There is a narrative that our system of policing is fine; there are just a few bad individuals in every group. That metaphor belies the narrative. Bad apples corrupt a system. As has been shown by representatives of police unions saying that they cannot do their jobs if they are held accountable for killing people in their custody, escalating violent situations, or assaulting people who have done nothing wrong, the system doesn’t allow for justice. Even the defenders of police violence are admitting it’s a job that can’t be done if police are held to the same laws they’re supposed to be enforcing. Police violence isn’t a problem of individuals who choose to do something they know is wrong; it’s about the selection and training of police, how juries are selected, how prosecutors tolerate lying, how bail works (or doesn’t), SCOTUS rulings. We have systemic police violence.

Focussing on Derek Chauvin is simultaneously important and trivial. He isn’t important as an exceptional individual because he isn’t exceptional. If we think he’s exceptional, we miss the point. But that doesn’t make him trivial. He’s important because he’s a sign of how the system operates. While Chauvin should be punished, throwing him out of the police, putting him in jail, that won’t end the problem.

Trump is the Chauvin of demagoguery.

There are people wringing their hands about Trump, including some of the very people who created the rhetorical and media systems that took him on the escalator to the Presidency. They reject Trump, but they haven’t rejected their own demagoguery or their participation in the demagogic media system that enabled his rise.

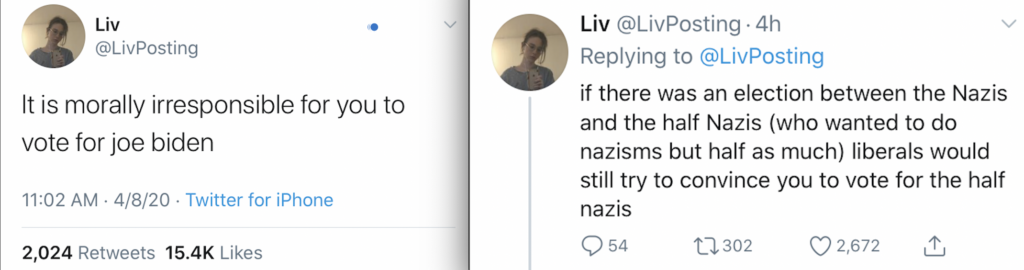

Trump is important, but not because he’s unique, and not because of his individual intentions. They’re bad; they’re murderous and vindictive and lawless, and he has no intention of being held accountable. And he persistently engages in demagoguery–it’s not only how he argues, but how he governs. But making him the problem, as though we can solve our political problems by making sure Biden gets elected, makes no more sense than thinking police violence has ended now that Chauvin is fired.

Jeffrey Berry and Sharon Sobieraj, in their deeply troubling The Outrage Industry, argue that, “once a candidate is in office, outrage continues to be a path to career advancement [because] research shows that members of Congress who are more extreme in their politics receive more coverage in the mainstream press” (179). Unfortunately, they have the data to support that claim. The media rewards demagoguery with free publicity.

This wasn’t surprising to me. It confirmed a crank theory I’d had since I was in Berkeley in the late seventies and eighties. Or, more precisely, the era when I gave up on TV news. I gave up on TV news for a few reasons.

First, I did the math. In a half-hour news program, there would be fluff, sports, weather, and ads. A half hour would get about six minutes of actually useful news. At that time, the LA Times was a great paper. I could spend that half hour reading the LA Times, and be much more usefully informed than the half hour watching the news. There was also California Journal (it might still exist), a journal with thoughtful bi-partisan information about politics.

