On April 18, 1965, The New York Times published a long editorial written by Hans Morgenthau, in which he argued that, while he appreciated a recent statement of LBJ about Vietnam, on the whole, he thought that “the President reiterated the intellectual assumptions and policy proposals which brought us to an impasse and which make it impossible to extricate ourselves.” The assumptions were false, he argued, and the policies grounded in those assumptions were therefore unreasonable and unlikely to succeed. Morgenthau’s criticism of US policy in regard to Vietnam is interesting not because it was unusual (it wasn’t), but because the response to his criticism exemplifies how people avoid the responsibilities of democratic deliberation through motivism and fallacious arguments from association. That kind of response undermines useful policy deliberation, and ultimately contributes to authoritarianism. It doesn’t matter who it is used by or for.

Morgenthau was anti-communist, self-identified conservative, and one of the founders of what is generally called the “realist” school in international relations (e.g., Kissinger’s realpolitik). Thus, Morgenthau granted that China should be contained, but he argued that military intervention to prop up the Diem regime was not the way to do it. He argued that it was a fantasy to think that it could be contained in the same way that the USSR had been in Europe–that is, through “erecting a military wall at the periphery of her empire.” He insisted that the Vietnam situation was a civil war, not “an integral part of unlimited Chinese aggression.”

In many ways, Morgenthau’s criticism of US policy was more or less the same as others elsewhere on the political spectrum (like Henry Steele Commager, MLK, Reinhold Niebuhr). He said that Ho Chi Minh “came to power not courtesy of another Communist nation’s victorious army but at the head of a victorious army of his own.” (so this was not like Soviet aggression in Europe). Ho Chi Minh had considerable popular support, whereas Diem did not, and therefore this was not a military, but a political, problem. Morgenthau argued that, “People fight and die in civil wars because they have a faith which appears to them worth fighting and dying for, and they can be opposed with a chance of success only by people who have at least as strong a faith.” Supporters of Diem did not have at least a strong a faith because Diem’s policies resulted in his being unpopular (“on one side, Diem’s family, surrounded by a Pretorian guard; on the other, the Vietnamese people”). Morgenthau pointed out that trying to treat such situations in a military way–counter-insurgency–had not worked. The French tried it in Algeria and Indochina (i.e., Vietnam), and it didn’t work, and it wasn’t working for the US in Vietnam. Like other critics of US policy in Vietnam (e.g., MLK), he emphasized that Diem (and the US, by supporting Diem) had violated the Geneva agreement, especially in terms of refusing to have an election—a refusal that was an open admission that communism was not imposed on an unwilling populace, but a popular policy agenda (he notes, largely because of land reform). We were violating the fundamental characteristic of democracy—abiding by the results of elections—in some mistaken notion that it would protect democracy.

