Once again, people are bemoaning the morass that is our political discourse, and, once again, blame is placed on the lack of civility. Then the conversation follows a deeply-rutted path: what civility is, whether there’s less of it than there used to be, and “which side” is more incivil, or who is justified in their incivility. It’s a route that can’t get us out of the morass, let alone toward better political disagreements, because incivility is the consequence and not the cause of what is really the problem.

The problem is the extent to which people think and talk about politics in terms of the rational/irrational split—a binary that is wrong in so many ways. To explain some of these ways, I need to start at a place the civility road evades: what is political discourse supposed to do in a democracy?

One answer is that political disagreements don’t actually do much of anything—it’s just a right: democracy is supposed to allow people to express their beliefs, so the ideal public discourse is one in which everyone is allowed to express whatever they think with no constraints.[1] This is sometimes called the “expressive” model of democracy. Another, sometimes called the “marketplace” model, is that public discourse is a bunch of people selling their policies—just as the marketplace always inevitably rewards the best product, so a free-for-all of people making whatever arguments will persuade others always results in the best policies.[2]

What if we instead imagined political disagreement as policy disagreement? What if we saw the purpose of public discourse as enabling us to come to decisions that are the most reasonable, given our very different needs, values, perspectives, opportunities; policies that distribute the burdens and opportunities of our shared lives in a reasonable way?

If we think about the purpose of public disagreement that way, then what matters isn’t whether someone is particularly nice when they make their argument, but whether their argument is reasonable. An argument that is dishonest, misleading, and fallacious isn’t transmogrified into an honest, accurate, and reasonable argument if it’s presented politely. It’s still a bad argument, and probably in service of a bad policy—if you can’t advocate your policy with accurate information, a fair representation of the opposition, and reasonable connections among claims, then there are probably better policies out there.

The incivility of our public discourse isn’t the cause of being able to have productive disagreements—it’s the consequence of our tendency to characterize anyone who disagrees with us as “irrational,” and that tendency is the consequence of how we think (or don’t think very clearly) about what “rational” should mean.

After all, what does it mean to have a reasonable policy argument? We often use terms like “rational,” “reasonable,” and “logical” interchangeably (although there is a reasonable argument for making a distinction—I’ll get to that in another post), and all three of those tend to part of a binary: rational/irrational; reasonable/unreasonable, logical/illogical.[3]

Definitions tend to be circular, depend on negation (being “rational” means not being “irrational” and vice versa) and muddled. Webster’s, for instance, defines “rational” as “having a reason” or “reasonable.” Notice that those two are actually very different. If I say, “You should be opposed to nuclear power because my I have a bunny named Fluffy,” I’ve given a reason. But we wouldn’t say that’s a reasonable argument. My statement gives a reason—it has the form of “claim because reason”—but the reason isn’t logically connected to my claim.[4] Even were the “because clause” true (I do have a bunny, and it is named Fluffy), I doubt any of us would say that’s a reasonable argument.[5]

But if “rational” means “reasonable,” what does it mean for something to be “reasonable”? Webster’s again offers two definitions that are relevant: “being in accordance with reason” and “not extreme or excessive” (I’ll come back to the second). “Reason” is “a statement offered in explanation”—so back to a form definition (and, once again, the nuclear power argument is reasonable); or “a rational ground or motive.” We’ve come full circle.

This simultaneously contradictory and circular definitions of “rational” isn’t the consequence of some failure on the part of Webster’s. The point of a dictionary like Webster’s is to show common usage, and common usage of the term “rational” has those qualities. For instance, we tend to use the term rational to describe some very different things: an argument, a claim, a person, a way of arguing, a way of thinking. For some people, a “rational” argument is not necessarily true—it just has a particular form—but the term is also sometimes used to imply that the argument is true. Some people use the term “rational” to mean an amoral assessment of means and costs (so, the argument runs, Hitler invading the USSR was “rational” insofar as it was the only way to achieve his ends). The most common sense about rationality is that it is not its opposite—a rational argument is not irrational, and “irrationality” is associated with emotion. So, a rational argument is not emotional, a rational policy is not grounded in feelings. That’s how one gets to the argument that Hitler’s invasion of the USSR was “rational”—considering the devastation to peoples, the morality of the cause or means are all deflected as about “feelings,” and therefore “irrational.”

And, of course, Hitler’s desire to invade the USSR was all about feelings. That’s pretty typical of the attempt to characterize rationality as an amoral and unemotional determination of the most effective means—it’s all in service of deflecting, suppressing, or ignoring the very present feelings. I have had more than one person shout at me that we needed to be “rational” about this situation rather than emotional. Since I wasn’t particularly far away, and therefore would have no trouble hearing them if they spoke in a normal tone of voice, there was no reason to shout, other than that they were very, very emotional at the moment.

