Hey all, I was on a fun podcast with Johanna Hartelius and Jason Micheli, talking about demagoguery and the most recent book.

Retired Professor, Writing Center Director, Scholar of train wrecks in public deliberation

Hey all, I was on a fun podcast with Johanna Hartelius and Jason Micheli, talking about demagoguery and the most recent book.

When we have taken time and trouble to learn something, we tend to value it—simply because it was a PITA to learn. So, when something gets taken out of the K-12 curriculum, people of a certain generation can have a gleeful “kids these days” moment. When I was young, memorizing the state capitols was dropped from the curriculum in a lot of places, and I remember hearing people bemoan the debacle that had come to be known as education. As it happens, when I’m bored, I will sometimes try to write the states in alphabetical order. If I’m really bored, I’ll then try to identify each state’s capitol. I usually fail. My life would be no worse had I not been taught to memorize the capitols.

[ETA, since, apparently, I was unclear on this point: I don’t remember the state capitols because, between fourth grade and until I was an adult in boring meetings, it was never a skill I needed. Something that you’re forced to learn that you then never or rarely learn is something you forget. That some people in some very specific fields might find that knowledge useful doesn’t mean that it should be a required part of K-12 curriculum.]

As it happens, I write in cursive a lot. It is useful for taking notes quickly, although nowhere near as useful as shorthand—which I was never taught. If we’re concerned about people being able to write quickly, then we should teach shorthand.

When I was teaching, I had some students who wrote exams in cursive, but very few It’s faster to write an exam in cursive, but not necessarily a good choice. Even I think cursive is harder to read, and rhetorically it’s a poor choice to irritate a grader by writing in a way that takes extra time to decipher.

A lot of students wrote in what amounts to italics, and that made a lot of sense (sloped and somewhat looped, but without special characters for letters like capital Q). It’s as fast as cursive, but doesn’t take any particular training to write or read.

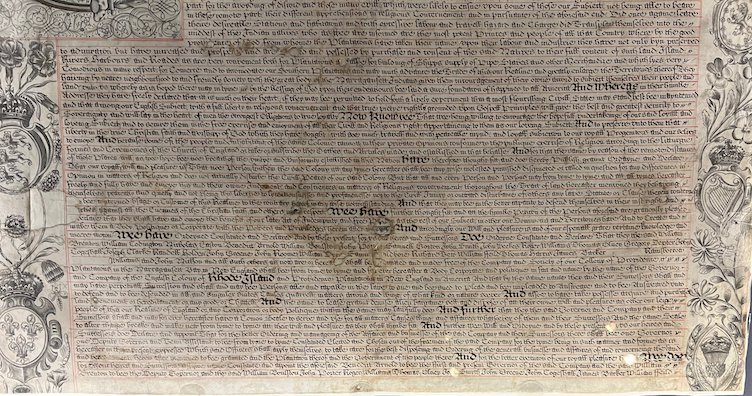

The other argument I hear for taking class time to teach cursive is that people won’t be able to read historical documents. This argument puzzles me. Printed documents tended to be in block letters from the beginning of the 19th century. Books were in block letters long before that. Some documents are in cursive (especially proclamations), but not always the same cursive.

I read a fair number of historical documents, and I do get a thrill when I’m looking at an original version of something like the Magna Carta or Declaration of Independence. But it’s that it’s the thing, not that it’s in cursive. I’m not sure that a person understands the document any better if they read it in cursive rather than block letters.

And, in fact, what makes reading those documents difficult isn’t the cursive, but first and foremost the content. The historical context, references, genre. The language is often archaic, and usually invokes legal or philosophical concepts that are unfamiliar. To the extent that deciphering them is hard, it isn’t because they’re in cursive, but usually that the font is serif, and the kerning is confusing. And they aren’t always in cursive. For instance, knowing cursive doesn’t help someone read the Rhode Island charter.

So, really, people need to stop worrying about not teaching cursive. What we should really be getting upset about is that students aren’t being taught geology, sex ed, history, argumentation. I don’t care if it’s in cursive or not.

The e-book version of Deliberating War is available from Springer!

“Drawing on a rich collection of examples from ancient Greece to the present day, Patricia Roberts-Miller ably demonstrates the failure of political leaders to engage in deliberation when choosing to undertake, continue, or escalate war. Instead, they reframe the situation, deflect the real issues, demonize the enemy, and make themselves the victim, all to convince themselves that war already has been forced upon them and they have no choice. Sometimes wars are justified, but political leaders, specialists, and citizens will all benefit from this accessible work that shows what can happen when deliberation is an essential feature of the rhetoric of war.” (David Zarefsky, Northwestern University, Author of “Lyndon Johnson, Vietnam, and the Presidency: The Speech of March 31, 1968”)

“Deliberating War is a thorough, insightful, and well-written discussion of how people in the Western tradition deliberate about war and treat deliberation as war. In discussing various kinds of war, and various kinds of deliberating about war, Roberts-Miller illuminates how and why some of these are more dangerous than others. This book is a must-read for scholars in history, political science, and communication who care about war, democracy, and the relationships between them.” (Mary E. Stuckey, Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences at Penn State University)

“Deliberating War takes rhetoric’s relationship to war out of the realm of meaningless metaphor and into the realm of real, critical, potentially cataclysmic importance. For millennia, debates about war have translated to the battlefield and events on the battlefield have translated into debates about who we are, what we value, and how we should act towards one another. Given how high the stakes are, Roberts-Miller demands that readers grapple with how politicians use rhetoric to drag people to war. But politicians don’t act alone, so she also demands that everyone learn to choose their words more wisely in matters of war, politics, and life.” (Ryan Skinnell, Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Writing, San José State University)

