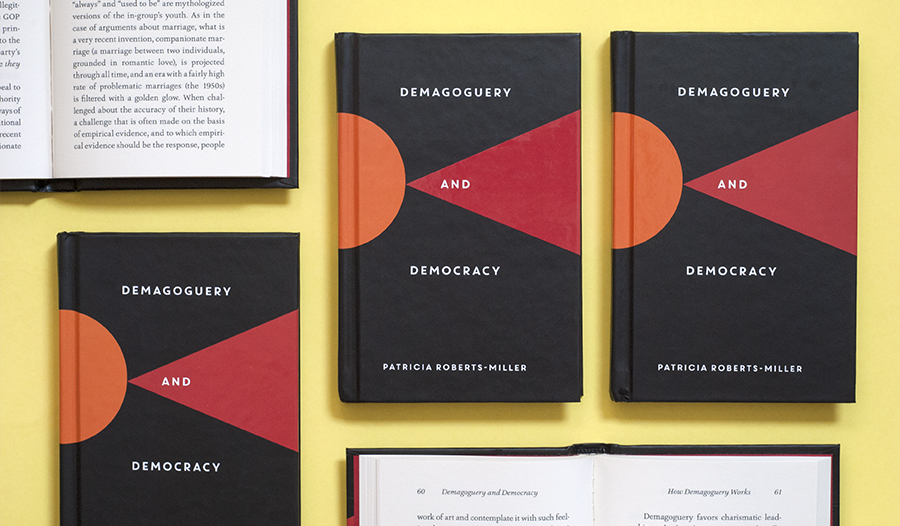

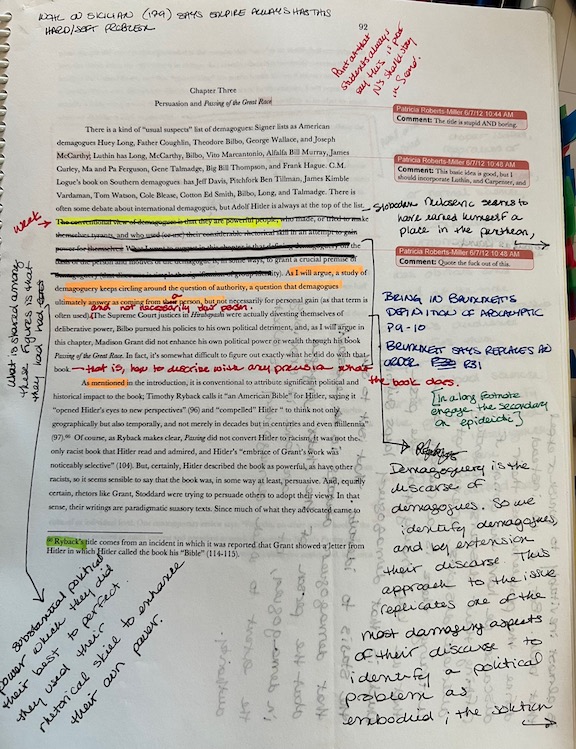

[photo of a page from the 2012 version of Rhetoric and Demagoguery]

I’ve written elsewhere a lot about procrastinating…

…in the draft of a book I never finished. I put off finishing it.

