth is generally hidden but shines out in signs at moments are prone, it seems to me, to see cross-cutting research methods and diversity as a waste of time, if not actively dangerous. They don’t see a problem with getting all their information from sources that confirm their beliefs; they think that’s what they should do. Yes, it’s one-sided, they’ll say—the side of Truth.

It’s because of that deep divide about perception that I often say that we have a polarized public not because we need more civility, as though we need to be nicer in our disagreements, but because we disagree about the nature of disagreement.

[1] Yes, I’ll argue with a parking brake, if it seems like an interesting one.

[2] I really object to the term “populist,” since it implies that the “elite” never engage in this way of thinking. That’s a different post.

[3] As an aside, I’ll mention that these people often believe that you either believe that there is a Truth, and good people perceive it with little or no difficulty or you believe that all beliefs are equally valid (a belief that pro-GOP media attribute, bizarrely enough, to “Marxism”—Marxists hate relativism). Acknowledging uncertainty doesn’t make one a relativist, let alone a Marxist. If it does, then Paul was both a relativist and a Marxist. He did, after all, say that “we see as through a glass darkly.” If you’d like to argue that Paul was a relativist and Marxist, I’m happy to listen.

I’ve spent forty years working with people in their late teens or early twenties, and then watching them navigate their twenties. And, for an awful lot of people, your twenties suck. Not as much as high school, but more than college. They suck for a bunch of reasons, and one of them is how much nostalgia people have about their twenties. Because, also, your twenties have some great things about them, and so nostalgia is easy. The problem is that far too many people in their forties and fifties (or older) only remember the good things, and so, in movies, memories, fiction, TV, they’re a carefree time. When you’re in them, they are not carefree.

As a culture, we memorialize people in their twenties as being free, with no responsibilities, able to do all sorts of impulsive things, with a world that has no commitments, including no romantic ones. We think of people in their twenties as people who can move anywhere, have folks over to a messy place and serve them cheap booze and bad weed, have a “dinner” party that is your best ramen recipe, drift in and out of hookups, spend a day in bed reading earnest literature or listening to angsty music or just playing a game, get a tat, wear nothing but a t-shirt and ripped jeans for months end.

And that’s sort of true, for some people with a particular background. And even for those people, the whole reason you could serve guests shitty alcohol and cheap food was that’s all any of you could afford. You could move anywhere and have drifty hookups because you had no responsibilities. But you had no responsibilities because you didn’t have a career, a stable enough living situation to get a dog, no particular connection to any one place, and often not a stable relationship. Another way to describe the twenties is not free of responsibilities, but unmoored.

I have seen people whom I knew in their twenties reminisce as though that time was wild and carefree. I remember what they were like. They were not carefree. They were at moments, but at other moments they were incredibly anxious about whether they’d find a career, make enough money to get a stable living situation, figure out where to live, be able to get a dog, find someone… How we look back on our lives, and how we lived it, don’t always match up. We think about those times differently because we know how that story ended, and so we forget how anxious we were about where the story would go. And it’s fine and great if we look back on our twenties with affection and nostalgia, but I think it’s harmful if, as people giving advice, or as a culture, we deny the angst and difficulties inherent to that age.

The twenties are really hard for a bunch of reasons. People’s brain chemistry changes, and so people suddenly start having issues they’ve never had before. Many people didn’t go to college, and they’ve spent the years since high school trying to figure out how to navigate a world that doesn’t have a path of upward mobility or decent benefits for skilled artisans. Many people go to college, and end up with a degree that has no clear career path. They don’t know what they want to do, they find that they are having trouble getting a foothold in a career, they’re expected to have a career plan without any information. They also find that jobs won’t hire them without experience, and they have no way to get experience. It’s rough. Many people finish college in order to go to grad school, and grad school sucks. Some people take a path or have a personality that means they never have to manage the changes presented by the twenties, and good for them, but they aren’t the norm.

In addition, for many people (including some who go on to grad school), all the signs that gave us confidence are gone—good grades, praise from teachers, getting to be Eagle Scout, winning a sports championship—and so we don’t know how to assess our performance. Are we failing to get jobs (dates, second dates, that apartment, raises, publications, the same level of success in grad school that we got in undergrad, and so on) because we’re bad, we’re good but not a good fit, good but with bad materials, it’s a rough market, looking in the wrong places, looking in the wrong ways, we aren’t capable of achieving our goals, we aren’t making the changes we need to make in order to achieve those goals, those are goals no one achieves?

Because we have lost the ground for our confidence, some people resort to arrogance, deciding that we are entitled to all the good things, exactly as we are, and doing exactly what we’re doing, and we should be enraged if we don’t get what we believe we’re entitled to get. We have been the best, and so we are entitled to be the best. I don’t think that’s a great choice, but I get that it’s attractive.

I think there are other ways that things change for people in their twenties that we don’t always remember when we look back on that era. For an awful lot of people, the behaviors and mindsets that got them to their twenties (or didn’t stop them from getting there) stop working as well and sometimes at all. All-nighters, relying on panic and shame to get things done, letting friendship come to you, random self-care, no self-care—for many people those behaviors start having costs they didn’t have before.

Some people just pay those costs, some people get lost, some people wander and are not lost, some people do the hard work of trying to figure out how to manage a new world, some people postpone the difficulty, and, well, so many other options. There are lots of ways to get through the twenties that will turn out fine, and lots of ways that aren’t so great.

I rather like Erik Erickson, and I find persuasive the notion that there are moments in our lives when we’ve got a lot of crap from the past and mixed messages from the present. And we have to figure out what we’re going to do about the fact that living life as we’ve lived it has put us into a crisis about who we are and what we want.

There are moments when we look in our closet, and it’s stuffed full. It’s full of things we thought we’d use, things we used to use, things we’d like to use, things that we use, things we will use if life plays out a certain way, things we’ve been told we should value, things we value we’ve been told we shouldn’t, things we’ll never use but like to think of ourselves as the sort of person who would use them, and so on.

I think the twenties are one of those moments of looking at that closet. (There are others.)

We might decide to keep shoving stuff in there and just not look. That’s always a choice.

If we pull it all out and try to figure out what to do with it, there will be a moment (or more) that is absolutely awful. We will look at all that shit, all over the fucking place, and just wish we’d never started. We have to make so many decisions when we don’t have the information to know what we’ll need and what we won’t. We can, of course, shove it back in. We can give it all away. We can do the hard work of thinking about it all, and deciding what to keep, what to store, what to give away, what to burn ritually, what to give away.

Later, when we’ve shoved everything back in, burned it all, gone through it thoughtfully, or whatever we did, it doesn’t seem so bad, and that’s when the nostalgia kicks in. I don’t think people need to remember the pain of our twenties on a regular basis, but I do think it’s helpful, if we’re talking to people in their twenties, not to present our nostalgic version as though that was all that happened. It happened, but it isn’t all that happened.

