[Image from here]

This class is about how to argue whether a text or action of some kind is racist; this is not about going through the semester stamping things RACIST or NOT RACIST. That’s a waste of time, largely because it isn’t a neat binary between racist and non-racist things (there are degrees and kinds of racism). But it’s also a waste of time because it doesn’t get at why disagreements about racism get so ugly so fast. This class is about more useful ways to talk and think about race that should enable you to have better disagreements about racism.

One point that we’ll come back to again is that almost no one thinks they’re racist (I’ve never met a racist who said s/he was racist)—many people believe that as long as you don’t mention race, use a known racist term, feel and express active hostility to every member of any other race, then what you said/did can’t be racist. There are also people who say, “I can’t be racist, I’m married to a POC” or “I can’t be racist because I’m a member of [an ethnicity against which there has also been discrimination].”

Since they didn’t say the word race, let alone mention any specific race, and are not demonstrably racist against all non-white races, the person who called them racist is the one who “made this an issue about race,” and that makes the accuser the Real Racist Here. There are other assumptions that people make about what it means to be racist that, paradoxically, contribute to racism—such as thinking that racists know they’re racist, and intend to be racist; that racism is conscious hostility to every member of that race (so your black friend is a card you can pull out to show you aren’t racist); that there is only one kind of racism (what scholars call biological racism). There’s also the muddled notion that, since racism is bad, only bad people say or do racist things, if someone is accused of having done a racist thing, they can be exonerated by someone testifying that they are good people—they feed the homeless, they are nice to people, they have a POC as a friend.

That last point is important–that people falsely believe that the claim that someone has done something racist can be deflected by pointing out something good they’ve done–, and it’s where I want to start: what happens quickly in a discussion about racism is that, if you point out that you think I did something racist, I now see the issue (what we’ll call the stasis) of the argument as my identity as a good or bad person (a racist or non-racist), and so I start defending myself as a good person. Whether I am a good person has nothing to do with whether I’m racist—as you’ll see in this class, there have always been good people, many of whom were engaged in important anti-racist activity, who did racist things.

On the whole, I think Jay Smooth’s advice is really good—don’t argue about whether a person is racist, but whether that thing they did was racist. (Also, I love the term “rhetorical Bermuda triangle.”) After a while, if a person does a lot of racist things, I think it’s fair to conclude that they see everything in racist ways, and you can conclude they’re racist—but that’s probably also the moment you aren’t engaging with them anymore. (Or you’re engaging just long enough to ask them to pass the mashed potatoes.) People who are deeply embedded in persistently racist rhetoric are, in my experience, so deeply embedded in identity politics—the notion that the political and social worlds are both zero-sum battles between their “us” and all other groups (“them”) that they’re beyond rational argumentation. This class might help you understand them better, but it won’t help you persuade them because I think they’re beyond persuasion. With people like that, just change the subject or walk away. You can try to argue with them, but don’t keep your hopes high.

But that leaves a lot of people, including you and me, who inevitably do or say racist things, or, at least, things that someone thinks are racist, and who are in situations where we think someone else has done something racist and they probably don’t think they have, but are open to talking about it. This class is not about how we persuade overtly racist people to stop being racist, nor about how we prove we aren’t racist, but about how we talk about the muddled and gerfucked world in which actions, policies, texts, sayings, comments, and conversations might be usefully described as some degree of racist. This class is not about learning to put a stamp of racist or not racist on actions, texts, or people. It’s about trying to talk better about racism. It’s about the assumptions that keep us from having better discussions about racism.

Racism is one of those topics (like grammar, oddly enough—more on that in the class) on which everyone considers themselves an expert. Recently, I found myself in an argument with someone who, when I pointed out that his definition of “racism” didn’t fit with what scholars said about it, said, “Who are these ‘scholars’ of racism? Where are they?” I wanted to post that gif of someone clicking on google, but it would be google scholar. In any case, what matters is that he could have answered that question himself had he queried the topic via google scholar, but he didn’t. He didn’t because he thought racism was an issue about which every person is an expert (or, at least, everyone who agreed with him).

But there are scholars of racism (who agree that there are different kinds and degrees of racism) and the history of concepts of race (who agree that those concepts have changed over time, and they vary across cultures). We’ll read some of them. What scholarship about rhetoric brings to their work is an understanding of how people argue, and especially how people argue productively about definitions.

