When I was working on the demagoguery book, I wanted to include pieces all over the political spectrum, including something by an author I really liked (Muir) and something from the radical left. Length made me cut the discussion of Muir’s “Hetch Hetchy Valley.” (At the time, I thought it would be part of my next book project. It’s now moved to the one after this at the earliest.) And I also spent some time thinking I’d write about the Weathermen, but writing about their rhetoric is really hard for a bunch of interesting reasons. Since I didn’t get to write about it in the book, I’ll blather about it here. I still think rhetoric from groups like the Weathermen should be talked about more in our scholarship and teaching for several reasons. But it’s tough.

First, their writings, especially Prairie Fire (1974), are mind-numbing in a kind of interesting way (so this is a reason for and against writing about them). That may be a deliberate rhetorical choice. It might be what used to be called mystagoguery, in which the rhetoric is basically unintelligible, but it seems smart, and the fact that the audience can’t follow the argument is taken to mean that the author is sooo smart, a prophet with direct connection to the Truth that the audience doesn’t have (but might get by putting all their faith in the prophet). A lot of New Age self-help rhetoric works this way, as do most conspiracy theories.

The term mystagoguery quickly fell out of favor among scholars because the accusation of mystagoguery was so often just anti-intellectualism or an unconsidered hostility to specialist discourse. The problem was that people called something mystagoguery (especially literary theory) simply because they didn’t understand it. But something not making sense to a particular person doesn’t mean it’s unintelligible in general. Early Habermas made no sense to me for a long time because I didn’t understand the references, context, counter-arguments, and terms. Once I took the time to try to understand them, it made sense. I can’t follow an argument about super-string theory to save my life, but it isn’t mystagoguery—I’m just not in the audience. So, to argue that something is mystagoguery requires first engaging in the most charitable reading possible—trying to make sure one understands the references and so on–, and then explaining why, even in that context and so on the text doesn’t make sense.

Arguing that Prairie Fire is mystagoguery would require going deep into the specific kind of Maoist Marxist discourse of the Weathermen, and then either showing that it didn’t make sense, or that their use of it didn’t make sense. That’s a long slog I didn’t feel like making.

To claim something is mystagoguery is to attribute a fairly specific relationship between the rhetor and audience. The audience isn’t persuaded of the arguments made in the text, because the audience can’t even say exactly what those arguments are (let alone explain what many of the terms or phrases mean), but they can get a general gist (capitalism = bad; weathermen = good), and they believe that the rhetor does understand everything they are saying. So, the audience believes there is a very clear set of arguments and the rhetor is a genius who understands them.

In another kind of discourse, however, neither the rhetor nor audience believes that there is a set of comprehensible claims logically related to one another. The claims might be clear to the reader in isolation, but their relationship to one another is nonsense. Much Weatherman rhetoric, for instance, lists various ways that different groups are oppressed by American capitalism, and makes claims about what a revolution would do, and why now is the moment that various oppressed groups will see their shared oppression, rise up together, and overthrow capitalism in favor of a communist society. There isn’t any argumentation showing the connections among the claims, and those connections are vexed.

The notion that the white working class would, any minute now, realize that their interests were the same as BIPOC (all of whom have the same interests), environmentalists, prisoners, gays, Palestinians, women, and every other group mentioned in the pamphlet seems to me implausible. Although it was doctrine in some (not all) Marxist circles that the first step in revolution was a massive coalition of people who had realized their shared oppression, that wasn’t how any revolution had happened. But Prairie Fire, like a lot of demagoguery, argues through assertion, not argumentation. There are specifics and data, but the specific cases described function to exemplify the point being made, not as minor premises logically connected to a valid major premise.

In other words, there’s a different kind of rhetoric going on here, discourse that is fundamentally epideictic but with all the discursive surface markers of argumentation. It looks like argumentation, but it isn’t. That’s interesting.

Another aspect of Weathermen rhetoric that’s interesting for scholars and teachers of rhetoric is the question of effectiveness. At the time of Prairie Fire (1974), there were authors engaged in Marxist critiques of American education, carceral system, economy that, whether we agree with them or not, were engaged in argumentation, and they did change minds. People did read, for instance, Angela Davis on the prison system and change their mind about it. It’s hard to imagine that anyone would read Prairie Fire and have their mind changed about abolition, China, Palestine, the Rosenbergs, or the other sometimes apparently random topics discussed. But, the authors might not have been trying to persuade their audience about those issues.

Prairie Fire is a manifesto, and one of the major rhetorical functions of a manifesto is persuading an audience somewhat committed to the cause to become fully committed. Augustine famously said that a sermon might inform pagans about Christianity, persuade Christians to believe correct doctrine, and convince committed Christians to walk the walk (not his exact words). A manifesto tries to convince believers to become beleevers, largely by trying to persuade them that the group is fully committed to success, and will be effective because it’s in a tradition of successful social movements.

It doesn’t make that latter argument through a careful comparison of strategies, but by providing a geneaology in which Weather Underground is placed at the end of a narrative that includes Harriet Tubman, unions, Toussaint L’O[u]verture, and others whose precise relationship to the Weathermen is never clearly explained. But I think the implication that one is supposed to draw is associative, and not logical. And that’s interesting.

There’s one other point I want to make about effectiveness. It’s hard to find a good secondary on the Weathermen—some of the histories make them heroes and others villains, with very little in between. All the authors seem to have an axe to grind. The people who were involved in it are not necessarily motivated to be entirely honest about their reasons for joining the group. Still and all, there’s some indication that, at least for some people, it was the sex and drugs. So, did the verbal rhetoric even need to be plausible, let alone persuasive?