Sometimes rational/irrational is described as a binary, meaning that the slightest bit of emotion taints the argument, person, policy, and so a “rational” person (etc.) has no emotion. And, obviously, that’s never the case. We wouldn’t be arguing about the policy or issue unless we had feelings that it’s important.

Policy decisions involve feelings of honor, hope, care, compassion, fear, anger, and they should. So, let’s just set aside the muddled notion that a rational argument is one devoid of feeling. A person devoid of feeling wouldn’t be rational; they’d be dead. (Even sociopaths have feelings—they just don’t have feelings of compassion for others.) It wouldn’t be rational to ignore feelings completely; if I am miserable any time I’m near the beach, it would be rational to take those feelings into consideration before buying a house on the beach.

Another way of thinking about rationality is in terms of the form of the argument. Some people assume that a rational argument has data, and they may even have a strong desire to privilege some data over others (e.g., numbers). Defining a “rational” argument as “one that has statistics” has the same problems as the bunny named Fluffy—that it has a particular form (claim plus statistics) doesn’t necessarily mean the statistics are valid. They may be fabricated, misleading, or irrelevant. A lot of arguments in which people cite statistics have the correlation/causation problem—according to the wonderful website “Spurious Correlations,” automotive recalls for issues with the air bags strongly correlates to the popularity of the first name “Killian.” There is, by the way, no causal relationship between those two phenomena.