I used to teach a class on the rhetoric of free speech, since what you would think would be very different issues (would the ideal city-state allow citizens to watch dramas, should Milton be allowed to advocate divorce, should people be allowed to criticize a war, should we ban video games) end up argued using the same rhetoric. Everyone is in favor of banning something, and everyone is prone to moral outrage that others want to ban something. The Right Wing Outrage Media went into a frenzy about people trying to pull To Kill a Mockingbird from K-12 curricula, and “cancel culture” as though they were, on principle, opposed to censorship. Those same pundits are now engaged in a disinformation campaign about CRT, which they are trying to ban (or, in other words, “cancel”), as well as books that teach students their rights, mention LGBTQ, talk about systemic racism. And the biggest call for pulling books from curriculum, school, and public libraries is on the part of the GOP, which continues to fling itself around about cancel culture. Of course, those examples could be flipped: people who defended removing Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or To Kill a Mockingbird are now outraged at Maus being removed.

They aren’t the first or only group to claim to be outraged, on principle, about “censorship” at the same moment they’re advancing exactly the policy they’re claiming they are, on principle, outraged that others advocate. Everyone wants some book removed from K-12 curricula, school libraries, public libraries. We are all in favor of banning books.

I’m not saying that everyone is a hypocrite, that there’s not really a controversy, we’re all equally bad, or it’s all about who has the power. I’m saying that this disagreement too often falls into the rhetorical trap that so much public discourse does. We talk as though our actions are grounded in a principle to which we are completely and purely committed when, in fact, we violate it on a regular and strategic basis. It would be useful if we stopped doing that. We should argue about whether these books should be banned, and not about banning books in the abstract.

There are several problems with how we argue about “censorship.” One is that we often conflate boycotting and banning, and they’re different. If you choose not to listen to music that offends you, give money to businesses or individuals who promote values or advocate actions that you believe endanger others, refuse to spend Thanksgiving dinner with a relative who is abusive, that isn’t “cancel culture.” It’s making choices about what you hear, read, or give your money to. Let’s call that boycotting. This post is not about boycotting, but about banning, about restricting what others can hear, read, watch, or learn. For sake of ease, I’ll call that “banning books.”

We’re shouting slogans at one another because we aren’t arguing on the stasis (that is, place) of disagreement. It’s as though we were room-mates and you wanted me to do my dishes immediately, and I wanted to do them once a day, and we tried to settle that disagreement by arguing about whether Kant or Burke had a better understanding of the sublime. We’ll never settle the disagreement if we stay on that stasis. We’ll never settle the issue about whether Ta-Nehisi Coates’ books should be banned from high school libraries if we’re pretending that this is an issue about whether book banning is right or wrong on principle.

The issue of banning books that we’re talking about right now actually has a lot of places of agreement. Everyone agrees that it is appropriate to limit what is taught in K-12, and what public and school libraries make available (especially to children). Everyone agrees that the public should have input on those limits and that availability. Everyone also agrees that it’s appropriate to limit access to material that is likely to mislead children, especially if it is in such a way that they might harm themselves or others. We also agree that mandatory schooling is necessary for a well-functioning democracy.

We disagree about when, how, and why to ban books because we really disagree about deeper issues regarding how democracy functions, what reading does, what constitutes truth, and how people perceive truth. We are not having a political crisis, as much as rhetorical one that is the consequence of an epistemic one.

It makes sense to start my argument with our disagreements about democracy, although the disagreements about democracy aren’t really separable from the disagreements about truth. Briefly, there are many different views as to democracy is supposed to function. I’ll mention only five of the many views: “stealth democracy” (see especially page two; this model is extremely close to what is called “populism” in political science), technocracy, neo-Hobbesianism, relativism, pluralism. And here is my most important point: none of these is peculiar to any place on the political spectrum. Our world is demagogically described as left v. right, just because that sells papers, gets clicks, and mobilizes voters. Our political world is, in fact, much more complicated, and the competing models of democracy exemplify how we aren’t in some false binary of left v. right. Every one of these models has its advocates everywhere on the political spectrum–not evenly distributed, I’ll grant, but they’re there. As long as we try to think about our political issues in terms of whether “the left” or “the right” has it right, we’ll never have useful disagreements on issues like book banning. So, back to the models.

“Stealth democracy” presumes that “the people” really consists of a group with homogeneous views, values, needs, and policy preferences. There isn’t really any disagreement among them as to what should be done; common sense is all one needs to recognize what the right decisions are in any situation, whether judicial, domestic or foreign policy, economic, military, and so on. Expert advice is reliable to the extent that it confirms or helps the perceptions of these “real” people, who rely on “common sense.” This kind of common sense privileges “direct” experience, claiming that “you can just see” what’s true, and what should be done. Experts, in this view, have a tendency to complicate issues unnecessarily and introduce ambiguity and uncertainty to a clear and certain situation.

So, how do advocates of stealth democracy explain disagreement, compromise, bargaining, and the slow processes of policy change? They believe that politicians delay and dither and avoid the obviously correct courses of action in order to protect their jobs, because they’re getting paid by “special interests,” and/or because they’ve spent too much time away from “real” people. They deflect that other citizens disagree with them by characterizing those others as not “real” people, dupes of the politicians, or part of the “special interests.”

In short, there are people who are truly people (us) who have unmediated perception of Truth and whose policies are truly right. We rely on facts, not opinions. In this world, there is no point in listening to other points of view, since those are just opinions, if not outright lies. Just repeat the FACTS (using all caps if necessary) spoken by the pundits who are speaking the truth (and you know it’s the truth without checking their sources, not because you’re gullible, but because true statements fit with other things you believe). Bargaining or negotiating means weakening, corrupting, or damaging the truly right course of action. What we should do is put real people in office who will simply get things done without all the bullshit created by dithering and corrupt others. Dissent from the in-group is not just disloyalty, but dangerous. Stealth democracy valorizes leaders who are “decisive,” confident, anti-intellectual, successful, not particularly well-spoken, impulsive, and passionately (even fanatically) loyal to real people.

People who believe in stealth democracy believe that educating citizens to be good citizens means teaching them to believe that the in-group (the real people) is entirely good, whose judgment is to be trusted.

Technocracy is exactly the same, but with a different sense of who are the people with access to the Truth—in this case, it’s “experts” who have unmediated perception, know the “facts,” whereas everyone else is relying on muddled and biased “opinion.” Believers in technocracy valorize leaders who can speak the specialized language (which might be eugenics, bizspeak, Aristotelian physics, econometrics, neo-realism, Marxism, or so many other discourses), are decisive, and certain of themselves. And technocracy has, oddly enough, exactly the same consequences for thinking about disagreement, public discourse, dissent, and school that stealth democracy does.

In both cases, there is some group that has the truth, and truth can simply be poured into the brains of others—if they haven’t been muddled or corrupted by “special interests.” They agree that taking into consideration various points of view weakens deliberation and taints policies—the right policy is the one that the right group advocates, and it should be enacted in its purest form. They just disagree about what group is right. (In one survey, about the same number of people thought that decisions should be left up to experts as thought decisions should be left up to business leaders, and I think that’s interesting.)

Both models agree that school can make people good citizens by instilling in students the Truths that group knows, while also teaching them either to become members of that group, or to defer to it. Because students should learn to admire, trust, and aspire to be a member of that group, there is no reason to teach students multiple points of view (since all but one would be “opinion” rather than “fact”), skills of argumentation (although teaching students how to shout down wrong-headed people is useful), or any information that makes the right group look bad (such as history about times that group had been wrong, mistaken, unjust, unsuccessful). Education is indoctrination, in an almost literal sense—putting correct doctrine into the students.

