I’m often asked this question, and the answer is: it depends on the nature of their support, what we mean by “useful/effective,” and what we mean by “satire.”

1) Why do people support Trump?

There are, obviously, many reasons, and sometimes it’s a combination. But, for purposes of talking about satire’s effect, I’ll mention five:

A) Political Sociopathy (some people call it “political narcissism”). These are people who support Trump because they believe he will pass policies that will benefit them in the short run—lower taxes, eliminate environmental and employment protections, protect the wealthy from accountability, privatize public goods, and so on. They don’t care what the consequences will be for others, or what the long-term consequences might be—they only care that it will benefit them (they believe). Hence sociopathy.

B) Eschatalogical Understanding of Politics. This way of thinking isn’t necessarily explicitly religious—a certain kind of American Exceptionalism as well as Hegelian readings of history are also in this category, even if apparently secular. It reads history as inevitably headed toward [something]. That “something” might be: American hegemony, world capitalism, the return of Jesus, Armageddon, racial/ethnic domination, fascism, a people’s revolution, in-group dominance. People with this understanding don’t care about politics in terms of reasonable disagreements about policy, or even about specifics, but in terms of the apocalyptic battle or necessary triumph.

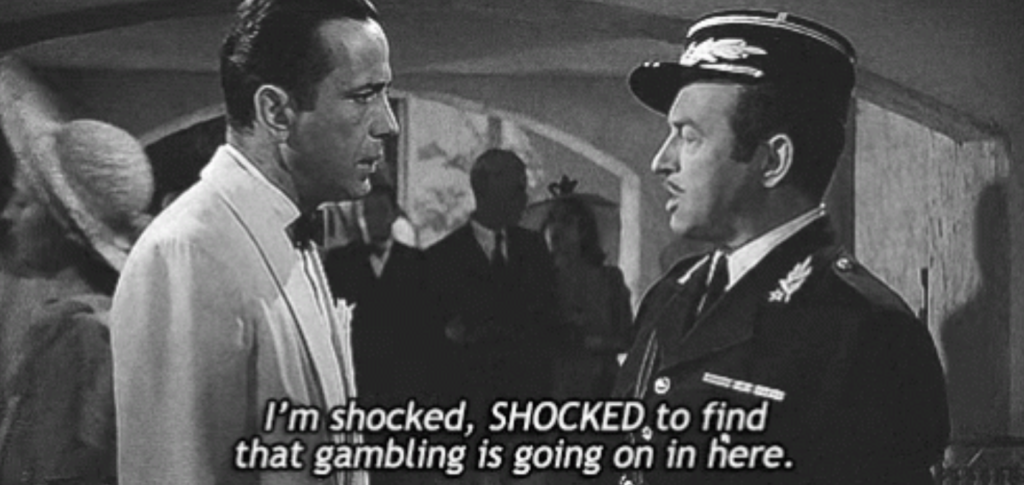

C) Resentment of Libs. (Stiiginit to the libs) These are people who support anything—regardless of its consequences even for them—that they believe pisses off “liberals.” That “liberals” are a hobgoblin, and that this orientation leads to “Vladimir’s Choice” doesn’t much matter.

D) Charismatic Leadership. This is a relationship that people have with a leader (sometimes several leaders). They believe that the leader is a kind of savior (the sacralized language is often striking), an embodiment of the in-group, who should be given unlimited power and held unaccountable so that they can “fight” on behalf of real people like them. (Charismatic leadership is often some kind of authoritarian populism—maybe always.

E) Purity politics. This group includes people who are radically committed to banning abortion—although there are policies that demonstrably reduce abortion, these people refuse to support them because they believe those policies (e.g., accurate sex education, access to effective birth control) are also sinful. Supporting birth control isn’t radially pure enough for them—that their policy will result in deaths in the short term doesn’t matter to them. They refuse to be pragmatic about short-term improvements or short-term devastation. People who refuse to vote for opposition candidates because that party or candidate isn’t radical enough are also in the category.

One characteristic shared among all of these kinds of supporters–in my experience is a tragic informational cycle—they refuse to look at anything that contradicts or complicates what they believe about Trump. They only pay attention to pro-Trump demagoguery because they believe that the entire complicated world of policy options and disagreements is really a tug-of-war between two groups. (A lot of people who aren’t Trump supporters think about politics that way–it isn’t helpful.)

2) Useful/Effective at what?

A) Persuading the interlocutor. People often assume that the point in engaging someone with whom we disagree is to get them to adopt our point of view.

B) Persuading bystanders. Sometimes, however, we aren’t trying to persuade the person with whom we’re disagreeing, but others who might be watching the disagreement.

C) Getting the topic off of Trump. Often, we’re just trying to get them to drop the subject, to let us enjoy dinner, a holiday, a coffee break, or whatever without talking about Trump, or taking swipes at the hobgoblin of “libs.” In other words, just get them to STFU about that topic.

D) Undermine the in- and out-group binary. We might want them to recognize the harm of their support for Trump and/or his policies—that is, to persuade them to empathize with an out-group.

3) What do we mean by “satire”?

