A while ago (probably several months), someone said they hated planning, and I’ve been meaning since then to write a blog post about it. It’s even been on my to-do list since then. To some people, that might look ironic–here I am giving advice about planning when I have been planning to do something for months and not getting to it.

That only seems ironic if we imagine planning to do something as making an iron-clad commitment we are ethically obligated to fulfill immediately. Thinking about planning that way works for some people, but for most people, it seems to me, it’s terrifying and shaming.

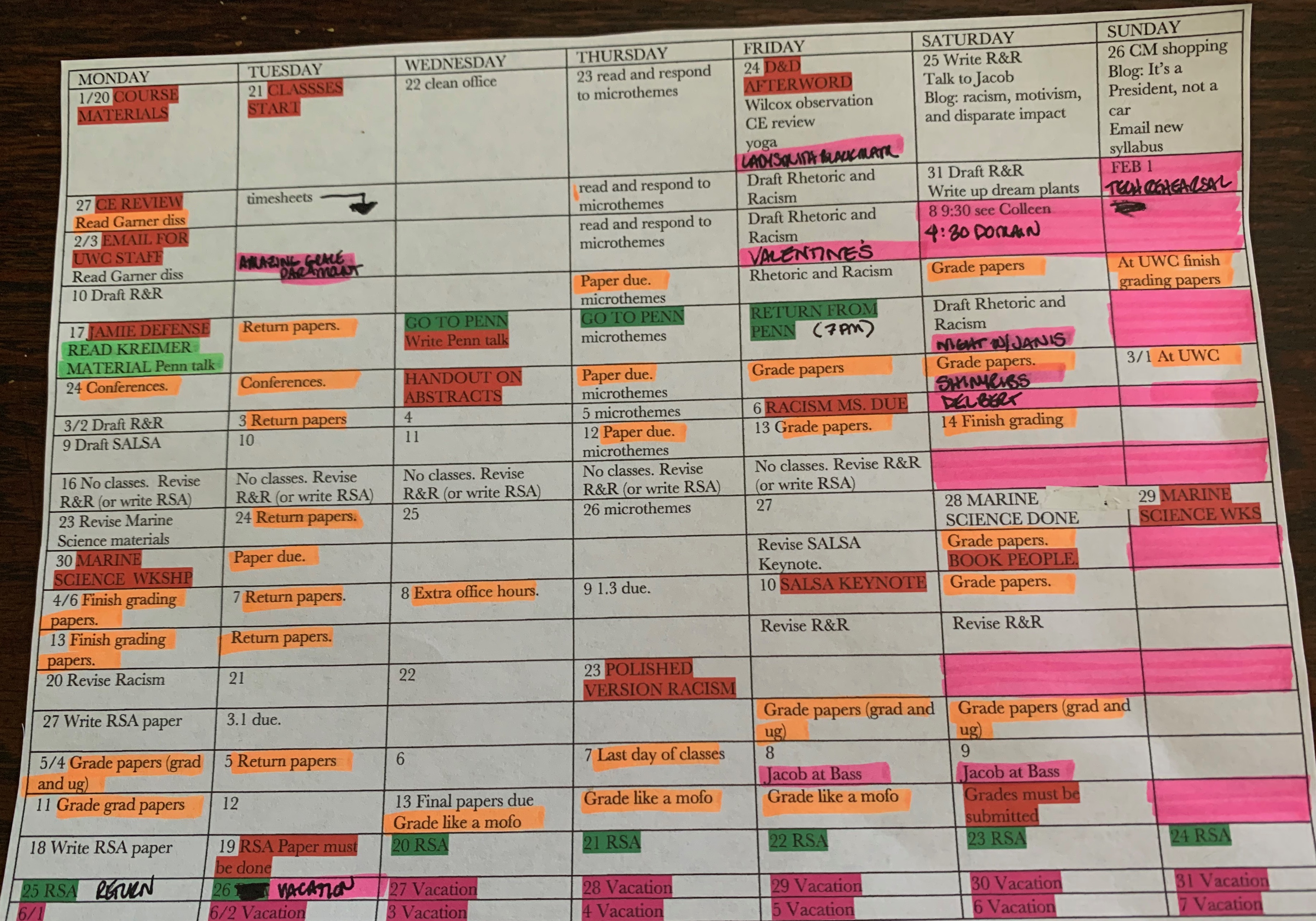

Planning isn’t necessarily a process that guarantees you’ll achieve everything you ever imagine yourself doing, let alone as soon as you first imagine it. Nor does planning require that you make a commitment to yourself that you must fulfill or you’re a failure. It’s about thinking about what must v. what should v. what would be nice to get done, somehow imagined within the parameters of time, cognitive style, resources, energy, support, and various other constraints. Sometimes things you’d like to get done remain in your planning for a long time.

There are people who are really good at setting specific objectives and knocking them off the list, who believe that you shouldn’t set an objective you won’t achieve, and who are very rigid about planning. They often get a lot done, and that’s great. I’m glad it works for them. Unfortunately, some of them are self-righteous and shaming because they assume that this system–because it works for them–can work for everyone. That it clearly doesn’t is not a sign that the method is not a universally valid solution, but a sign of the weakness on the part of people for whom it doesn’t work. They insist that this (sometimes very elaborate) system will work if you apply yourself, not acknowledging different constraints, and so they end up shaming others. They seem to write a lot of the books on planning, as well as blog posts.