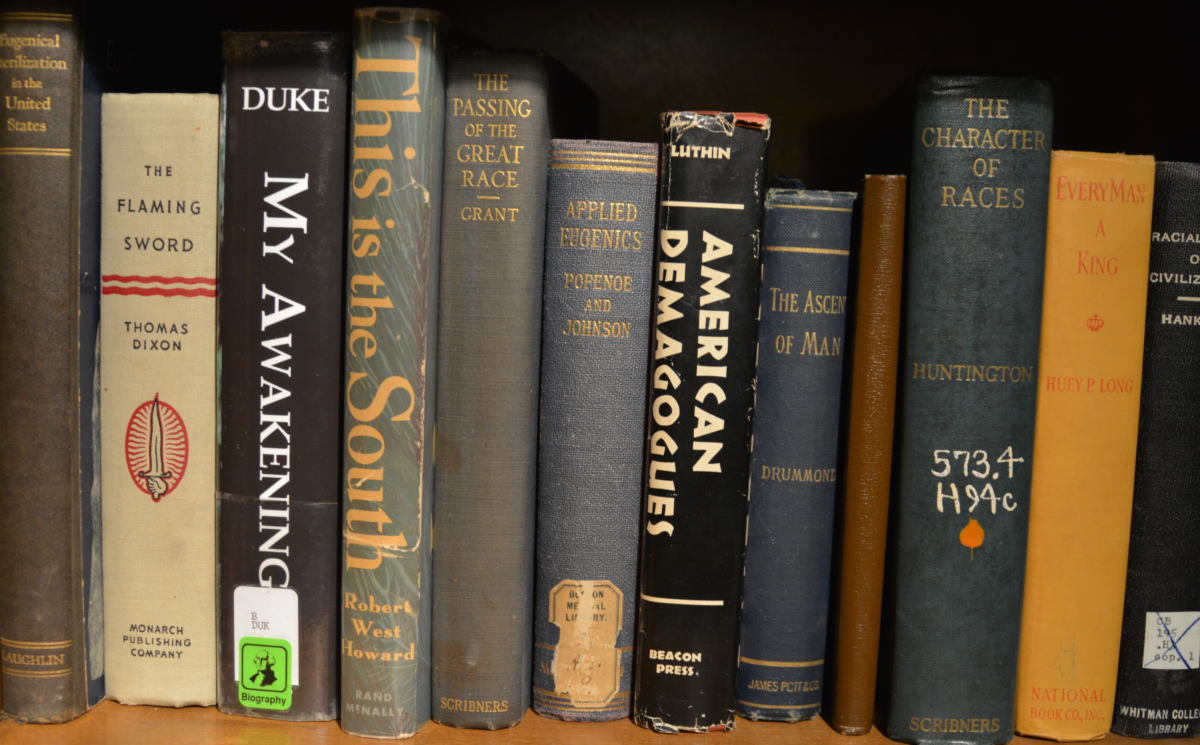

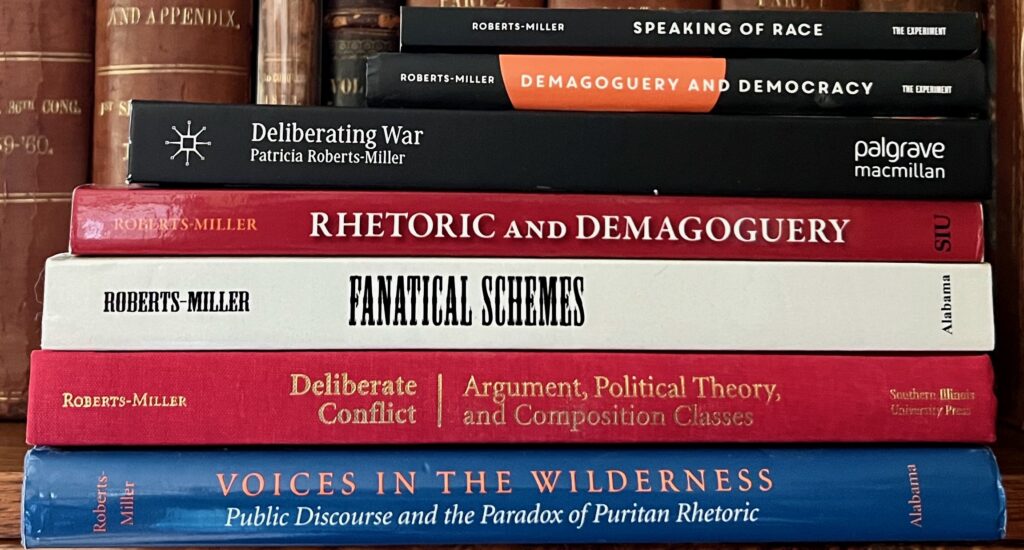

The idea that rationality is a trait that some people have is singularly pernicious and consistently anti-democratic. It’s often the consequence and cause of stereotypes about groups we don’t like: the dumbass “Southerner,” corrupt Irishman, skinflint Scot…and so on. In the 1830s it was common to argue that Catholics were incapable of independent reasoning (“rationality”) since they would just do whatever the Pope said, and so should be denied the vote. A similar argument was made about the Japanese Americans in 1942—that Shintoism meant they were incapable of independent thought and were therefore essentially traitors—an irrational argument on two grounds, including that not all Japanese Americans were Shintoist.

There have been moments when people assumed that “experts” are more rational about their own subject than non-experts (Walter Lippmann’s argument), a claim belied by “expert” witnesses whose testimony turned out to be tremendously biased and completely wrong (see especially Junk Science).

This isn’t to say that experts shouldn’t be treated with any credibility—this whole post is about rejecting a binary, and so I’m not arguing we should substitute another (there isn’t a binary between experts and non-experts, or reasonable v. unreasonable–both are more like a color wheel than a binary or continuum). It isn’t possible to reason without cognitive biases, but that isn’t to say all people (or all experts) are equally biased.

Because the rational/irrational binary is a…well…binary, if we value “rationality,” then we’ll attribute rationality to ourselves and our in-group (i.e., people like “us”), and “irrationality” to Them (people not like us).[6] We will consider it “irrational” to support an opposition candidate or policy, and therefore believe we shouldn’t listen to them. If They are irrational, then we should try to purify our media of Them; it’s even justified to silence them (since there is no merit to anything they have to say). We don’t have to take seriously anyone who disagrees with us.

Being “civil” about how completely irrational everyone is who disagrees with us doesn’t change the fact that we’ve got a public sphere in which we don’t listen to anyone who disagrees. It’s that assumption that every and anyone who disagrees with us is an irrational, immoral, doofus that causes the incivility.

The final way to think about rationality I want to mention is about rules. I’ll be clear: I’m on team rules. Sometimes. What matters is what the rules are—there are some ways of thinking about the rules that are just as harmful as any of the other problematic definitions above. For instance, rules of “civility” have often been used to silence important information, as when pro-slavery politicians voted for a gag rule about criticism of slavery–it was considered a violation of civility to criticize slavers. Neo-Aristotelians believed that a rational argument had to be derived syllogistically from a universally valid major premise; that was a kind of training not provided to women, so women were, by definition, incapable of a rational argument.

The “rules of logic” can be either usefully inclusive, or irrationally exclusive.

Scholars of argumentation still argue about what the rules should be (there’s an entire journal devoted to that topic), but there are a few points of agreement that will surprise the Logic Nazis out there.