Different definitions of racism: the rhetorical triangle

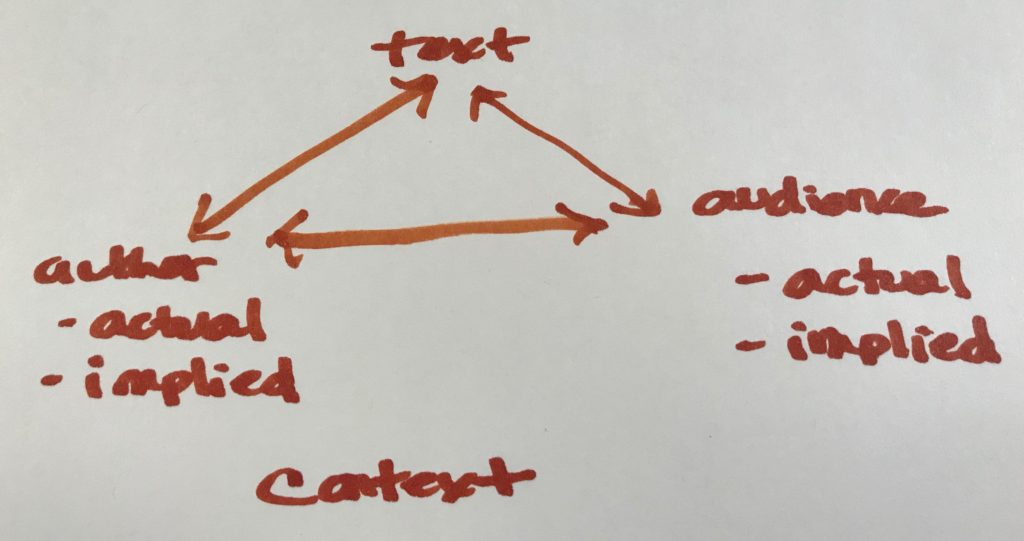

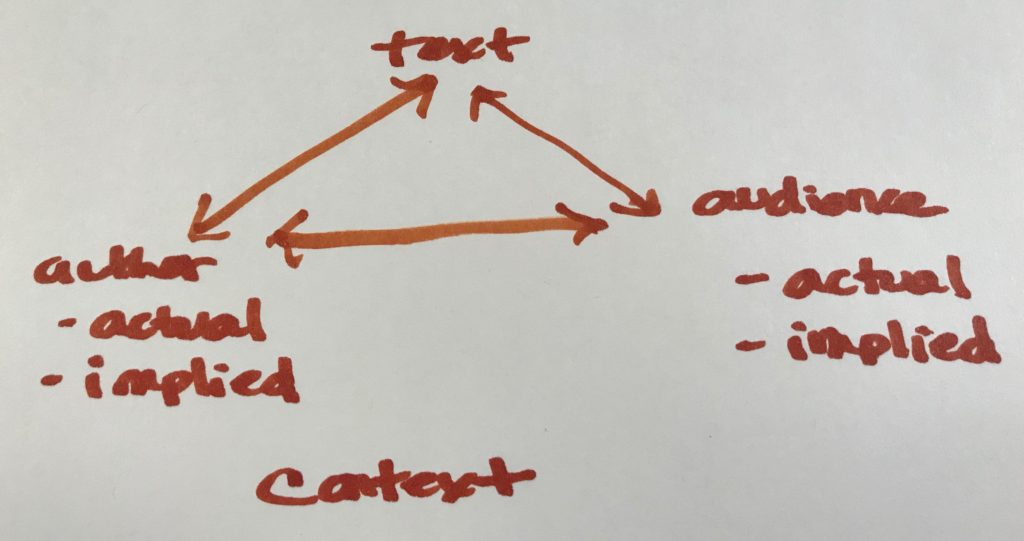

The first thing to understand about disagreements is that people in any disagreement engage in what’s called “motivated reasoning”: “motivated cognition refers to the unconscious tendency of individuals to fit their processing of information to conclusions that suit some end or goal.” One way to think about different definitions of racism is in terms of the rhetorical triangle—people will appeal to different points on the triangle as what constitutes racism.

The notion of the triangle is that a text is created by an author who has a conscious intent as to what impact that text should do to the audience, and it happens within a context. Thus, I am writing this text to try to explain racism to students in the class I’ll be teaching this fall. I’m writing this within the context of the course requirements and readings, and also the context of a President being accused of racism and our world one of increasing racially-motivated violence.

