Discussions of American politics typically describe either a binary or continuum of left v. right, a model that is both false and damaging.

First, the false part. The model comes from the French Assembly, when one issue was at stake—what should happen with the monarchy, and so it was possible to describe the various people involved as on a continuum. The positions of participants ranged from wanting a strong monarchy, to constitutional monarchy, to no monarchy or aristocracy at all. They sat in a way that put those in favor of retaining a monarchy on the right, and those in favor of abolishing it on the left. So, it made sense in that moment.

It makes less sense when we’re talking about a variety of policy options, as we are when we’re talking about current politics. It seems to makes sense if the topic is voting patterns for Federal elections, in which case it’s pretty useful to say that there are people who

• will only vote socialist or Green;

• are varying degrees of likely to vote socialist/Green v. Dem;

• will only vote Dem;

• are varying degrees of likely to vote Dem or vote GOP;

• will only vote GOP;

• are varying degrees of likely to vote Libertarian v. GOP;

• will only vote Libertarian.

Notice, though, that it isn’t a binary, and that it’s more of a spectrum of colors going from green through turquoise, blue, lavender, red, orange, yellow. Notice also that it doesn’t make sense to talk about the points at either end as more “extreme.” If you pay attention to actual policy agenda and voting patterns, then it’s clear that Libertarians aren’t more extreme versions of Republicans—they have a different policy agenda–, and it’s the same with Green Party and Democrats.

It isn’t an accurate description of where people stand on particular issues, even polarizing issues like abortion, gun control, civil rights, or immigration. [1] When people are talking about policies, there can be coalitions for particular kinds of changes that draw from all over that spectrum (such as regarding prison reform, decriminalizing drug use, bail reform).

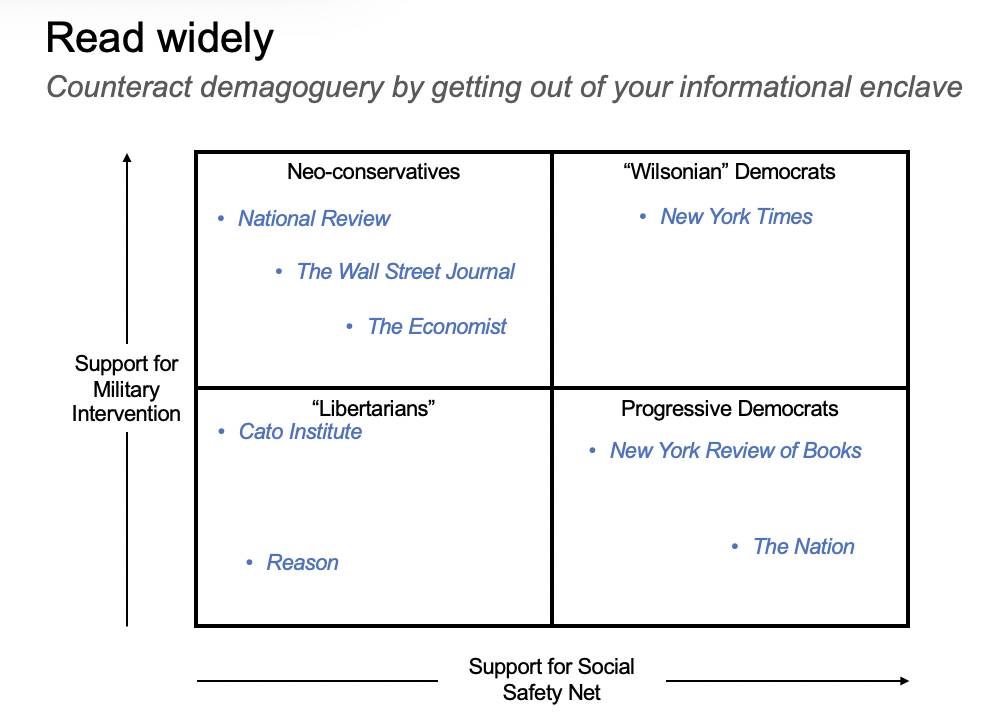

There are two other axes that are important for thinking about American politics. One is domestic v. foreign policy issues, mapped above. There are people who vote consistently Dem in regard to domestic policy, but are supportive of military intervention (generally for humanitarian reasons). There are people who vote GOP consistently in regard to domestic policy, but are opposed to military intervention (essentially isolationist).[2]

The other important axis is degree of commitment to one’s place on the spectrum—that is, the extent to which one believes that other positions are legitimate and should exist. There’s a sense in which this is one’s commitment to the process of democratic deliberation. Republicans will sometimes argue that we aren’t a democracy, but a republic. I think that’s a tough argument to make past the Jacksonian opening of citizenship rights, but it sort of doesn’t matter. We can call our sort of government a democratic republic, representative democracy, liberal democracy (not in the American sense of “liberal”). Regardless of which terms one uses, the point is that our country was founded on the notion that disagreement is beneficial, that a community thrives when there are multiple perspectives, that determining the best policy is challenging.