I have to repeat that there are advocates of these models all over the political spectrum (although there are very few technocrats these days, they seem to me evenly distributed, and there are many followers of stealth democracy everywhere). In addition, it’s interesting that both of these approaches are, ultimately, authoritarian, although advocates of them don’t see them that way—they think authoritarianism is a system that forces people to do what is not the obviously correct course of action. They both think authoritarianism is when they don’t get their way.

Hobbesianism comes and goes in various forms (Social Darwinism, might makes right, objectivism, “neo-realism,” some forms of Calvinism, what’s often called Machiavellianism). It posits that the world is an amoral place of struggle, and winning is all that matters. If you can break the law and get away with it, good for you. Everyone is trying to screw everyone else over, so the best approach is to get them first—it is a world of struggle, conflict, warfare, and domination. Democracy is just another form of war, in which we can and should use any strategies to enable our faction to win, and, when we win, we should grab all the spoils possible, and use our power to exterminate all other factions. Schooling is, therefore, training for this kind of dog-eat-dog world, either by training students to be fighters for one faction, or by allowing and encouraging bullying and domination among students. The curriculum and so on are designed to promote the power and prestige of whatever faction has the political control to force their views on others. There is no Truth other than what power enables a group to insist is true. As with the other models, taking other points of view seriously just muddies the water, weakens the will, and, with various other metaphors, worsens the outcome. People who ascribe to this model like to quote Goering: “History is written by the victors.”

I’m including relativism simply because it’s a hobgoblin. I’ve known about five actual relativists in my life, or maybe zero, depending on how you define it. “Relativist” is the term people commonly use for others (only one of the people I knew called themselves relativists) who say that there is no truth, all positions are equally valid, and we should never judge others. In fact, relativists are very judgmental about people who are not relativist (I have more than once heard some version of, “Being judgmental is WRONG!”), and they generally stop being relativist very fast when confronted with someone who believes that people like them should be exterminated or harmed.

Stealth democrats and Hobbesians are often effectively sloppy moral relativists, in that they believe that the morality of an action depends on whether it’s done by an in-group member (stealth democracy) or is successful (Hobbesians). But they also, in my experience, both condemn relativism, because they don’t see themselves as relativists, as much as people who are so good in one way that they have moral license to behave in ways that they fling themselves around like a bad ballet dancer if engaged in by an out-group. On Moral Grounds.

Pluralism assumes that any nation is constituted by people with genuinely different needs, values, priorities, policy preferences, experiences. Therefore, there is no one obviously correct policy, about which all sensible people agree. Since sensible and informed people disagree, we should look for an optimal policy, a goal that will involve deliberation and negotiation. The optimal policy isn’t one that everyone likes—in fact, it’s probably no one’s preferred policy—but neither is it an amalgamation of what every individual wanted. It’s a good enough policy. Considering various points of view improves policy deliberation, but not because all points of view are equally valid, or there is no truth, or we are hopelessly lost in a world of opinion. Some advocates of pluralism believe that there is a truth, but that compromise is part of being an adult; some believe in a long arc of justice, and that compromises are necessary; some believe that truth is not something any one human or group has a monopoly on; some believe that the truth is that we disagree; some people believe that, for now, we see as through a glass darkly, but we can still strive to see as much and as clearly as possible, and that requires including others who, because they’re different, are part of a larger us. The foot is not a hand, the eye is not an ear, but they are all equally important parts of the body. We thrive as a body because the parts are different.

So, how does pluralism keep from slipping into relativism? It doesn’t say that all beliefs are equally valid, but that all people, actions, and policies are held to the same standards of validity—the ones to which we hold ourselves. We treat others as we want to be treated. We don’t give ourselves moral license.

And, now, finally, back to the question of book banning.

We all want to restrict books from schools and libraries. We disagree about which books because we disagree about which democracy we want to have. Do we believe that giving students accurate information about slavery, segregation, the GI Bill, housing practices and laws will make them better citizens, or do we believe that patriotism requires lying to them about those facts? Or, at least, pretending they didn’t happen? Do we imagine that a book transmits its message to readers, so that a het student reading a book that describes a gay relationship in a positive way might be turned gay?[1] Do we believe that citizens should be trained to believe that only one point of view is correct, to manage disagreement productively, to listen to others, to refuse to judge, to value triumph over everything, or any of the many other options? When we say books will harm students, what harm are we imagining? Are we worried about normalizing racism because that violates the pluralist model, normalizing queer sexualities because that violates the stealth democracy model, having students hear about events like the Ludlow Massacre since that troubles the Hobbesian model?

We don’t have a disagreement about books. We have a disagreement about democracy.

[1] One of the contributing factors to my being denied tenure was that I taught a book that enraged someone on the tenure and promotion committee. I didn’t actually like the book, and was using it to show how a bad argument works. He assumed you only taught books that had arguments you wanted your students to adopt. In other words, he and I were operating from different models of reading. One topic I haven’t been able to cover in this already too long post is about lay theories of reading in book banning. My colleague Paul Corrigan is working on this issue, and I hope he publishes something soon.

I know that I spend so much time talking about paired terms that people are probably tired of it. But, once you learn to recognize when someone is arguing used binary paired terms, then suddenly so many otherwise inexplicable jumps in disagreements make sense.

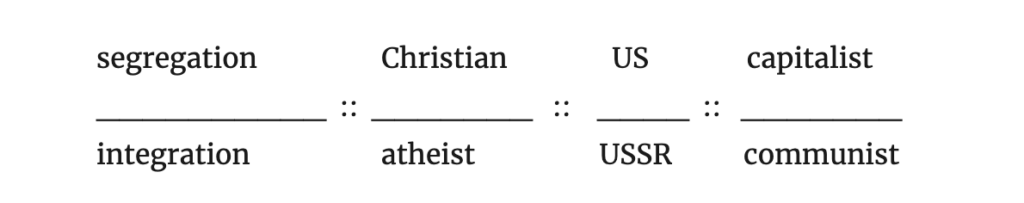

Just to recap, binary paired terms are sets of binaries (Christian/atheist, capitalist/communist) that are assumed to be logically equivalent—the preferred term in each pair is equivalent (and necessarily chained to) all the other good terms; and all of them are opposed to other terms that are equivalent (and chained to) all the other bad terms. Christian is to communist as capitalist is to communist—all communists are atheists, all Christians are capitalists.

When someone (or a culture) is looking at the world through binary paired terms, then it seems reasonable to make an inference about an opposition’s affirmative case or identity simply because they’ve made a negative case. It’s fallacious. It’s assuming that, if you say A is bad, you must be saying B is good, as though the world of policy options is reduced to A and B.

For instance, segregationists who believed that segregation was mandated by Scripture (an affirmative case: A [segregation] is good) thought they were being reasonable when they assumed that critics of segregation (negative case: A is bad) were making an affirmative case for communism (B is good)—segregation is Christian; communists are the opposite of Christian; therefore, critics of segregation are communists. The important point is that people who believed that particular set of binary paired terms believed that it wasn’t possible to be Christian and critical of segregation.

