[I’m normally a big advocate of linking for claims. In this post, I won’t, for various obvious reasons—I’m talking about what people on really awful websites are saying, and I’m uncomfortable giving them the traffic. My decision not to include links means that I’m not presenting this as a set of defensible claims in an argument about policy, but a personal reflection based on my wandering around dark corners of the internet. My hope is that it will make people curious so that they will google the various claims I make. If you google, and think I’m wrong, feel free to comment.]

A lot of people are shocked by the current rise in antisemitism, but I’m not, nor is anyone who knows anything about how racism works. It’s confusing to a lot of people because far too much public discourse about politics relies on the false binary of left v. right (a false binary not made any better by pretending it’s a continuum) and actively damaging stereotypes about what racism is.

For people whose (racist) stereotype of Jews is that they’re lefties, it seems puzzling that other “lefties” would be antisemitic. For people who think that racism is undying and relentless hostility, and whose (racist) notion is that Jews are all supporters of the most extreme policies of Israel, then it’s puzzling that anyone on the right would be antisemitic, let alone any supporters of Trump would be, since his daughter and son-in-law are Jewish.

That there is violent antisemitism on the part of people our gerfucked political discourse identifies as left and right gets rabid factionalists biting their own tails and engaging in a lot of no true scotsman, but it really should be seen as the kind of anomaly that gets people to reconsider the taxonomy.

Our culture is demagogic because it makes every issue a question of identity instead of policy, a rhetorical choice openly advocated by the GOP “Southern Strategy” in 1968, but as old as antebellum politics about slavery. As long as we try to understand our political world in terms of left v. right, we will never understand the pernicious strain of antisemitism in American politics. Antisemitic terrorist incidents will be things we fling at one another as proof that Dems or GOP are evil, rather than facing, honestly, that antisemitism is a thread deeply interwoven into American politics, all over the political tapestry.

Antisemitism is often identified as the first racism, and the origin of racism is often placed in the moment that Spain decided to purify itself of Jews and Muslims (which would mean that antisemitism and Islamaphobia are fraternal twins). Selecting that moment in time might seem weird to anyone who is familiar with earlier writings. Julius Caesar was pretty dismissive about various other groups he fought, and John Chrysostom (an early father of the church) flung himself around about Jews. Cicero has a speech in which he argues that certain witnesses should be ignored because, you know, they’re Jews, and you can never believe them. At least one scholar has argued that racism in the Western world started with the Greeks.

The argument for putting the germ of racism in Spain in the era of the converso policies is that this was a moment when assimilation wasn’t enough. This was the moment was policies were grounded in the sense that some people are essentially different and can never really assimilate.

I think that’s a good way to think about racism: it isn’t about personal hostility, nor about stereotyping other groups (even if negatively) but about a sense that those people are essentially different, and can never really assimilate (I think there are weird exceptions made for token whatevers, which I’d like to call poliocentrism, but that’s a different post).

Every group, from your book club to your nation-state, will fuck up. And when it fucks up, you have a lot of choices. You might decide that it fucked up because everyone was engaged in bad ways of making decision. Or, you might decide it wasn’t about how we decided but these decisions, that somehow triggered us too much to decide well. Or, you might decide that it was about that bitch eating crackers who somehow forced a decision on us or seduced those assholes… or something. You’ll scapegoat the bitch for everything.

Sensible people genuinely engaged in processes of good decision-making take the first choice. The rest of us take the third. And, for most of the history of Western Europe, the bitch eating crackers was Jews.

My family (for reasons I still can’t fathom) once took a road trip that involved our driving along I-5 in California right after it was paved. There were signs saying “NEXT GAS 225 MILES.” We were driving a station wagon with luggage strapped (badly) to the roof. At some point, we realized we’d lost a suitcase far too long after it was reasonable to go look for it. For years after, if any of us lost anything, we would tell our mother that it was in that suitcase. We would tell our mother that things had been in that suitcase we didn’t even own when the suitcase was lost. If what we had been claiming was true, that suitcase would at least have been the size of an intercontinental container. Perhaps two.

Jews are the lost suitcase of Europe.

Some have argued that, since Jews and Muslims were essentialized at the same moment, they’re just as much victims of racism as Jews. But, Muslims were never scapegoated for the ills of Europe. They were other, but not Other (although now they are Other).

Once you understand that Jews are the lost suitcase of Europe—that is, a group that can be scapegoated cheerfully free of any rational argument that might involve coherent arguments with actual evidence—then you can understand the role of “Jews” in demagoguery. It’s never about actual people who are actually Jewish who are actually engaged in actual acts. It’s about a kind of Platonic ideal of “Jews” that can be used as a weapon in the factionalized argument you’re having.

There are three narratives about Jews that have been used to argue for their marginalization, expulsion, or extermination, and we’re seeing all of them right now.

First, they aren’t really “us.” Jews are more clannish, less tied to the country than they are to Zion, better at money. Sometimes, this difference is presented as admirable (as in a recent speech of Trump’s); more often, it’s presented as a reason they should be prevented from joining our country, let alone our country club, or actually expelled as dangerous—an argument that was persuasive in such disparate situations as Madison Grant’s successful arguments that there should be severe limits on Jewish immigration in 1924 and Josef Stalin’s successful pursuit of the Doctor’s Trials.