There are people all over the political spectrum who reject that premise, who believe that their (and only their) position is entitled to power and that all other positions should be silenced, or at least marginalized.[3] Those people should be described as extremists. A Libertarian or socialist who is a passionate supporter of their party is not necessarily any more of an extremist than someone who only votes moderate Democrat. I think we should reserve the word “extremist” for someone who wants the political sphere purified of everyone other than them.

Very few people (maybe zero?) care about every policy issue, but most of us have one or two about which we care passionately. When we talk about those one or two policy issues, commitment to parties weaken, since it’s unlikely that a party is going to promote the one policy we want exactly as we want it. For instance, global warming might be the biggest issue for both of you and me, but that doesn’t mean we’re in perfect agreement as to what we should do. I might think the Kyoto Accords are great, too weak, too strong, the wrong route, and you might take one of the other positions. Or, let’s say that we both strongly believe in strict limits on immigration—we’re extremely likely to disagree about the details (especially when it comes to enforcement). To get the votes, a political party is going to have to form a coalition of people who disagree—that’s easier if we don’t know we disagree. And that is easier if we keep the discussion to vague assertions of policy goals (the vaguer the better)[4]. It’s even easier if we don’t run for our policy agenda at all, but run against Them. And that’s what Outrage Media is all about—it’s about getting clicks, links, shares, views, and commitment by ginning up outrage about how awful They are (for more on this, I think The Outrage Industry is really useful, but so is Network Propaganda).

Just to be clear, sometimes there is a group that is awful. What the Outrage Media does, though, is group all of our opponents into that one category. For instance, a lot of media talks about how awful “conservatives” are, putting Libertarians, fundagelicals, neo-conservatives, Trump supporters, and GOP loyalists all into one group. Those are fairly different groups. For instance, Libertarians and the GOP both claim to value neoliberalism, but Libertarians have a stronger commitment to it (the GOP is very supportive of government intervention in the market despite claims otherwise). So, some people try to claim that Libertarians are just a more extreme version of Republicans.

But the Strict Father Morality of the GOP is more important to its policy agenda than neoliberalism (as is shown by how GOP political figures behave when the two values are in conflict, such as in the case of bailouts, corporate subsidies, military intervention, laws regarding drug use). And it’s in that regard—the one more consistent in GOP policy commitments–that Libertarians are not more extreme than the GOP.

In other words, thinking that the binary/continuum accurately represents political ideology (at least if we think that political ideology is representative of policy agenda) is inaccurate. It’s damaging because it’s nutpicking—we allow the Outrage Media to persuade us that the outliers of the outgroup(s) represent everyone who disagrees with us. We therefore not only fail to see possible shared policy options, but demonize compromise itself (it’s trucking with the devil). We aren’t even open to thinking about what might be wrong with our policy agenda because we dismiss everyone who disagrees with us. We are on the road to mutual extermination.

[1] There are people who consistently vote Democratic who are opposed to legal abortion and gay rights, for instance. Many self-identifying Republicans support far more control (and they support it far more) than the NRA or GOP would have you believe. Everyone is in favor of immigration, and very few people are in favor of unlimited immigration—the question is how much, and what to do about illegal immigration.

[2] You may have noticed I’m up to four axes (or at least three). In other words, we should either stop trying to create one map for everyone (and think and talk in terms of policies rather than identities) or else just try to map where people stand on specific issues. I think we’d discover a lot of common ground.

[3] There are, for instance, people who believe that we should purify the Democratic Party of all but the centrists—that’s just as much a politics of purity as people who believe the party should become purely progressive. People who argued for the political extermination of anyone who advocated integration claimed to have the moderate position, and may have sincerely believed they did. I intermittently run across supporters of the GOP who want the Democratic Party political exterminated, and they seem to see themselves, quite sincerely, as thereby eliminating “extremism”—but they’re advocating an extreme position. Their extreme commitment to their position is extremist.

[4] There’s some research that says that people likely to vote Dem are more likely to be policy wonks, and really want to hear and debate the details of policy. Thus, people trying to mobilize Democrats are in a double-bind, of needing enough policy talk to get the votes of the wonks like me, but not so much as to alienate potential voters.

A lot of people believe that the Nazis were leftists. These are people who believe that the complicated and vexed world of thoughts about politics can be divided into an us (right wing/conservative) and everyone else, whom they think of as leftists. And that our current categories of politics go back through eternity.

A lot of people believe that the Nazis were leftists. These are people who believe that the complicated and vexed world of thoughts about politics can be divided into an us (right wing/conservative) and everyone else, whom they think of as leftists. And that our current categories of politics go back through eternity.