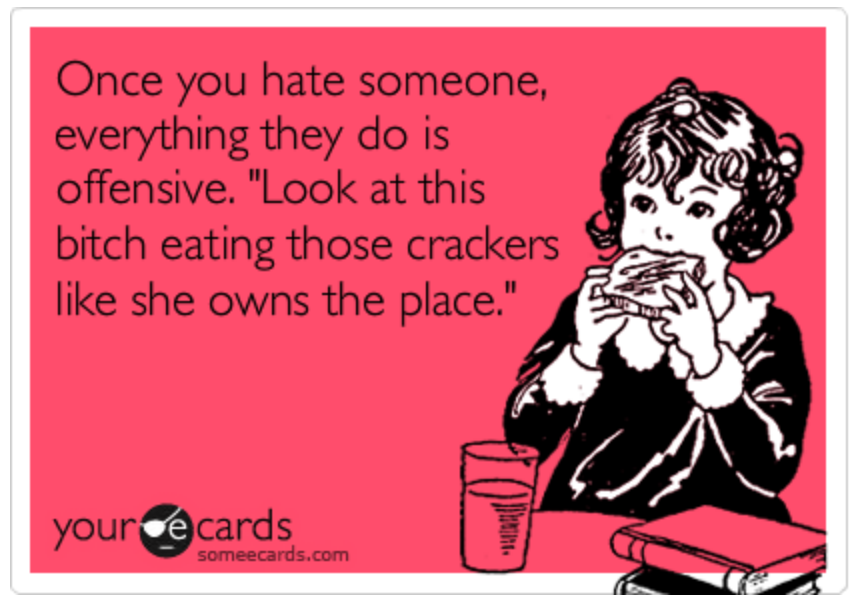

We have a tendency to personalize everything, from politics to writing process. By that I mean that we talk in terms of identity rather than behavior (“I’m a procrastinator” instead of “I procrastinated finishing that book”). We really need to stop. Behavior doesn’t have a necessary connection to identity. I procrastinate, and have a lot of half-finished projects. But, I’ve published six books and over a dozen peer-reviewed articles in my career, and six book chapters in the last three years alone. So, I procrastinate, but I also get things done—the two behaviors aren’t mutually exclusive.

Let’s be clear: I made some bad errors in my career, but they weren’t because I’m a procrastinator. I wasn’t procrastinating. I was working like the Tasmanian Devil in the Looney Tunes Cartoons. My errors were, or were the consequence of, being bad at time management, having unrealistic notions about publishing, not having mentors who could give me field-specific publishing advice, not being in a relationship that was supportive of my career, pissing off a powerful realist in the Philosophy Department, and many other things I probably can’t name.

Everyone procrastinates, in the sense that not everyone gets everything done right now—you can’t. Procrastinating means putting some things off till later, and, since we can’t actually do everything right now, putting things off is often a good time management strategy. I never finished the book about scholarly writing because other projects (about our current political moment) seemed to me more urgent. They were. They are. When we have people over to dinner, we don’t set the table till the last minutes. We have cats.

Sometimes procrastinating isn’t a good strategy. It can be a kind of self-sabotage; it can mean getting caught a terrible loop of shame. I think a lot of self-help rhetoric ensures that people get caught in that loop. It says that there is a simple solution, and you should follow it. Since there isn’t a simple solution for how hard it is to write a dissertation, then people for whom the simple solution doesn’t work think they’re the problem. They aren’t. The simple solution is the problem.

There is no simple solution for how hard academic writing is.

Also, the Easter Bunny was your parents. And I have bad news about Santa Claus.

One way to try to distinguish sensible v. self-sabotaging procrastination is to try understand why we’re putting something off. And those ways work differently, I think, for what kind of writing people are trying to do. This post is for scholarly writers who believe that their procrastination is hurting them.[1] In fact, it’s for a specific way that a specific motive for procrastination might be hurting them. In other words, I am not laying down rules that will work for everyone under every circumstance.

Putting off a project can be a savvy time and career management choice if the project requires resources we don’t have (e.g., travel money, fluency in a specific language), is less urgent than something else (e.g., it won’t count for promotion or tenure, won’t be part of a dissertation, or, in my case, is a less urgent argument to make given our political situation), or in various other ways isn’t something we should be pursuing right now.

My personal crank theory is that the unproductive kinds of procrastination, and the unproductive ways of trying to stop procrastinating, all involve shame. But people who’ve done actual research on this say that the unproductive kind of procrastination tends to have one of three triggers: drudgery, existential threat, decisional ambiguity.

