I recently found my notes and files from when I was writing my dissertation. I’ll start with saying that I’ve had a respectable publishing career, but hooyah, that dissertation was a hot steaming mess. So was my process of writing it. So, if you’re trying to write a dissertation, and you’re in the midst of a chaotic writing process and you think that what you’re writing is awful, it can’t be worse than either my process or product. You’ll be fine.

There’s a longer version of this, but here I’ll list a few ways that things went wrong. First, I was trying to use a technology that lots of people used (a notecard system), but it really didn’t work for me. I didn’t know that, and I couldn’t have known it till I tried it. It got me too caught up in details, and I’m an inductive thinker (and writer), and it worsened all the flaws of inductive writing (assuming that if you give enough details people will infer your argument).

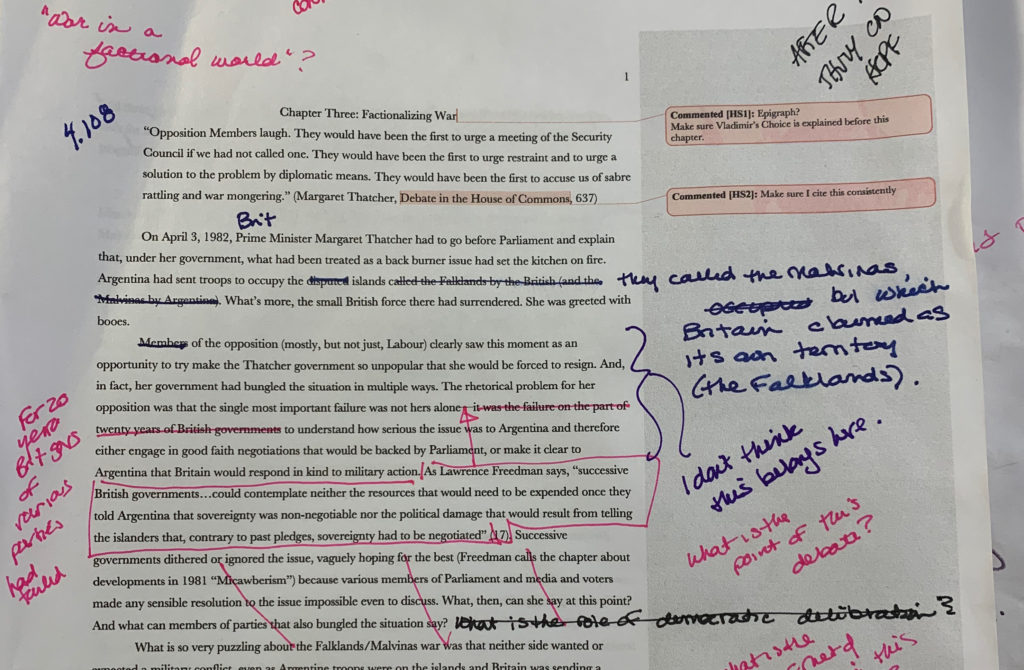

There are lots of technologies that people now use—zotero, commenting on pdf—and they work for some people and not for others. If one that other people are using doesn’t work for you, then committing to it with more will won’t make it work. It doesn’t mean you’re a failure; it means there’s a bad match between that technology and you, and the technology needs to go.

Second, I was working with faculty who were not in the conversation I was trying to enter. That was simply a function of my topic and department. My committee was really good, but they couldn’t tell me what to read or what conferences to attend. Make sure someone on your committee knows the conversation, or change the conversation.

Third, I was modelling my argument on books I admired that were written by advanced scholars. Your dissertation, in terms of scope and structure, should be modelled on books written by junior scholars or other dissertations in your department.

Fourth, people writing their dissertations should be prohibited from making any major decisions regarding things like marriage.

Fifth, I was in a highly competitive department in which something like a writing group would probably not have been helpful, but I wish I had found one. It’s hard, though, since people outside your field will often give advice that isn’t appropriate for yours.

How things went right.

First through fifth: my dissertation director was a smart, insightful, and kind person. He was a student of Thomas Kuhn’s, and so stepped back and saw processes. When you’re writing a dissertation, there are moments you are completely paralyzed. It’s because we’ve often gotten through undergrad and coursework without thinking about structure very much. So, you go from thinking about how to structure a 20-page paper (or not, you just make it a list) to how to structure something that is 200 pages. You have to decide what’s background, where to explain that background, how to position yourself in regard to other scholarship, how much of that scholarship to discuss, where to start…so many things that just don’t come up in a seminar paper.

My director, Arthur Quinn, taught a course about 18th century rhetoric that was entirely histories of the 18th century that happened to emphasize rhetoric, and we spend the semester talking about their methods, structures, assumptions, rhetoric. It was one of four classes I had in that program that were historiography (maybe five), but I didn’t know that at the time. What I did know is that he was asking us to step up a ladder, from just thinking about our data, or our argument, to the various ways we might make that argument. That course influenced every single grad course I taught.

At one point, completely paralyzed in my writing, I was in a grad student office, rearranging the Gumby-like figures my office-mate had into a baseball game. His office was next door, and he stopped, looked in, and then went to his office. A while later, he came into my office and said, “Here’s what you’re arguing.” He gave me an outline for my dissertation. I started writing again.

My dissertation did not end up with that outline. But his giving me that direction got me writing. He was generally a hands-off director, but he knew the moment he had to step in.

Now that I’ve seen a lot of grad students, and a lot of directors, I appreciate him so much. A lot of scholars rely on panic to motivate themselves, and so they sincerely believe they are helping their students when they deliberately work their students into a panic. Many rely on shaming themselves in order to write, and so they think that shaming students is helpful. Some forget how hard it is to write a dissertation, and so they dismiss or minimize the concerns of their students. Some believe that they benefitted from how isolating writing a dissertation is, and so they believe that refusing to give directive advice is helping their students. Some have writing processes in which you have to have the entire argument determined before you start, and so they insist their students do. Some drift around in data and so encourage their students to do so. All of these processes work for someone—that’s why people adopt them—but none of them work for all students, and none of them work for any one student all the time.

And that is what Art Quinn taught me.