My first experience of the digitally connected public sphere was Usenet in the mid-80s, and since then I’ve spent a fair amount of time arguing with people, including arguing with extremists. Here are some notes I recently made about what I’ve learned by arguing on the underbelly of the internet.

Highly-educated people don’t necessarily argue better than people with a lot fewer degrees.

People reason associatively, grounded in the binary of some things are good, and some things are bad. If something is associated with a good thing, it can’t be bad in any way. (This explains why people, in response to substantive criticism of a public figure, say, “S/he couldn’t have done that because s/he did this completely unrelated good/bad thing.”

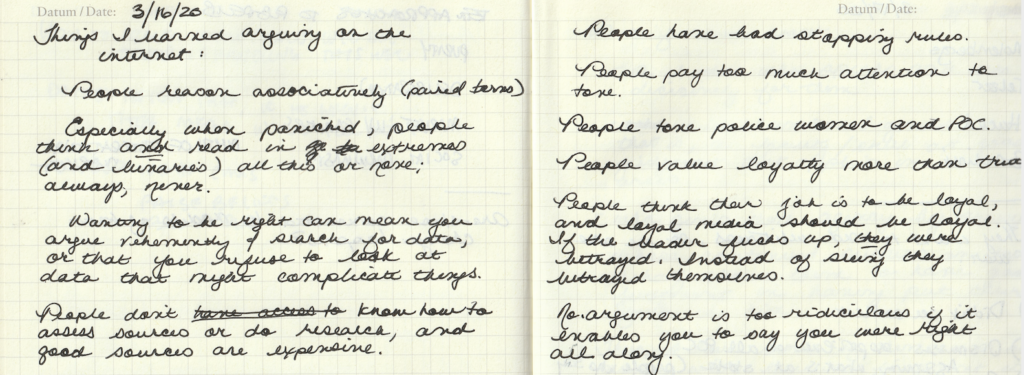

Some (many?) people think and reason in binaries and extremes (all or none, always or never) when they’re threatened (and some people are easily threatened). Not everyone does this, but the people who don’t are rare; I’ve seen it all over levels of education, ideological commitment, apparently calm demeanor, discipline. It’s about how people handle threats (hell, I’ve had people who self-identify as skeptics do this, and I’ve caught myself doing it).

Some people argue vehemently because they really want to be right, and that means that they want really good arguments on the other side, and they’re open to good opposition arguments; some people argue vehemently because they are swatting away any disconfirming information. Those two kinds of people can look really similar in terms of tone, vehemence, and even snarkiness. It takes time to figure out whether someone is open to argument.

On the other hand, people who claim to dislike argument and just want everyone to get along can be the most rigid thinkers and least open to new ideas.

Far too many people don’t know how to do research or assess sources, and much teaching on that subject makes this situation worse. Also, having access to good sources is expensive, and doing good research is time-consuming.

Instead of doing research on the basis of the quality of argument of sources, people tend to rely on gut instincts about trustworthiness, and that generally means confirmation bias and in-group favoritism. This, too, is all over the political and educational map.

People completely misunderstand the issue of “bias” and have an incoherent epistemology about perception—highly educated people might just be worse on this than people on the street. They’re certainly no better.

People use bad examples to stereotype out-group and good examples to stereotype in-group.

People confuse “giving an example” (a datum or quote) with proving a point.

People engage in motivism way too fucking much.

Extremists argue the same way, regardless of where they are on the political spectrum, or even if it’s a political question at all.

People have bad stopping rules when it comes to research.

People pay too much attention to tone.

People tone police women and POC way too fucking much.

Charismatic leadership is a drug, and a lot of people are way too high on it.

People value loyalty to the in-group (and especially to the leader) more than truth because they redefine truth as loyalty.

No argument is too ridiculous if it enables you to say that you were right all along.

If a media source is in-group, makes their audience feel connected with them, makes their audience feel good about their beliefs and choices, then that audience will remain loyal no matter how many times that media source is just completely wrong.

Far too many people reason deductively from non-falsifiable premises, and think they’ve thereby proven a point to be true.

People are desperate to resolve cognitive dissonance, especially the dissonance created by being fanatically committed to a faction (or unwilling to consider any disconfirming information) and wanting to see ourselves as fair, compassionate, and rational.

People reason from identity way too fucking much.