The rhetorical triangle is really simplistic. The situation is actually much more complicated than that—for instance, I make certain assumptions about students (what references you’ll get, what I’ll need to explain). You look at the assumptions I make and infer what kind of reader I think I have. That is the implied audience. Those assumptions might be wrong; they’ll inevitably be at least slightly wrong. A group of students is a “composite audience” (some of you know more than others, some won’t understand references, and some will find my explanations unnecessary). The actual readers of the text won’t match the implied audience. Similarly, there is a difference between who I really am and how I present myself in this text—the difference between actual and implied author.

This triangle doesn’t really do a good of modelling how texts are actually created, or how people are actually persuaded, but it is a good model of how people think communication works (what might be called “folk rhetorical theory”). And, so, people tend to use it (without even thinking) when trying to assess if someone said or did something racist. So, for instance, if we disagree as to whether Chester said something racist, here’s how that argument might wander around the points on the rhetorical triangle:

• Author: intent

This is the most common stasis for an argument about racism, and it’s often not actually relevant and very rarely useful. People often argue about whether an author consciously intended to say something s/he knew to be racist because the most popular understanding “racism” is that it is the conscious intent to hurt people of another race. I think there are two times that it’s useful to talk about intent, and one is figuring out what we do about it. People often use a term they don’t know is racist, cite a source they don’t realize it’s racist, engage in cultural appropriation when they think they’re honoring a culture, or otherwise do racist things that they wouldn’t have done if they had understood beforehand. But, in all those cases, the lack of intent doesn’t mean the racism disappears. It means the person apologizes and doesn’t do it again. The second way that the discussion of intent can be useful is if Chester sincerely believes he has been misunderstood—he was being sarcastic, for instance. (Dave Chappelle has said some really interesting things about his comedy routine in this light, and Oluo talks about this issue really nicely in her book.)

There are a lot of problems with making “intent” the stasis for arguing about racism. First, it means we aren’t talking about the most important and most damaging kinds of racism (structural, cultural, implicit bias). Second, we quickly get into the issue of motivism—of trying to guess someone’s motives. We’ll talk about both of those much more in the class.

• Author: actual

This stasis also seems sensible within the frame of racism as coming from deliberate intent, and it’s inevitable if we always decide that racists and not racism matter—that is, if we think that there is a binary of racist or not, and we’re trying to figure out whether the person is racist (as though that settles the question of whether the act/text was racist—it doesn’t). If racism is bad because racism is something only bad people do, then if we can figure out if a person is bad or not, we’ve settled the issue of whether they’re racist or not.

That’s like assuming that only bad people are bad drivers, so if you say I’ve driven badly, I could respond with evidence about other ways I’m a good person. Good people can be bad drivers. People can be good in many ways and still engage in, support, or enable racist practices.

• Author: implied

This stasis is pretty uncommon—I’ve only seen it when people are trying to figure out the intent of someone they don’t know, or whom they can’t really identify, or where there isn’t enough information (such as the question as to whether Edgar Allan Poe supported slavery), and so you have to rely on a single text or a few texts. It’s still about whether the person is racist.

• Text: word choice

My sense is that this stasis is in a tie with “actual author” for second most common. This stasis is on the issue of whether the text has the word “race” in it, or a racist epithet. If it doesn’t, then it can’t be racist.

This stasis is attractive to people who believe that things don’t exist till they’re said. These are the same people who, if Uncle Hubert says something racist, and cousin Chester says, “Hey, that’s racist,” that is when the conflict started—everything was fine till then. These people think that they can keep a child from being gay if they don’t let the child come out. There isn’t conflict till the conflict is named because nothing exists till it’s named. (MLK Jr. talks a lot about this, especially in “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and “Love, Law, and Civil Disobedience.)

One version of this is almost hilariously casuitical (that is, hair-splitting): that if a rhetor doesn’t mention race, but “culture,” then it isn’t racist. Until the rise of biological racism, “race” was always country of origin. Even after the rise of biological racism, there was a lot of “science” that showed that people from various countries (or continents) were inferior—the Irish, the Poles, the Italians–, biological racism never had a coherent biological definition of race. Some scholars use the term cultural racism, but I’m not wild about that term, since all racism is and always has been about country of origin (sometimes going back pretty far, as with Latinx whose families have been in the US far longer than Trump’s, or Native Americans who are oddly framed as not native to the US). The Jews are not a race.

Here are some questions to ask yourself: are people from Spain white? If two people from Spain move to Mexico and have a child (so that child is a Mexican citizen), is that child white? Are Germans white? If two Germans move to Mexico and have a child, is that child white?