“Patricia Roberts-Miller’s Deliberating War is a probing study of the rhetorical dynamics that feed on political factionalism to displace deliberation and transform the trope of “politics as war” into real war. It is a sustained and close study of multiple cases of armed conflict that cross historical periods and involve an assortment of adversaries. Various rhetorical practices are insightfully analyzed for how they obstruct democratic deliberation, including how the call to arms is strategically framed, which fallacies typically are deployed, which issues are obscured and left unaddressed, and how the dynamics of the discourse can even carry adversaries into a war they wanted to avoid. Her critique of appeasement rhetoric is particularly acute, as is the point she makes about the militarization of politics in general, which reduces the spectrum of normal policy disagreements to political combat. This is an important work of scholarship on the consequences of literalizing the metaphor of war.” (Robert L. Ivie, Professor Emeritus in English (Rhetoric) & American Studies, Indiana University, Bloomington)

“In this incisive and necessary book, Patricia Roberts-Miller skillfully interrogates the political factors in the decisions made by nations to go to war and the critical lack of deliberation when making those decisions. Her analysis captures the enormity and the tragedy of governments choosing war without losing the humanity of those who must carry out those decisions. In addition to political rhetoric scholars, this book should be required reading within the halls of the U.S. Congress, inside the walls of the Pentagon, and in the classrooms of military academies and war colleges.” (Derek G. Handley, Assistant Professor of English, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (CDR, U.S. Navy Retired))

We were asked to do an epideictic speech, and one kind of epideictic is psogos: the blaming or condemnatory speech. And I want to condemn the biased/objective binary on the grounds it is necessarily and inherently authoritarian, and thereby makes democratic speech impossible.

The term “authoritarian” is vexed, so I’m going to use an old-school definition: an authoritarian system aspires to univocality, uniformity, asymmetric communication, and reified social policies, values, and relations. It assumes that the nation as a whole should be a rigid and ontologically grounded hierarchy of power and privilege, in which the people at the top decide for those below them; and all institutions within that nation are similarly constructed—the police, families, governments.

Authoritarianism presumes that the hierarchy is legitimate if and only if the people in positions of power are ones who either have direct and unmediated access to the truth (i.e., they are not “biased”), or who are following the dicta of those who do. Because of that direct access, good leaders can invent or enact the correct policy agenda in all realms. So, hidden is the presumption that there is no such thing as significant legitimate disagreement, and that, in every disagreement, there is a single “right” answer that good people can perceive.

A hierarchy’s use of violence, coercion, propaganda, exclusion, and extermination is seen as legitimate as long those actions are in service of preserving the purity of the community, rewarding and empowering good people (i.e., in-group), coercion or extermination of bad people (i.e., out-group); and all in service of forcing people to do and believe the narrow range of actions and beliefs that are “right.”

And it’s that phrase—narrow range of actions and beliefs that are right–that makes it clear how this hierarchy is not just one of power; it is epistemological, and the solution to every problem is to give unlimited power to who know what is “right”—that is, those who are not biased.

“Biased” sources and people are presumed to be ones that view the world from a narrow perspective; so, necessarily associated with the biased/objective false binary is the equally false binary of particular/universal.

As many others have pointed out, we don’t undermine authoritarianism by saying that we’re all biased, since that doesn’t end the hierarchy; it just makes it one of open and unconstrained violence. We end up with some version of Social Darwinism. The mistake is the term “biased.” It’s more useful to think in terms of “biases” (that is, cognitive biases) and perspectives, and to try to correct for the former and celebrate the latter.

This paper came out of my being puzzled by a paradox I kept running across in the various deliberative train wrecks I study—the intermittent moralism of Machiavellian approaches to public policy disagreements. “Machiavellianism,” only orthogonally related to what Machiavelli actually said, claims to treat means as morally neutral, often in service of some version of power politics or neo-Social Darwinism. But this amoralizing of means is both rhetorical and flickering—American intervention in Vietnam, for instance, was advocated on the grounds of moral necessity and amoral power politics, sometimes in the same document.

What I’ll pursue in this paper are some of the somewhat paradoxical rhetorical consequences of this disingenuous framing of means as amoral.

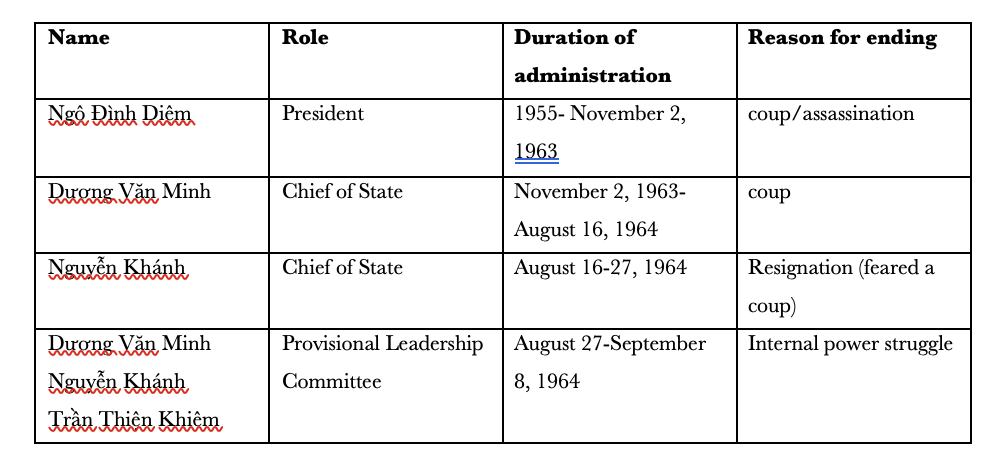

I’ll focus on US decision-making regarding Vietnam in August of 1964. August of 1964 is one of several moments of escalation, with attention generally on LBJ’s decision to lie in order to get the Tonkin Gulf Resolution passed on August 7. But I’m more interested in the chaotic debacle that was General Nguyễn Khánh’s not-quite month as Chief of State. I’ll start by discussing the objectives (ends) at the time, the necessary conditions for success, the actual conditions (as described by US decision-makers), the means they chose, and finish with how Machiavellianism played into it.

Ends In an August 10 “situation report,” Maxwell Taylor, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and recently appointed US Ambassador to the Republic of Vietnam said that the “Communist strategy” was not

“To attempt to defeat the superior Republic of Vietnam military forces in the field or to seize and conquer territory by military means. Instead, it is their announced intention to harass, erode and terrorize the population into a state of such demoralization that a political settlement favorable to the Communists will ensue.” (#306, 657).

