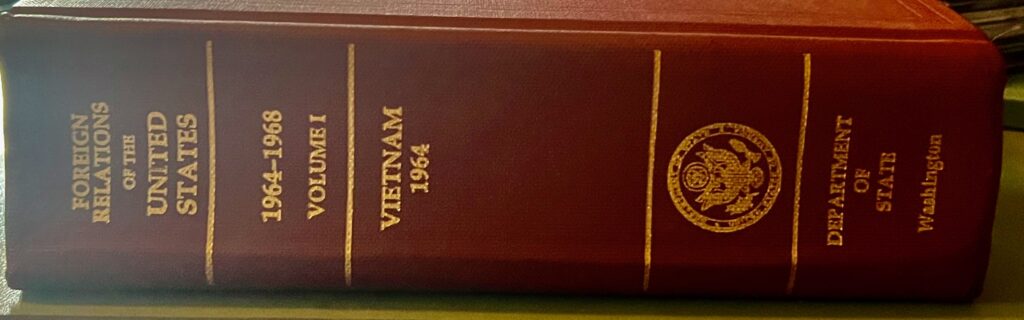

“Defeats will be defeats and lassitude will be lassitude. But we can improve our propaganda.” (Carl Rowan, Director of the US Information Agency, June 1964, FRUS #189 I: 429).

In early June of 1964, major LBJ policy-makers met in Honolulu to discuss the bad and deteriorating situation in South Vietnam. SVN was on its third government in ten months (there had been a coup in November of 1963 and another in January of 1964), and advisors had spent the spring talking about how bad the situation was. In a March 1964 memo to LBJ, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara reported that “the situation has unquestionably been growing worse” (FRUS #84). “Large groups of the population are now showing signs of apathy and indifference [….] Draft dodging is high while the Viet Cong are recruiting energetically and effectively [….] The political control structure extending from Saigon down into the hamlets disappeared following the November coup.” A CIA memo from May has this as the summary:

“The over-all situation in South Vietnam remains extremely fragile. Although there has been some improvement in GVN/ARVN performance, sustained Viet Cong pressure continues to erode GVN authority throughout the country, undercut US/GVN programs and depress South Vietnamese morale. We do not see any signs that these trends are yet ‘bottoming out.’ During the next several months there will be increasing danger than an assassination of Khanh, a successful coup, a grave military reverse, or a succession of military setbacks could have a critical psychological impact in South Vietnam. In any case, if the tide of deterioration has not been arrested by the end of the year, the anti-Communist position is likely to become untenable.” (FRUS #159)

At that June meeting, Carl Rowan presented a report as to what should be done, and he summarized it as: “Defeats will be defeats and lassitude will be lassitude. But we can improve our propaganda.” (FRUS #189). This is a recurrent theme in documents from that era, including military ones—the claim that effective messaging could solve what were structural problems. They didn’t. They couldn’t.

I was briefly involved in MLA, and I spent far too much time at meetings listening to people say that declining enrollments in the humanities could be solved by better messaging about the values of a humanistic education; I heard the same thing in far too many English Department meetings.

Just to be clear (and to try to head off people telling me that a humanistic education is valuable), I do not disagree with the message. I disagree that the problem can be solved by getting the message right, or getting the message out there. I’m saying that the rhetoric isn’t enough.

I am certain that there are tremendous benefits, both to an individual and to a culture, in a humanistic education, especially studying literature and language(s). That’s why I spent a career as a scholar and teacher in the humanities. But, enrollments weren’t (and aren’t) declining just because people haven’t gotten the message. There were, and are, declining enrollments for a variety of structural reasons, most of which are related to issues of funding for university educations. The fact is that the more that college costs, and the more that those costs are borne by students taking on crippling debt, the more that students want a degree that lands them a job right out of college.

Once again, I am not arguing that’s a good way for people to think about college; I am saying that the reason for declining enrollments isn’t something we can solve by better messaging about the values of a liberal arts education. For the rhetorical approach to be effective (and ethical) it has to be in conjunction with solving the structural problems. Any solution has to involve a more equitable system of funding higher education.