Racism never is and never was actually about biological categories—it’s always about socially constructed categories we have that are entirely political, historical, and thoroughly cultural. Nazis claimed their categories were scientific, but “Jewish” is not a race. Harry Laughlin, the expert who advocated forced sterilization, and extremely restrictive immigration quotas for Poles, Croats, and, well, Eastern Europeans generally, argued that they were different races from the Irish and Italians (or something—his argument is more than a little hard to follow). Madison Grant, still influential among racists, insisted that there were three white races, and intermarriage among them was disastrous. His categories weren’t biological, but cultural, religious, linguistic, and whatever helped his argument (that is, motivated reasoning). In other words, as we’ll talk about in the class, making a “cultural” argument often, but not always, is a racist argument (it depends on whether the “cultural” qualities are naturalized).

Another way that the word choice stasis comes up (with overlaps with context and audience) is whether an author is using dog whistles. That issue is sometimes straightforward (“welfare queen”) but sometimes more complicated, as when there is a possibility of someone not knowing that something is a dog whistle (there was a funny letter to an advice column about an older colleague who was, apparently completely innocently, usimg the Pepe the Frog emoji in emails.).

• Text: argument

This stasis is on the question of whether an argument endorses policies or positions or beliefs that are, in consequence, racist. If you are advocating that some races are more intelligent than others, it doesn’t matter if you avoid “racist” terms—that’s a racist argument. David Duke, for instance, spends an entire book insisting he isn’t racist, while arguing that some races (his) are better than others in every way that matters. It doesn’t matter if he avoids the ‘n’ word. He’s racist. The text: argument is a really productive stasis, but it’s hard for a lot of people to grasp. A culture really concerned about racism would spend a lot of time on this stasis. We don’t.

• Text: tone

Another way that people defend racist arguments or policies as not racist is that they pay attention to tone. Too many people (falsely) assume that the problem with racism is that it is a feeling of hostility toward all members of another race (or toward all other races). They see racism as an expression of hate, and they assume you can’t hate someone without knowing it. It isn’t especially helpful to frame racism as a kind of hate; while there might often be some kind of aversion, racism is quite frequently grounded in condescension, in-group favoritism, erasure, nostalgia, fallacious universalizing, and other ways of thinking that don’t require active hate on the part of individuals. But, if people assume that racism is hate (something we get from movies, where racists are mustache-twirling hateful bigots who know they are bigots and know they hate others), then they assume it can only be expressed with a hateful tone. What you’ll see in this class is that a lot of people have advocated (and enacted) extraordinarily racist policies—including forced sterilization, race-based imprisonment, even genocide—with a calm, “scientific,” sometimes apparently compassionate tone.

• Text: source, format

This stasis doesn’t show up very often, and it can be productive—it can rarely settle the issue, but it can be relevant that an author has a long history of writing racist (or anti-racist) pieces, it’s from a press or journal with a long history of racist (or anti-racist) arguments. That information can help determine if something is satire. It’s also useful to look at sources—if an author is citing racist sources as though they are reliable (and not in order to make a point about their being racist)—then it’s probable that the argument is racist (so this is useful in conjunction with the argument stasis).

• Audience: implied

The implied audience (which some people call “intended” audience—it’s the kind of person the author appears to intend to reach—and others call the textual audience) is the kind of person implied by the various assumptions the author makes. You’ll do much better if you don’t identify the audience by social groups (e.g., students, teachers, white people) since you inevitably end up making generalizations about groups, many of which are false (so, for instance, Malcolm X wasn’t trying to appeal to “black people” with “The Ballot or the Bullet” since it’s an exclusively American argument, and not even all African Americans would agree with his premises). Try to identify an audience in terms of beliefs and assumptions, not identity.

Looking carefully at implied audience can help with disagreements about the argument. For instance, when we’re trying to figure out if an argument is racist we might need to decide if something is satirical, if an author is calling for violence or just engaged in hyperbole, if an author is serious or joking, if an author is repeating a racist claim because s/he endorses it or thinks it’s racist on its face. And trying to figure out that implied audience can help us do those things.

• Audience: actual

In this class, we’ll talk a lot about racism being a question of consequences, and so it’s useful to see how the audience responds (such as that Malcolm X’s audience laughs a lot, or commenters on a post don’t get it). If a text rouses an audience to racist violence, it’s reasonable to argue that it’s racist. Oddly enough, it doesn’t always work the other way—a text might be racist in argument and yet not in consequence because the audience has shifted, its rhetoric is incompetent, or various other reasons.

