Great Feuds in Science describes a feud you don’t hear about much. If you do hear about it, you hear a strategically vexed version.[1] For years, there was a debate about the origin of life—what makes something come alive? It’s conventional to say that there were “two sides” on this issue—that’s how it was described in its era, and how it’s generally narrated.

What I want to do is use that example to show that describing a situation as having two (and just two) sides leads to a misunderstanding of the issue(s) even when everyone agrees that there are only two sides. That something can be mapped as two sides doesn’t mean that’s an accurate way to think about it. If we reduce complicated issues to two sides, then we ask: which group is right? And, since that’s the wrong question, we’ll get a wrong answer.

Because positions with important differences get blended into one, people end up engaging in the fallacies like straw man and nutpicking without realizing it.

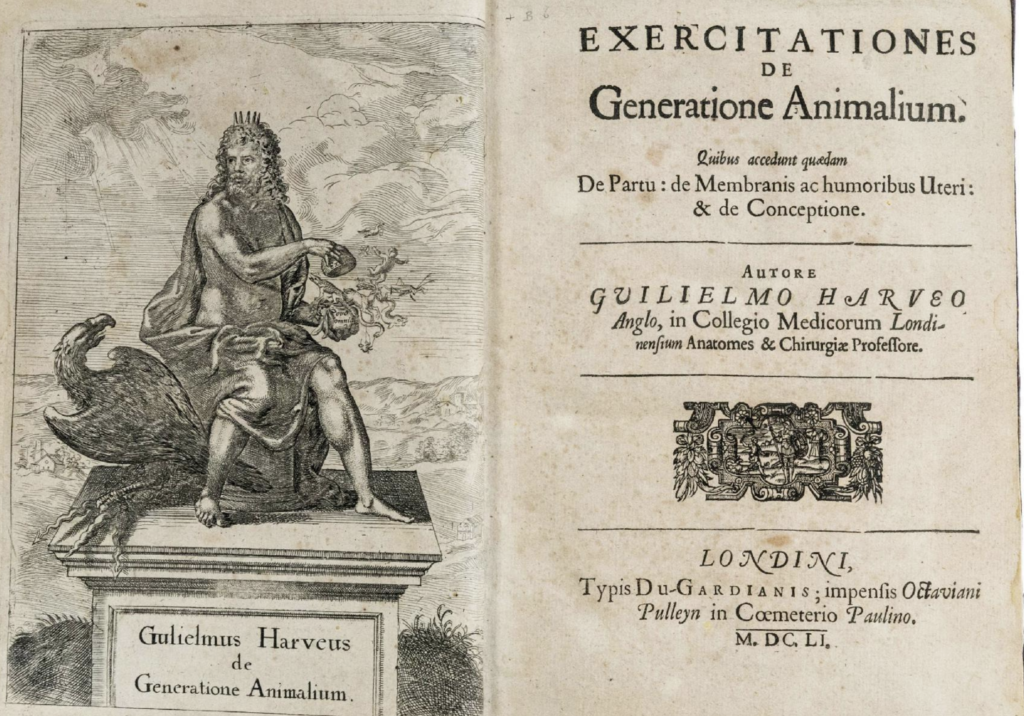

In the 18th century, it was conventional to believe that there were two camps on the issue of the origin of life: preformationism and epigenesis. Hellman summarizes preformationism: “all embryos existed, preformed though infinitesimally tiny, in either the egg or the sperm” while “plants were thought to arise from preexisting miniature organisms hidden in the seed” (68). In other words, if two humans have sex, there was in either the sperm or the egg (there was some disagreement on this point) a teeny, tiny person, a humonculus. That being just gets bigger as they grow. Preformationism was wrong.

Beliefs are not autonomous mobiles floating in space. They are entangled with other beliefs—as proof, conclusion, or (most commonly) both at the same time. Preformationism was both the evidence for and conclusion of the belief that God created all of creation at one moment. That argument runs like this: preformation is right because it supports the notion of a static creation and the notion of a static creation is right because preformation supports it. It’s a mobius strip of reasoning.

Hellman doesn’t give a precise definition of epigenesis, nor do various other sources, because it was defined through opposition—not preformationism. One version, advocated by Needham among others, was spontaneous generation , basically the idea that life springs from dead matter.

Needham boiled mutton gravy, put it in a container sealed with cork, and heated it to a point that people believed was enough to kill any living thing. And there was life that sprang up (worms). He was clear that he had proof. (He didn’t—part of my point in this post is that data is not proof.)

According to Hellman, atheists used Needham’s experiment to support their case. That’s the mirror image of the logical mistake that preformationists made. The atheist argument accepts the associations preformationists insisted were necessary–that preformation proves God’s static creation. Since they were wrong about preformation—which was supposed to be proof of God–, they were wrong about how creation happened, and therefore wrong about God. Notice that this is a valid argument only to the extent that the entire world of possible scientific, religious, and political beliefs is really a world of only two possible positions, and that preformationists were right in associating religious belief with preformationism. They were wrong. So were the atheists. Not because being an atheist is wrong, but because those associations were wrong, and Needham’s experiments were bad.

Voltaire argued that Needham was wrong (he was), but he did so with arguments no more rational than Needham’s. And, that Needham was wrong in arguing for spontaneous generation doesn’t necessarily mean he was wrong in arguing against preformationism, let alone wrong about creation or God. (As it happens, he was, but so was Voltaire.)

If you treat a complicated issue as two sides, then you can believe that showing any person (or specific claim) on “the other side” is wrong means you’ve shown that whole side is wrong about everything. You haven’t. You’ve misunderstood and misrepresented the issue. Both Needham and Voltaire were right that the other was wrong, but they were wrong in thinking they were right.

Here’s what I mean. An old, but I’ve come to think very useful, concept in argumentation is that affirmative and negative cases are different. We tend to conflate them. Or, more precisely, we tend to treat a solid negative case as though it’s a solid affirmative case.

An affirmative case is one in which I say that my policy, claim, or party is right. A negative case is one in which I say that your policy, claim, or party is wrong. An effective negative case is not a rational argument for an affirmative. If I believe that bunnies are communists, and you believe that they are Zoroastrians, we each have an affirmative case we need to make. (Bunnies are communists; bunnies are Zoroastrians.) If I make an effective negative case (you have not shown that bunnies are communists), I have not just shown that my affirmative case is true (bunnies are Zoroastrians). That’s the mistake that Voltaire made.

But, so very, very much of our public discourse makes Voltaire’s mistake. Both Needham and Voltaire had strong negative cases; neither had affirmative cases stronger than a weak sneeze.

If we ask the wrong question, we will always get a wrong answer. If we ask, which of these two groups is right?, we’re asking the wrong question.

If we assume that all of our policy options are defined in terms of two identities, or a continuum between them, then we are arguing policy no more rationally than Needham and Voltaire. We might be right that they are wrong, but that doesn’t mean that we are right that we are right. Their being wrong doesn’t make us right.

[1] You read about how Pasteur showed spontaneous generation was wrong. Various people, including Voltaire, had also shown it was wrong, but they did so in favor of a grand narrative that was just as wrong. People who want to have a narrative of science that is about truth-tellers opposed to religious bigots don’t like to talk about people like Voltaire. There are a lot of things they don’t like to talk about, like eugenics. Another binary we need to abandon is scientists v. bigots. If we could step away from talking about social groups, we might be able to talk about ways of reasoning and arguing in favor of policies/claims. I’d like that.