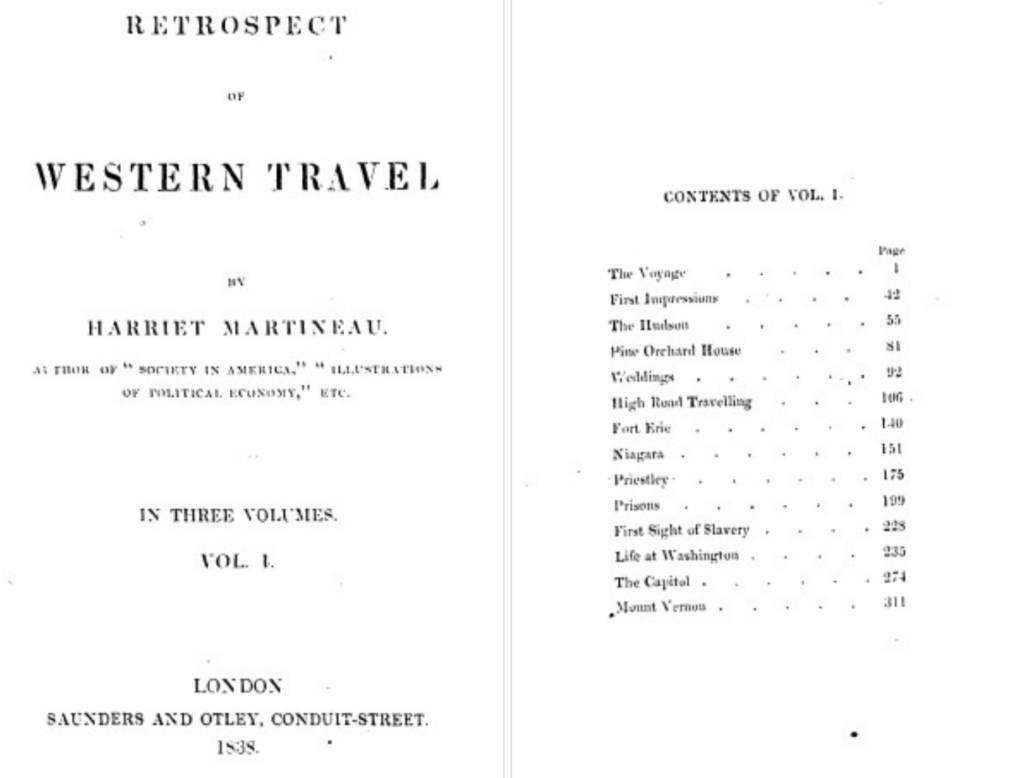

In the mid-1830s, the British writer Harriet Martineau visited the United States, and she found many slavers who were up in arms about the American Abolition Society having “flooded” the South with an anti-slavery pamphlet. She asked whether any of them had actually seen the pamphlet, and was met with outrage—how could she doubt the word of gentlemen? A lot of people didn’t doubt the word of those “gentlemen,” and the myth of the 1835 massive pamphlet mailing remains in history books (Fanatical Schemes, see especially 149-150, and Gentlemen of Property and Standing). It never happened. Martineau had already met with the people who had sent pamphlets to one post office, and who had agreed to send no more, so she suspected (correctly) that it hadn’t. She didn’t tell the slavers they were wrong, but she did ask what evidence they had, and their “evidence” was that their personal certainty, and the certainty of reliable people, all grounded in what their media said.

This mythical event was brought up in the next Congress, and people acted on the basis of a thing that never happened. The antebellum era had a lot of instances of that kind of thing—the fabricated Murrell conspiracy, various non-existent abolitionist plots, Catholic conspiracies against democracy.

People believed those myths for two reasons (which might actually be one): those myths were repeated endlessly by in-group (us) media, and those myths fit the overall narrative of that in-group media.[1] That overall narrative was one common to cultures of demagoguery: yes, we have a lot of problems, and it might look as though those problems are the consequence of slavery. But they aren’t! All of those problems are caused by the actions of Them.

Slavery had an almost endless number of ethical, practical, and rhetorical contradictions. People who claimed to be Christian rejected and deflected Jesus’ very clear commandment to “do unto others as you would have do unto you” (all cultures of demagoguery fail that test); they ignored, denied, and deflected very clear rules in Scripture about how to treat slaves; they reframed the very clear instructions about caring for the poor and weak as the need to enslave them. In short, Scripture is pretty clear: do unto others as you would have done unto you, take care of the poor and marginal. The problem for people who want to enslave, exterminate, or oppress others and yet want to see themselves as Christian is always how do we reconcile the cognitive dissonance?

We reconcile that cognitive dissonance through myths. And, oddly enough, the people who are now rationalizing a system that grinds the faces of the poor engage in the same non-falsifiable and extraordinarily self-serving myth in which slavers engaged: that people who are oppressed deserve their oppression.

This is an example of the just world model, the notion that bad things only happen to bad people, and that people who succeed earned that success, and that poor people are poor, not because of structural inequities, greed on the part of the wealthy, but because our system is too kind to the poor, making them choose to be poor.