• Context

When people are arguing about racism, we often end up on the question of context—was that text racist in context (such as Ronald Reagan talking about “states’ rights” in Philadelphia, Mississippi; whether we should consider something racist if it was using language and arguments considered “normal” in the era; if the argument was progressive for its era or context). It’s perfectly possible for something to be not racist in one context and racist in another.

As is clear from the above, I think some stases are more productive than others, but I don’t want to sound as though there is only one right stasis. This list is mainly useful for you to understand why people are disagreeing—often you have one person arguing from the stasis of actual author (“I know Chester, and he is a good dog”) and someone else arguing from actual audience (“after that speech, his audience rioted, and attacked squirrels everywhere”). Being able to identify that they are arguing from different stases can mean that the discussion might move to a better place—you might argue, “I’m not saying that Chester is a bad dog, but I’m saying that speech reinforced the racism of the audience, and so he shouldn’t have made it.”

Also, it’s sometimes useful to argue that a text or action is racist from several different perspectives, or to note that someone is fully on the issue of actual author and the issue really is systemic racism. (We’ll talk about that more in class.)

The other point I want to make here is that we often want to make every bad action racism, and that isn’t always helpful (or accurate) for various reasons. Sometimes it is productive to stay off of the racism argument entirely, and just argue that the person is a jerk or the action was terrible.

Different kinds of racism

You’ll read a lot of things this semester that argue for different ways of dividing up kinds of racism. So, when you argue that people disagree about whether This Text is racist (paper #3), and you want to say that one person is assuming that all racism is biological and the other side is cultural, you’ll want to cite specific sources for your definition (such as the Encyclopedia of Race and Racism).

Racism is an instance of in-group favoritism—the tendency to think that members of your in-group are entitled to more than members of out-groups; that in-group members have good motives, and out-group members have bad motives; that the world (or your nation, culture, community) would be better were it only in-group members; that most of our problems are caused by the out-group; that the in- and out-groups shouldn’t be held to the same standards.

So, for instance, I live in an area that has a lot of cyclists come to time themselves for races. Many of them run stop signs, yell at pedestrians, and are generally jerks. I am not a cyclist. For me, cyclists are an out-group. At a certain point, I found myself thinking that cyclists are all jerks. But, once I thought about it, I had to admit that every day I see one or two cyclists behave like jerks, and I see twenty or more cyclists who don’t. Every day, I see a much higher percentage of drivers behave like jerks, but I never came to the conclusion that drivers are jerks. That’s because I’m a driver. They’re in-group. That’s how in-group/out-group thinking works—your mental math is different about in- and out-group members, so you always think that your judgment of the out-group is grounded in empirical data—those two jerk cyclists—but it isn’t, because that data wouldn’t cause you to condemn your in-group (drivers). That’s in-group favoritism.

You take bad behavior on the part of an out-group member as proof that they are basically bad people.

Racism takes in-group favoritism and “naturalizes” it by associating that bad behavior with culture, “race,” ethnicity, or some inherent and inescapable character of a group. My irrational assessment of cyclists wasn’t racism not just because I never said or thought the word race, but because “cyclist” isn’t a category associated with an ethnicity, race, country of origin. Once that cyclist wasn’t on a bike, I wouldn’t assess them as out-group. Racism has two parts: it is in-group/out-group thinking that makes out-group an inescapable identity; also, it is the world in which privileges are (generally unconsciously) given to the inescapable identity of in-group.

Here I’ll review some of the more recurrent categories that scholars use for talking about kinds of racism:

• Cultural racism. It’s important to keep in mind that the word “race” was used interchangeably with “people” until the early twentieth century (and many people used it that way even longer). Thus, people might talk about “the French race” or “the Irish race” or try to pretend that Jews are a “race.” They were naturalizing the borders and social groups present at that moment in time, by pretending that there were necessary consequences of being a member of a particular language group, within certain borders, or some other odd quality. It was common for people to talk about “race” when they meant religion (as in the case of talking about the Irish race, which meant Catholic). Cultural racism never came up with a coherent definition of “race,” nor used it consistently. Many scholars believe cultural racism is a new phenomenon, with the discrediting of biological racism (the only good thing the Nazis did), but really it’s just a return.