Thinking in binary paired terms isn’t limited to one spot on the political spectrum, nor to any spot on the spectrum of educational achievement/experience. Nor are the binary paired terms the same for everyone, and they can change over time. For instance, now many conservative Christians (exactly the point on the religious spectrum that advocated slavery and then segregation) claim that Christians were opposed to segregation because MLK was Christian, thereby ignoring that the major advocates of segregation were white Christian churches and leaders, and even universities, like Bob Jones. They are ignoring that there were Christians on all sides of that argument.

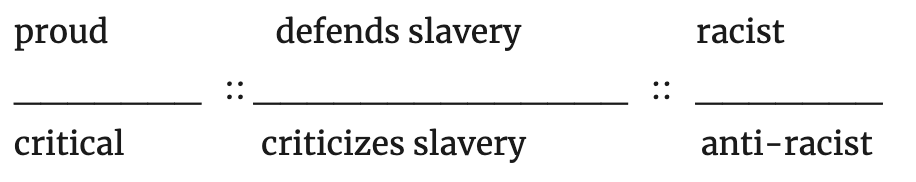

Consider these sets of paired terms. For some people, being proud is the opposite of being critical; for some, it’s the opposite of being ashamed. Thus, for the first set of people, if you’re proud of the US, or proud of being an American, then you must think everything the US did is good; therefore, you think slavery was okay, and you must be racist. So, they assume that, if you say you’re proud of the US, or you fly a flag, then you’re a defender of slavery. Their set of terms is something like this:

For the other group, the terms are something like this:

So, while we might put those two arguments in opposition to each other (anti- v. pro-CRT, for instance), it’s interesting that they are both positions from within a world that assumes similarly binary paired terms. The whole controversy ends if we imagine that being proud and critical are possible at the same time—that is, if we dismantle the binary paired terms.

When I criticize, for instance, some practice of GOP politicians as authoritarian (or a GOP pundit for advocating authoritarianism), a supporter of the GOP will surprisingly often answer, “It’s the Dems who are authoritarian,” as though that’s a refutation. (The same happens when I criticize Dems, Libertarians, Evangelicals, or just about any other group.) That response doesn’t make any sense, unless you are working from within binary paired terms.

If Dems are the opposite of the GOP, and Dems are authoritarian at all, then they occupy the slot for authoritarian, and GOP must be anti-authoritarian.

Of course, that’s entirely false. Both parties might be authoritarian, they might be different degrees of authoritarian, neither party might be authoritarian per se but either party might, at this moment, be advocating an authoritarian policy. Instead of arguing which party is authoritarian (as though that gives a “get out of authoritarianism free” card to “the” other), we should argue about whether specific policies or rhetoric are authoritarian, but you can’t do that if you approach all issues through binary paired terms.

Another important and damaging set of paired terms begins with the false binary of talk v. action. It’s both profoundly anti-deliberative, but anti-democratic. And it’s so pervasive that we don’t even realize when we’re assuming it.

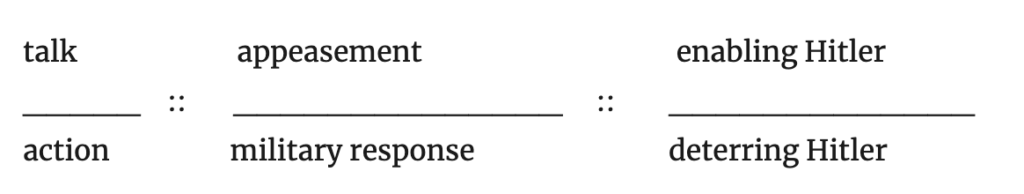

I got a really smart and thoughtful email about Rhetoric and Demagoguery, and the person raised the question of whether the desire for deliberation can be destructive, citing the instance of appeasing Hitler. And a common understanding of the appeasement issue is that people tried to deliberate with and about Hitler rather than take action, when action was what was necessary.

For reasons I’ll mention toward the end of this post, I am writing a chapter about the rhetoric of appeasement for the current book project, so I can answer that question. The answer is actually pretty complicated, but the short answer is that the British leaders never deliberated with Hitler, and the British public had severely constrained public discourse about Nazism and Hitler—so constrained that I’m not sure it counts as deliberation.

When we think in binary paired terms, one of the pair is narrowly defined (often implicitly rather than explicitly), and the other is everything else. When it comes to the issue of appeasing Hitler, “action” is implicitly narrowly defined as military action, and everything else is seen as “talk.” But talk is not necessarily deliberation. British leaders didn’t deliberate with Hitler; they bargained with him. Hitler didn’t bargain with British leaders; he deflected and delayed. I don’t think more talking with Hitler would have prevented war, and he wasn’t capable of deliberation (his discussions with his generals show that to be the case). But that doesn’t mean that military action would have prevented war. I used to think that going to war over Czechoslovakia would have been the right choice, but it turns out that course of action had serious weaknesses, as would sending troops in to prevent the militarization of the Rhineland (for more on the various alternatives to appeasement, see especially this book). The short version is that many of the military actions are advocated on the grounds that they would have deterred Hitler, a problematic assumption.

There were other actions that I’ve come to think probably had a higher likelihood of preventing war, such as Britain and the US refusing to agree to such a punitive treaty in 1919, insisting that the Kaiser explicitly agree to a treaty (i.e., not letting him and Ludendorff throw it onto the democracy), enacting something like the Dawes plan long before they did, either explicitly renegotiating the Versailles Treaty or enforcing it. In other words, preventing the rise of Nazism would have been the better course of action.

There are other counterfactuals people advocate: a mutual protection pact with the USSR, preventing France and Belgium from occupying the Ruhr, a different outcome for the Evian Conference, the US joining the League of Nations, a more vigorous response to the aggressions of Japan and Italy, the UK rearming long before it did, intervention in the Spanish Civil War. But, for various reasons, almost all of those options were rhetorical third rails–it was career-ending for a political leader to advocate any of them. The problem wasn’t that the UK engaged in talk rather than action, but that it didn’t talk about all the possible actions it might take, while the US didn’t deliberate about the issue at all.

The British public discourse about Hitler and the Nazis was severely constrained by the isolationism of the US, political complications in France, an unwillingness to deliberate about basic assumptions regarding what caused the Great War or what Hitler wanted, demonizing of the USSR, shared narratives about Aryanism, racism about Jews, Slavs, and immigrants generally.

But, many people ignore all those complexities, and imagine the situation this way:

All the various actions that weren’t appeasement, but that weren’t military response, disappear from this way of thinking. And, to be blunt, that’s how the popular discourse about appeasement works.

So, why did I decide to write a chapter about appeasement?

Because I believed that the UK had ignored the obvious evidence that Hitler was obviously not appeasable and it was obvious that they should have responded more aggressively. In other words, I accepted the reductive binary paired terms about the situation. I was wrong.

Binary paired terms are pervasive and seductive, and we all fall for them. Obviously.

I was just on Andrew Keen’s show “Keen On” to talk about Speaking of Race.

You can watch it here.

