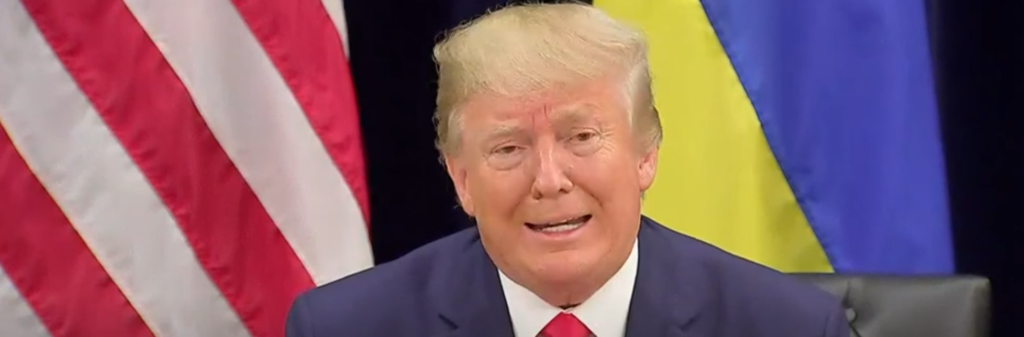

I mentioned elsewhere that it’s hard to argue with Trump supporters[1] because many of them have openly embraced having a political position that is rationally indefensible, and they are proud of it. Supporting Trump was rarely the consequence of rational argumentation (as far as I can tell they stopped trying to support him through rational argumentation over a year ago) but it now seems that openly admitting their commitment to blinkered loyalty is considered a virtue. I said, for those reasons, it’s a reasonable strategy to refuse to argue with them at all. But, someone asked me, what if you want to?

I think it’s useful to start with explaining why it’s so hard to argue with them. In my experience, at least for the last two years, Trump supporters have simply been repeating talking points they’re hearing in various places (which is why they sound so much alike). There are two different kinds: the “haha we’re winning” response (which is more or less an admission that they have no rational argument for supporting him); talking points that look like rational argumentation but are neither rational nor argumentation. I think a lot of those talking points have been created by people who are consciously designing talking points that feel good to repeat, and that confound the libs. And it’s true that a lot of the arguments are hard to refute, but that’s just because they don’t actually make any sense.

It’s as though we are playing chess at your house, and I beat all the pieces into little bits with a hammer, set your house on fire, and then declare myself the winner. While it’s sort of true that you can’t respond to what I’ve done with a chess move, that doesn’t mean I won the chess match.

And what does it mean to “win” a political argument by refusing to engage in argumentation? Perhaps a more apt analogy would be if we were disagreeing about whether a building was fire safe, and I denied there was such a thing as fires, said you’re responsible for all the fires anyway so the solution is to ignore you, and insisted that fire hoses just transport water and so do straws and therefore we can prevent fires by throwing straws all over the place. You would have a very difficult time proving me “wrong” (especially about whether you’re really responsible for fires), not because my arguments are so good, but because they’re so bad.

I think they’re deliberately bad because it’s actually harder to refute really bad arguments–you end up having to explain how argument is supposed to work.

That will take me several posts to explain, and it’s easier to explain if I give examples, so let’s imagine Random Internetasshole (call him Rando) and Chester are arguing about something. In general, Rando’s strategy is to make a bunch of absurd and unsourced assertions and then, when pushed to defend them (or even make them coherent), he deflects. Rando’s whole strategy is to keep the disagreement away from his argument—to try to make Chester support claims, provide sources, and generally behave like the adult in the room. Rando has to keep attention away from his argument because he’s trying to pretend it’s a good one, and it’s actually a big hot stinking pile of shit. Rando has to keep attention off of how bad his argument is by shifting to Chester the burden of showing it’s a bad argument rather than Rando’s taking on the responsibility of showing it’s a good argument. That’s how Trump supporters argue.

So, if you want the short version of these many posts, the best strategy is to keep the burden of proof on Rando. Insist he show he has a good argument. He’ll resist like a cat being put into a bath because he doesn’t have a good argument, and he doesn’t know how to defend the claims he’s loyally repeating—his talking points didn’t include that page. He’ll deflect.

I’ve often wondered (when arguing with some people) why they’re trying to engage in argument at all, since they’re just making themselves look stupid to people who understand how argument works. I think the argument about replacing RBG is going to bring out the worst aspects of their already bad ways of arguing because it’s pure Machiavellianism (any and all means are good if they lead to the success of the Trump Administration). Machiavellianism is, by its nature, never rational argumentation. Rational argumentation says that there are standards that apply equally to all interlocutors. Machiavellianism says that no standards apply to us.

The rhetorical problem for Trump supporters is that a lot of them don’t like thinking of themselves as irrationally supporting a Machiavellian Administration. So, they talk as though their political agenda is grounded in consistent principles and can be defended through rational argumentation, but neither is true. That contradiction (an unprincipled policy agenda indefensible through rational argumentation) is the handful of steaming shit from which the talking points are supposed to distract us.

Briefly, here’s how the current pro-Trump talking points work (or don’t):

• they claim that each political action is driven by a principle that would appear to transcend faction, but they appeal to contradictory principles (for instance, elections that the GOP wins are mandates from the people about how Congress should behave, but elections they lose aren’t—so there isn’t really a principle about elections being mandates).