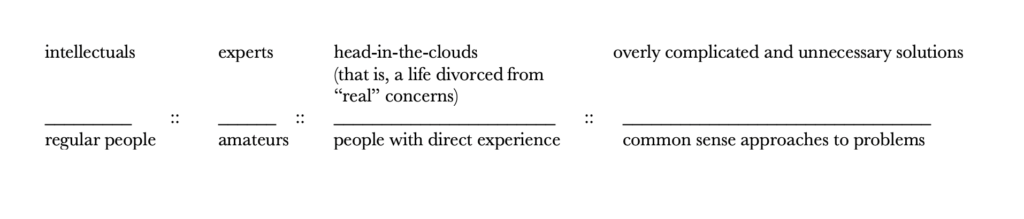

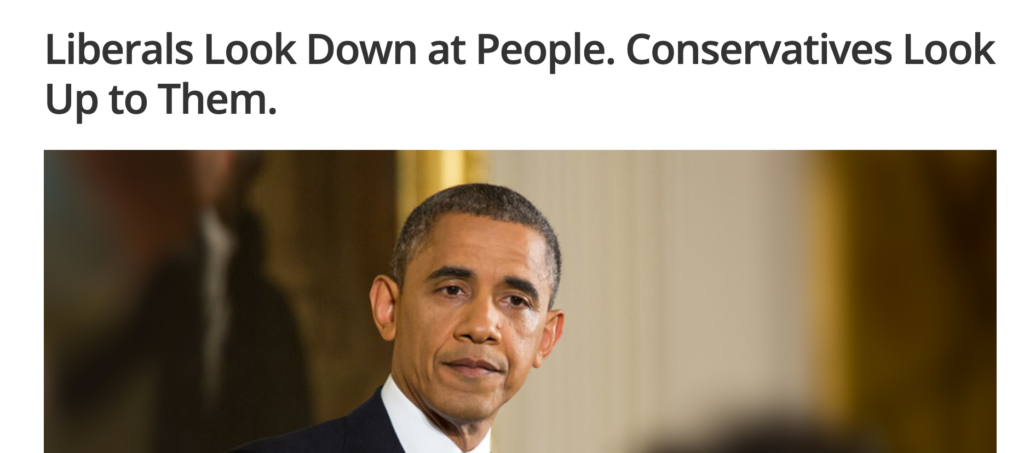

Morgenthau’s anti-communist, conservative, and realist opposition to Vietnam shows how false is our tendency to talk about policy affiliations in terms of identity (left v. right, “conservatives” v. “liberals”). To take a policy affiliation and assume it has a necessary relationship to an identity is anti-deliberative, anti-democratic, and proto-demagogic, and what happened to Morgenthau shows just how damaging that deflecting of argumentation is.

Being opposed to US policy in Vietnam didn’t necessarily mean that one was sympathetic to communism—it could, as it did with Morgenthau, be the consequence of such a commitment to anti-communism that one only wants to support polices that will actually succeed. Ironically, that would eventually be the position that Robert McNamara, the (liberal and Democratic) architect of US policy in Vietnam, would adopt. In his 1995 book In Retrospect, McNamara would say that he came to realize that everything people like MLK, Morgenthau, and Neibuhr had been saying was true. He didn’t mention them by name, or acknowledge that he could have listened to them. But he could have.

