It’s common for people to complain about obstructionism and political paralysis in the abstract, and to blame politicians (or political parties) for those problems, but we rarely see how we, as voters, are rewarding obstructionism and thereby guaranteeing political paralysis. Obstructionism in a democracy only happens when it’s rewarded by voters, so, if we want it to stop, we have to stop rewarding it.

Of course, obstructionism only looks like obstructionism when the out-group engages in it. We don’t see our political party or leader engaged in obstructionism, but principled resistance. There are times when refusing to compromise is principled and good, but it’s rare that refusing to deliberate is principled. Yet it can present itself that way, particularly on issues that voters have made impossible for politicians to deliberate. Too often, political leaders declaring themselves so irrationally committed to an irrational policy that they refuse to engage in rational deliberation is seen as principled and decisive. It’s neither.

How we (not they) reward obstructionism is neatly exemplified in the December 2, 1980 session of the House of Commons, when Nicholas Ridley, Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office of the UK, gave a statement regarding what the British called the Falkland Islands.

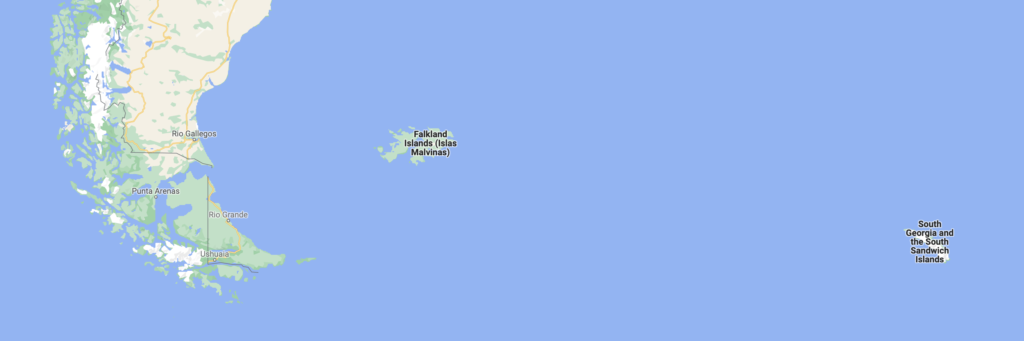

Background. The situation regarding the Falklands/Malvina was murky—both Britain and Argentina claimed sovereignty, and the issue had never been litigated in a world court. After the UN passed Resolution 2065 in 1965, recognizing that sovereignty was disputed, and calling on the two countries to find a solution, the UK couldn’t be certain that any such litigation would result a favorable decision. The UN Resolution framed the issue in terms of colonialism, specifically mentioning Resolution 1514, which was a “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples” (XV). Regardless of assertions on both sides about their indisputable right to claim sovereignty, the claims were disputable, since they were being disputed (this point will become sadly important).

It was also murky as to what policy Britain should pursue. This is also sadly important. Loosely, there were two kinds of action political leaders could advocate: formally acknowledge Argentine sovereignty of the region, or commit to “Fortress Falklands” (that is, openly commit to holding onto the islands, by military force if necessary).

Within each of those large categories were numerous other options. For instance, Britain might opt for a leaseback with Argentina while granting all islanders “patrial” rights (that is, the right to move to Britain as a British citizen), or a leaseback without those rights (which would mean about 200 of the 1800 or so islanders would not have British citizenship). The leaseback might be as short as twenty years or as long as eighty; islanders might be recompensed for their property, or not.

The “Fortress Falklands” option similarly had variations. The basic notion was that Britain would cease negotiating about sovereignty, an action that would require that the islands be fortified at least enough to deter Argentina from sending troops to occupy the area—such as regular navy patrols (so expensive that the Thatcher government had fought hard for the only ship in the area to be scuttled and for the UK to have no naval presence at all) or a standing military force on the islands. The airport would have to be expanded such it would be useable in case of an attempted occupation. The island economy would also have to be strengthened so that the islanders could be independent of Argentina in case it tried some kind of economic embargo.