From a Judeo-Christian perspective, the notion that we should be crueler to the poor in order to inspire them to be less poor requires a lot of intricate dancing in regard to Scriptural interpretation, with some ignoring or engaging in intricate explanations of anything Jesus said, in favor of open cherry-picking of the Hebrew Bible. It also requires a lot of intricate dancing in terms of data, with some serious cherry-picking. But, really, when people have decided that Jesus’ saying “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” doesn’t actually mean, well, doing unto others as you would have them do unto you, they can swallow a camel.

And they swallow a camel by swallowing circular arguments. Given that people whom we oppress are inferior, we can conclude they are inferior. Given that people who are poor deserve being poor, we can conclude that they deserve to be poor. Given that POC should be treated differently, we can conclude that they are different. Given that only inferior races are enslaved, we can conclude that those races are inferior. Given that we need to believe that slaves are happy, slaves are happy.

There are similar myths now: the American military is unbeatable, the free market solves all problems, government does everything wrong, cutting taxes boosts the economy, if you have enough faith you will be healthy and wealthy. People who are or were deeply committed to those myths have (or had) to explain slave rebellions, military quagmires, famines, situations in which even libertarians want the government to intervene, such as the Tea Party political figures who were outraged with what Obama did in 2008, but are now voting for a bigger bailout.

Failure presents people, and a community, with an opportunity to reflect sensibly on what we’ve been doing and thinking. The collapse of a relationship, failing a test, getting fired–these are all opportunities for us to tell stories about ourselves in which we behave differently.

Or not.

I had a friend who kept getting dumped because, his girlfriends said, he was too critical. I tried to suggest that maybe he should be less critical, but he insisted women were wrong not to appreciate how he was trying to help them. I used to have friends who lost money on timeshares multiple times. Maria Konnikova’s fascinating The Confidence Game describes how con artists con the same people multiple times.

Instead of reconsidering our commitment to an ideology, narrative, or sense of ourselves (a path that would admitting to people we were wrong, losing face, reconsidering all sorts of beliefs and relationships) we have the option of treating this situation as an exception. And it’s an exception either because of a lack of will—so if we recommit to our problematic ideology with greater will, then it will work. In other words, instead of the failure of a policy or ideology being an indication we should reconsider it, the problem is that we didn’t beleeeeeve in it strongly enough, and the failure is proof that it was the right course of action all along.

(No matter how times I see people react that way—and it happens in all the communities I’ve studied that ended up in train wrecks—it surprises me.)

Recommitting with greater will is almost always paired with scapegoating some group. They are the reason that our flawless plan keeps failing. And because They are so cunning and nefarious, we are justified in more extreme measures.

Normally, we tell ourselves and anyone who will listen, we would be kind to slaves, take care of the poor, respect the law (and so on), but we are forced to be heartless and suspend laws by Them. And what continually surprises me about the effectiveness of this scapegoating is how completely implausible the scapegoats are. Slavers picked on abolitionists—who, at the time they started getting scapegoated, were a tiny group of mostly Quakers. Hardly very threatening, and extremely unlikely to be fomenting race war.

Mid-19th century fantasies of a Catholic conspiracy to overthrow the United States involved a highly improbable collaboration among Irish, Italian, and German Catholics (the Irish wouldn’t even let the Italians worship with them in New York, let alone share political power) led by the Hapsburg Emperor and the Pope.

The Nazi fantasy about Jews had them as both communists and capitalists, a neat trick, and was persuasive enough that people accused any critic of Nazism of being either a Jew or a stooge of the Jews. As the scholar of rhetoric Kenneth Burke pointed out, that there appears to be a contradiction was taken by true believers as proof of the cleverness of the Jews.

Rush Limbaugh scapegoats liberals, who are “the ruling class.” As with the scapegoating of abolitionists or Jews, this scapegoating is simultaneously an elaborate and contradictory narrative, in which government employees, university professors (especially in the humanities), and environmentalists (hardly people with a lot of economic or political power), funded by George Soros and Bill Gates, are more powerful than actual billionaires who are actually in political office.

That this narrative is implausible and incoherent—if libruls were that powerful, they wouldn’t be grading first-year composition papers—just shows the cleverness of the libruls (as the apparent impossibility of an effective conspiracy of abolitionists, Catholics, Jews was evidence of the brilliant plan). Libruls are like the evil villains in old movies, who, instead of just shooting the hero, create Rube Goldberg machines to kill the hero and his sidekick.

The inchoate nature of the conspiracy (what, exactly, is the goal of the librul conspiracy? To work in the Post Office? Surely clever people would come up with a better endgame than that) means that Limbaugh can’t be proven wrong, that anything and everything can be blamed on the ruling elite, and no evidence that the GOP is actually the problem needs to be considered.

The American Anti-Slavery Society never flooded slave states with pamphlets; the problems with slavery weren’t caused by abolitionists.

[1] “In-group” doesn’t mean the group that’s in power, but the group people are in.