Attacking someone’s character is not necessarily a fallacy, and attacking how they argue rarely is. Saying “You are lying” or “You are misrepresenting that source” is not ad hominem.[7] “You” statements do not constitute ad hominem. Ad hominem is a fallacy of relevance—it’s a way to change the subject. Saying that Trump is a bad candidate because he has a gold toilet is ad hominem (especially since he doesn’t and never has), but saying that he hasn’t put together a coherent healthcare plan in eight years is not. Saying that Harris is a bad candidate because she cackles is ad hominem; saying that she plans to reinstate a high capital gains tax is not.

Similarly, appeal to emotions (ad misericordiam) and appeal to expert opinion (ad verecundiam) are only fallacies if the appeals are irrelevant, such as that the cited person does not have relevant authority.

I’ll be clear: I’m on the side of thinking that we should not define rationality in terms of identity, affect, tone, kind of data, but on the relation of claims to one another and to the context of the disagreement. And I think those rules should be up for argument.

The set of rules I prefer isn’t particularly controversial—it’s pretty close to what anyone engaged in conflict resolution advocates. And, in my experience, it’s held up pretty well to historical cases (to my surprise). The shortest version of that set of rules is:

1) Whatever the standards of proof are (whether citation of religious texts, personal experience, myths, personal credibility, for instance, are allowed), they apply to all participants. That is, rules apply across groups. So, if I cite a relevant personal experience as evidence, then the relevant personal experiences of others are also evidence. If I condemn an out-group political figure or rhetor for shouting at babies, then I need to condemn in-group political figures and rhetors who shout at babies. I need to rely on evidence, and not signs.

2) People represent opposition arguments fairly and accurately, and people try to find the smartest opposition (no cherrypicking of outlier statements or rhetors, and no genus-species arguments about non in-group members).

3) Participants use data that can be falsified (not that they are falsified, but that it’s theoretically possible to imagine what data would contradict them, and therefore show the claims to be wrong).[8]

4) People are open to explaining their arguments and strive for reasonable relationships among claims, avoiding the major fallacies of form and relevance.

These are my preferences, largely the result of looking at train wrecks in public deliberation, but they’re open to argument. Whatever standards we have should enable judgment—they should help us identify the ways of arguing that tend to lead to train wrecks—while still being inclusive. There’s no point in setting standards only angels can meet, or restricting policy deliberation to a narrow set of experts. And the standards we set need to be based in the faith that there are often legitimate reasons for disagreement, that policy determination is complicated and uncertain, and that not every person who disagrees with us is a benighted irrational dupe.

[1] Actually, no one thinks that—it only takes a few examples before people start making exceptions. We all agree that some kinds of speech can be restricted in public and that private entities can greatly restrict speech; we just disagree about which restrictions should apply where. And we’re particularly protective of in-group speech.

[2] Yes, I’m being snarky.

[3] The rational/irrational binary is a relative newcomer to philosophy, running from Descartes and reaching its height among the logical positivists. Plato and Aristotle are often read as advocating it, as are various Enlightenment philosophers, but it’s worth remembering that Plato describes feelings—such as admiration of beauty or love—as ways of perceiving Truth. Aristotle’s logos v. alogos similarly doesn’t have the exclusion of affect or emotion that are part of our current rational/irrational binary.

[4] It’s theoretically possible that my overall argument is reasonable (there might be connections I could make if pressed, although none occur to me right now) but not in its current form.

[5] A lot of public arguments have exactly that form, and that logical flaw: “You should vote for Chester because 2 + 2 =4.” For reasons I’ve never entirely figured out, that sort of very unreasonable argument tends to be most persuasive when the “because clause” involves statistics. Even if the statistics are true—and sometimes they are—they’re often either irrelevant or only tangentially related to the main claim. As it happens, I don’t have a bunny, let alone one named Bunny.

[6] Sometimes people accept the idea of the binary, but flip the privilege, so they think “rationality” is bad, and “irrationality” is good—the Beats, Romanticists of various kinds. They tend to describe “rationality” as cold, number-driven, and passionless.

[7] Because I have a sick sense of humor, I think it’s hilarious when someone says, “You’re engaged in ad hominem because you’re attacking how I argue” since, by their definition, that statement is ad hominem. (It isn’t—neither is the original attack.) Or, sometimes they’ll say, “By engaging in ‘you’ statements, you’re engaged in ad hominem.” Notice the pronouns.

[8] And here the language needs to get a little precise. Many of my policy commitments come from my religious faith, and religious faith is, by definition, not falsifiable. So, my religious faith is not rational. My policy commitment to school lunches is grounded in Jesus’ commandment to care for the children, but the claims I make about free school lunches should be falsifiable—how many are provided, how many children need them, the consequences of providing lunches.

Another way to think about this “rule” is: are there any conditions under which you would change your mind about this? So, it’s whether there is any point in having a disagreement on that issue.