Robert McNamara would later identify policies in 1964 as oriented toward “the objective of destroying Hanoi’s will to fight and its ability to continue to supply the Vietcong” (In Retrospect 152). In an important –strategy setting—document in August of 1964, McGeorge Bundy said we must “make it clear both to the Communists and to South Vietnam that military pressure will continue until we have achieved our objectives [….] leaving no doubts in South Vietnam of our resolve” (#313, 675). By persuading “the Communists” that the US would not give up Vietnam, it was hoped that “the Communists” could be persuaded that a divided Vietnam—much like Korea—was the best deal they could get, and therefore take it.

Necessary Conditions To achieve those ends—a Hanoi willing to agree to a divided Vietnam—certain conditions had to exist. RVN had to be an effective and largely victorious force, capable of exterminating the insurgency without alienating the populace. The “pacification” program was crucial for achieving several of the conditions—denying communist support for the Viet Cong, maintaining the morale of the populace, achieving military victories—and it depended on “clearing” certain areas of Viet Cong agents and supporters. South Vietnam had to have a competent, trusted, and stable government. The South Vietnamese people needed to support that government, and support the war (which could only happen were the first condition met). The US had to signal willingness to throw limitless resources at the conflict. These various conditions tended to be characterized as issues of “morale” (or its opposite—“defeatism”) in official documents, documents that admitted none of those conditions were present.

Actual Conditions In that August 10 “situation report,” Taylor acknowledged that the South Vietnamese military was weak, while trying to put a positive spin on it: “In the view of US advisors, more than 90 percent of the battalions of the army are at least marginally effective.” (#306; 661). The pacification program was “proving to be a most difficult one primarily because of the inefficiency of the ministries, their ineptitude in planning and their general lack of spirit of team play” (Taylor 659). In a memo ten days later, Taylor said, “that the present in-country pacification plan is not enough in itself to maintain national morale or to offer reasonable hope of eventual success.” But the worst was the government. The US had endorsed the November 1963 coup on the grounds that Diem was corrupt, incompetent, and tremendously unpopular. He had collaborated with the Japanese (unlike Ho Chi Minh, who fought them), was brutally persecuting Buddhists, and may have been considering a peace treaty with Ho. The hope was that replacing Diem would increase Vietnamese commitment to the war by putting in place a more popular, competent, and bellicose government. It didn’t work (as can be seen in the chart at the top.

Taylor said

The most important and most intractable internal problem of South Vietnam in meeting the Viet Cong threat is the political structure at the national level. The best thing that can be said about the present Khanh government is that it has lasted six months and has about a 50-50 chance of lasting out the year [….] It is an ineffective government beset by inexperienced ministers who are also jealous and suspicious of each other [….] However, there is no one in sight who could do better than Khanh in the face of the many difficulties which would face any head of government [….] The attitude of the people toward the Khanh government, mostly confused and apathetic since its inception, is only slightly more favorable than a few months ago. Despite considerable efforts, Khanh has not succeeded in building any substantial body of popular support. (657-658).

August 13, 1964, McGeorge Bundy presented a plan called “Next Steps in Southeast Asia, “a highly important document” (Logevall 217). McNamara would later say that “the memo and its derivatives became the focus of our attention and acrimonious debate for the next five months” (In Retrospect 151). The first sentence of the section, “Essential Elements in the Situation” is “South Vietnam is not going well” (#313, 674).

Taylor responded to Bundy’s “Next Courses of Action” (which he endorsed that one assumption behind Bundy’s proposal (which he believed to be correct) is:

The first and most important objective is to gain time for the Khanh Government to develop a certain stability and to give some firm evidence of viability [….] A second objective in this period is the maintenance of morale in South Viet Nam, particularly within the Khanh Government [….] he must stabilize his government and make some progress in cleaning up his own operational backyard. (690)

The Course of Action that Bundy’s memo advocates, and Taylor endorses, “relies heavily upon the durability of the Khanh Government. It assumes that there is little danger of its collapse without notice or of its replacement by a weaker or more unreliable successor” (692). Ten days later, worried about a coup, Khanh himself would resign and skedaddle to Dalat. He had to be coerced to come back and form a triumvirate. There were no illusions about the instability and unpopularity of the government, and yet the US was pursuing a plan that, as was repeatedly insisted, depended upon a stable and popular government, which US officials knew they didn’t have. They did, however, have one that wouldn’t negotiate with Hanoi.

The Means

One of the “means” necessary for success was preventing peace talks: “We must continue to oppose any Vietnam conference” (#313). After listing the various means the US should take, Bundy says,

These actions are not in themselves a truly coherent program of strong enough pressure either to bring Hanoi around or to sustain a pressure posture into some kind of discussion. Hence, we should continue absolutely opposed to any conference. (#313; 678).

That this was the means was not publicly admitted. But the conservative and “realist” political scientist Hans Morgenthau had figured that out, snarkily noting in an article in New Leader in June of 1964:

Our main immediate problem is apparently not to win the war against the Viet Cong but to prevent the ascendancy of an anti-war government in Saigon. What we are saying and doing must, then, have as its main purpose to prevent the collapse of the morale of General Nguyen Khanh’s government and of its military forces (44).

Thus, American Vietnam policy in 1964 was to prevent negotiations with Hanoi until the morale, bellicosity, and military effectiveness of the South Vietnamese was such that Hanoi (and China) would believe that a divided nation was the best they could possibly get: “We need to apply “a combination of military pressure and some form of communication under which Hanoi (and Peiping) eventually accept the idea of getting out” (#313). The “Next Course” also advocated dropping leaflets, increased training of RVN forces, mining of the Haiphong harbor, “tit-for-tat” actions, only acknowledging successful military actions. Taylor said, “The US Mission has recognized in its information and psychological programs the need to present the Khanh government in its most favorable light at home and abroad, particularly in the United States” (# 306 660).