• Biological racism. In the eighteenth century (or perhaps earlier) there was a need to defend a new kind of slavery. Slavery is a long tradition, but, with the exception of the Spartans’ enslavement of the Helots, it wasn’t perpetual—meaning that you might be enslaved because you lost a battle or got indebted, but you could get out of it, and your children weren’t necessarily slaves. The consensus among scholars is that, as the economic practice of “perpetual slavery” (you could be born into slavery, there might be no way out) came to dominate in some areas, there was a need to naturalize it—that is, make it not just an economic or cultural practice, but something grounded in nature. This was particularly important, since the New Testament lists slavers among people who are sinning, and the Hebrew Bible has passages about how to handle slaves violated by the practices dominant in many “Christian” communities.

Thus, through the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, experts were trying to find ways to argue that some races (a term they never managed to define) deserved to be enslaved. This is an example of the just world model, or the just world hypothesis (that is, the tendency to assume that the world as it is is just, and so everyone is getting what they deserve—if you’re a slave, you did something or are someone who deserves slavery). This was the era of categorizing (and putting into hierarchies) all the flora and fauna, and so it was an era of saying that differences among human groups were biologically determined.

And there was a tendency to make all taxonomies (ways of categorizing) hierarchical. This was an old notion—that the entire world of God’s creation could be put into a Great Chain of Being. Thus, just as we could say that an ant is lower than a human, we could say that an Italian is lower than a Greek (note, still, there is no coherent definition of race). This all predated Darwin. And, in fact, Darwin didn’t endorse the notion that an ant was “lower” than a human, and he was anti-slavery. Darwin didn’t endorse the notion that evolution heads toward perfection, that some beings are better than others because they are more evolved (the teleological explanation of evolution). But many people used his notion of competition among species to justify how some groups (which they called “races”) had come to dominate others. So, again, the just world model.

• Institutional racism (sometimes used interchangeably with systemic racism)

I think the best way to explain this is for you to think about Parlin (the building). When the building was built in 1953, it didn’t have ramps, only stairs, so it was (and still is, I think) pretty much inaccessible for anyone with even mild problems with stairs. The people who designed the building didn’t get up in the morning and think, “Oh, boy, how can we design the building so it discriminates against disabled people?!” They just didn’t think about disabled people at all. (Which is kind of weird, since lots of students, faculty, or staff end up on crutches at some point.) Institutional racism often comes about people just don’t think about someone having experiences different from theirs—teachers who only include authors of their ethnicity in coursework, or putting a lot of emphasis on standardized test scores in fields or programs where those scores have little predictive value. But it also comes from the ways that unconscious racism can influence decisions, such as a tendency for teachers to come down harder on AAVE than other dialects (because they don’t even realize that they think AAVE is somehow “worse” than other dialects), or operating on the default assumption that all Latinx students are ELL. This really interesting study of how lawyers assess resumes shows that they found more typos (and generally assessed resumes more harshly) if they believed the applicant to be African American. Lawyers use preemptory challenges in ways that hurt non-white defendants disproportionately, and jury deliberations are notoriously influenced by unconscious racism (and sexism, and various other biases) in many ways, ranging from mistrusting testimony by POC to giving POC defendants harsher sentences.

Why is it so hard for us to have good disagreements about race?

We have trouble arguing productively about race as a nation because we have trouble disagreeing about anything. A lot of people believe that the truth is obvious to people of intelligence and goodwill, and that, if two people disagree, one of them is wrong—the people who disagree with us know they’re wrong, and are arguing for perverse reasons; they are idiots corrupted by their political agenda; they are greedy and just looking out for themselves. We are not good at acknowledging that disagreement might be legitimate, or that we might be wrong.

The dominant model for how we know things (an epistemology) is “naïve realism,” which says that you just have to look at the world in an unprejudiced way, and you can see the truth. In fact, we reason by confirmation bias, so that, if you believe that Lithuanians are rude and interrupt everyone, then if someone is rude and interrupts everyone, you’ll be likely to decide that person is Lithuanian, with little or no evidence to that effect. Oddly enough that experience will enable you to think that your racism about Lithuanians is rationally grounded. It isn’t. You don’t know if they are Lithuanian.

If you believe that Lithuanians are rude and interrupt everyone, and you know that someone is Lithuanian, then you’ll notice every time they interrupt anyone and interpret behavior as rude that you wouldn’t consider rude if you did it. (The cyclist example from above.)

