Why do some Libertarians have so much trouble with the concept of systemic/institutional racism?

Why can people who believe complicated conspiracy theories not believe that a little bit of racism on the part of a lot of people adds up to a lot of racism? Why can people who believe that government regulations are oppressive refuse to think that oppression might have valences? Why can people who believe that big institutions do everything wrong not think that they might also get issues of race wrong?

The contradiction is particularly troubling when it comes to Libertarians, since, in my experience, they strive to be consistent and logical in how their policies relate to their beliefs (unlike, for instance, Trump supporters). And Reason talks about institutional racism as a problem, so it isn’t that Libertarianism is essentially hostile to recognizing institutional racism.

Libertarians say that the basis of their belief is that individuals should be fully free in order to achieve what they can. Obviously, a person born into poverty isn’t as free in terms of the possible achievements as someone born into wealth. So, were Libertarians genuinely committed to a notion of a system that made sure all individuals are equally free, they would fully support systems that levelled the playing-field, so to speak, of the rich and poor, the abled and disabled, the stigmatized and the privileged.

In this post, I want to talk about the Libertarians who refuse to support such policies, and that isn’t all of them (in other words, #notallLibertarians).

These Libertarians like the strictures of birth that make sure the game is rigged, but they don’t like the strictures of government that try to make sure that individuals are free to achieve their best. They don’t want a fully free system, in which all people are equally free to achieve all things; they want a system in which they can thrive without restriction. They argue that help from the government creates dependency, while accepting the help they’ve gotten from their birth hasn’t. That doesn’t make sense. If accepting help creates dependency, then they’re dependent on their birth.

I have spent a non-trivial amount of time arguing with this kind of Libertarian, and my experience is that their entire way of arguing makes no sense unless you assume the just world model, and engage in a non-trivial amount of “no true Scotsman.” When pushed on the point that they can’t actually defend their position, they start the whaddaboutism. I’ve also never met a Libertarian who knew much of anything about the economic history of the nineteenth century, but that’s a different crank theory.

I like Libertarians. In my experience, they’re logical af. Thus, unlike people on various other points on the political spectrum (it isn’t a binary or continuum), most of them are consistent regarding their major premises. They follow their arguments out. I admire that. They take unpopular positions because those positions logically follow from the premises they value. They reason deductively.

That they are true to their principles makes them very different from a lot of people with whom I argue, and I think they should praised for that consistency. The problem is that some Libertarians reason from the premise that all individuals should be equally free to achieve, while some reason deductively from the just world model and faith in the will. Let’s call this latter kind of Libertarian Just World Libertarians.[1]

The “just world model” says that people, products, and ideas that are good will succeed. As a corollary, the most successful people, products, and ideas are the best.

The “just world model” is one of those models not smart enough to be wrong. Its adherents (they’re all over the ideological spectrum) can find data to support the just world model, but arguing with them always reminds me of Catholic arguments for the virgin birth (involving parrots and light through glass). They refuse to name the data that would prove them wrong. The just world model supportable, but non-falsifiable. They almost always end up in the “no true Scotsman” fallacy or Gnosticism.

There is an old joke: someone says, “All Scots like haggis,” and Joe says, “I’m a Scotsman, and I don’t like haggis,” and the person responds, “You don’t count. You aren’t a true Scotsman.” That’s how the “just world model” works—it’s an Escher argument, in which each claim disappears into the premise that can’t be falsified.

The second non-falsifiable principle to which Just World Libertarians are committed is that if an individual wants something badly enough, they can get it. It’s still “no true Scotsman” because an individual who doesn’t achieve their goals can be dismissed as not having enough will.

Libertarians are far from alone in reasoning about politics in this way—they have premises that they refuse to consider rationally. Were I Queen of the Universe, I would dictate that instead of talking about a binary or continuum of left or right, we would map the spectrum of political affiliations in terms of how people reason about politics, rather than what their politics are. Thus, people who refuse to look at disconfirming data, read opposition information, or identify what would make them change their mind would all be grouped together, regardless of how they vote. Unhappily, I am not Queen of the Universe.

