I wander around various dark corners of the internet, and find propaganda in all sorts of places.[1] And by “propaganda,” I mean Machiavellian compliance-gaining and uni-vocal discourse.

People who choose to rely on propaganda for their political information never think that’s what they’re doing. They sincerely believe that propaganda is what those suckers believe. Effective propaganda is good at persuading people that it isn’t propaganda—that’s its first task. Propaganda in a nation or community where people can choose what they consume can’t look like propaganda, or people wouldn’t choose to consume it. We don’t think we listen to propaganda, and—and this is really interesting– even if we recognize that we do listen to propaganda, we don’t think it has worked on us.

One of the ways that propaganda looks like not propaganda is by playing to the false rational/irrational split. The rational/irrational split says that you either reason from emotion, or you reason from, um, reason.

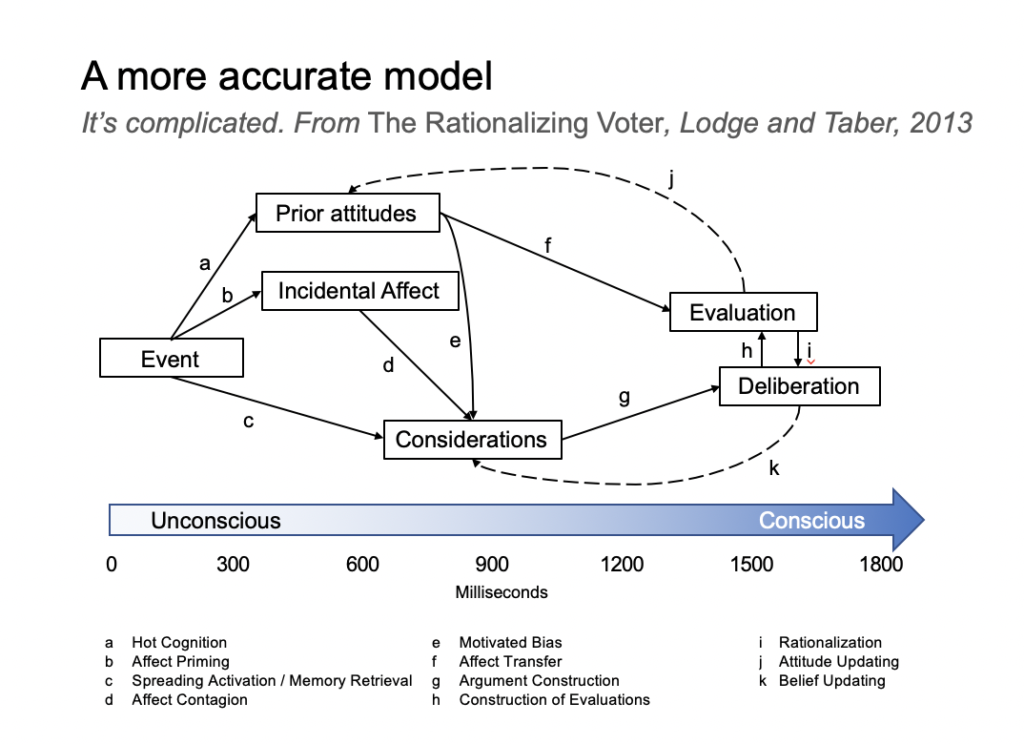

That isn’t what the last twenty years of research in cognition shows. It shows that decision-making isn’t monocausal, and that the process isn’t a binary of any kind. How we assess an argument is influenced by perception of in-group/out-group affiliation, beliefs about those groups, our sense of commitment/threat to the in-group (a combination of feelings and beliefs), how much the issue triggers/enables motivated cognition, how aware we are of our tendency to motivated cognition, various cues and triggers in the text and environment, memory, and various other factors. This is a good map of the processes, with conscious deliberation just h and i. The other factors are more or less unconscious (or intuitive), but that doesn’t mean they’re usefully described as emotional (they have a lot of cognitive content, and there is a logic to them) or logical.

Notice that neither the rational/irrational split, nor the false trichotomy of ethos/pathos/logos accurately describes this really complicated process. You can shove this model into the rational/irrational, or the ethos/pathos/logos, or the five parts of the mind, or the four humors, or lots of other taxonomies, but what you lose is what’s really useful about this model: the extent to which our assessments and decisions are influenced (perhaps restricted is a better word) by our pre-existing beliefs, and what we imagine our options to be.

And propaganda works by creating a very limited world of beliefs and options.

A really effective propaganda outlet is good at making its suckers believe that it is an essentially transparent medium, so that, even if we are at some point forced to acknowledge our reliance on propaganda, we underestimate how much of our world was constructed by that propaganda. We think we didn’t fall for it.

So, for instance, Tapping Hitler’s Generals is a collection of conversations that Nazi generals had while held captive in a house in Britain from 1943-45. They often talked about Nazi propaganda, with considerable contempt for the masses who fell for it. Yet they continued to believe in its central tenets(such as that the war could be won, even after the disaster of Stalingrad, see especially 44-45, 73), that the Allies would exterminate all Germans (46), that Germans were morally superior (50, 68), and they continued to support Hitler (61, 66, 73). Milton Mayer’s post-war interviews with Germans, and the interrogations of Nazi war criminals at Nuremburg show the same thing: people who know that they had spent years listening to propaganda still believed many of the lies they were told. Knowing that they listened to propaganda didn’t cause them to doubt their beliefs or judgment; they just rejected some beliefs.

And that is why propaganda is effective. Really effective propaganda doesn’t look irrational, because it looks as though it is arguing from good reasons and data. It seems true because it fits with what people already believe.

In a culture of choice, it says, they believe propaganda, but we are giving you the truth, and, even if we don’t, it’s okay because people like you have great judgment and can always recognize the truth. You are never mislead by us because you are too smart to be misled. The main move of propaganda—they are idiots, and you are too smart to fall for their propaganda—is how you get suckered.

When people ask themselves about whether their sources are propaganda, they ask all the wrong questions. They ask themselves:

- is this source saying things that are false?

- does this source have reasons?

- is this source overly emotional?

- are the claims of this source supported by experts?

Those are the wrong questions. Better questions are:

- what are the conditions under which I would decide my beliefs are wrong?

- if there was evidence that the major claims of this medium were wrong, would they tell me?

- does this medium accurately represent the best counter-arguments, or does it engage in inoculation?

If we can’t answer those questions with specific instances, especially that second one, then our beliefs are probably grounded in propaganda.

So, instead of feeling good about ourselves because our propaganda outlet has persuaded us that those consumers of that propaganda are bad, perhaps we should worry about whether our sources are propaganda?

[1] I don’t find it “on both sides,” since the very notion that the complicated world of political stances can be divided into two is how the skeezy salesman of bad decisions gets his foot in the door of democratic deliberation. The first thing a skeezy salesman says to a possible mark is, “I’m not a skeezy salesman because I’m not like that guy.” There is always a “that guy” who is worse, but it doesn’t mean this guy is good. Saying that “both sides do it” is a silly thing to say—partially because the next (fallacious) step is to say “both sides are just as much at fault” which is rarely true even if there are two sides, and secondly because there are rarely two sides. “Both sides”—meaning “liberal” and “conservative”—means pretending that neo-conservatives, neo-Nazis, libertarians, paleo-conservatives, neo-liberals, and conservative evangelicals are all interchangeable in terms of their rhetoric and actions. So, Daily Sturmer and The Economist have the same rhetoric. They don’t.