And here I want to stop for a moment and point out that writing a thesis, article, or book has every single one of these three triggers and way too much shame, and often way too many advisors who think shame and panic are necessary to the writing process. That’s how those advisors work. That isn’t how you have to work.

Most of the advice out there about procrastination assumes that the trigger is drudgery, and so, if that’s your problem, google away. Lots of strategies —the emergent task planner, giving yourself rewards, breaking things down into manageable steps, telling yourself you have to do either [whatever it is] or a more unpleasant task [e.g., clean the litterbox]–are great advice if that’s your motive for procrastinating.

There’s less about existential threat. This is a pretty good article about that trigger. The short version is that the more we succeed, the more likely we are to worry that we will be exposed as imposters. (The only people I’ve ever known who didn’t have imposter syndrome were narcissists, and were, in fact, imposters.) The temptation is to engage in self-sabotage (e.g., get involved with a high-maintenance partner who doesn’t support your career, take on too many responsibilities) so that it’s always possible to say that no manuscript was your best effort. Therefore, if it’s trashed by someone, that isn’t actually an indication of whether you are a smart and good person.

Weirdly enough, outright failure can be less threatening to our self-esteem than trying hard and turning out something that gets a lot of criticism, or doesn’t have the impact we’d hoped, or is otherwise okay but not great. (I’ve often thought that it was a kind of gift that I have never been the smartest person in my family, friend group, work group, any class I’ve taken, or just about any group larger than me and one of my dogs, and not always then. I still had/have imposter syndrome, but there was always less at stake for me.)

The most effective way to manage this kind of trigger for procrastination and other forms of self-sabotage is therapy. (Ideally with someone who has worked with other academics.) I can’t say that strongly enough.

I want to focus on decisional ambiguity because I think it’s the least-discussed in resources for academic writers. That trigger occurs when we’re pressed to make a decision that we could make in a relatively straightforward way if we had information we don’t have at this moment. The situation is ambiguous, but it could be clear if we had certain information. The impulse is to delay the decision until we get that information.

Just to be clear, that can be a good choice. A very popular book advocates a method of setting aside decisions till you have more information (Getting Things Done).

But, when writing a dissertation or book, while teaching, having service requirements, we can find ourselves suffering from decision fatigue. The tl;dr version is that we make decisions better when we have a limited number of them we ask ourselves to make. If we have to make too many decisions (and “too many” depends on all sorts of factors), then we just stop making decisions, or start flipping coins.

So, what does that mean for scholarly writing?

If you’re writing a book, thesis, article, grant proposal, or anything else in a scholarly genre, then, even in the first draft, you’re faced with too many decisions. Is this the right organization, should I move this argument there, should I read that [article/book], am I representing that argument fairly, what the hell is my point, should I use this word, should I drop out of grad school/academia, maybe I should read that other [article/book], am I explaining this point, is that the right quote, how much should I cite that [article/book], have I cited this source correctly, will my readers hate/love this, and so many other decisions that range all over the place: your argument, your readers’ possible responses, your relationship to others who’ve written about this, your career, the job market, the text you’re producing (from sentence-level correctness to genre questions).

A lot of conventional writing process advice is useful: expect to have multiple drafts, and begin by focussing on big picture issues (wtf is my argument before you worry about what tense you should use); expect that writing is recursive (so that when you think you’re at editing stages, you might find that trying to correct passive agency or a mixed metaphor might make you rethink important parts of your argument).

It also means: limit the decisions you need to make on any given day.

Decide ahead of time that you’re going to spend certain times in the week writing—don’t leave that till the day. And then, when you’re in that writing time, it might mean that you write a blathery draft in which you don’t try to get much of anything right. (In a first draft, I often have sentences like, “As Blarghy McBlarghy said, democracy depends upon interlocutors blarghing with each other while focused on blargh.” Or it might be, “As Shirer says in that book with the blue cover, Hitler was [effective? that’s the wrong word])”

One friend described “the narcissistic pleasures of the first draft.” Don’t try to get your argument right; decide you’re just trying to get your thoughts—fuzzy, incoherent, rambling, passionate–in writing.