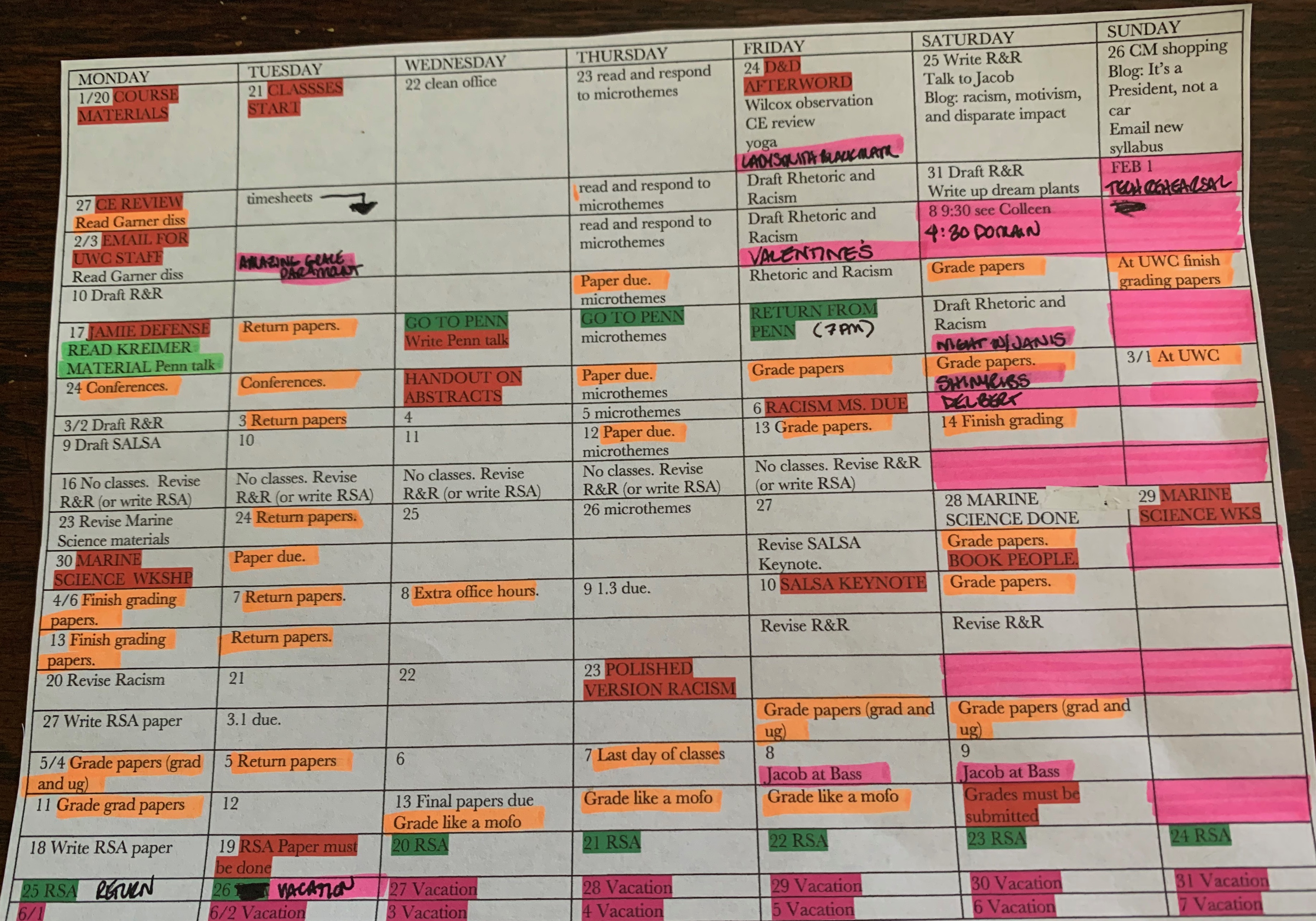

A while ago (probably several months), someone said they hated planning, and I’ve been meaning since then to write a blog post about it. It’s even been on my to-do list since then. To some people, that might look ironic–here I am giving advice about planning when I have been planning to do something for months and not getting to it.

That only seems ironic if we imagine planning to do something as making an iron-clad commitment we are ethically obligated to fulfill immediately. Thinking about planning that way works for some people, but for most people, it seems to me, it’s terrifying and shaming.

Planning isn’t necessarily a process that guarantees you’ll achieve everything you ever imagine yourself doing, let alone as soon as you first imagine it. Nor does planning require that you make a commitment to yourself that you must fulfill or you’re a failure. It’s about thinking about what must v. what should v. what would be nice to get done, somehow imagined within the parameters of time, cognitive style, resources, energy, support, and various other constraints. Sometimes things you’d like to get done remain in your planning for a long time.

There are people who are really good at setting specific objectives and knocking them off the list, who believe that you shouldn’t set an objective you won’t achieve, and who are very rigid about planning. They often get a lot done, and that’s great. I’m glad it works for them. Unfortunately, some of them are self-righteous and shaming because they assume that this system–because it works for them–can work for everyone. That it clearly doesn’t is not a sign that the method is not a universally valid solution, but a sign of the weakness on the part of people for whom it doesn’t work. They insist that this (sometimes very elaborate) system will work if you apply yourself, not acknowledging different constraints, and so they end up shaming others. They seem to write a lot of the books on planning, as well as blog posts.

And that’s the main point of this post. There is a lot of great advice out there about planning, but an awful lot of it is clickbait self-help rhetoric. There’s a lot of shit out there. There are some ponies. But there is so much shaming.

There are a lot of good reasons that some people are averse to planning—reasons about which they shouldn’t be ashamed. People who’ve spent too much time around compulsive critics or committed shamesters have trouble planning because they know that they will not perfectly enact their plan, and so even beginning to plan means imagining how they will fail. And then failure to be perfect will seem to prove the compulsive critic or committed shamester right. Thus, for people like that, making a plan is an existential terrordome. Personally, I think compulsive critics and committed shamesters are all just engaged in projection and deflection about how much they hate themselves, but that’s just one of many crank theories I have. Of course we will fail to enact our plan—nothing works out as planned—because we cannot actually perfectly and completely control our world. In my experience, compulsive critics and committed shamesters are people mostly concerned about protecting their fantasy that the world is under (their) control.

People who have trouble letting go of details find big-picture planning overwhelming; people who loathe drudgery find it boring; people trying to plan something they’ve never before done (a dissertation, wedding, trip to Europe, long-term budget) just get a kind of blank cloud of unknowing when they think about making a plan for it. People who are inductive thinkers (they begin with details and work up) have trouble planning big projects because it requires an opposite way of thinking. People who are deductive thinkers can have trouble imagining first steps. People who use planning to manage anxiety can get paralyzed when a situation requires making multiple plans.

I think planning of some kind is useful. I think it’s really helpful, in fact, and I think—if people can find the right approach to planning—it can reduce anxiety. But it is never to going to erase anxiety about a high-stakes project. And a method of planning shouldn’t increase anxiety.

Because there are different reasons that people are averse to planning, and people get anxious in different ways and moments, there is no process that will work for everyone. If a process doesn’t work for you, that doesn’t mean you’re a bad person, or you’ll never be able to plan; it just means you need to find a process that works for you. And, to be blunt, that process might involve therapy (to be even more blunt, it almost always does).