What matters in a democracy isn’t what your political affiliations are. Democracies can manage a lot of very different political affiliations. What matters is our commitment to democracy. It doesn’t matter if media would say that you’re “left” or “right” or “centrist.” If you aspire to a one-party state, if you think your policy agenda is obviously right and people only disagree with you because they’re deluded or corrupt, if you refuse to look at information that contradicts what you believe, if you don’t worry about whether your argument is rational, you’re opposed to democracy.

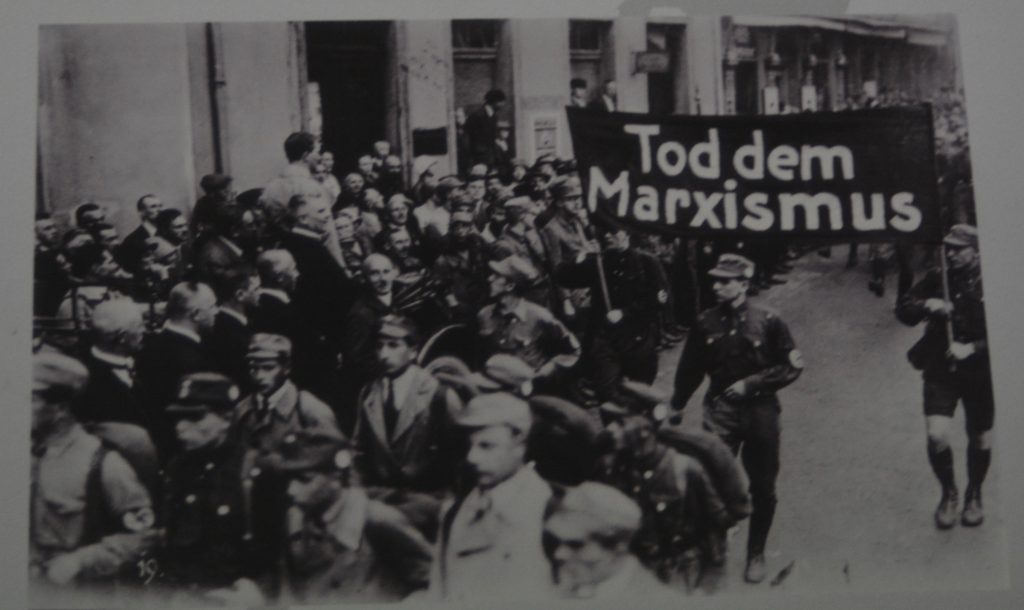

The two premises of Just World Libertarianism—people get what they deserve, and an individual can achieve whatever he wants with sufficient will (the gendered pronoun is deliberate)—are confounded by African-American men being stopped more often, searched more often, charged more often, and getting harsher penalties than white men. If our system doesn’t treat African American men in the same way it treats white men, and therefore African-American men are not equally able to achieve whatever they want, then the major premises of Just World Libertarianism are wrong.

And they are. Racism isn’t the consequence of individuals who deliberately choose to engage in racist actions out of hate or fear. Racism is a system that ensures that people of variously imagined stigmatized “races” are held to different standards from others, given diminished options, and perceived as deserving their diminished status because that they have a diminished status is proof that they are worse.

And that’s why Just World Libertarianism is racist. The adherents of that ideology are, in my experience, non-falsifiably committed to exactly the premises that fuel institutional racism. Of course, it isn’t only Just World Libertarians who are irrationally committed to the just world model and faith in the will—so are American fundagelicals.

And that is why fundagelicals fling themselves around like over-tired two-year olds when anyone talks about institutional racism: because if institutional racism is a plausible explanation about how the world works, then the basic premises of their political agenda are flawed. It is, and they are. And they’re racist.

[1] In my experience, the self-described Libertarians who consistently vote GOP are in this latter category. So I suppose someone could say, “Not real Libertarians.”