And that’s the main point of this post. There is a lot of great advice out there about planning, but an awful lot of it is clickbait self-help rhetoric. There’s a lot of shit out there. There are some ponies. But there is so much shaming.

There are a lot of good reasons that some people are averse to planning—reasons about which they shouldn’t be ashamed. People who’ve spent too much time around compulsive critics or committed shamesters have trouble planning because they know that they will not perfectly enact their plan, and so even beginning to plan means imagining how they will fail. And then failure to be perfect will seem to prove the compulsive critic or committed shamester right. Thus, for people like that, making a plan is an existential terrordome. Personally, I think compulsive critics and committed shamesters are all just engaged in projection and deflection about how much they hate themselves, but that’s just one of many crank theories I have. Of course we will fail to enact our plan—nothing works out as planned—because we cannot actually perfectly and completely control our world. In my experience, compulsive critics and committed shamesters are people mostly concerned about protecting their fantasy that the world is under (their) control.

People who have trouble letting go of details find big-picture planning overwhelming; people who loathe drudgery find it boring; people trying to plan something they’ve never before done (a dissertation, wedding, trip to Europe, long-term budget) just get a kind of blank cloud of unknowing when they think about making a plan for it. People who are inductive thinkers (they begin with details and work up) have trouble planning big projects because it requires an opposite way of thinking. People who are deductive thinkers can have trouble imagining first steps. People who use planning to manage anxiety can get paralyzed when a situation requires making multiple plans.

I think planning of some kind is useful. I think it’s really helpful, in fact, and I think—if people can find the right approach to planning—it can reduce anxiety. But it is never to going to erase anxiety about a high-stakes project. And a method of planning shouldn’t increase anxiety.

Because there are different reasons that people are averse to planning, and people get anxious in different ways and moments, there is no process that will work for everyone. If a process doesn’t work for you, that doesn’t mean you’re a bad person, or you’ll never be able to plan; it just means you need to find a process that works for you. And, to be blunt, that process might involve therapy (to be even more blunt, it almost always does).

Here are some books that people trying to write dissertations have found helpful. Anyone who wants to recommend something in the comments is welcome to do so, and it’s especially helpful if people say why it worked for them. Some of these are getting out of date, and yet people still like them.

Choosing Your Power, Wayne Pernell (self-help generally)

Destination Dissertation, Sonja Foss and William Waters

Getting Things Done, David Allen (the basic principle is good, but it’s getting very aged in terms of technology)

Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey (another one that is getting long in the tooth)

I haven’t done much with this website, but the research is strong: https://woopmylife.org/

There are some things that can help. If you don’t like planning because it’s drudgery, then make it fun. Buy a new kind of planner every year. Use colors to code your goals. If planning paralyzes you because of fear of failure, then set low “must” goals that you can definitely achieve, and have a continuum of what should get done. Get into some kind of group that will encourage you. If you feel that you’re facing a white wall of uncertainty, work with someone who has done what you’re trying to do (e.g., your diss director) to create a reasonable plan. This strategy works best if they see part of their job as reducing anxiety, and if they have a way of planning that works with yours.

One of the toxically seductive things about being a student is that you don’t have to have a plan through most of undergraduate and even graduate school. You have to pick a major, but it’s possible to pick one not because of any specific plan–it’s the one in which we succeed (a completely reasonable way to pick a major, I think), and then we might go to graduate school in that thing at which we’re succeeding (it makes sense), and in graduate school we’re given a set of courses we have to take. The “plan,” so to speak, might be nothing more than “complete the assignments with deadlines set by faculty.” Those deadlines are all within a fifteen week period, and it’s relatively straightforward to meet them through sheer panic and caffeine. Then, suddenly (for many people), we are supposed to have a plan for finishing your dissertation, with deadlines that are years apart, for things we’ve never done—a prospectus, a dissertation. We have to know how to plan something long-term, with contingencies.

In my experience, planning in academia means being able to engage in a multiple timeline plan. Having one plan that requires that you get a paper accepted by this time, a job by that time, a course release by then increases anxiety. It seems to me that people tend to do better with an approach that enables a distinction between hard deadlines (if this doesn’t happen by that date, funding will run our) and various degrees of aspirational achievements.

I think this challenge is present in lots of fields: you can’t determine to hit a certain milestone, as much as hope to do so, and try to figure out what things you can do between now and then to make that outcome likely. Thus, there are approaches out there helpful for that kind of contingent planning. But, just to be clear, there are a lot that really aren’t.

I also think it’s helpful to find a way of planning that is productive given our particular habits, anxieties, ways of thinking. People who are drawn to closure seem to thrive with a method that is panic-inducing for people who are averse to it, for instance. So, it might take some time to find a method (it took me till well into my first job, but that was before the internet).

Writing a dissertation is hard; there is nothing that will make it easy. There are things that will make it harder, and doing it without a way of planning that works fits personality, situation, and so on is one. But there is no method of planning that will work for everyone, and there is no shame if some particular method isn’t working.