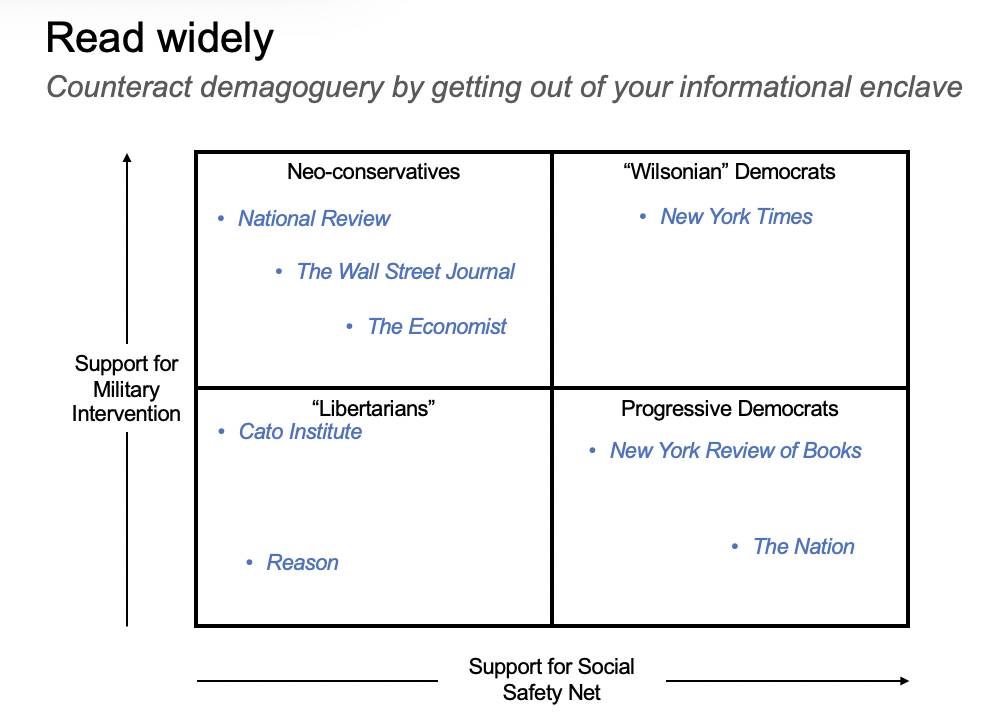

We now often equate opposing the Vietnam War with “liberals” and supporting the war with “conservatives” and we assume that “liberals” were Democrats and “conservatives” GOP. We do so, not because we’re operating from any coherent mapping of policy affiliation, but because reducing policy affiliation to a false binary or continuum of identity throws policy argumentation to the outer darkness where there is wailing and gnashing of teeth. And that’s the point, especially if the policy agenda of a party is contradictory. Under those circumstances, instead of trying to defend policies, the most short-term effective rhetorical strategy is to go on the offensive, and deflect attention from one’s policies to the motives of the critics.

That’s exactly what the liberal and Democratic LBJ and his supporters did in regard to his Vietnam policies, as exemplified in their treatment of Morgenthau. Morgenthau put forward a sensible plan that was, it should be emphasized, grounded in anti-communism:

(1) recognition of the political and cultural predominance of China on the mainland of Asia as a fact of life; (2) liquidation of the peripheral military containment of China; (3) strengthening of the uncommitted nations of Asia by nonmilitary means; (4) assessment of Communist governments in Asia in terms not of Communist doctrine but of their relation to the interests and power of the United States.

In other words, the US should be prepared to ally itself with communist regimes, as long as they were hostile to China. This plan was similar to the policy the US justified as “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”–how we rationalized supporting unpopular authoritarian regimes with appalling human rights records rather than allow elections that might lead to socialist or communist (even if democratic) regimes–but with a more realistic assessment of the varieties of communism and the possible benefits of those alliances. As Morgenthau says, “In fact, the United States encounters today less hostility from Tito, who is a Communist, than from de Gaulle, who is not.”

Realism, as a political theory, claims to value putting the best interests of the nation above “moral” considerations, and strives to separate moral assessments of the “goodness” of allies from their potential utility to the US. We were, after all, closely allied with Israel, Sweden, and various other highly socialistic countries; why not add North Vietnam to that list, as long as it would be an ally?

That’s an argument worth considering. Morgenthau thought we should. Clearly, McNamara should have. He didn’t. We didn’t. Defenders of LBJ’s policies neither debated nor refuted Morgenthau’s argument. Instead, they shifted the stasis to Morgenthau’s motives and identity, pathologizing him, misrepresenting his arguments, and depoliticizing debate about Vietnam.

The Chicago Tribune published a short guest editorial (from National Review) June 12, 1965, and it’s worth quoting in full:

Prof. Hans Morgenthau’s hyperactive role as a protestor against our policy in Viet Nam is embarrassing many of his friends, and may even be embarrassing to himself, who is not used to the kind of self-exposure he is submitting to or to the company he finds himself keeping. (He was, it is reliably reported, distressed to see a photograph of himself standing next to Linus Paulding, and we cannot believe he looks forward to sharing the Madison Square Garden platform with the infantile leftist, Joan Baez.)

Morgenthau is a fine scholar and a first-rate dialectician. His Asiatic policies are heavily conditioned by his adamant Europe-firstism—much as the politics of Dean Acheson were. Then too, in 1960-61, Morgenthau went to Harvard as a visiting professor, expecting appointment to a new chair of government, McGeorge Bundy, then dean, nixed it—and may thereby have lit a fuse that is now exploding in anti-Johnson (and anti-Bundy) rallies around the country.

The Tribune editorial doesn’t misrepresent Morgenthau’s argument—it doesn’t even acknowledge he has one—nor does it characterize him as a dangerous person. Instead, it infantilizes and trivializes him by associating him with Linus Paulding and Joan Baez, embarrassment, infantilism, and leftism. It never argues that he’s infantile, trivial, and so on—the argument is made through association (such as characterizing his criticism of US policy regarding Vietnam as a “hyperactive role”).