The problem was that almost every possible long-term policy that involved British insisting on sovereignty was expensive, ranging from millions to billions of pounds, at a point when the Thatcher government was advocating a neoliberalist economic policy of cutting government expenditures back to the bone. Advocating spending, for instance, 7 million pounds on an airport for the 1800 islanders, when coal miners were told to stuff it, was not an argument likely to go over well with the large swaths of the public. And that estimate was a minimal expenditure.

Meanwhile, arguing for acknowledging Argentine sovereignty would mean either changing the recent law regarding “patrial” rights (which seemed unthinkable at the time, but ended up getting changed) and that had implications that were controversial among anti-immigration voters in the UK.

In short, there was no obviously perfect policy option, but a variety of choices with varied costs and risks. Therefore, in a perfect world, or even just a deliberative one, the House reaction to Ridley’s statement would have been to insist on deliberating the relative strengths, weaknesses, costs, and risks of the various options. It is, after all, supposed to be a deliberative assembly. That isn’t what happened.

There was one thing about the situation that was perfectly clear: an ambitious politician could not advocate any of the policy options without enraging some group. Insisting upon rational deliberation about the long-term costs and likely outcomes of any option did nothing other than offer a cue to an ambitious politician to rant and rage and strike poses like a bad actor in an amateur production of Shakespeare. The temptation was there because it looked as though the one non-controversial position (that would look good to many people and outrage no one) was to insist upon the principle of self-determination for the islanders without advocating any of the policies necessary to make that self-determination meaningful. And politicians of every party took that cue when it was offered. Lawrence Freedman snarkily summarizes the political rhetoric on the issue: “There was an obligation to accept that the islanders’ wishes were paramount when it came to negotiations with the Argentines but not when it came to expenditures” (Official I:151). And that is what happened when Ridley made his statement.

One of many strange things about political discourse is that, the more uncertain the situation, the more likely it is that politicians and pundits will insist there is no question at all. The answer, they insist, is obvious. For instance, several speakers insisted that it was obvious that Britain’s sovereignty claim was indisputable (as I said, it was disputed, so it was disputable). Ridley began his statement says, “We have no doubt about our sovereignty over the islands.” Yet Peter Shore criticized Ridley’s actions as though he was weak on the question of sovereignty, saying that even discussing leasing was “a major weakening of our long-held position on sovereignty.” Bernard Braine similarly characterized Ridley’s position as “yielding on sovereignty” and thereby undermining “a perfectly valid title in international law.” Of course, the title might have seemed to Braine to be “perfectly” valid, but that’s hyperbole. A title that has never been tried in international law is not perfect.

Ridley also said in his statement that “Any eventual settlement would have to be endorsed by the islanders and this House.” That’s an unambiguous statement, yet various speakers replied as though Ridley had waffled on the question of the ability of the islanders to veto any foreign policy they didn’t like, regardless of what the majority of British citizens felt. I emphasize that disproportionate amount of power because it would have been reasonable to say that some compromise is necessary. In 1977, the “Ridley Report” advocated harsh measures regarding workers in various industries, with comments like, “It must eventually be taken for granted that in order to meet the obligation plants must be closed and people must be sacked” (4) and “Effective action might mean that men would be laid off, or uneconomic plants would be closed down, or whole businesses sold off or liquidated” (4). Ridley’s report assumed that strikes were inevitable, and included estimates on how long the country could withstand strikes. So, when it came to workers in the UK, Ridley himself had no trouble telling far more than 1800 people that their wishes and desires could be completely ignored—neither he nor the Conservative Party was committed to the principle of self-determination, or unwilling to force people into compromises they didn’t want.