The main reason I really wanted to write about the rhetoric of Prairie Fire is that its rhetorical approach—accumulation, association, assertion, dismissal of any opposition or criticism through motivism—might be connected to the epistemological premises of a certain kind of Marxism that was popular in that era: a kind of enlightened and omniscient naïve realism.

Naïve realism says that the world is as it appears, and that, if we get back to direct perception (which is relatively easy for sensible people to do) then we will all see the same thing: the truth. Disagreement is necessarily a sign that someone is biased and their views should be dismissed.

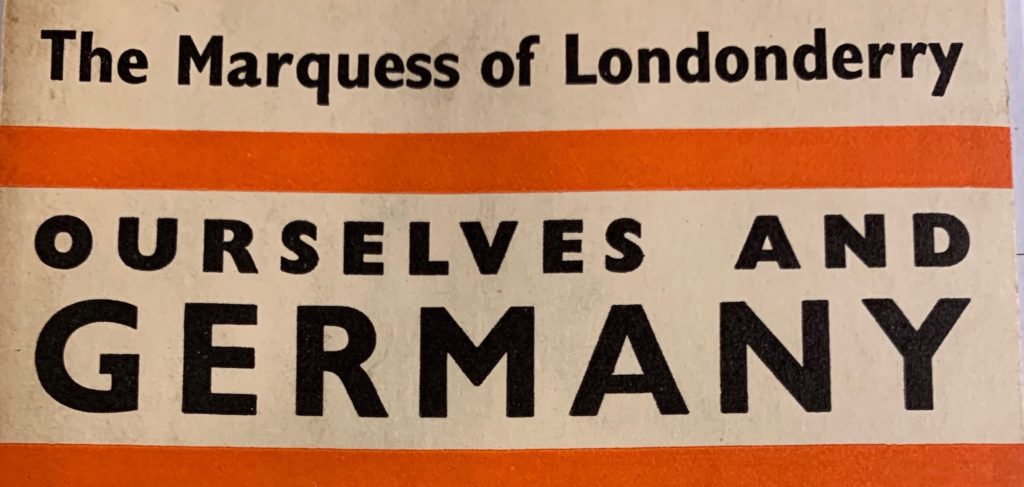

There is also a kind of naïve realism that says that only some people (those who have been enlightened) can have that unmediated perception of the truth, and that their perception is universally valid—they are omniscient. This way of thinking about thinking is deeply anti-democratic, and yet common in democracies. It isn’t particular to democracies, nor is it specific to any one political affiliation.

There are four important assumptions involved in the enlightened and omniscient naïve realism model of identity and perception: 1) that there is a truth in any situation—a true way of thinking about religion, the truly best policy, a true narrative about a historical event; 2) a single individual can perceive this truth (that is, they can have a perspective-free, omniscient viewpoint, from which they can see everything that is true about poverty, the Trinity, WWI); 3) certain experiences (a particular kind of education, a conversion experience, success in business, military prowess) and/or group identity (wealthy, poor, GOP, Dem, white, young, old, so on) have either given them or signify their enlightened and omniscient naïve realism; 4) because their point of view is omniscient, everyone who disagrees with them is biased (by cupidity or stupidity), limited to one perspective (seeing only part of the situation), or lying (they know what the truth is, but it’s inconvenient, risky, or unpleasant, so they deliberately or choose the obviously wrong policy).

The political implications are pretty clear: there is one right policy solution to every problem. There is no such thing as intelligent and informed good faith disagreement. That one right solution is obvious to the right people, so disagreement is itself a reason to ban someone from the discussion, and to keep political power limited to the people who demonstrate enlightened omniscience. In other words, it’s anti-democratic. There may be forms and norms that appear democratic–the communist bloc nations had constitutions and Bills of Rights, and Massachusetts Bay Colony claimed to support “freedom of conscience.” But, in all those cases, people had the right to be right–that is, the right to agree and not the right to disagree.[1]

Ultimately, enlightened omniscient naive realism ends up in a tyranny of some form, perhaps a one-party state (such as Dinesh D’Souza advocates), a theocracy, herrrenvolk democracy, oligarchy, and so on.

In the case of the Weathermen, it ended up with their being racist, and that’s another interesting aspect of them. Because they were enlightened by virtue of their ideology, they saw themselves as better judges of the conditions of Black Americans than Black Americans, with the obvious consequence that they became notorious for whitesplaining. Their epistemology undermined their sincere attempts to be anti-racist.

Participating in politics is, as Hannah Arendt elegantly argued, a transcendental leap into uncertainty. We can reduce the uncertainty of any particular leap by using processes that reduce our reliance on cognitive biases, such as trying to find the smartest opposition arguments we can, trying to think about what evidence would cause us to change our mind, and making a distinction between agreeing with an argument and thinking it’s reasonable. Believing that there is only one right policy, and that we happen to know it is like making that leap without a rope, parachute, rescue plan, or map.

[1] When I make this argument, sometimes people think I’m arguing against vehemence, and I’m not. I think it’s great for people to be passionately committed to their argument. Being passionately committed to our argument, and arguing vehemently that someone else’s argument is wrong because their evidence is flawed, they’re missing important information, their sources are bad, and so on—that’s what democracy needs to be. Arguing that one’s preferred policy is the best is how people are likely to argue. But arguing that one’s preferred policy is the only possibility, and that every single other policy is obviously wrong, and obviously every single person who disagrees is a benighted, biased, corrupt, bigoted fool—that’s profoundly anti-democratic. Dismissing arguments because everyone not in the in-group has bad motives is the problem. It’s also false. None of us is actually the person who crawled out of Plato’s cave and sees the truth in every situation.