Naïve realism gets entangled in supporting racism in three ways: first, naive realists believe that they can know if they’re racist by asking themselves if they are consciously operating from racism; second, they believe that they can know whether someone else is racist by asking themselves whether that person seems racist; third, it enables racism by making people think that races are real—they can look and see different races, and they can see that That Race is bad (again, the cyclist example).

More important, naïve realism—the notion that you can know if something is true by asking yourself whether you really think it’s true—means that people, when presented with disconfirming evidence, just recommit to their beliefs. Naïve realism is confirmation bias; it’s in-group favoritism.

So, one reason people engage in racist actions is that they think they would know if they were doing something racist (a combination of the notion that racism is always conscious and naïve realism), but another is that our entire complicated, nuanced, rich world of policy options is reduced by political parties, the media, and our choices regarding media consumption to the false binary of liberal v. conservative. If you’re in an informational enclave, and you or an in-group political figure is criticized for doing something racist, you’re unlikely to hear the evidence that might support that claim (but you’ll hear about all the evidence for out-group political groups or figures).

We all inhabit worlds of information, and some of those worlds are explicitly in-group (Fox, MSNBC, Infowars, Rush Limbaugh, Mother Jones, Reason). And what those rabidly factional groups do is spend most of their time persuading you that the opposition arguments are terrible, so you shouldn’t even listen to them. This is called inoculation. It isn’t new. Media, pundits, and political figures making racist arguments have always generated support among their base by arguing that, “We are good because those people are awful” and then reducing all the various complicated ways that people disagreed into “Them” (a dumbass parody that no one actually advocated). In the US, in the antebellum era, you either supported the most extreme proslavery positions or you wanted slaves and white women to have sex, you wanted race riots; in the era of segregation, you either supported the most extreme segregationist policies or else you supported black men and white women having sex (I’m not kidding—this was a big deal), a “coffee-colored” world, and the decline of our civilization.

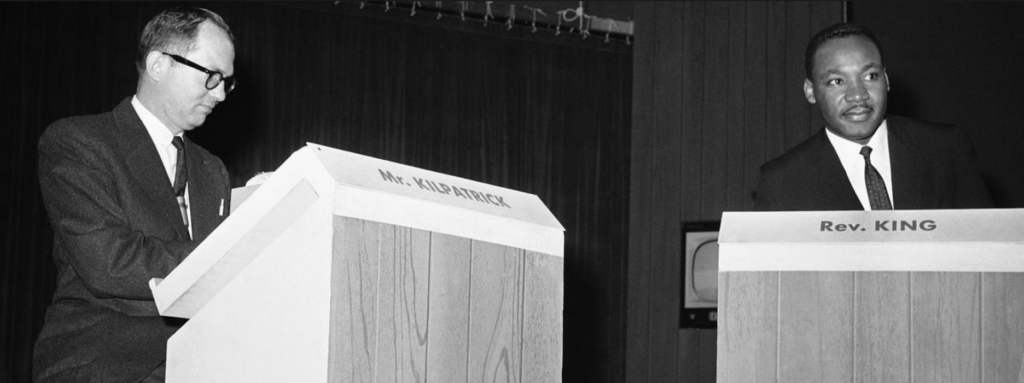

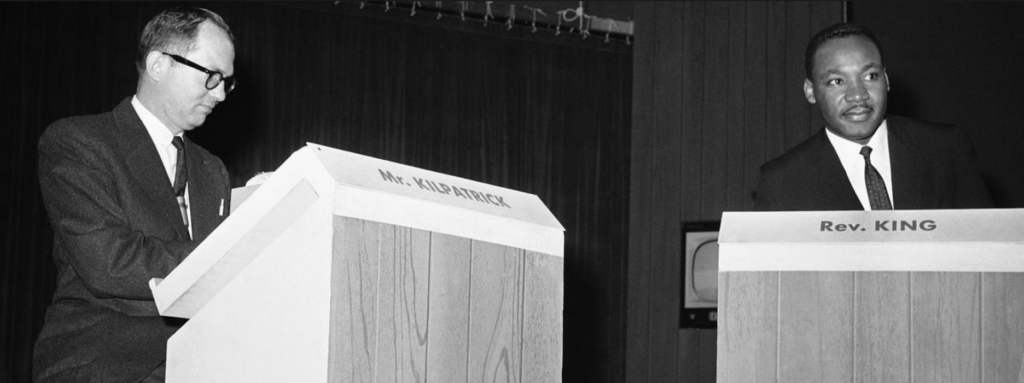

Those arguments (and ideologies) were illogical and entirely false, but they appeared to have a lot of data. Most important, they seemed reasonable to people who thought that the desire to end slavery and segregation was motivated by the desire for black men to have sex with white women. It wasn’t, but the pro-slavery and pro-segregation media presented that as the only real argument that critics of slavery and segregation had. When you watch or read the King/Kilpatrick “debate,” notice that Kilpatrick never really responds to what King actually says, but is obsessed with sex; you’ll see Theodore Bilbo do the same with black scholars—Kilpatrick and Bilbo have been inoculated against counter-arguments, so they don’t even listen.