What I hope is striking to you is that the means were profoundly rhetorical; they were about persuasion—persuading the North Vietnamese they couldn’t win, and the South Vietnamese that they could. South Vietnamese needed to be persuaded to support the war, and both the South Vietnamese and Americans needed to be persuaded to have faith in the Khanh government—its stability, competence, and resolve. But even the American officials themselves weren’t persuaded of any of those things. So, the Machiavellianism came to be the approach to public deliberations—critics of American policy in Vietnam had to be smeared, discredited, and deflected. Preventing reasonable discussion of Vietnam policy itself became a means necessary for the ends.

Machiavellianism

I mentioned earlier that McNamara said the US objective was destroying Hanoi’s will to fight and ability to support the Vietcong. He said, “Neither then nor later did the chiefs fully assess the probability of achieving these objectives, how long it might take, or what it would cost in lives lost, resources expended, and risks incurred” (152).

The amoralizing of means didn’t mean they were actually neutral—there is nothing morally neutral about napalm—it just meant that people could deflect or even demonize public discourse that criticized the ends or means. The ends (and therefore the morality of the means) are themselves outside the realm of argument—they’re simultaneously obscured and circular (since the postulated morality of the ends or intentions justifies being dishonest about what the ends or intentions actually are). We can’t argue reasonably about the ends—because they’re postulated as moral—and we can’t argue at all about the morality of the means. Thus, amoralizing policies (the means) necessarily results in the demoralizing and depoliticizing of public discourse. The point I’m makingis that US officials (like many others) were Machiavellian not just in terms of their use of napalm, but their approach to public discourse. And my crank theory is that one necessarily leads to the other.

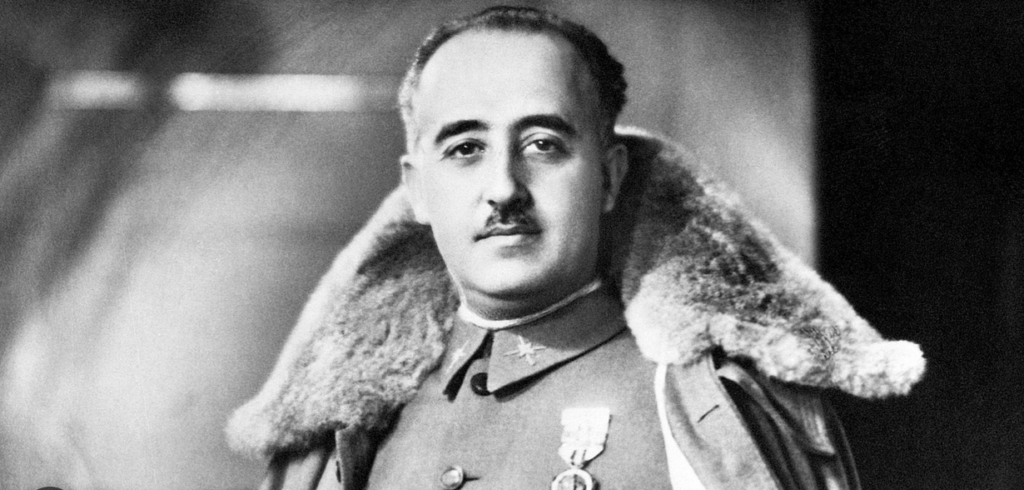

A lot of people are sharing this post, and it’s wrong. Students were tremendously supportive of Nazis. (I think they were also supportive of Mussolini and Franco, but I haven’t read much about them, so I might be wrong.)

More important, this post appeals to the fantasy that complicated political situations are actually simple. It says they’re really a binary between a group with perfect insight and the right understanding, and a ruling class that is a Disney villain. That way of thinking about politics shuts down our ability to argue with one another reasonably about policy options. As it is intended to do.

There are evil groups and evil policies, but, if I were going to say that there is a good law of history it would be: no framing of any major policy conflict as binary of two groups (one right and the other evil) has ever been just, accurate, useful, or helpful.

I’m open to counter-examples, but, since thinking about this framing of politics has been something I’ve been studying for forty years, I’m pretty confident that there isn’t one.

So, if you think you know of a time when a major policy issue was a binary between two sides–of two groups (one right and the other evil) –I’d love to hear about it.

Tl;dr the people who support a political figure who says, “I am so committed to the Real People that I will violate all legal and moral norms to enact my policies” always end up regretting it. Trump is very precedented, and it’s never worked out well.

I once had an unfortunate disagreement with a colleague whose work I so very, very much admire and have always supported. It came about because they kept saying that Trump and his actions are “unprecedented.” They were saying this for good reasons—wanting to mobilize outrage about Trump—but it is a historical claim, and, as such, it’s false. More important, it’s rhetorically (but understandably) misguided.

I think I came across as a pedant, crank, or someone who disliked their work. In reverse order, I love their work, and I am a crank and pedant, but, as it happens, when it comes to my insisting we not talk about Trump as unprecedented, I am neither.

His supporters believe he is unprecedented, and that’s one of the main reasons they support him. And they deflect any consideration of the precedents, as well as any criticism of him.

A lot of criticism of Trump has to do with who he is, and that kind of criticism helps him. All the evidence is that he is a corrupt, dishonest, racist, fiscally incompetent, and dishonest man who regularly sexually assaulted women, and who advocated insurrection. But there’s no point in emphasizing any of that when talking to his base because they agree that he is that person and did those things. They support him because he is a racist, corrupt, dishonest, rich person who gropes women. Most of them like that he is that person. They want to be him.

People who aren’t his base support him because they believe that they will benefit from the policies he’ll enact, especially “freeing” business owners and rich people from rules, restrictions, and taxes.

And there are people who will vote for him just because they have been trained to hate the hobgoblin of “liberals” by years of demagoguery. Some of them aren’t wild about Trump, and some have become wild about him because of the criticism. That kind of support is strengthened by the way that media and some scholars frame our vexed and complicated world of policy commitments as actually a third-rate reality show of a fight between “liberals” and “conservatives.” The single-axis model of policy affiliation depoliticizes policy argument, but that’s a book (which may come out fairly soon, fingers crossed).

