This paper came out of my being puzzled by a paradox I kept running across in the various deliberative train wrecks I study—the intermittent moralism of Machiavellian approaches to public policy disagreements. “Machiavellianism,” only orthogonally related to what Machiavelli actually said, claims to treat means as morally neutral, often in service of some version of power politics or neo-Social Darwinism. But this amoralizing of means is both rhetorical and flickering—American intervention in Vietnam, for instance, was advocated on the grounds of moral necessity and amoral power politics, sometimes in the same document.

What I’ll pursue in this paper are some of the somewhat paradoxical rhetorical consequences of this disingenuous framing of means as amoral.

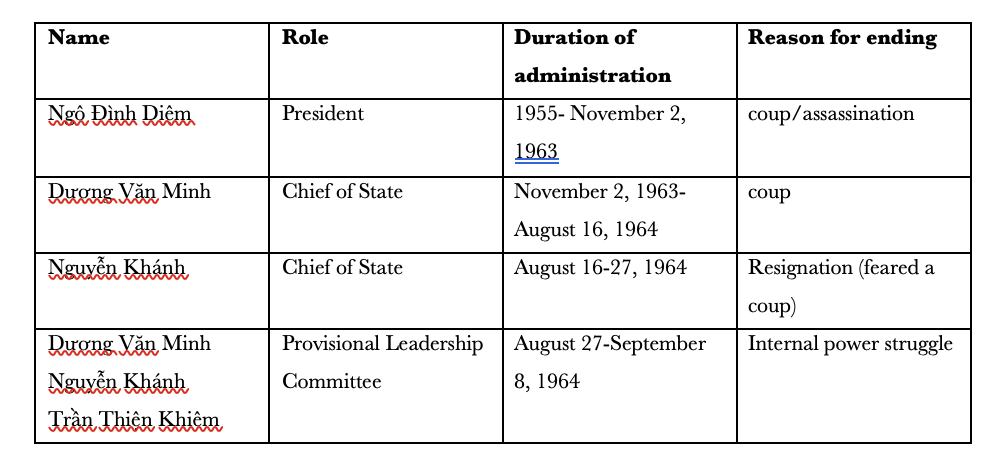

I’ll focus on US decision-making regarding Vietnam in August of 1964. August of 1964 is one of several moments of escalation, with attention generally on LBJ’s decision to lie in order to get the Tonkin Gulf Resolution passed on August 7. But I’m more interested in the chaotic debacle that was General Nguyễn Khánh’s not-quite month as Chief of State. I’ll start by discussing the objectives (ends) at the time, the necessary conditions for success, the actual conditions (as described by US decision-makers), the means they chose, and finish with how Machiavellianism played into it.

Ends In an August 10 “situation report,” Maxwell Taylor, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and recently appointed US Ambassador to the Republic of Vietnam said that the “Communist strategy” was not

“To attempt to defeat the superior Republic of Vietnam military forces in the field or to seize and conquer territory by military means. Instead, it is their announced intention to harass, erode and terrorize the population into a state of such demoralization that a political settlement favorable to the Communists will ensue.” (#306, 657).

Robert McNamara would later identify policies in 1964 as oriented toward “the objective of destroying Hanoi’s will to fight and its ability to continue to supply the Vietcong” (In Retrospect 152). In an important –strategy setting—document in August of 1964, McGeorge Bundy said we must “make it clear both to the Communists and to South Vietnam that military pressure will continue until we have achieved our objectives [….] leaving no doubts in South Vietnam of our resolve” (#313, 675). By persuading “the Communists” that the US would not give up Vietnam, it was hoped that “the Communists” could be persuaded that a divided Vietnam—much like Korea—was the best deal they could get, and therefore take it.

Necessary Conditions To achieve those ends—a Hanoi willing to agree to a divided Vietnam—certain conditions had to exist. RVN had to be an effective and largely victorious force, capable of exterminating the insurgency without alienating the populace. The “pacification” program was crucial for achieving several of the conditions—denying communist support for the Viet Cong, maintaining the morale of the populace, achieving military victories—and it depended on “clearing” certain areas of Viet Cong agents and supporters. South Vietnam had to have a competent, trusted, and stable government. The South Vietnamese people needed to support that government, and support the war (which could only happen were the first condition met). The US had to signal willingness to throw limitless resources at the conflict. These various conditions tended to be characterized as issues of “morale” (or its opposite—“defeatism”) in official documents, documents that admitted none of those conditions were present.

Actual Conditions In that August 10 “situation report,” Taylor acknowledged that the South Vietnamese military was weak, while trying to put a positive spin on it: “In the view of US advisors, more than 90 percent of the battalions of the army are at least marginally effective.” (#306; 661). The pacification program was “proving to be a most difficult one primarily because of the inefficiency of the ministries, their ineptitude in planning and their general lack of spirit of team play” (Taylor 659). In a memo ten days later, Taylor said, “that the present in-country pacification plan is not enough in itself to maintain national morale or to offer reasonable hope of eventual success.” But the worst was the government. The US had endorsed the November 1963 coup on the grounds that Diem was corrupt, incompetent, and tremendously unpopular. He had collaborated with the Japanese (unlike Ho Chi Minh, who fought them), was brutally persecuting Buddhists, and may have been considering a peace treaty with Ho. The hope was that replacing Diem would increase Vietnamese commitment to the war by putting in place a more popular, competent, and bellicose government. It didn’t work (as can be seen in the chart at the top.

