Since I’m a policy geek, it’s long interested me that a tremendous number of people don’t care about policy at all. An awful lot of people’s political affiliations seem to me to be motivated by two things: 1) a sense that being affiliated with this party means you are this sort of person (an ethos they like); and 2) the argument that you should be angry because They are keeping you from getting the things to which you’re entitled, so you should vote against them.

Some day, I’ll write about that first motivation. It’s really weird, and it’s really just my crank theory, based on my trying to talk to people, but I think this mobilizing ideology has been used at least as far back as the eighties. It seems to me to work better for the GOP than other parties, but I have no data to support that. It’s more than just identification, and it isn’t always charismatic leadership. Here’s my crank theory. The GOP doesn’t have a coherent policy agenda, but it has a coherent ethos. It presents itself as the party of people (mostly men) who have no doubts about their position, can see clearly what the right course of action is, will refuse to compromise, and know (and will act on the knowledge) that, in every situation, it is a binary of right or wrong.

And, paradoxically, right or wrong isn’t whether what you’re doing in this moment is right or wrong, but whether you’re endorsing the group that believes right or wrong is binary. If what you’re doing is helping the group that says right or wrong is binary, then your actions are right even if they’re exactly what you condemn the out-group for doing. This is Machiavellianism, in which the ends justify the means, and the ends are just in-group successes. I’ve written about the Machiavellianism part (which is far from particular to pro-GOP rhetors), but not about the extent to which people who support the GOP do so because they see it as the party of the strong and decisive man. But, that isn’t this post.

This post is about the second puzzle for me—that pro-GOP rhetoric (Fox and Limbaugh. are good examples of this) is a rhetoric of grievance, of being wounded, including being victimized by people saying that they are racist (while projecting that living in perpetual grievance onto others, so they can still seem to be strong men, what Paul Johnson calls “masculine victimhood”).

People advocating racist policies resent being called racist. It isn’t just that they dislike it, or that they disagree, but they resent it.

They are filled with and fueled by resentment. They sincerely believe that there is an “elite” of professors and out-of-touch artists who are keeping them down. They resent the power that this “liberal elite” uses against them. Were it not for this “liberal elite” they would… and here things get vague. Deliberately so. Limbaugh et al. never say what, exactly, would happen were this “liberal elite” to lose power because that would involve creating a coherent narrative of the “ill” created by the “liberal elite.” Limbaugh et al. can’t do that, because there isn’t one. And that’s how resentment works; it isn’t an affirming passion that enables progress; it’s entirely negative, about taking power and good things away from an out-group.

I spent a lot of time deep in the arguments that people made for slavery, and it was bizarre to me the extent to which people whose financial situation was grounded in the buying and selling of other humans felt victimized. They were victimized by having to abuse other humans in order to maintain their financial and political situation and by having to hear people point out that they were engaged in abuse. They resented the criticism. Pro-slavery rhetoric was a rhetoric grounded in slavers’ resentment that they were being criticized for being slavers.

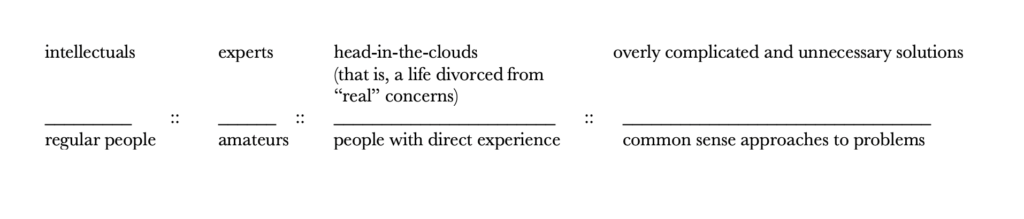

But when I looked at scholarship and theorizing of resentment, I kept ending back on Nietzsche’s notion of ressentiment, and it was deeply unsatisfying because his narrative seems to me unhelpfully elitist. And yet it’s common—the notion that resentment is the feeling that inferior people feel about people they secretly believe are better. I don’t think that’s a useful way to think about resentment for several reasons. One of them is that this way of identifying resentment means we’re deep in the world of motives and secret feelings (as well as seeming to accept that some people are better than others), and I think those criteria get us into areas that make self-diagnosis impossible. I’m not saying it’s wrong—I do think the way that resentful rhetoric works is a kind of mean girl strategy. I tell you the mean thing that Heather said about you (which she may or may not have said or even thought) in order to get you to ally with me against her. I tell you that Heather looks down on you, which triggers your defensively looking down on her for looking down on you. That’s the basic plot of a large amount of Limbaugh et al.’s broadcasts. That’s the whole strategy of “libruls look down on you”—it’s oriented toward triggering a kind of polarizing resentment that strengthens in-group commitment.

But an awful lot of political activism begins by pointing out that some group looks down on us, and they think we’re going to continue to put up with their shabby treatment, but we aren’t. So, I spent a lot of time trying to figure out if there is a difference in the rhetoric between the “libruls look down on you” and “this group in power is just throwing us crumbs to keep us shut up.” And I think it’s ultimately the point mentioned above—what are we supposed to do with our resentment?

The Limbaugh et al. resentment is purely reactionary and negative—taking power away from “libruls” is winning. As long as they are hurt, we win—the gain is their loss, and that’s the only gain there needs to be. Thus, you can have what is often called “Vladimir’s Choice.” “Vladimir’s Choice” is a term from a Russian tale. God comes to Vladimir and says, “I will give you anything you want, but whatever I give to you, I will give twice that to Ivan.” Vladimir thinks about it for a while, and then says, “Take one of my eyes.” Vladimir so resents Ivan that he is happy to be hurt, as long as Ivan is hurt more.[1]

If we feel that They are denying us something to which we’re entitled, we’ll settle for it being taken away from them. If we think we’re denied the vote, or good healthcare, or a decent wage, then we’ll feel that it’s a win if we deny Them the vote, good healthcare, a decent wage. That’s resentment.

But the other kind of entitlement is (or at least can be) affirming—it’s about gaining certain rights and powers. If we’re being denied the vote, then we don’t want them denied the vote; we want the rights and powers they have. They can keep their healthcare and decent wages, as long as we get those things too.

And here we come back to the point I keep making—how vague the pro-GOP rhetoric is about policies. There are a lot of statements of rigid commitment to slogans (“safe borders,” “pro-life,” “tough on crime”) but there aren’t clear statements of what policies will get us there, let alone policy argumentation to show that those policies will feasibly solve the clear problems. Affirmative entitlement arguments can (and do) make those policy arguments—“defund the police” (a slogan) was backed by detailed policy discussions and arguments. “Build the wall” wasn’t. I’m not saying that I agree with “defund the police”—in fact, there were a lot of very different policies that people meant by that same slogan. My point is that I think there is a useful distinction between affirmative entitlement arguments and resentment, and that resentment is purely reactionary and negative.

I want to end this post by pointing to two different yard signs. The one on the left lists six beliefs, with only one framed as a negative (“no human is illegal”). On the whole, it affirms positive statements. The one on the right has eight claims. It’s mildly incoherent: who doesn’t believe in legal immigration? And if violence is not the answer, isn’t that saying that the police shouldn’t be violent? Isn’t “police” a category of people? More important, notice how negative it is—five of the eight claims are explicitly negative, about what should not happen and how people should not think. It’s about how wrong They are.

[1] Some studies show that Vladimir’s Choice increases with the perception of intergroup competition and what’s called “social dominance orientation” (essentially, the notion that groups should remain in a stable hierarchy, with “better” groups dominating the “lower” groups), an orientation that correlates to self-identifying as conservative.