There is a gesture of fairness–acknowledging that Morgenthau is a Professor and intelligent, but with a smear and dismissal. Morgenthau was Jewish, and one of many anti-semitic strategies for othering Jews was to refer to them as “Asiatic” (and therefore not really white)—Morgenthau’s ethnic background is irrelevant to whether he’s making a good argument. But, given the anti-semitism of the time, it would discredit him for some audience members. Similarly, whether he was a “Europe First,” or even whether that’s a bad thing to be, is irrelevant to whether his claims are logical, reasonable, and so on. The narrative about what happened at Harvard—whether true or not—also has nothing to do with the quality of Morgenthau’s argument.

But, dismissing an opposition argument on the grounds that the person has bad motives for making it (and it isn’t therefore a real argument) is persuasive to people who believe dissent constitutes out-group membership. We have a tendency to attribute good motives to the in-group and bad motives to the out-group for exactly the same behavior. Thus, the editorial says Morgenthau’s stance on Vietnam is purely the consequence of an academic rivalry. Why not assume the same of McGeorge Bundy’s stance? Why not assume that Bundy, if he did “nix” Morgenthau’s appointment, did so out of personal spite, and personal spite means he is taking the opposite position on the war from Morgenthau?

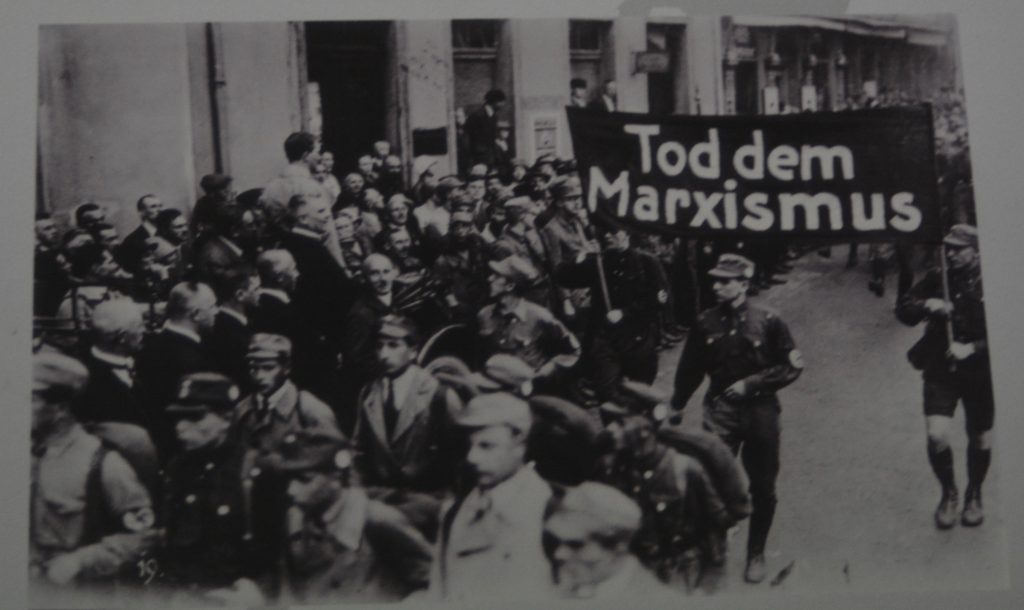

The slippage between Cold War rhetoric and policies meant that, as in the case of Vietnam, the US was in the paradoxical position of claiming to promote democracy, freedom, and independence while helping major powers (like France) hold on to colonies, supporting anti-democratic (even openly fascist) governments, suppressing elections, and silencing free speech even in the US:

The cold war was an all-encompassing rhetorical reality that developed out of Soviet-American disputes but eventually transcended them to reach to American perceptions of Asia and to American actions against domestic dissidents. This ideological rhetoric became so embedded in American consciousness that it eventually limited the political choice leaders could make, created grossly distorted views of adversaries, and finally led to the witch-hunts of McCarthyism. (Hinds and Windt xix)

Given the way the Cold War rhetoric paired terms worked, to criticize an “ally” or any US policy could be framed as endorsing the USSR. This despite the fact that we were often not promoting democracy, that not all forms of communism were imposed by a Soviet-led minority on an unwilling populace, and that silence of dissent was one of the main criticisms of the USSR. Thus, in service of battling an enemy one of whose crimes was silencing dissent, we silenced dissent.