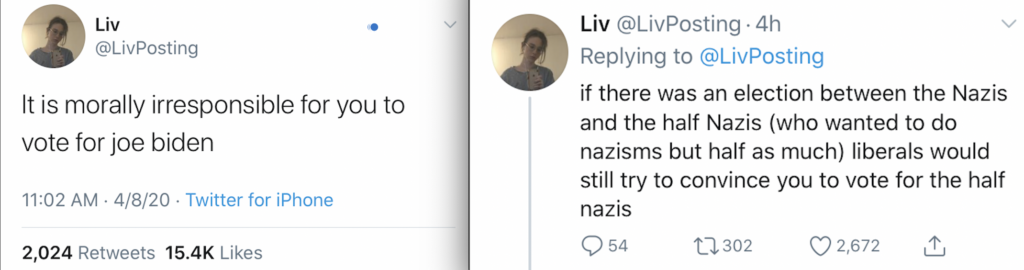

The above are two very popular tweets (as you can see from the likes), and they rely on a way of thinking about political choices that is often popular. The argument is that you shouldn’t vote for this person because s/he is still in a category of evil people.

You see it all over the political spectrum (we need to stop talking about either a binary or single-line continuum of political positions—it’s false and damaging, and it fuels demagoguery). In 2016, there were informational enclaves that said that people should vote against HRC because she was a socialist, fascist, neoliberal, and therefore no different from Stalin, Hitler, Thatcher.

It’s a way of arguing that eats its own premises, and yet it’s so often persuasive. For instance, the argument that you shouldn’t vote for Biden because he’s half the nazi that Trump is has the major premise that you should never choose the thing that is twice as good.

Of course you should choose the thing that is twice as good. You should buy the car that is twice as good, rent the apartment that is twice as good, take the job that is twice as good. When we’re deciding about a car, apartment, or job, we can do that math, but, when it comes to politics, suddenly people can’t see that half a fascist is twice as good as a full fascist, let alone whether Biden is half a fascist.

So, why do people who can take an imperfect apartment that is twice as good as their other option, when it comes to politics, reject taking an option that is twice as good as the other?

There are a lot of reasons. Here, I want to mention two. First, politics is tied up with identity in a way that getting an apartment usually isn’t (although, people I’ve known for whom their apartment is closely attached to their identity have the same bad math—an apartment twice as good as the other is just as bad as the other); second, people who reason deductively often have false narratives about the past, or don’t care about what has happened. A politics of purity is often connected to a belief in belief.

The first move in that argument is to treat everyone who disagrees with us as in the Other category. There are good arguments that Trump is fairly high on the fascism scale (although with some important caveats, particularly about individualism), but Biden is not a fascist. He’s a third-way neoliberal. But, really, when people are making this kind of argument—HRC is basically Stalin, Sanders is Castro, HRC is Trump—they aren’t putting the argument forward as some kind of invitation to a nuanced discussion about political ideologies. It’s a hyperbolic appeal to purity politics.

Like all hyperbole, the main function of the claim is that it is a performance of in-group fanatical commitment, a demonstration of loyalty on the part of the speaker. The point is to demonstrate that they think in terms of us or them, and they are purely opposed to them.

That seems like a responsible political posture because, in cultures of demagoguery, there are a lot of people (who are bad at math) who decide that being purely committed to the in-group is the right course of action, regardless of whether that has ever worked in the past. They believe that we can succeed if we purely commit to a pure commitment to a pure in-group set of pure policies. That way of thinking about politics—the way to win in politics is to refuse to compromise—is all over the political spectrum.

And, I just want to emphasize: the math is bad. A half-nazi is actually better than a full nazi. A leader who would have done half what Hitler did would have been better than Hitler. Unless you are thinking in terms of purity, and so you don’t actually care about how many people are killed, in which case you’ve fallen into what George Orwell, the democratic socialist, called the fallacy of saying that half a loaf is the same as nothing at all. If you’re hungry, half a loaf is still half a loaf.

A friend once compared it to the trolley problem, in which a person refuses to pull the lever that involves being a participant in an action they really dislike in order to prevent a much worse outcome. I’m not a big fan of the trolley problem as an actual test of ethical judgment, but I think the metaphor is good—it’s a question of whether a person who refused to act (pull a lever that would cause one person to die rather than five) feels that this failure to act is more ethical than acting. When I talk to people who are in this kind of ethical dilemma, it’s clear that they are balking at that moment of their grabbing the lever—they want the trolley to shift tracks; they don’t want Trump to get reelected; they just don’t want to pull the lever.

That was complicated, but all I’m saying is that it’s a question of whether people recognize sins of omission. They don’t object to Biden getting elected; they object to voting for him.

So, how has that worked out in the past? I can’t think of a time when refusing to vote because one candidate was half as bad as the other has worked to lead to a better political situation (but I’m open to persuasion on this), but I can think of a lot of times when it hasn’t. I’ll mention one. It happens to be a time that people could vote for half-nazis, and liberals tried to persuade voters to do exactly that.

It’s important to remember that the Weimar Communists could have prevented Hitler from coming to power by being willing to form a coalition government, but they wouldn’t because, they said, every other political party (including the democratic socialists) were, basically, fascists.

I’m not saying that compromising principles is always a good choice; a lot of people made the mistake of thinking that they could work with Hitler, that they should stay in his administration (or on his military staff) so that they could try to control him or, at least, direct him toward better actions. They couldn’t. Within a couple of years of his being installed as Chancellor, all the people in his administration who were going to try to moderate him were either fired or radicalized. It took longer with the military, and in that case the people who tried to control him were fired, strategically complacent, or radicalized. But it was the same outcome. There was no working with Hitler—there was only working for him.

If we want to prevent another Hitler, then we have to vote against him.

A good review of the book is

A good review of the book is