Here’s the important point: just because that’s how the media frames something, and it’s possible to find supporting data, that doesn’t mean the frame is either accurate or useful. The media frames questions about birth control in terms of pro- or anti-abortion. It framed questions about the Iraq invasion as pro- or anti-war. Both of those policy disagreements are and were better served by acknowledging a a spectrum, rather than a single-axis continuum or binary.

The media frames all questions in terms of two identities at war (“left v. right”). To the extent to which media–even if they identify as “left”–frame issues in terms of identity, they help Trump.

There are a lot of reasons that people support Trump. People who rely on Fox News, the manosphere, Newsmax, for their information would vote for a cold turd as long as they were told voting for that turd would piss off “the woke mob.” Second, chiliastic fundagelicals love his aggressive actions in regard to Israel because they want nuclear war there–they believe it will reduce the number of Jews to 40k who will be converted, and thereby bring about Jesus’ reign on earth. That many Jews are choosing to support Trump because of his advocating policies that increase the likelihood of nuclear war in that region is just really frustrating. Third, descendants of immigrants pull up the ladder behind them. Unhappily, this has always been the case—the people most hostile to a new group of immigrants is the most recent group of immigrants. Fourth, toxic populism.

I think the first three are fairly clear, so I’ll emphasize the last.

Populism says that our world is not complicated, but actually a zero-sum battle between an elite and the real people. It says that we don’t have reasonable and legitimate disagreements about policies. It says that the correct course of action is obvious to all real Americans/Christians/workers/conservatives/whatevs. [1]

Commitment to a populist leader is generally irrational. Populist leaders say there is a real us, and that all our problems are caused by Them. They say that we can solve all our problems by fanatical commitment to the in-group, and refusing to listen to any criticisms of the in-group. The first move of toxic populists is to ensure their base dismisses as “biased” any criticism of them. They do so by demonizing (they’re evil), irrationalizing (they’re motivated by feelings, but we’re motivated by reason), and pathologizing (they’re lazy, criminal, corrupt) any source that is not fanatically committed to the leader/group.

Trump is a toxic populist.

The proof is that, if you say this to any of his supporters, and give the definition of a toxic populist, they won’t engage your argument.

Their first move will be whaddaboutism, their second will be deflecting the definition on the grounds that, since it applies to Trump, it must be “biased” (they’ll probably say “bias”), their third will either be harassing you (they like signing you up for Ashley Madison) or blocking you.

Claiming that Trump is unprecedented confirms his supporters’ belief that there is no already existing evidence that what he wants to do is politically, ethically, and economically disastrous. It enables them to deflect comparison to Castro, Chavez, Erdogan, Franco, Hitler, Jackson, Mussolini, Putin. Claiming that Trump is unprecedented saves them from the rhetorical responsibility of showing that supporting someone like Trump has worked out well. (Narrator: it hasn’t, especially for the working class, but even for plutocrats.)

Not all Trump supporters are the same, but the narrative that he is unprecedented enables every one of them to keep from thinking about the long-term consequences of their support. But, as I said, he’s following a playbook. It isn’t restricted to “right-wing” (I hate that term) leaders. What’s wrong with Trump isn’t about left v. right. It’s about whether a political leader values and honors democratic and legal norms or argues that he (almost always he) shouldn’t be held to them because reasons. And a leader who has made that argument has never worked out well.

Many of his supporters, like people who have supported authoritarian governments in Central Europe, are wealthy people who believe that they will profit from an authoritarian anti-socialist government. In Russia, they supported Putin, and they were wrong, as shown by what Putin did to the economy, and by the number of plutocrats who fell out of windows and landed on bullets. Paradoxically, capitalism requires innovation, and there isn’t much of that in an authoritarian culture. Authoritarian cultures/governments that have been profitable have done so by stealing ideas and innovations from democratic ones (e.g., printing or weaving).

But, and this is the important point, there are other examples of times when the people with a lot of monetary power backed a charismatic leader who was openly advocating an authoritarian government, and it didn’t work out well for them. There are precedents, and they show that charismatic leadership is actually a really bad way to run an organization, let alone a country.

The question Trump supporters should be asked is: when has support of this kind of political figure worked out well?

And that is the only aspect of Trump that is unprecedented.

[1] For a long time, I was averse to calling this “us v. them” false way of thinking about politics “populism.” I thought it should be called “toxic populism.” But, that train has left the station. Still and all, I’d argue that there is a difference between “our current political situation hurts these groups that don’t have a lot of political power” [what I think of a kind of populism—trying to worry about the ramifications of our policies on people not in power] and the binary thinking of toxic populism (our complicated political situation is actually a simple binary between people who are good/honest/real/authentic and Them). The best short book on populism is Jan-Werner Müller’s What is Populism. The best thorough work is the Oxford Handbook on Populism.

I often read a subreddit AmItheAsshole. People write in describing some incident where they think they were right, but someone tells them they behaved badly, and they’re asking for judgment.

For instance, there was recently a post by someone who said that his girlfriend dithered and delayed in the morning, and therefore regularly drove well over the speed limit in order to get to work on time. The Original Poster (OP) told her that her speeding was unsafe, and that she should get up earlier. She ignored him. She got a lot of speeding tickets. When she had gotten so many speeding tickets that she was about to lose her license, she told the OP that he should claim he was driving her car at the time of the last ticket–that he was the one speeding. That would cost him a lot of money (directly and indirectly) but it would enable her to keep speeding, since she could keep her license. He refused. She said he was the asshole because now she would not be able to drive to work. She told him that he would have to drive her to work, since he had caused this situation. He refused.

He was unwilling to take the hit of increased insurance rates and having to drive her to work just because she had ignored everything he warned her about, and had chosen to make really bad decisions. She said he was the asshole, since her current situation—having to take public transportation to work—what the consequence of a decision he’d made.

So, who is the asshole?