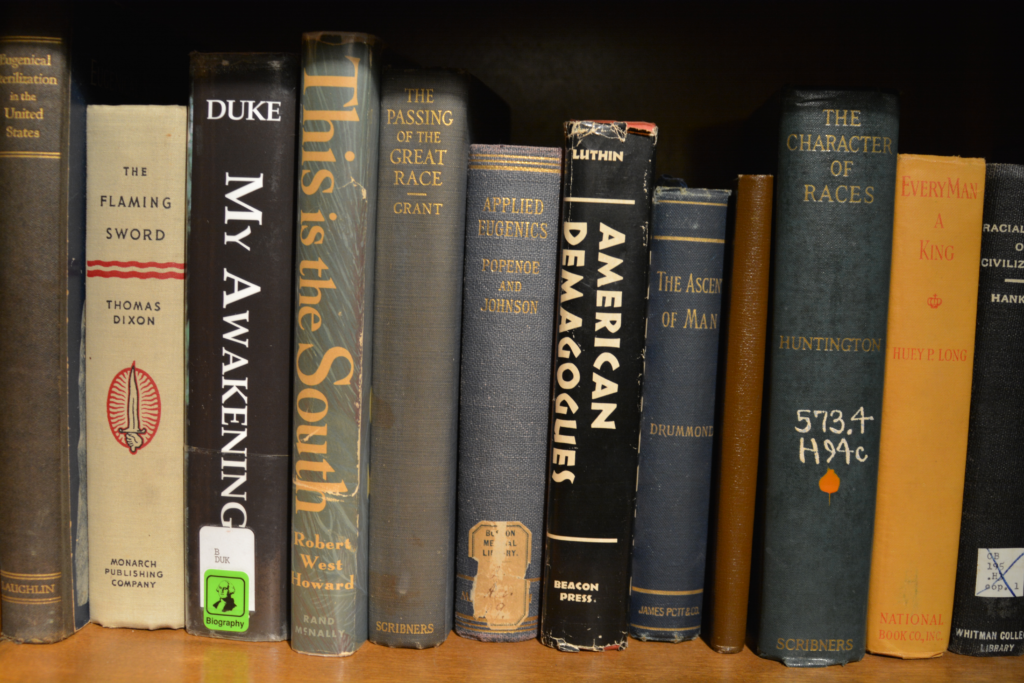

Second, even if I abandoned half-hour news programs, and tried to watch longer ones, they were no better. They brought on speakers, but they didn’t bring in the major figures. For instance, at that point Jerry Falwell had a smaller following than, say, the leader of the PCUSA or ELCA (mainstream Protestant organizations). But, when there was a question about religion, media brought on Robertson or Falwell.

Similarly, when it came to issues of race, they’d bring on Al Sharpton, at that point a much less important figure than any of the members of the Congressional Black Caucus.

The “problem,” from a ratings perspective, was that the leader of a major mainstream Protestant church would say something reasonable, nuanced, and calming; Robertson or Falwell would be polarizing. Some people would hate them; some would love them. But no one would think that what they were saying was too complicated or nuanced to understand. And no one would listen to an interview with them without being outraged. The nuanced, carefully articulated, and calming response on the part of someone who actually (at that time) spoke for more people that the demagogues Robertson or Falwell wouldn’t get the demagogic (us v. them) connection that was more profitable in terms of viewer loyalty that Robertson or Falwell got.

There was a slightly similar “problem” about representation when it came to race. Or, maybe, more accurately, there was the same problem, but with different consequences. My Congressional Rep was Ron Dellums, a fearless badass, and smart af, including about his rhetoric. That was true of most (all?) of the members of the Congressional Black Caucus. Any one of them spoke for more people than Sharpton did at that point. But the media went to Sharpton.

The irony is that, as far as I can tell, Dellums’ policy agenda was identical to Sharpton’s. So this wasn’t about the media fulfilling the role it often claims of being important for democracy. This was about profiting on the basis of racism, and thereby reinforcing racism. Someone like Dellums would have troubled racists’ perceptions of what black political figures were like. Dellums would have outraged racists in an uncomfortable way that meant they changed the channel. Sharpton didn’t.

This is no criticism of Sharpton. He was and is much more complicated than the “Sharpton” that was invoked (and still is) on reactionary and racist media. The problem isn’t that he went on major media and argued for his view. It’s great that he took that opportunity. The problem is that racist systems try to look not racist by engaging in rhetorically and economically profitable tokenism. Sharpton was right to go on those shows. Those media were wrong for not giving equal time to Dellums, Jordan, and various members of the Black Caucus.

And viewers were wrong, and racist, for not rejecting tokenism. This isn’t about what decisions Sharpton made. This is about a system that profits from racism.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the pleasures of outrage, about why viewers and media choose some kinds of outrage and not others. There are good kinds of outrage. Not only is there the kind of outrage that mobilizes people to do something about oppression, but there is the kind of outrage at finding core beliefs challenged. That’s a very unpleasant outrage. It enables change, it destabilizes ideology, it calls a person to rethink core beliefs. It sucks for ratings, since most people just change the channel. Dellums would have presented that kind of outrage.

Sharpton didn’t. Racists like Sharpton. They like being outraged about him because the media representation of him can fit him into racist narratives (Limbaugh still uses him to stoke racist outrage). They wouldn’t have liked being outraged by Dellums. So, Dellums didn’t get the coverage that Sharpton did; the leaders of the ELCA, PCUSA, and so on didn’t get the coverage that Falwell or Robertson did because the kind of outrage that reinforces in-group/out-group thinking is profitable. The kind of outrage that is the consequence of simplistic in-group/out-group thinking getting violated is not.

Racism is a systemic problem. And it’s profitable because demagoguery is profitable, and racist demagoguery is particularly profitable. Limbaugh’s demagogic racism has made him a millionaire.

We’re in a culture of demagoguery because it’s profitable. Both Trump and Chauvin should both be held accountable for what they’ve done. But holding them, as individuals, accountable won’t do anything to change the system in which they and people like them flourish.