Second, they are Christ-killers, who need to be kept present so that we can convert them at the last minute and thereby enact our (exegetically indefensible) reading of Revelation. This was, until very recently, the official position of the Catholic church, and a lot of pro-Israel anti-Semites share it. What a lot of people don’t know is that much of the current “evangelical” support of Israel—the kind dominant in the Trump Administration–is a consequence of their reading Revelation in an incoherent and intermittently literal way. Granted, these are the same people who read the story of Sodom as a condemnation of homosexuality, so their exegetical skills are not exactly reasonable, and they’re pretty much a case study in confirmation bias and Scriptural cherry-picking, but what matters about them is that they want nuclear war in the middle east.

Many self-described Christians believe that Jesus will come when “the Jews” are converted to Christianity. That’s a belief that has been repeatedly disproven, but we’ll set that aside. (The people who saw themselves as founding a New Jerusalem thought it meant them. It didn’t.) The important point is that there are a lot of people who support confrontational politics in regard to the middle east because they want a nuclear war that would reduce the number of Jews who need to be converted (I think Pence is among them).

So, anti-semitism is deep among a certain kind of evangelical, even if it’s coupled with support for Israel and a weird kinda sorta if you squint support for Jews (whom they hope will either die or convert).

Third, we aren’t expelling or exterminating Jews because of their race, but because Jews all have bad politics (or you can’t trust any single Jew not to have the bad politics of some of them—the poisoned peanut analogy). It’s important to remember that much of the genocide in Central Europe was under the cover of killing “partisans.” People making this kind of argument says it’s about politics (or culture) but that political determination is always based in race, and they’d really appreciate if you didn’t mention that.

And antisemitism sometimes masks itself as praise. I am old enough to remember people saying, “I’m not racist; I admire that colored people are great with children, and have such a wonderful sense of rhythm.” They thought it was praise as it wasn’t saying that all African Americans were bad, but it was racist af because it was praising a group for talents that aren’t valued. And granting African Americans some (only sorta) “good” qualities, was what they seemed to think was a “get out of racism free card” for what they were about to say next. (Much like, “I’m not racist, but….”) In the case of “the Jews” (as though they are all the same), the “praise” is precisely what Trump said: Jews are good with money and ruthless in their pursuit of it.

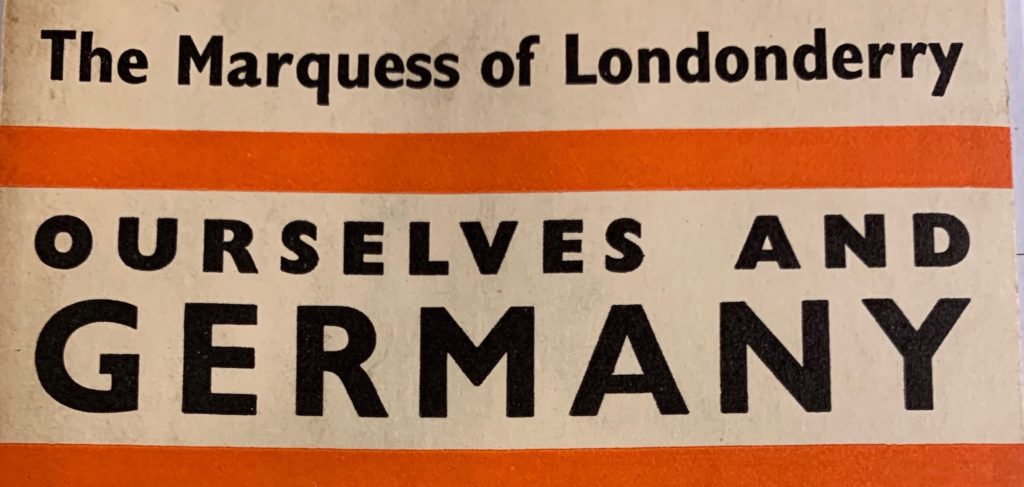

That “praise” is the fuel for the narrative that equates modernization, globalization, “international banking” and Jews. That false equation is as old a connection as the volkisch myths on which the Nazis drew. The argument is that Jews don’t have a nation, they have a global relationship. The Nazis and neo-Nazis love(d) that narrative, although it’s cheerfully fact free (after all, the same could be said of Christians, Muslims, or any other religious group that claims to value their religion over other ties).

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that Nazis, neo-Nazis, and white supremacists would promote old and busted narratives about Jews being involved in global conspiracies to control all the money, but exactly the same narratives are promoted by far too many people who self-identify as lefty.

I crawl around dark corners of the internet, and, for complicated reasons, at one point I found myself crawling around the weirder parts of the anti-globalist rhetorical world, and I found that antisemitism is alive and well there. I found Holocaust deniers (Holohoax, they call it), people citing the Protocols as though that were a reasonable source, promoting exactly the same myths as neo-Nazis (Jews control the media, own more of the world’s wealth than actually exists, and so on). Every once in a while, I’d run across the old and busted claim that none of the Jews who worked in the WTC showed up that day for work (they did).

My point is that antisemitism is all over the political tapestry. It isn’t an issue of left v. right. It’s an issue of antisemitic tropes being ones that people all over the political tapestry find useful because it’s woven in there, and, yet, oddly enough, the accusation that they are antisemitic is also all over the political spectrum.

We need to stop saying that having a Jewish friend or relative means a person can’t be antisemitic—Adolf Eichmann made the first argument, and Magda Goebbels made the second (and it was true in both cases). We need to stop saying that supporting Israel means you aren’t antisemitic—supporting Israel because you want most Jews to die is antisemitism. We need to stop pretending that simply because you have a lefty agenda you couldn’t possibly be endorsing racism.

We need to understand how deep antisemitism runs in our culture, and we need to stop pretending it’s only a problem for them. It’s true; they are antisemitic. But so are we.