AITA is really a subreddit about blame and responsibility, and commenters are invited to make one of several judgments: YTA (you’re the asshole) meaning you, and you alone are responsible for this situation. In other words, the OP is responsible for her losing her license. Or, there’s NTA (not the asshole) meaning that there is an asshole (a person whose bad behavior led to this situation) but it isn’t the person who posted the question (for instance, the girlfriend who dithers in the morning). NAH (no assholes here) meaning that it’s a bad situation but not because anyone behaved badly. ESH (everyone sucks here) meaning that this situation came about because everyone is awful.

Clearly, she hadn’t learned from this situation. She had no intention of driving any differently. She didn’t see the consequences of her behavior as…well, the consequences of her behavior. She thought someone else should step in and save her, so that she could continue to be irresponsible. Technically speaking, OP could have kept her from losing her license. But she would never have been in that situation had she been more responsible about her time management.

I taught college writing for about forty years. And, when I was the teacher of record, I sometimes had a student who was flunking my class (because they hadn’t turned in any work, they’d plagiarized, what they did turn in had little relation to the assignments, and so on), and they would say to me, “If I flunk this class, I’ll be kicked out of college; because of you, I’ll be thrown out of college.” Technically speaking, my flunking them might be the final straw, and so, if I didn’t flunk them, they could stay in college, until they flunked the next class.

But, if they hadn’t flunked (and weren’t flunking) lots of other classes, what grade I gave them wouldn’t matter. What I did only mattered because of the situation they’d gotten themselves into. I didn’t force them to flunk; I didn’t keep them from doing the work. Like the girlfriend who regularly violated speed limits, the situation they were in–about to flunk out of college–was the predictable consequence of choices they’d made.

The claim that Democrats are responsible for the House impasse reads to me like an AITA post. So, imagine that the Republicans claiming that the House inability to get any work done is the fault of the Democrats wrote in to AITA. What would the judgment be?

Demagoguery means reducing complicated, nuanced, and uncertain policy issues to questions of fanatical loyalty to us (including refusing to look at any non-fanatically in-group media) and Them (everyone else). Demagoguery means refusing to compromise. The GOP has promoted an anti-government demagoguery since the 80s. The basic message of that demagoguery is that the government is the cause of all problems, so shutting down the government would be good. No reasonable person believes that, but it’s been a winning frame for the GOP. So, they’ve spend forty years promoting it.

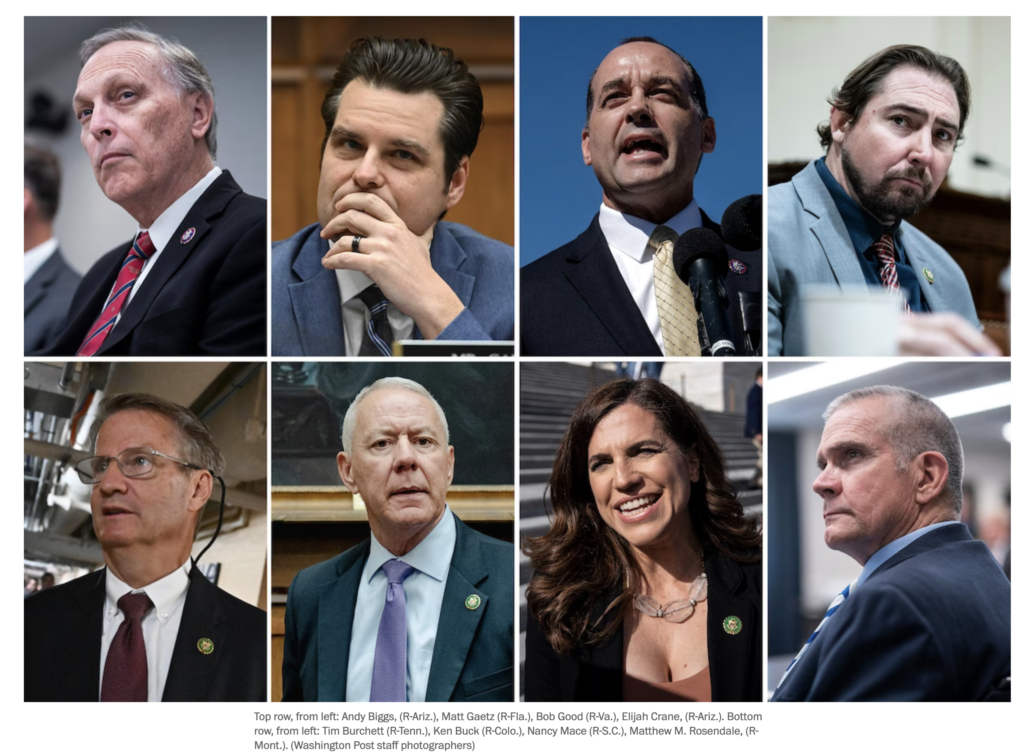

The GOP decided to engage in a kind of gerrymandering that meant that winning a primary rewarded the most demagogic candidate. The GOP (and its media enablers) decided to reward demagoguery. The GOP decided to refuse to hold its most demagogic members accountable for anything, ranging from an attempted to coup to sex-trafficking underage girls.

And now, having enabled the election of people who think refusal to compromise is a good thing, whose policy agenda is entirely negative and fairly incoherent, and who couldn’t reason their way out of a paper bag if both ends were open and there were flashing EXIT signs, but who are fanatical and in districts that would elect a dead dog if it had R next to its name, the GOP is realizing that they’re held hostage by unreasonable people.

And they think the Dems should save them.

That girlfriend thought the OP should take the hit. She thought he should lie, take the insurance hit, and pay the fine, so that she could keep speeding.

So, who is the asshole?

I’ll start with my thesis, which I don’t usually like to do. Banning drag shows, or criminalizing people in drag (or trans people) interacting with children, isn’t a policy advocated by people for whom preventing the raping or sexualizing children is the highest priority, or even an even very high priority at all. Were they actually concerned about sexualizing and raping children, then they would be up in arms about what is happening in Christian churches. They aren’t because they aren’t.

They don’t actually care very much about raping or sexualizing children, as long as it’s done by in-group members. The best proof of that fact is that no one outraged about drag performers will read any more of this post, nor will they look at the data on sexual abuse in churches. If they really cared about sexual abuse, they’d want to know what causes it.