Here are some books that people trying to write dissertations have found helpful. Anyone who wants to recommend something in the comments is welcome to do so, and it’s especially helpful if people say why it worked for them. Some of these are getting out of date, and yet people still like them.

Choosing Your Power, Wayne Pernell (self-help generally)

Destination Dissertation, Sonja Foss and William Waters

Getting Things Done, David Allen (the basic principle is good, but it’s getting very aged in terms of technology)

Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey (another one that is getting long in the tooth)

I haven’t done much with this website, but the research is strong: https://woopmylife.org/

There are some things that can help. If you don’t like planning because it’s drudgery, then make it fun. Buy a new kind of planner every year. Use colors to code your goals. If planning paralyzes you because of fear of failure, then set low “must” goals that you can definitely achieve, and have a continuum of what should get done. Get into some kind of group that will encourage you. If you feel that you’re facing a white wall of uncertainty, work with someone who has done what you’re trying to do (e.g., your diss director) to create a reasonable plan. This strategy works best if they see part of their job as reducing anxiety, and if they have a way of planning that works with yours.

One of the toxically seductive things about being a student is that you don’t have to have a plan through most of undergraduate and even graduate school. You have to pick a major, but it’s possible to pick one not because of any specific plan–it’s the one in which we succeed (a completely reasonable way to pick a major, I think), and then we might go to graduate school in that thing at which we’re succeeding (it makes sense), and in graduate school we’re given a set of courses we have to take. The “plan,” so to speak, might be nothing more than “complete the assignments with deadlines set by faculty.” Those deadlines are all within a fifteen week period, and it’s relatively straightforward to meet them through sheer panic and caffeine. Then, suddenly (for many people), we are supposed to have a plan for finishing your dissertation, with deadlines that are years apart, for things we’ve never done—a prospectus, a dissertation. We have to know how to plan something long-term, with contingencies.

In my experience, planning in academia means being able to engage in a multiple timeline plan. Having one plan that requires that you get a paper accepted by this time, a job by that time, a course release by then increases anxiety. It seems to me that people tend to do better with an approach that enables a distinction between hard deadlines (if this doesn’t happen by that date, funding will run our) and various degrees of aspirational achievements.

I think this challenge is present in lots of fields: you can’t determine to hit a certain milestone, as much as hope to do so, and try to figure out what things you can do between now and then to make that outcome likely. Thus, there are approaches out there helpful for that kind of contingent planning. But, just to be clear, there are a lot that really aren’t.

I also think it’s helpful to find a way of planning that is productive given our particular habits, anxieties, ways of thinking. People who are drawn to closure seem to thrive with a method that is panic-inducing for people who are averse to it, for instance. So, it might take some time to find a method (it took me till well into my first job, but that was before the internet).

Writing a dissertation is hard; there is nothing that will make it easy. There are things that will make it harder, and doing it without a way of planning that works fits personality, situation, and so on is one. But there is no method of planning that will work for everyone, and there is no shame if some particular method isn’t working.

I recently found my notes and files from when I was writing my dissertation. I’ll start with saying that I’ve had a respectable publishing career, but hooyah, that dissertation was a hot steaming mess. So was my process of writing it. So, if you’re trying to write a dissertation, and you’re in the midst of a chaotic writing process and you think that what you’re writing is awful, it can’t be worse than either my process or product. You’ll be fine.

There’s a longer version of this, but here I’ll list a few ways that things went wrong. First, I was trying to use a technology that lots of people used (a notecard system), but it really didn’t work for me. I didn’t know that, and I couldn’t have known it till I tried it. It got me too caught up in details, and I’m an inductive thinker (and writer), and it worsened all the flaws of inductive writing (assuming that if you give enough details people will infer your argument).

There are lots of technologies that people now use—zotero, commenting on pdf—and they work for some people and not for others. If one that other people are using doesn’t work for you, then committing to it with more will won’t make it work. It doesn’t mean you’re a failure; it means there’s a bad match between that technology and you, and the technology needs to go.

Second, I was working with faculty who were not in the conversation I was trying to enter. That was simply a function of my topic and department. My committee was really good, but they couldn’t tell me what to read or what conferences to attend. Make sure someone on your committee knows the conversation, or change the conversation.

Third, I was modelling my argument on books I admired that were written by advanced scholars. Your dissertation, in terms of scope and structure, should be modelled on books written by junior scholars or other dissertations in your department.

Fourth, people writing their dissertations should be prohibited from making any major decisions regarding things like marriage.

Fifth, I was in a highly competitive department in which something like a writing group would probably not have been helpful, but I wish I had found one. It’s hard, though, since people outside your field will often give advice that isn’t appropriate for yours.

How things went right.

First through fifth: my dissertation director was a smart, insightful, and kind person. He was a student of Thomas Kuhn’s, and so stepped back and saw processes. When you’re writing a dissertation, there are moments you are completely paralyzed. It’s because we’ve often gotten through undergrad and coursework without thinking about structure very much. So, you go from thinking about how to structure a 20-page paper (or not, you just make it a list) to how to structure something that is 200 pages. You have to decide what’s background, where to explain that background, how to position yourself in regard to other scholarship, how much of that scholarship to discuss, where to start…so many things that just don’t come up in a seminar paper.

My director, Arthur Quinn, taught a course about 18th century rhetoric that was entirely histories of the 18th century that happened to emphasize rhetoric, and we spend the semester talking about their methods, structures, assumptions, rhetoric. It was one of four classes I had in that program that were historiography (maybe five), but I didn’t know that at the time. What I did know is that he was asking us to step up a ladder, from just thinking about our data, or our argument, to the various ways we might make that argument. That course influenced every single grad course I taught.

At one point, completely paralyzed in my writing, I was in a grad student office, rearranging the Gumby-like figures my office-mate had into a baseball game. His office was next door, and he stopped, looked in, and then went to his office. A while later, he came into my office and said, “Here’s what you’re arguing.” He gave me an outline for my dissertation. I started writing again.

My dissertation did not end up with that outline. But his giving me that direction got me writing. He was generally a hands-off director, but he knew the moment he had to step in.

Now that I’ve seen a lot of grad students, and a lot of directors, I appreciate him so much. A lot of scholars rely on panic to motivate themselves, and so they sincerely believe they are helping their students when they deliberately work their students into a panic. Many rely on shaming themselves in order to write, and so they think that shaming students is helpful. Some forget how hard it is to write a dissertation, and so they dismiss or minimize the concerns of their students. Some believe that they benefitted from how isolating writing a dissertation is, and so they believe that refusing to give directive advice is helping their students. Some have writing processes in which you have to have the entire argument determined before you start, and so they insist their students do. Some drift around in data and so encourage their students to do so. All of these processes work for someone—that’s why people adopt them—but none of them work for all students, and none of them work for any one student all the time.

And that is what Art Quinn taught me.

There’s a joke my family used to tell.