The loose category of satire can mean: stable irony (a statement with a clear meaning that is not the literal statement—saying, “Great weather” in the midst of a nasty storm); unstable irony (the rhetor clearly doesn’t mean the literal statement, but it isn’t clear what they do mean), parody (which might be loving, as in the case of Best in Show, or critical, as in the case of much Saturday Night Live sketches about politics), or Juvenalian satire (scathing and often scatological). (Wikipedia has a useful entry on satire.)

So, the short answer to the question about effectiveness of satire on Trump supporters is: it depends on the kind of supporter, what effect we’re trying to have, and what kind of satire we use.

Many people object to satire because they assume that it’s insulting, and believe we should always rely on kindness and reason. But, as Jonathan Swift famously said: “Reasoning will never make a Man correct an ill Opinion, which by Reasoning he never acquired.” (For more on this quote and various versions, see this.) This is not always true, but it is true that a person has to be open to changing their mind for a reasoned argument to work. And not everyone is. So, if we’re talking to a Trump supporter who is open to changing their mind—that is, whose beliefs about Trump and Trump’s policies are falsifiable–then satire might not be the best strategy. But, to be blunt, I haven’t run across a Trump supporter whose beliefs can be falsified through reasoned argument in a long time.

The first category—the person who is in it for their own short term gain, and who might actually hate Trump—can seem to be “rational” insofar as they’re engaged in an apparently amoral calculation of costs and benefits (in my experience) is generally grounded in some version of the “just world model.” (That people who are wealthy/powerful/dominant deserve to be wealthy/powerful/dominant.) So, their reason for supporting policies that benefit them in the short-term isn’t falsifiable. They can be persuaded, sometimes, on very specific points about specific policies. Sometimes. Satire certainly doesn’t alienate them (although it might piss them off); it neither strengthens nor weakens their support.

Similarly, people whose support comes from an eschatological view of history/politics have a non-falsifiable narrative (they’re very prone to conspiracy theories), and, in my experience, have long since dug in. So, similarly, satire neither strengthens nor weakens their support.

The “stigginit to the libs” type person sometimes change their mind about Trump when they or someone they love gets harmed by Trump’s policies, so—sometimes—their support can be falsified by personal experience. But reasonable argumentation is right off the table—they like that Trump critics get frustrated with how unreasonable they are. (And, often, they have an unreasonable understanding of reasonable argumentation.)

Satire can increase their resentment of “libs,” especially if it hits close to home, but it isn’t as though some other rhetorical strategy would work. In theory, what should work would be some strategy of rejiggering their sense of in- and out-groups, or that creates empathy for an out-group, but I’m not sure I’ve seen that happen short of direct personal experience.

Satire, including the Juvenalian, can shame some people into shutting up, or allowing a change of subject, but I think other strategies are more effective (like refusing to engage). It can also have an impact on observers, but whether satire will cause them to feel sorry for the Trump supporters, get mad at libs, or distance themselves from Trump support/ers varies from person to person.

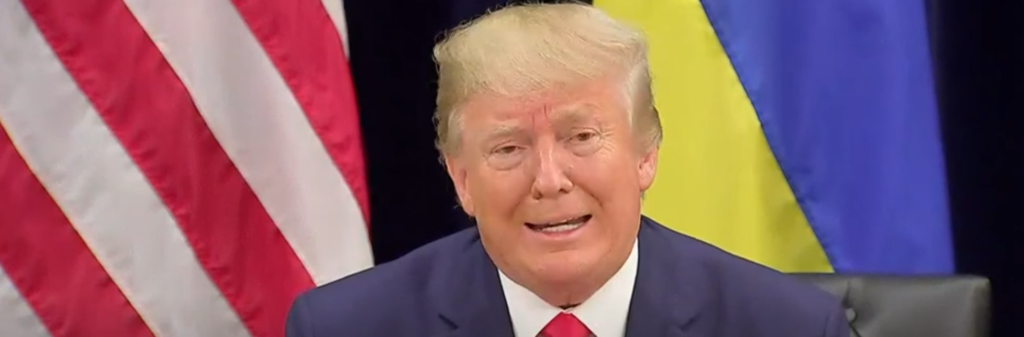

Satire can be very effective for people in a charismatic leadership relationship because it emphasizes that they look foolish. Their fanatical commitment is not, as they want to see it, a deeply personal and reciprocated loyalty, but gullibility. They’ll deflect by projecting their own fanatical commitment onto “libs,” and so it can be useful to insist that it stay on the stasis of their commitment. After all, it doesn’t matter if there are people equally fanatically committed to Biden or whoever—two wrongs don’t make a right. Biden supporters might howl at the moon and eat broken glass; that doesn’t mean that fanatical support of Trump is reasonable.

That Biden supporters might be wrong about something doesn’t mean Trump supporters are right. (And vice versa. Our political world is not, actually, a tug-of-war between two groups.)

And that points to one problem with satire of a group—what’s wrong with our political discourse is the fundamental premise that politics is a zero-sum battle between two groups. So, any satire that confirms that premise is, I think, problematic, and much of it does.

The final group is the purity politics folks. For those people, politics is a performance of purity; there’s a kind of narcissism to it. I don’t know whether satire would do much either to shame or persuade them—personally, I’ve never found that kind of person open to persuasion (regardless of where they are on the political spectrum).

So, to answer the original question: it depends.