I never have a strict outline at this point (actually I never have a Ramistic outline ever), but I sometimes (not always) have a flow chart of the four or five concepts/cases I want to discuss. It’s never what the structure actually turns out to be. So I don’t decide on an order of ideas as much as throw out a possible order.

It’s like planning a road trip—you throw out the places you’d like to see, and make a guess as to what route makes sense. But, as you travel, you change your mind about where you want to go. You follow the evidence.

The next pass is deciding that I’m going to try to get my argument somewhat more clear. This means that I reread what I’ve written in a purely critical mood (deciding what’s not working, but not trying to decide what would make it better). Sometimes I use different colored pens, or different colored post its. There are: sentence-level gerfuckedness (orange or red), parts that require more research or bringing in research (green), significant rewriting but the argument is good (blue), changes in wording I know are right (black).

Sometimes I don’t do it that way, and each color is a different pass on reading. So, all the comments I made 1/3/2020 are in pink; the ones from 2/15/2021 are in blue. (In other words, don’t get too rigid about your process, or you’ll have too many decisions to make, and too many ways to shame yourself.)

Loosely, my method is: blather, then critique, then blather oriented toward responding to the critique, then critique. Rinse and Repeat. Do that till you’re working on the Works Cited.

And it’s generally working from big picture (WTF is my point) through issues of organization and citation to paragraph to sentence. But it’s pretty common that I hit a “sentence-level” issue (e.g., do I mean “contact” or “impact”) that causes me to rethink important parts of my argument—from the underlying model (in other words, my argument) to organization.

I’m not saying that people should do what I do. That’s pretty much the opposite of my point. I don’t know anyone else who uses this specific method. I’m describing it precisely because I think it wouldn’t work for most people—I’m hoping to inspire people to come up with one that works for them, even if it seems weird.

I’ve long been grumpy that research on the writing process turned into writing procedures [I’m looking at you: mental mapping.] My point is that one way to get around the trigger of decisional ambiguity is to restrict the choices you’re making at any given time. A decision you should not make in the moment is how you will do that.

Everyone should have a day they do not work. (I broke this rule about four times a semester when I had to grade papers, but I tracked my time, so that I got that time back for vacation.) Work needs to have limited space.

There are some other strategies that people find useful. One is sometimes called ‘chutes and ladders.’ When you don’t have the cognitive capacity for the choices that also trigger existential threat, you make the decisions that procrastinate and yet enable that kind of decision. Before leaving your workspace (and, really, try to have a workspace—I know it’s hard; at one point in grad school my workspace was a closet), pull up on your computer (or have piled on your desk) the sources you think you should use (the Blarghs). Or, before you walk away from that space (and you do need to walk away), write out a sentence or two of what you hope to write the next time you’re back to work.

Limit your work time. But, when you’re working, actually work. And give yourself breaks (about ten minutes of every hour). Some people leave a note to future self—here’s what I did, and here’s what I hope to do next.

If there are other decisions important to your writing, then set them up for yourself before leaving your workspace—cue up the playlist, put the coffee in the fridge, set up the coffeemaker, move the shaming books/articles away, organize your pens, clean off your desk, make sure the cat’s bed is up to your cat’s standards.

And procrastinate. Put off till later worrying about whether your advisor or the press or the journal will like what you’re writing, what the response to this book will be, whether it will get you a job or tenure.There are times for worrying about all those things, but not while you’re trying to write the first (or even third) version of your thesis/article/chapter/book.

We procrastinate setting the table because our cats will step all over the plates if we turn our backs. But we do eventually set the table. And we do so before the guests arrive.

Procrastination can be your friend. It can be a sensible way to think about what to worry about now, and what worries to deflect till later. But you do need to get your dissertation done before the guests arrive.

[1] Obviously, not because I think other kinds of writing are less important, but, especially when it comes to decisional ambiguity, the decisions are different.