Two parents have twins who are each irritating in their own way. One is relentlessly pessimistic and griping, and the other irritatingly optimistic. Finally, fed up, the parents decide that they’ll give the pessimist gifts so wonderful he can’t possibly be unhappy, and the optimist a gift so awful he can’t possibly be positive about it. Birthday morning, they send the pessimist to a room filled with all the best and most desirable toys, and the optimist to a room filled with horse shit.

They wait a bit, and then go to the pessimist. He’s sitting, sulking, in the middle of the room. They say, “But, why are you so unhappy?” And he says, “Because you gave me all this crap, and not what I really wanted.” They’re discouraged, but they go on to the other room, thinking, “He can’t possibly like horse shit.” They get there, and find the optimist cheerfully shovelling the horse shit out of the room. They ask, “What are you doing?” And he says, “With all this shit, there has to be a pony someplace.”

I’ve read a lot of self-help (some of it from as far back as the 17th century), and there’s often a pony, and I like the ponies. But there’s also a lot of horse shit. As it happens, I don’t need horse shit, but other people might be looking for manure, so they might find it useful. Or they might find ponies I didn’t notice. I’m grateful for self-help rhetoric.

Some of that shit, however, is toxic.

Self-help rhetoric has a structure. It says you have this problem, you’ve tried to solve this problem in various ways, and none of them have worked. It proposes a solution to the problem (the plan), shows how the plan will solve the problem, shows it’s feasible, and, ideally, argues that there won’t be unintended consequences worse than the problem it’s solving. In other words, it relies on the stock issues of policy argumentation.

I like policy argumentation, so I don’t think self-help rhetoric using that structure is a problem. Like any other discourse, it can be a problem depending on how the stock issues in policy argumentation are used. When self-help rhetoric is damaging, it tends to engage in shaming and/or fear-mongering in the need part. Often, it relies on identifying the problem as at least partially that we are bad people, or members of a bad group. It often says that the cause of the problem is a personal failing on our part and/or the machinations of a malevolent out-group. Thus, even though it isn’t necessarily political, it has a lot of qualities of demagoguery.

The plan they propose is to join their group, buy their product, pay for their advice. An important part of the argument for their plan is that they and only they or their product can solve our problem. They say the plan is feasible (is this policy practical) because you can pay in installments, or you just have to buy this one thing, read this one book, watch these free videos. They deal with stock issue of solvency (how will this plan solve the ill) in two ways. First, they provide testimonials, sometimes by representatives of the five percent (or less) that have succeeded (so far), or, second, by simply asserting that their group/plan/product will solve the problem if you commit with enough will.

Many of these ways of arguing are shared with discourses outside of self-help, and sometimes we argue one of these ways because it’s true. If our car’s brakes are failing, someone insisting that we might die if we don’t deal with this issue is not fear-mongering, and it may be that our options are limited. But it’s fairly rare that there is only one possible solution. There are many places that can fix our brakes, we might be able to take the bus for a while instead of driving, we might be able to borrow a car, or even buy a new one. So, one of the things that makes some self-help rhetoric toxic is that it says there is only one solution, and it’s the one they’re advocating.

Second, it says that, if this solution doesn’t work (and, honestly, I think every solution fails from time to time), it is our fault—we did it wrong, usually because of our inadequate will. So, there is no way that their plan/policy/product can be proven wrong because it can never fail; only you can. That evasion of accountability moves this whole discourse out of the rational, or even reasonable, and into the realm of a religious—perhaps even cult-like—way of thinking about the world. Because we failed, we have to recommit with greater effort and resources; we need to pay for another workshop, buy more products, perhaps even spend more time with other consumers of this product/members of this ideology. When it gets really toxic is when it says that we shouldn’t listen to any information that might weaken our resolve or make us doubt what we are being told.[1]

Just to be clear: what I’m saying is that the toxic kinds of self-help set you up for failure. And they set you up so that your failure will make you more dependent on the group/product.

It does this partially through appealing to the binary paired terms of good is to bad as pure is to mixed.

Good Pure Pride Determination

_____ :: _____ :: _____ :: ____________

Bad Mixed Shame “Doubt”

That we have this problem (procrastination, debt, low income) means that we are in the category of bad (the shaming part). The solution is for us to become good. If we want to be good, we need to think in absolute terms, with absolute (i.e., pure) commitment, cleansing our thinking of nuance, uncertainty, doubt, purifying our world of bad influences who might encourage us to doubt. We need to commit to this one group or one policy, and stick with it regardless of whether it works because, if it didn’t work, it’s our fault for not believing in it enough. In toxic discourses, purity becomes about opting for commitment rather than consideration. They say that we need to believe rather than think.

Far too much of our public (and even private) discourse about policy issues is the toxic kind of self-help rhetoric.

[1] Thus, as far as what makes something a pony is self-help rhetoric that is clearly presented as one way of doing things, doesn’t frame the issue as Good v. Evil, doesn’t promise its solution as one that will always work, avoids shaming, sets out reasonable expectations, recommends practices/products from which it doesn’t profit (or even benefit), can often be combined with advice/practices from elsewhere, and doesn’t present deeper commitment (more purchases) as the only possible response to setbacks or failure.

I often say that we should try to find the best opposition arguments, and so, when I’m trying to do that, there are some sites I tend to use. I wanted to post something about my sources, and then found I needed a fairly long explanation as to why I use these when I’m looking for the strongest argument for a policy, practice, or claim I think is wrong. There are two things I’m not doing–I’m not looking for “objective” or “unbiased” sources; I’m not looking for a representative sample from places along a continuum of party affiliation.

As I’ve argued, I think the left-right binary/continuum is nonsense (to the extent that it isn’t demagogically self-fulfilling), as is the notion of a binary of “objectivity” or “bias.” People who use terms like “objective” or “biased” can’t define them in a way that fits with research on cognition, and those terms are usually just what Burke called “ultimate terms.” A source might be very “biased,” in the sense of only including data that supports its argument, and yet all that data might be “objectively” true (that is, accurate representations of good studies and so on). I don’t think there’s any point in trying to find better ways to define objectivity or bias–I think we should just walk away from trying to find objective or unbiased sources, in service of a different goal.

A lot of discussion about sources is in service of the aspiration of The One Source on which we can rely. We have to abandon the comfortable fantasy of a source on which we can rely, a prophet with direct relation to The Truth. We all want clarity; we all want a source, author, ideology, perspective, in-group that guarantees us that what we believe is absolutely true. We all want to be able to believe rather than think. We are all suckers.

The fantasy of an objective source is unfortunately favorable to toxic populism in that both posit that there is some one perspective from which we might look at an issue that is the purely true one. Both rely on the false notion that, when we’re faced with deep disagreement, we should try to identify the group that has the Truth. If we find and join that group, then we will always be right, and we don’t have to think, but believe. Down that road lies demagoguery. If we believe that belief is enough, that there is an in-group that has a direct line to Truth, then we look for that group. And then we believe that only that (our) in-group has a legitimate policy agenda, and everyone else is spit from the bowels of Satan. And we start thinking that authoritarianism is a pretty good idea.

We all want to believe that our beliefs and behaviors are not just right, but the only possible way to think or behave. We pant after certainty the way my dog pants after squirrels. The difference is that he knows he hasn’t caught the squirrel, and we think we have.