• they justify this Machiavellianism by saying that they are committed to a higher principle, but it gets weird when they try to articulate that “higher principle”—they aren’t committed to small government, anti-corruption, law and order on principle (they’re fine with big government if it’s surveillance of Trump critics, Trump’s grifting the government, police forces above the law). So, they like to think of themselves as “principled” but what they mean by that is inflexible loyalty to the group.

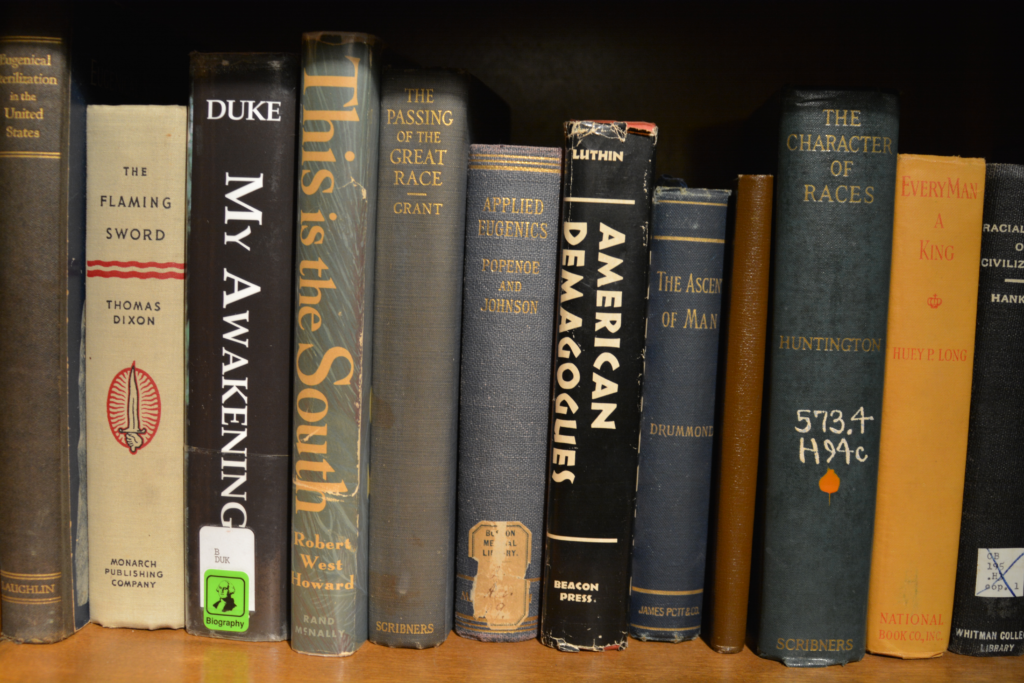

• because, I think, even they feel some cognitive dissonance (many of them claim to follow someone who said, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” after all), they have invented the hobgoblin of abortion in the hopes of making it the principle to which they are committed. Criminalizing abortion is not a rational strategy for ending abortions (oddly enough, many of these same people believe that criminalizing activity doesn’t reduce it when it comes to gun violence—they advocate praying away gun violence, but they want to ban abortion), and they refuse to do the things that would reduce abortion. It doesn’t end abortion—it just ends safe ones —and it isn’t the most effective strategy for reducing them. [2]

• they believe that criminalizing abortion makes them good people, and therefore anything they do is justified. In other words, they’re Machiavellian. (Thus, every argument, if it goes on, will have them say at some point, “Well, Dems are pro-abortion” when Dems have a better plan for reducing abortion than they do).

• except they aren’t principled (see the first).

• in other words, they are proud that they will make any argument or use any tactic to get their way because they are rigidly committed to what they think of as a principle (they want to criminalize abortion), and yet they want the legitimacy of making a rational argument in support. (And just to be clear, they don’t even have a rational argument when it comes to abortion—it’s all ethical theatre.)

• or they reject argumentation entirely and just want to win, and they think they are.

The final point I’ll make is that this is all profoundly anti-democratic. Many of his supporters openly want a democracy of the believers—that is, a “democracy” in name only, in which only people who agree with them get to hold power, influence decisions, or vote.[3]

Again, since none of this adds up to a rational argument, and Trump supporters have abandoned rational argumentation, a lot of people choose not to argue with them, and that’s fine. But someone asked, and so I wanted to write something about what to do if you do choose to argue with them. It’s turned into a long analysis of pseudo-rational argumentation (which is far from unique to Trump supporters), so that will be a series of posts much of which will repeat things lots of people have said (including me on this blog).

[1] I’m saying Trump supporters, and not Republicans or conservatives, because I think there is an odd (and even disturbing) conformity in Trump supporters’ arguments specifically—in my experience, they’re largely repeating the same arguments. I don’t see the same level of conformity among people who self-identify as conservative or Republican and aren’t especially supportive of Trump. (I don’t just mean Lincoln Project–some of whose arguments are non-rational at best–but a kind of person who isn’t in the Trump cult. What I haven’t watched enough is whether people in the Trump cult can make good arguments when they’re on topics other than Trump–that would be interesting to see.

[2] I think many political strategists don’t want to solve abortion because, if they did, they wouldn’t have it as a political rallying point. If they overturn Roe v Wade, they’ll have to find something else—a war on illegal abortions or attacks on birth control. Either of those will have unfortunate political consequences, since a lot of people do want access to birth control, and do want abortions for them and people like them.

[3] You find people like this all over the political spectrum—people who are eliminationist in their politics. I think it’s interesting that so many of these people are obsessed with sharia law–it’s clearly projection.