A lot of people make the point that there was a kind of racism—called “old” racism—that was openly biological/genetic, and openly hostile. Then, at a certain point, racist discourse shifted to become more genteel. That distinction between old and new racism isn’t entirely accurate, and the way it’s inaccurate is important. There have always been “genteel” racisms—what might be called “racism with a smile” or “some of my closest friends are…” racism. And those “nice” (that is, socially acceptable) racisms enable the kinds that openly advocate violence, expulsion, and extermination.

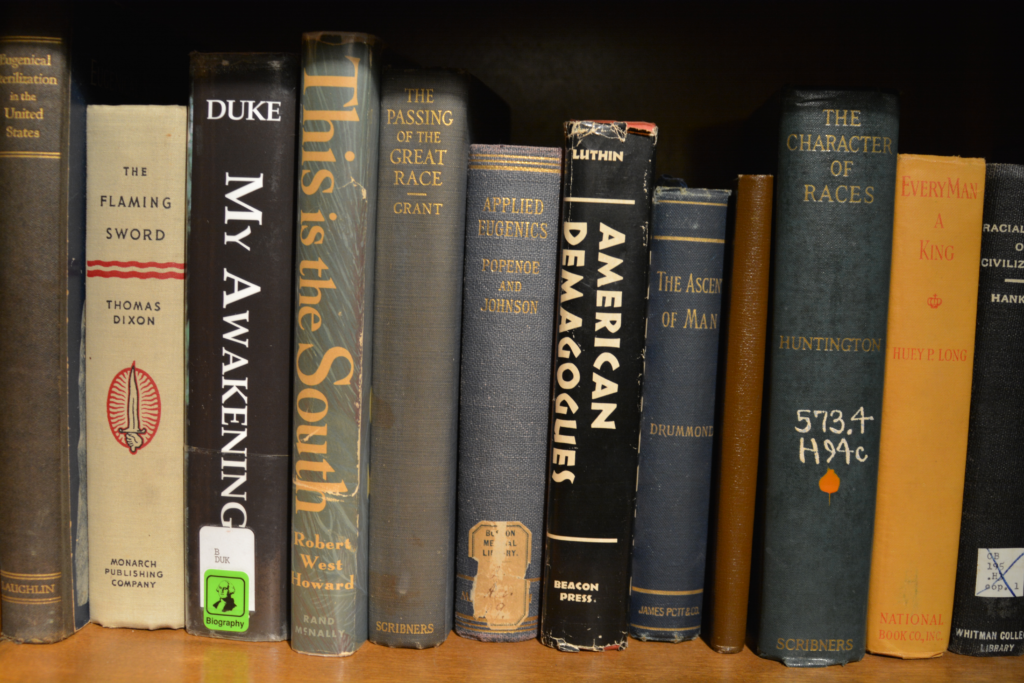

In this post, I want to talk about one of them—one that was tremendously popular in the twentieth century. This view accepted that there were “races,” that they were essentially (even genetically) different, that these differences manifest themselves in external characteristics (looks, behavior, cultural practices), but that all of these differences add to the richness of human life. This kind of racism celebrated the essential differences of human races. (Sort of. I’ll get to that.) People advocating this kind of racism often explicitly set themselves off from a similarly biological racism (they weren’t racist) on the grounds that they weren’t that bad.

Take, for instance, Dorothy Sayers, the mystery novelist. In Whose Body (1923), the villain kills a perfectly nice Jew out of spite with a non-trivial amount of antisemitism. The hero expresses no antisemitism, not even when his friend indicates a desire to marry into a Jewish family, and the narrator has nothing negative to say about the victim or his family. In fact, everything we hear about the victim and his family appears positive. He is very good at playing the stock market and therefore wealthy, but not showy in this wealth (for instance, because he doesn’t have a chauffeur, he travels alone to the meeting the murderer has set up). He dotes on his wife and daughter, and is a good family man. He is kind to people.

This all appears positive—he’s smart, successful, modest, and a family man. This characterization is, however, simply the “positive” side of the same coin of rabidly antisemitic rhetoric. For those groups, Jews are: parasitic capitalist, money-grubbing, cheap, tribal (“clannish” is the word sometimes used), and kind becomes “pacifist” or “cowardly.”

Antisemitic rhetoric in groups like the Nazis stuck close to the producer/parasite dichotomy that runs back through readings of Paul’s prohibition about usury. Chip Berlet and Matthew Lyons have a useful description of how that dichotomy plays into toxic populism. The short version is that toxic populism presents some group as producers, and the other as parasites, or, in Paul Ryan’s more recent rhetoric, “makers” and “takers.” The in-group is always makers. For many populists, people who make money off of money—financiers, people who play the stock market—haven’t really created wealth (such as through owning land). They’re parasites.

Nazis were populists (authoritarians almost always are, even though their policies actually screw over most of the populace, and especially the middle and lower classes). The notion that Jews were always financiers and stock market geniuses (and bankers) was one of the most important aspects of Nazi antisemitic propaganda. It’s a theme in Mein Kampf, fercryinoutloud. Real money, so this argument goes, comes from agriculture, or perhaps small manufacturing. Being good at the stock market, for Nazis, is a smear.

Similarly, the negative stereotype of Jews was that they can never really be patriots, because they always favor their family rather than their country (for Hitler, an “Aryan” putting his family first is putting the country first). And the stereotype of Jews as cheap was another piece of antisemitic rhetoric. In other words, Sayers, even if her portrayal of a Jew appeared sympathetic (i.e., she was trying to be “nice”), reinforced exactly the stereotypes that resulted in the Holocaust: Jews are good at finance (capitalist parasites), modest (miserly), family lovers (clannish), non-violent (pacifists and cowards). It was racism with a smile.

She was far from alone. After Wyndham Lewis’ enthusiastic paean to Hitler (1931) didn’t go over as well as he’d expected, and his insistence that Hitler was “a man of peace” showed him to have been very wrong, he tried to get back in the good graces of the public with his Jews: Are They Human? (1939). His answer is that they have their own virtues—they’re very loyal to one another and family-loving (clannish), careful with money (greedy and miserly), and so on. Like Sayers, he put it in positive terms, but it was still endorsing the notion that Jews have an essential set of characteristics.

Lewis took Hitler’s claims of wanting world peace at face value, but it’s interesting that he didn’t take Nazi antisemitism at face value. I think it’s because he didn’t really object to it all that much. Lewis and the Nazis didn’t disagree as to the basic character of Jews; they just disagreed as to what should be done about it. So, for Lewis, Hitler’s antisemitism wasn’t especially notable—it was something he could dismiss as a little bit of an overreaction.

What has been a little surprising to me in working on demagoguery, especially when it leads to extreme policies about the cultural out-group, is the number of people who consider themselves “moderate” who endorse the basic narrative behind the demagoguery about the out-group. They just don’t think it should be taken too far.

Germans who agreed that there should be a quota for Jewish doctors, Americans who agreed that integrated schools were just a little too much, Brits who wouldn’t want their daughter to marry one—they could all see themselves as “not racist” (or, at least, not unreasonable in their attitudes toward Those People) because there was some other group less nuanced, less reasonable in their hostility. And, when push came to shove, they might raise an eyebrow at the people who did go “too far,” or perhaps mutter some criticism, but that’s about it. They were often allies, and rarely enemies, of the people who went “too far.”

Thus, that we now have people who say “I’m not racist, but…” isn’t a sign that there is a new kind of racism. It’s an old form, and a very damaging one.