They don’t because they don’t.

I spend a lot of time drifting around various spaces on social media, and I try to get people to explain their position on various issues.. (Since so many people use social media simply to show they hate the out-group, that’s not easy.) I’ve never managed to get anyone to explain why they worry more about drag queens than about the people most likely to rape children. Most child abusers are religious, as even the very conservative Missouri Synod admits. Were people outraged about drag queens actually concerned about sexual exploitation of children, and I think we all should be, then they would have been demanding changes in major churches, like the SBC , evangelical churches , or the Catholic Church, which still isn’t managing the accusations responsibly . The SBC, like the Catholic Church , hid its sexual abuse problem for years , and “conservatives” helped them do so .

So, why, instead of trying to enact reasonable policies that deal with what is actually the problem, are people passing laws about drag queens?

They never explain that.

I’ll emphasize that point, since every person with whom I’ve engaged on this issue, or the rhetors I’ve read, never explain why we should care more about a group that has no record of sexually abusing children than the group with the highest incidence of actually doing so.

I know why, but I’d like them to admit it. They care more about preserving the reputation of their in-group than they care about in-group members raping children.

That’s really it in a nutshell, but I think there are other ways of thinking that help them rationalize that privileging of in-group loyalty over raped children.

It seems to me that there are several factors 1) binary thinking about sin; 2) rigidity about categories and order, so assuming that easing up on any of the categories of any kind will lead to chaos; 3) privileging in-group loyalty over anything, including principles, logical arguments, what Jesus said; 4) believing that “cross-dressing” is a sexual kink, and so drag queens are sexually stimulated when reading to children 5) s strategic deflection; 6) desperate deflection.

1) Binary thinking. As even G.K. Chesterton said, people have a tendency to flatten sin, and so assume that engaging in one sin necessarily leads to them all. So, if you do one of the sins, you do them all. That fallacy means that people assume that a person who is trans or dresses in drag is violating a gender norm, and therefore must be violating all the sexual norms. On the contrary, child molesters are likely to be Christian, active in the church, and very nice.

2) Fundagelicals are binary thinkers, and so they believe that a person is either saved (in-group) or a sinner (not in-group). The way that they decide that someone is in-group is that they are loyal to the in-group—they say the right things, are nice to the right people, claim to have the same values. A person gets “moral license” by being a member of the group, and therefore any of their transgressions are forgiven, regardless of how often they transgress, or the consequences of their transgression. And, for them, “forgiveness” means “pretending it never happened” and therefore never mentioning it again.

In other words, at least in my experience of how “conservative” Christians explain how their moral standards work, it’s all about in- v. out-group, and not able holding everyone to the same standards.

3) It’s interesting to me the way that “conservative” “Christians” flatten transgressions, ignoring the question of harm. This flattening became clear to me when Daniel Lavery (a trans man) exposed that, not only was his brother sexually attracted to minors, but he was being protected by the leader of the church, and put in positions of working with children. The leader of the church was Lavery’s father. He had long known that Lavery’s brother was sexually attracted to children, and yet had kept him in a place where he was regularly interacting with children, and had not divulged that information to anyone in the church. When Lavery confronted his father, his father said something along the lines of, “Who are you to judge? You’re violating sexual norms too.”

Lavery, an adult engaged in consensual relationships with other adults, was treated as just as bad as someone who wanted to molest children.

While both being trans and wanting to molest children are transgressions, as far as Ortberg was concerned, they are not the same in terms of harm. If John Ortberg actually and genuinely cared about child rape, he would deal with the massive beam in his own eye. Were “conservative Christians” genuinely concerned about child molestation, they would clean their own house before they went after drag queens reading in a library. They don’t because they don’t.

4) Fundagelicals care more about drag queens than in-group child rapists because they can dismiss the in-group child rapists as exceptions. Upstanding church member child rapists are exceptions to the rule—there are far more upstanding church members who aren’t child rapists. Which is true. But why not use that same math for drag queens?

This is the point that makes it clear that their obsession with drag queens is irrational. It’s just deflection.

So why are drag queens more threatening than the actual child rapist in your church? Because they call into question rigid notions about gender.

5) It seems to me—and this is just based on my sometimes drifting into that world—that they believe that drag queens point out that our notions of gender are open to discussion. (Anyone even a little bit aware of the history of gender knows that, but these people refuse to admit that their categories of gender don’t match biology, let alone the variety of cultural norms. I’ve had this argument with them.) As far as I can tell, they have the sense that if we ease up on the categories in this binary about gender, then we’ll have no categories at all, and all hell will break loose.

It seems to me very similar to pro-segregation rhetoric.

It’s just fear of change, an inability to deal with nuance, and a refusal to think about the world in terms of anything other than rigid categories.

Child rapists don’t call into question gender norms, and, and I’m not kidding, many people therefore seem to find it easier to normalize child rape than they do drag queens.

6) Their only experience of something like drag queens is sexual (cross-dressing as a sexual kink), and so they assume that drag queens are turned on by being in front of children.

This is one of those arguments that seems to me shows more about the person making the argument than I really wanted to know.

It’s like someone saying we shouldn’t have shoe stores because some people get turned on by handling women’s feet. Anyone who makes that argument is someone very attached to the notion that handling feet is sexually stimulating. They think a lot about feet.

Every once in a while, someone will point out that a gay couple was accused of molesting a child, or that someone in drag did something bad. I’m sure that gay people and drag queens sometimes do something inappropriate, but the numbers of them who rape children is miniscule compared to the number of self-identified Christians who rape and sexualize children.

Jesus once said stop worrying about the tiny thing someone else is doing, and worry more about the big thing you’re doing.

And, really, that’s what all this comes down to. This isn’t about drag queens; this is about deflecting and projecting the epidemic of sexual abuse in Christian churches.

People who follow Jesus should worry more about the sexual exploitation of children that we Christians are doing, since it is so much more than what drag queens are doing. Unless we don’t really care about children, and don’t really care about what Jesus said.

And, yeah, that’s my experience of “conservative” Christians–they don’t really care about children, and they care even less about what Jesus said.