But, having said that he would give the islanders veto power, Ridley was treated as though he’d said the opposite, and various speakers from different parties asked leading questions (statements and speeches are prohibited in these circumstances, and only questions are allowed) demanding that Ridley take a hyperbolic stance on the issue. Peter Shore (Labour) said, “Will [Ridley] reaffirm that there is no question of proceeding with any proposal contrary to the wishes of the Falklands Islanders? [….] Will he, therefore, make it clear that we shall uphold the rights of the islanders to continue to make a genuinely free choice about their future, that we shall not abandon them, and that, in spite of all the logistical difficulties, we shall continue to support and sustain them?” (emphasis added) In other words, Shore was demanding that Ridley say that he will be an irresponsible political leader—a responsible leader sets limits on policies, largely on the basis of logistical difficulties. Political leaders (and voters) should pay careful attention to logistical difficulties, especially if those difficulties might require spending millions or billions of pounds.

Shore, a member at that time of the Labour Party, would hardly claim that it’s responsible to spend at least 17 million pounds on the Falklands and endanger relations with Argentina, at a time when “current and pending contracts with Argentina [were] worth over £240 million, as well as investment worth £60 million” (Freedman 49) and the UK economy was in such trouble. William Shelton (Conservative), David Lambie (Scottish Labour), James Johnson (Labour), Viscount Cranborne (Conservative) made similar demands for statements of intransigence. One of the most irresponsible statements was Douglas Jay’s “Why cannot the Foreign Office leave the matter alone?” As explained above, and as every member of Parliament knew, Britain had choices, it wasn’t obvious which one was best, and none was perfect, but something had to be done.

As various scholars have argued, and was admitted at the time, Argentina would eventually trigger war by occupying the islands because of misunderstanding the very mixed signals sent by Parliament, Thatcher’s government, and the Foreign Office. The way political leaders talked about the issue led to war when diplomacy might have solved the problem.

It’s quite likely that the speakers taking a bellicose stance had no desire for war over the islands, and I’m sure they didn’t realize that they were setting such a war in motion. But they were, not just by their posturing about a rigid stance on the issue of sovereignty, but by the combination of a rigid stance and no policy that would make a refusal to negotiate about sovereignty a plausible course of action. They had nothing to gain, politically, by arguing for any policy at all and much to lose. But, they had a lot to gain politically by arguing against any policy. In other words, they were engaged in obstructing not only any policies oriented toward a long-term solution to the situation, but any deliberation of the policies.

Newspaper reports the next day describe Ridley as having been “mauled” by the House, but I don’t feel sorry for him. He had several moments at which he could have been more honest and more accurate about the situation. He never mentioned the practical costs of improving the situation for the islanders, or of the costs of Fortress Falklands. At one point, a member (Frank Hooley) says, “Is not the Government’s argument that the interests of 1,800 Falkland islanders take precedence over the interests of 55 million people in the United Kingdom?” It’s an accurate characterization of the Thatcher approach to the situation, and of that advocated by Labour members like Shore. At that point, Ridley could have reminded the House of the costs of the course of action necessarily connected to what they were advocating, but instead said, “There need be no conflict between the two, especially if a peaceful resolution of the dispute can be achieved.” However the conflict was resolved would be expensive, and that means money would have to come from something that some other UK constituency wanted. Of course the interests conflict because interests conflict.

The members’ obstructionism was rewarded in the media. The Parliamentary Correspondent for The Times, for instance, repeated the arguments, endorsing them along the way, and said,

Seldom can a minister have had such a drubbing from all sides of the House, and Mr Ridley was left in no doubt that whatever Machiavellian intrigues he and the Foreign Office may be up to, they will come to nothing if they involve harming a hair on the heads of the islanders. (December 3, 1980, p 8)

Too bad The Times wasn’t so worried about the islanders’ hair that it advocated a reasonable discussion of policy options.

But, again, I don’t blame The Times, or the Members. Newspapers print what gets them readers, and politicians say what gets them votes. It was, ultimately, the voters who rewarded this kind of obstructionism. It is, also, voters who eventually pay for it. In the case of British voters, it was 288 dead, and 777 wounded, and at least 2 billion pounds. The UK gave the islanders patrial rights, and, in 2011/12, was spending 46 million pounds on the islands yearly.

But the miners could stuff it.