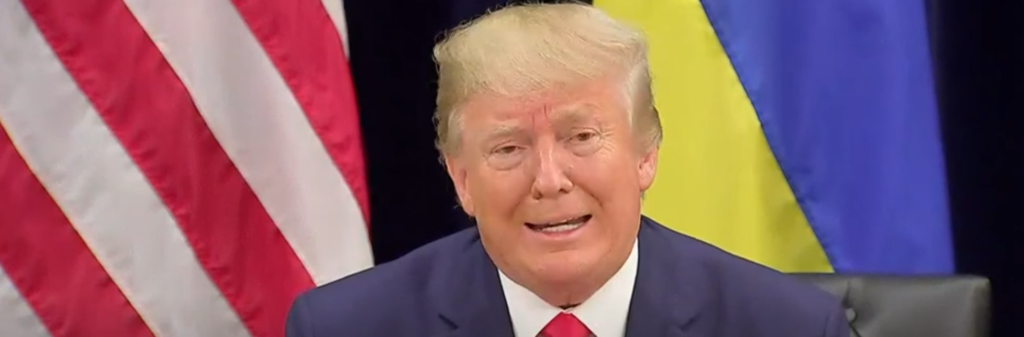

I am tired of people blaming the Dems’ “messaging” for the GOP’s success. I thought that Dem messaging was savvy and impressive. They couldn’t get it to enough people because people live in media enclaves. If you know any pro-GOP voters, then you know that they get all their information from media that won’t let one word of that message reach them, and that those voters choose to remain in enclaves. How, exactly, were the Dems supposed to reach your high school friend who rejects as “librul bullshit” anything that contradicts or complicates what their favorite pundit, youtuber, or podcaster tells them? What messaging would have worked?

The GOP is successful because enough people vote for the GOP and not enough vote against them. Voter suppression helps, but what most helps is anti-Dem rhetoric.

Several times I had the opportunity to hear Colin Allred speak, and his rhetoric was genius. It was perfect. Cruz didn’t try to refute Allred’s rhetoric; all Ted Cruz had to do was say, over and over (and he did), that Allred supported transgender rights.

From the Texas Observer: “Cruz and his allied political groups blitzed the airwaves with ads highlighting that vote and Allred’s other stances in favor of transgender rights. The ads, often featuring imagery of boys competing against girls in sports, reflected what Cruz’s team had found from focus groups and polling: Among the few million voters they’d identified who were truly on the fence, the transgender sports topic was most effective in driving support to Cruz, said Sam Cooper, a strategist for Cruz’s campaign.”

Transphobia is not a rhetorical problem that can be ended by the Dems getting the message right. Bigotry is systemic. Any solution will involve rhetoric, and rhetoric is important. But it isn’t enough.

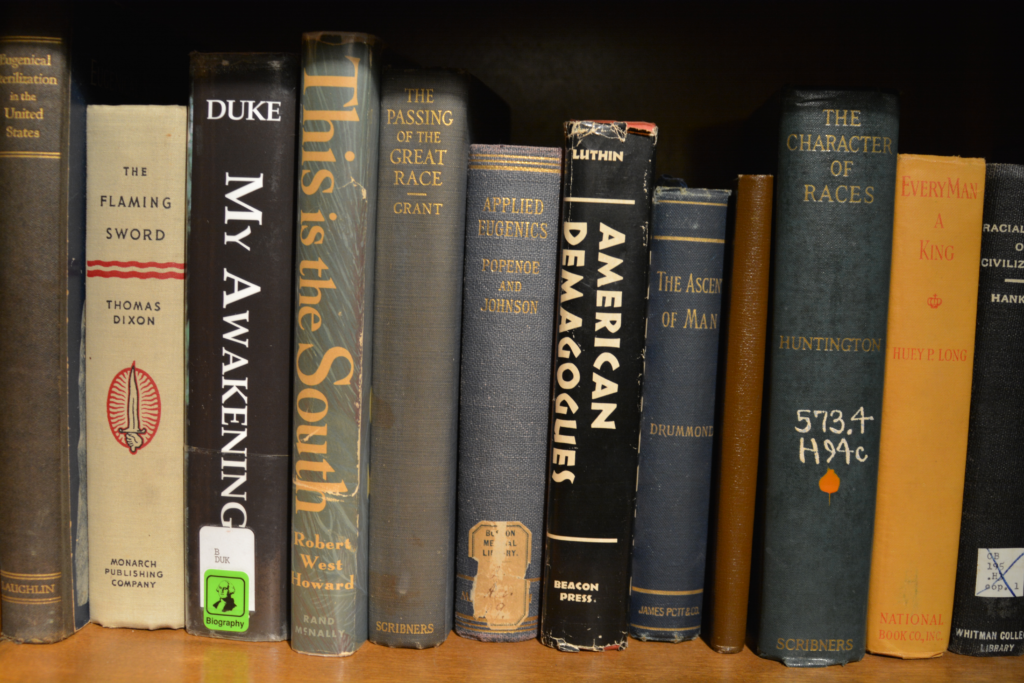

One of many weird things about politics is how people claim that their opposition to a political figure is a question of principle, but that principle only seems to apply to an out-group politician. Thus, if Chester embezzles, and you are anti-Chesterian, you are likely to try to make your position seem reasonable—and not just in-group fanaticism—by claiming that you’re opposed to dodgy real estate dealing on principle.

One of many weird things about politics is how people claim that their opposition to a political figure is a question of principle, but that principle only seems to apply to an out-group politician. Thus, if Chester embezzles, and you are anti-Chesterian, you are likely to try to make your position seem reasonable—and not just in-group fanaticism—by claiming that you’re opposed to dodgy real estate dealing on principle.