I’ve spent a lot of time arguing with Stalinists (I was in Berkeley for many years), and no one so much reminds me of arguing with them as arguing with Trump supporters. Neither Stalinists nor Trump supporters could (or can) reasonably engage opposition arguments. In fact, like Stalinists, Trump supporters refuse to look at anything written by someone who doesn’t fanatically support Trump. Because, like Stalinists, they think that “being rational” means “being fanatically committed to our leader.” They ignore that people who actually have a rational/reasonable position can make an argument that responds to the best opposition arguments.

I’m happy to engage in a reasonable discussion with any Trump supporters who did read this far.

(That would be zero. If I’m wrong, please let me know.) So, this post is about how to think about how Trump supporters argue.

I grew up in a family of arguers, and it sometimes ended up in violence. But it didn’t always end there, and so I got interested in the relationship between argument and violence pretty early on.

For reasons too complicated to explain, I ended up taking rhetoric classes. In those days, the Berkeley Department of Rhetoric was (I now understand) very oriented toward neo-Ciceronian understandings of rhetoric—that is, what might be called responsible agonism. It’s rhetoric as the area (not discipline) of responsibly engaging the best opposition arguments.

And so, since I was in Berkeley, I spent a lot of time arguing with the four kinds of communists (who spent most of their time breaking up each other’s meetings), as well as Libertarians, Republicans, liberals (we can improve things through incremental changes), various kinds of environmentalists, constructivist and essentialist feminists, and everyone except Moonies (since they wouldn’t argue, or even admit they were Moonies).

I think I learned the most about argument by arguing with Stalinists. Maoists and Trotskyites didn’t even try to argue with me—once they found out I disagreed, they just said, “Come the revolution, motherfucker, you’re the first one up against the wall.” It’s weird how often I was told that.

What I think of as “Stalinists” didn’t call themselves that—maybe Leninists? I’ve forgotten the terminology—but they defended every single thing the USSR did. It could do no wrong. As it happens, for complicated reasons, I had visited the USSR in 1974 (or so, maybe 1973?), and I had no love for the USSR. It would take me another twenty years to find the terminology to describe what they were doing (demagoguery), but the short version is that if the USSR was accused of doing something wrong—if I said I’d actually seen something, or there was an documented event—they refused to think about it. Anything that might complicate their commitment to the USSR, they dismissed as anti-USSR propaganda.

They said it was, so to speak, fake news.

They were suckers. Anyone who refuses to consider evidence that they might be wrong is a sucker.[1]

Sometimes the Stalinists would argue with a bit, but they too would eventually say, “When the revolution comes, you’re the first up against the wall, motherfucker.” In other words, because they couldn’t defend their position rationally, they resorted to threatening me.

They couldn’t defend their position reasonably because it wasn’t a reasonable position. And that’s why they had to resort to threatening me.

That’s why so many Trump supporters threaten or harass anyone who disagrees with them. That’s why so many gun nuts threaten or harass anyone who disagrees with them. That’s why Trump supporters end up shouting at people over Thanksgiving dinner. Because they can’t argue any better than a Stalinist—because, in fact, they can’t argue in a way that responds reasonably to critics of their position. If you can’t respond reasonably to your best critics, you have a bad argument.

What Stalinists couldn’t do (and Trump supporters can’t do) is hold themselves, their in-group, or their in-group arguments to the same standards they held/hold anyone who disagreed with them. That’s what it means to have a rational argument—not that you have a calm tone, or that you have data, but that you hold yourself and your opposition(s) to the same standards of proof and logic as you hold yourself. The way I got Stalinists so mad was pointing out that they held themselves to lower standards than they held others’ arguments. And that’s why Trump supporters get so mad at me now. They’re mad that I’ve pointed out that even they think their argument will fall apart if they have to treat opposition arguments reasonably.

In other words, Trump supporters (like Stalinists) agree with me that they can’t defend their arguments reasonably. And that’s why they engage in ad hominem, motivism, whaddaboutism, and threats.

The difference is that Stalinists didn’t care if they were reasonable. Like Trump supporters, they were clear that they held their beliefs because those were the beliefs of their group—they believed what it was loyal to believe, and they refused to consider any data that might complicate their loyalty to Stalinism. Trump supporters similarly believe what it’s loyal to believe in order to support Trump, and they refuse to look at anything that might complicate their fanatical loyalty. But Trump supporters claim to follow Jesus.

Jesus said, “Do unto others as you would have done unto you.” Trump supporters rage when their position is misrepresented, when people make fun of them, when people cite bad data, when he is treated as they wanted HRC or do want Hunter Biden treated. They rage at “libruls” who, they say, live in a propaganda bubble.

So, do they treat others as they want to be treated?

Nope.

Were Trump or his supporters followers of Jesus, then they would never misrepresent others’ positions, lie, cherry-pick, refuse to engage the smartest opposition, or argue as they do.

Trump supporters reject Jesus because they worship someone who treats as others as he doesn’t want to be treated, and their worship of him means that they treat others as they don’t want to be treated.

There are two ways to make a Trump supporter incoherently, foaming-at-the-mouth, pound on the table mad: 1) ask them if their commitment to Trump is open to falsification—what evidence would cause them to reconsider their commitment? 2) ask them if they are willing to hold their out-group(s) to the same standards they hold Trump.

They get triggered because they’re very sensitive. While they have a position they can, in their minds, support with lots of data, even they know that their arguments are such fragile gossamer that they disappear if touched with the slightest breath of a reasonable opposition argument.

Here’s how Trump supporters can prove me wrong: they link to sites that support Trump and engage the opposition arguments as they want their arguments treated, arguments that hold themselves and others to the same standards of evidence, proof, and logic. Or they PM or email me to have a reasonable discussion.

Here’s how Trump supporters prove I’m right: they attack me personally, harass me, make an argument about “libruls,” or otherwise admit that it isn’t possible to support Trump and follow Jesus’ rule about treating others as they want to be treated.

Maybe they should think about that. Jesus didn’t mumble.

[1] That doesn’t mean we have to consider every piece of evidence that contradicts what we believe.