As I’m emphasizing throughout this class, we should talk about racist actions, but our culture tends to talk about whether a person is racist. That’s another reason our arguments about racism are so bad. Many people believe that racist actions are the consequence of deliberate decisions to be racist on the part of people who consciously decide to engage in an action that they themselves believe to be racist because they are racists. In this (false) world, there are some people who are racist, and everything they do is deliberately racist.

Also, too many people think there is a binary between racist (really bad) or not racist (good). Some people describe it as a continuum, and that’s a better model, but I think that’s just part of it, because you can have (as you’ll see in the readings) something that argues against biological racism but rests on the premises of cultural racism, or that uses somewhat racist arguments to end a very racist policy.

Our culture also tends to assume that there is a binary of shame v. pride in how we think of ourselves, our nation, our culture—there is the assumption that you are either proud of yourself (meaning you have only done good things), or you think you’ve done something bad (in which case you’re ashamed of yourself). This applies to your sense of your group—you can either take pride in your group (meaning you believe it’s perfect), or you can think your group has behaved badly (in which case you should be ashamed of your group). That’s an actively dumb way to think about ourselves, our culture, our in-groups.

Imagine that someone says to you, “Hey, I think what you just did there was kinda racist,” or “America has a racist past,” or “The Confederacy was racist.” If you believe the three false assumptions above—racism is necessarily an identity argument, something is racist or not, and you can either be proud or ashamed–, then here’s what you hear: “Hey, you are a bad person who should wallow in shame because you decide to be racist every day and every way.” Or, “As an American, you should wallow in shame about the US and spend your whole life apologizing because America and Americans are entirely evil for their deliberate racism.” Or, “If you live in a CSA state or are descended from anyone who fought for the CSA, you should do nothing but wallow in shame and hate your ancestors because they were completely evil.”

You can think your ancestors were completely evil and yet not feel that you have to wallow in shame, you can think they were evil for their racism, but good for some other reason, you can be proud of the good things they did and remorseful for what they did wrong. You can try not to take personally criticisms of your in-groups and acknowledge flaws. There isn’t a binary of shame v. pride—to take pride in something, it doesn’t have to be perfect. And shame is not a particularly useful response to criticism (in fact, it shifts the stasis from what you did to who you are—which is sidetracking).

Think about it this way. You’re driving along, and someone (call him Chester) changes lanes into you and causes y’all to crash. Your car is really damaged. And Chester gets out of his car and you have this conversation:

You: You just changed lanes into me.

Chester: No, I couldn’t have done that because that would make me a bad driver and how dare you call me a bad driver! I am a good person. I foster blind owls, and teach a literacy class at the local public library, and pick up trash on the road.

You: Um, that’s all great, but you did change lanes into me.

Chester: I couldn’t have done that because I’m a good driver. I have never been given a ticket (because I treat police officers with respect, unlike some people), I think terrible things about very unsafe drivers, and I always check my blindspots. And I think the real issue here is that you’ve accused me of being a bad driver.

You wouldn’t say, “Oh, wow, well, yeah, that’s all evidence that you are a good driver, so you can’t possibly have just changed lanes into me.” That would be an absurd conclusion. You would say, “I don’t really care if you’re normally a good driver. I don’t care who you are–I care about what you just did.”

Yet, when someone does something racist, and someone else points it out, we have the “I can’t have changed lanes into you because I’m a good driver” argument. We need to stop having that argument.

There isn’t some binary of being racist (bad, shameful) and not racist (good, pride). Racism isn’t about who we are; it’s, to some extent, about what we do, but even more, it’s about how unconscious biases on the part of many people have a particular outcome. The solution to racism isn’t that some group should feel shame, or stop feeling pride; the solutions are complicated, but we won’t get to those solutions unless we argue better about race.

Hence this class.