Taylor said

The most important and most intractable internal problem of South Vietnam in meeting the Viet Cong threat is the political structure at the national level. The best thing that can be said about the present Khanh government is that it has lasted six months and has about a 50-50 chance of lasting out the year [….] It is an ineffective government beset by inexperienced ministers who are also jealous and suspicious of each other [….] However, there is no one in sight who could do better than Khanh in the face of the many difficulties which would face any head of government [….] The attitude of the people toward the Khanh government, mostly confused and apathetic since its inception, is only slightly more favorable than a few months ago. Despite considerable efforts, Khanh has not succeeded in building any substantial body of popular support. (657-658).

August 13, 1964, McGeorge Bundy presented a plan called “Next Steps in Southeast Asia, “a highly important document” (Logevall 217). McNamara would later say that “the memo and its derivatives became the focus of our attention and acrimonious debate for the next five months” (In Retrospect 151). The first sentence of the section, “Essential Elements in the Situation” is “South Vietnam is not going well” (#313, 674).

Taylor responded to Bundy’s “Next Courses of Action” (which he endorsed that one assumption behind Bundy’s proposal (which he believed to be correct) is:

The first and most important objective is to gain time for the Khanh Government to develop a certain stability and to give some firm evidence of viability [….] A second objective in this period is the maintenance of morale in South Viet Nam, particularly within the Khanh Government [….] he must stabilize his government and make some progress in cleaning up his own operational backyard. (690)

The Course of Action that Bundy’s memo advocates, and Taylor endorses, “relies heavily upon the durability of the Khanh Government. It assumes that there is little danger of its collapse without notice or of its replacement by a weaker or more unreliable successor” (692). Ten days later, worried about a coup, Khanh himself would resign and skedaddle to Dalat. He had to be coerced to come back and form a triumvirate. There were no illusions about the instability and unpopularity of the government, and yet the US was pursuing a plan that, as was repeatedly insisted, depended upon a stable and popular government, which US officials knew they didn’t have. They did, however, have one that wouldn’t negotiate with Hanoi.

The Means

One of the “means” necessary for success was preventing peace talks: “We must continue to oppose any Vietnam conference” (#313). After listing the various means the US should take, Bundy says,

These actions are not in themselves a truly coherent program of strong enough pressure either to bring Hanoi around or to sustain a pressure posture into some kind of discussion. Hence, we should continue absolutely opposed to any conference. (#313; 678).

That this was the means was not publicly admitted. But the conservative and “realist” political scientist Hans Morgenthau had figured that out, snarkily noting in an article in New Leader in June of 1964:

Our main immediate problem is apparently not to win the war against the Viet Cong but to prevent the ascendancy of an anti-war government in Saigon. What we are saying and doing must, then, have as its main purpose to prevent the collapse of the morale of General Nguyen Khanh’s government and of its military forces (44).

Thus, American Vietnam policy in 1964 was to prevent negotiations with Hanoi until the morale, bellicosity, and military effectiveness of the South Vietnamese was such that Hanoi (and China) would believe that a divided nation was the best they could possibly get: “We need to apply “a combination of military pressure and some form of communication under which Hanoi (and Peiping) eventually accept the idea of getting out” (#313). The “Next Course” also advocated dropping leaflets, increased training of RVN forces, mining of the Haiphong harbor, “tit-for-tat” actions, only acknowledging successful military actions. Taylor said, “The US Mission has recognized in its information and psychological programs the need to present the Khanh government in its most favorable light at home and abroad, particularly in the United States” (# 306 660).

What I hope is striking to you is that the means were profoundly rhetorical; they were about persuasion—persuading the North Vietnamese they couldn’t win, and the South Vietnamese that they could. South Vietnamese needed to be persuaded to support the war, and both the South Vietnamese and Americans needed to be persuaded to have faith in the Khanh government—its stability, competence, and resolve. But even the American officials themselves weren’t persuaded of any of those things. So, the Machiavellianism came to be the approach to public deliberations—critics of American policy in Vietnam had to be smeared, discredited, and deflected. Preventing reasonable discussion of Vietnam policy itself became a means necessary for the ends.

Machiavellianism

I mentioned earlier that McNamara said the US objective was destroying Hanoi’s will to fight and ability to support the Vietcong. He said, “Neither then nor later did the chiefs fully assess the probability of achieving these objectives, how long it might take, or what it would cost in lives lost, resources expended, and risks incurred” (152).

The amoralizing of means didn’t mean they were actually neutral—there is nothing morally neutral about napalm—it just meant that people could deflect or even demonize public discourse that criticized the ends or means. The ends (and therefore the morality of the means) are themselves outside the realm of argument—they’re simultaneously obscured and circular (since the postulated morality of the ends or intentions justifies being dishonest about what the ends or intentions actually are). We can’t argue reasonably about the ends—because they’re postulated as moral—and we can’t argue at all about the morality of the means. Thus, amoralizing policies (the means) necessarily results in the demoralizing and depoliticizing of public discourse. The point I’m makingis that US officials (like many others) were Machiavellian not just in terms of their use of napalm, but their approach to public discourse. And my crank theory is that one necessarily leads to the other.