If fyc, or any course, is to be a course in civics, then it means a course that teaches students how to recognize and resist that panting hope that, when we use this source, are a member of this group, (or whatever), we no longer have to worry that we might be wrong. We don’t need a course that tells us how to recognize when they are wrong, but when we are.

We shouldn’t worry that we might be wrong. That’s like worrying that water runs downhill. It does. We are. Just as, if we’re building a house, we have to take into account that water runs downhill, and plan for how we will manage rainwater, so we should acknowledge that we are always, if not actively wrong, then at least not seeing a situation from every possible point of view. We should also acknowledge that we, being human, think about the world through the lenses of cognitive biases. That water runs downhill doesn’t mean we have to lie on the ground and refuse to build a house; that we are all operating via cognitive biases doesn’t mean we have to lie on the ground and refuse to deliberate. There are ways that we can reduce the chances we’re wrong, and one of the most available and most straightforward, is to look at the best arguments that say we’re wrong.

If we believe that people disagree because we really disagree, (and not because everyone else is a benighted tool of a malevolent force) then we start looking for why people disagree. And it might be that some of the people who disagree with us are fools, stooges, psychopaths, or grifters–in fact, I think that it’s a given regardless of the issue and regardless of our position that some people on every point on the political spectrum are fools, tools, and so on (including us, from time to time)–but not everyone who disagrees with us is in one of those categories. And not everyone who agrees with us is an angel of enlightened and compassionate discernment. Because there are never just two sides to an issue.

And that’s why we need to find the best arguments that criticize our position, or argue for a policy we think is wrong-headed. Sometimes, we will find that even the best argument for some policy or candidate is incoherent, made in bad faith, profoundly dishonest, or not even good enough to be proven wrong. Not all arguments are equally good.

And this is where policy argumentation is a useful heuristic. If people are making a specific affirmative case for a policy we think is wrong-headed, and we read the best case for it, and it is wrong-headed, that doesn’t mean that our policy is right. Someone’s affirmative case (the plan for which they’re arguing) might be bad, and yet their negative case (what’s wrong with our plan) might be good. It also doesn’t mean that everyone who disagrees with us is wrong.

In my experience, we’ll often find that there are reasons and good enough arguments for positions, practices, ideologies, and groups other than ours. And, in my experience, we’ll often decide that, even though there are good enough arguments for a position, we still disagree. They’re good enough to be taken seriously, but not good enough to persuade us to change our mind.

What matters for the purpose of finding strong opposition arguments is: 1) if the source accurately represents the data (even if it is selective); and 2) if it is the best argument for that perspective.

I don’t think there is a two-dimensional way to represent our policy affiliations, so I talk about a spectrum. But even the metaphor of perspective is damagingly reductive. There are continua, but more than three, and some of those continua have more than one axis. I think it can be useful to talk about left v. right on some of those specific axes (e.g., social safety net), but not on all.

Here are what I think are some of the important axes in politics:

• Government regulation that promotes particular industries ( “pro-business government intervention”) v. free market [note that both of these positions would be considered “right-wing’]

• Government regulation that promotes safe, equitable, and ethical working conditions v. free market

• Government regulation that promotes safe, equitable, and ethical working conditions v. pro-business government intervention

• Interventionist foreign policy (intervention long before imminent existential threat) v. isolationism/pacifism (military action only for imminent existential threat)

• Interventionist foreign policy for purposes of promoting US businesses/economy v. interventionist foreign policy for ethical/moral goals (Wilsonian foreign policy)

• Support for a social safety net

• Epistemic libertarianism/authoritarianism: the extent to which someone believes that other points of view are legitimate points of view that should be heard; or, to put it another way, the extent to which people believe that there is an obviously good policy solution for every problem, and they know what it is

• Populism v. Pluralism: the extent to which one believes that there is one group that is real v. multiple legitimate points of view

• Populist Authoritarianism v. fairness: there is one group that is real, and all policies and practices should privilege that group v. procedural fairness

• Procedural fairness v. equity

• Regulations promoting reactionary v. progressive standards of “moral” behavior

• Naïve realist, reactionary, and demagogic hermeneutics of foundational texts (the US Constitution, Scripture, and so on) v. ….well, all others.

There are probably other important ways of thinking about various American policy preferences–this isn’t an exhaustive list. I just wanted to show that we really don’t have a binary of policy options or affiliations. I’m sure other folks could come up with lots of additional one (e.g., promoting environmental protection through nudges v. punitive regulation).

If we want, as teachers of argumentation, to get students to understand that our political world is not an existential and apocalyptic battle between Us and Them, then one way is to teach them how nuanced our policy commitments are—that they aren’t a binary or continuum. Just to be clear: there are people who want to destroy democracy and create a one-party state of people who have the pure ideological commitment. But those people are all over the political spectrum, and not everyone who disagrees with us is like that.

So, having said all that and given lots of caveats, here’s a list off the top of my head of sources I often use. I’ve given annotations on some, but not all. Again, my point is not to present this list as the definitive list that others should use, but to show what such a list might look like. Most teachers probably need to create their own, depending on their paper topics. For instance, if I had a lot of students writing about immigration, the list would be really different. A lot of sources on this list would be irrelevant, and I’d include some pro-union/anti-immigration sources, as well as some much more pro-immigration sources than anything I have on here. This list is intended to help others think about what lists they might give their students.

American Enterprise Institute. Reliably pro-GOP.

Cato Institute. Libertarian, reactionary.

Christianity Today. Conservative and moderate American Protestant Christian, conservative on social issues.

Council on Foreign Relations. Mixed.

The Economist. “Liberal” in the British sense.

Foreign Affairs. Interventionist, especially for business or military purposes, tends to be anti-Dem (but not always pro-GOP).

Foreign Policy. Interventionist for humanitarian purposes, tends to be pro-Dem (but not anti-GOP).

Guttmacher Institute. Reliable data on reproductive issues, generally pro-birth control, but not in ways that seem to bias the data.

Heritage Foundation. Almost always pro-GOP. Originalist on constitution. [Edited to add: I’m no longer recommending Heritage. They’re engaged in active dishonesty about CRT. If they’ll lie about that, they’ll lie about anything.]

Homeland Security. Government statistics on issues of immigration.

The Nation. Democratic socialist on economic issues, left on cultural/social issues, anti-interventionist on foreign policy, anti-GOP, often anti-DNC.

New York Times. Mixed economy on domestic, Wilsonian Foreign Policy, often anti-GOP and DNC (news articles strong, editorials problematic).

Pew Research Center. Reliable polling on various issues, transparent about methods.

Public Religion Research Institute. Reliable polling on issues of US religion.

Southern Poverty Law Center. Reliable information on hate groups of various political agenda, left on social/cultural issues.

Texas Observer. Specific to Texas, pro-immigration, social justice, equity, pluralist. (Texas Tribune is similar, but strives to be bi-partisan)

Wall Street Journal. Pro-government intervention for business/stock market in terms of both domestic and foreign policies; generally anti-Dem (news articles strong, editorials problematic).

Washington Post. Mixed economy on domestic, generally pro-Dem unless it bleeds, mixed on foreign policy (news articles strong, editorials problematic).